1 July 2016

An iron skeleton winds along the corridor of the building that used to house the first public school in the kingdom of Italy, now the home of CAMERA – Centro Italiano per la Fotografia, in Turin: it holds the vast amount of material accumulated over twenty years of activity by Francesco Jodice (Naples, 1967), a photographer who has always been engaged in an investigation of the contemporary geopolitical scenario. We are talking about Panorama, the first major survey of the artist’s work, curated by Francesco Zanot and accompanied by a book of the same name brought out by Mousse Publishing. We met Jodice at his studio in Milan, where he lives, to ask him about the motivations behind the work of one of the most interesting and many-sided figures in recent Italian visual culture.

How does Panorama fit into the course of your career?

I don’t know what impression visitors to the exhibition will take away with them, but for me it has certainly been an opportunity to reflect on the strengths of my work, and above all on its weaknesses: to understand in what moments it has not been able to produce a critical mass with respect to contemporary history.

Francesco Jodice, Capri, The Diefenbach Chronicles, #003, 2013.

Do you find that over the years your research has brought you a greater clarity with regard to our history, or that on the contrary the situation has grown increasingly hard to decipher?

At present I am in a state of great perplexity: in the last two years I have devoted myself in a frantic and exhaustive way to the observation and portrayal of the end of the short century and Western culture. Exhibitions like Weird Tales, the film Atlante made for Palazzo Fortuny in Venice, the installation American Recordings and the project on which I’m working now, Sunset Boulevard, devoted to the Gold Rush of the late 19th century in America, are only apparently isolated works, in narrative and formal terms: in reality, they are chapters in a single story, an attempt to bring the situation in which we Westerners find ourselves at this moment into focus. In the days following the opening of Panorama, when for the first time I was able to look at my twenty years of work as a whole, I started to think I could investigate the social and cultural questions I find interesting without necessarily having to refer to a particular geographical region or precise moment in history—as I have done up to now.

Francesco Jodice, What We Want, Mazara, R14, 2000.

In the photographic tradition, the term documentary implies an awareness of his historical role on the part of the author: photography is a means of preserving the memory of a present state, in which the possibility of an imminent change can be glimpsed. Can you identify with this definition?

Photography, having since the eighties finally been included in art’s “box of toys,” has assumed a characteristic typical of longer-standing artistic languages: being at one and the same time what they have always been and what they become day by day. I’m thinking, for example, of photography in the Instagram generation, of its relationship with the cinema, of the use of the image in a self-promotional manner, with the selfie, and above all of computer graphics. Almost the whole of the videogame world, the most powerful of all the ones that make use of images, consists of the reconstruction of scenery: virtual reality, Oculus Rift. Photography, within the framework of such a hyperrealistic technology, is transformed to the point where it becomes anti-documentary. This allows more mindful photographers to act in accordance with a concertina effect: to keep well away from the documentary, or take the view camera and head for the fringes of the landscape with a spirit close to that of the fathers of Italian photography (from Felice Beato to Guido Guidi), presenting a faithful picture of reality. I think it is important to be able to conduct yourself with self-assurance and awareness: opening the concertina as wide as possible, moving freely between documentary and virtual reality, but doing it with the same skill which, as Garry Winogrand put it, we apply to every shift in the axis of the camera and therefore feeling that we have the ethical responsibility to ensure that every picture we take produces meaning.

Francesco Jodice, What We Want, Tokyo, T03, 1999.

Your work was born and has developed, partly for obvious family reasons, in the realm of the visual arts. While many push to get their work accepted within the art system, you row in the opposite direction, taking it outside its boundaries. I am thinking of your experience at the São Paulo Biennial in 2010 where, to counter the exclusivity of the previews for VIPs, you decided to anticipate the opening of Citytellers by having it broadcast on TV.

Precisely because of my family background, I have a childhood memory, not so much of what art was, which I didn’t understand and wasn’t interested in, but of how it was done: people getting together at somebody’s house, with someone taking his clothes off and starting to write on his body, someone else standing up to recite poetry, or filming a young man in the street because he found him beautiful. There was something compulsive and even a bit naïve about it, but there was above all the idea, a very natural one, that art was one of the things you do in life. Everywhere and always. The example of the Biennial is very important, because it stems from a lesson that I learned from my observations of those years: that art, a very rigid and orderly system nowadays, has to find a form of freedom. Whence my attempt to take it exactly where it does not seem to be well accepted: it is a mistake to think that mass culture is not ready to welcome it. Finding mechanisms to break down this system, distancing myself from this kind of elitism, is the most interesting part of my research. Putting the film São Paulo on TV, writing a book of fiction like American Recordings, organizing a drive-in at which people eat sausages, these are ways of implementing this process of breaking down barriers. If this process were to mean that not all the figures in the art world would survive, it’s not a problem. There are too many of us anyway.

Francesco Jodice, What We Want, Phi Phi Ley, R18, 2003.

For many years you’ve been teaching at the academies and training young people in your studio. Have you ever thought about devoting yourself to exclusively curatorial projects?

I think that teaching and curating are very different practices, at least as different as teaching and being an artist. Teaching for me means on the one hand exorcizing a sense of guilt over the advantage I know that I have had with respect to my generation, an unbridgeable gap for those who come from families in which their parents did something completely different: my education was identical to the Karate Kid’s, a continuous and priceless exercise of vision. On the other, being in a class with students means being paid to steal from them the vocabulary of today. An important opportunity for those who, like me, are afraid of being left behind and not understanding certain needs, patterns of consumption and cultural mechanisms, mostly linked to new technologies. Curating is a very complicated affair, greatly undervalued in Italy. The way I see it, the curator ought to know everything about art, in the past and in the present: everything that has been written and has been done, everything that is being written and being done today. He has to be informed about any new cultural phenomenon that is emerging around the world, whether it is in Malaysia or Peru. In short, the critic-curator has to be a sort of Superman! This unquestionably conflicts with my laziness. My culture, moreover, is circumscribed, precise, not generic: I like to know everything about something small, on the sidelines, generally useless too. Art on the other hand, in contrast to the American horror movies of the seventies, cannot by nature be circumscribed, it has to talk about all aspects of life. So no, curating doesn’t interest me. I don’t believe that curator-artists exist. There are, however, many very good artist-curators: they are generally South American, from Eastern Europe, Albanian. This happens because they come from contexts in which, in the absence of a system, it becomes necessary to construct for themselves the cultural habitat in which to exhibit.

Francesco Jodice, What We Want, Aral, T51, 2008.

A do-it-yourself art system, fruit of an absence and an urgent need. At what point are we in Italy?

The equivalent of what I’m describing, in Italy, happens in independent publishing. After my and Armin Linke’s generation, for economic as well as cultural reasons, this country has no longer had the possibility, or the capacity, to support photographers. As a consequence an entire recent generation of excellent artists—like Mirko Smerdel, Alessandro Sambini and The Cool Couple—has not found a system to back them. On the one hand they rejected the strictly photographic context, on the other the art system gave them the cold shower, because, from the collector’s viewpoint, the market value of photography has always been too low. So they have made their own system. Extraordinary publishers have emerged in the photographic sector in Italy: Discipula, blisterZine, Humboldt Books and so on. If it were just a couple of them, this might just have been by chance, but when there are twenty, of the highest quality, then it has to be seen as a phenomenon. Which has not arisen because suddenly someone had a desire to publish books, but because there was a more less conscious need to give exposure to all this new artistic production. In those cases, what has happened is a union of production and curating: Mirko Smerdel is an example of a perfect balance between excellence as an artist and excellence as a publisher, one who makes choices and is therefore also a critic and a curator.

Francesco Jodice, Ritratti di classe, Torino, #002, 2005.

Talking of curating, on the occasion of Panorama you literally put your work in the hands of Francesco Zanot, an act of faith that follows on from a longstanding synergy. How did you cooperate on the exhibition?

Despite having had the fortune to work in the past with important foreign professionals—Okwui Enwezor, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Lisette Lagnado and many others—I’m not very good with curators, because unfortunately I’m not very willing to let other people play around with my work. With Francesco Zanot it was different. Although we are old friends, it was the first time we had worked together. On the one hand, he did very well to go in studs first, expressing the idea he had of my work, and thus imposing a modus operandi. On the other, perhaps simply out of a desire to bring the chapter of the 20th anniversary to a close, it was as if I wanted, for the first time, to arrive in a place where a surprise party has been thrown for you. And so, within certain limits, both the exhibition and the book are the product of Francesco’s work.

How was Panorama conceived in spatial terms?

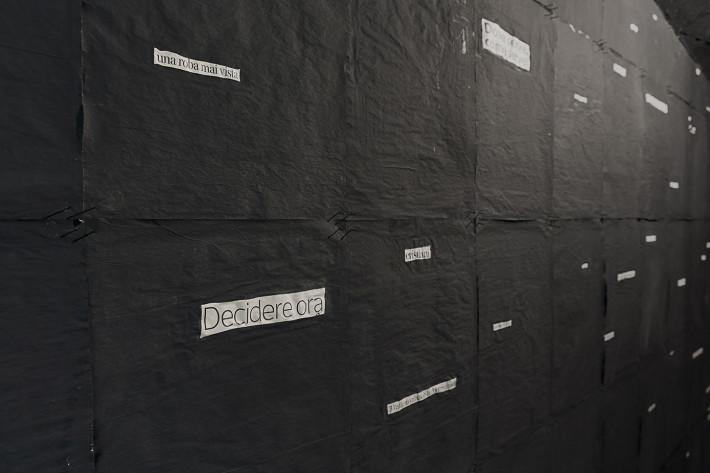

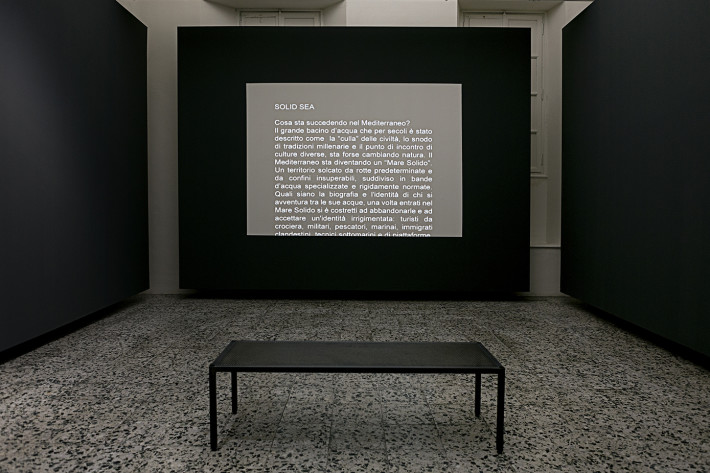

The space at CAMERA is very beautiful and prestigious, but physically difficult to deal with, as it is rigid: six rooms in a row, a corridor. We decided from the outset to work in such a way that the space would give form to the exhibition. In the rooms there are projects presented in a sacred and hieratic manner, to be observed without interaction: they are the finished works, in their maximum formal expression. In the first room, for example, the only photographic work from the What We Want project is the large picture of Hong Kong, set about 25 centimeters above the point of view considered correct for a photograph of those dimensions, precisely to create an effect of grandeur. The rooms impose a respectful attitude, typical of the work of art. In the corridor, by contrast, everything gets dirty. The table designed by the architect Roberto Murgia, 50 centimeters wide and almost 50 meters long, continually changes wavelength: seat, table, counter, door and arch. Here you can touch proofs, listen to pieces of music, browse through books, look at film filters, read texts and much more. This was the fundamental idea: an exhibition in which the work of art, the study, the process and the method were equivalent. The book acts in the same way: the works rest on the graphic base, while the methodological part is hung from the upper edge of the paging grid. In some cases, fragments of the process are even more beautiful than the finished works.

Francesco Jodice, La notte del drive in. Milano Spara, 001, 2013.

Dedication, attention, comprehension: these are indispensable terms for anyone approaching your work. The viewer is asked to make an effort, to such an extent that you have calculated a visit would have to last about 24 hours in order to appreciate the exhibition fully. In an exercise so focused on research and study, what is your idea of beauty and at what stage of the work is it revealed?

Over a century after its publication, I remain a firm believer in the theory put forward by Adolf Loos in Ornament and Crime, that beauty is the natural consequence of the production of meaning. And while we’re in the realm of quotations, I believe just as strongly in the Latin aphorism mens sana in corpore sano, but turned on its head: the body is healthy and beautiful when the mind is healthy. Intellectual nourishment produces beauty, otherwise we will all end up like Chiara Ferragni. Art produces beauty almost as a sort of by-product, a side effect. The artist is not a product designer, a graphic designer, a decorator. To explain what the real meaning of artistic practice is for me I often cite the example of the work of Santiago Sierra in which, using the municipality’s money, the artist gets some illegal immigrants to hire trucks, use them to block expressways and then run away (Obstrucción de una vía con un contenedor de carga, 1998, interviewer’s note). Maybe someone dies, because he had to do a hemodialysis and found the road blocked. Art is not concerned with bringing about improvements in society, that is the job of politics, or with producing predictable beauty—for that there are the architects of parks and gardens. Art produces chaos, and chaos serves to make us ask why things are the way they are. One of the consequences of this chaos, the only true purpose of art, is beauty. As Gaston Bachelard said, the point is not to recognize things, but to look at them all as if it were for the first time.

Francesco Jodice, Cartoline dagli altri spazi, #002, 1996.

Right from your earliest work, Postcards from Other Spaces (Cartoline dagli altri spazi), you have been interested in collective living, with a growing presence of the human figure portrayed in its individuality. How does the identity of the individual relate to the attempt to observe the contemporary landscape in its communal dimension?

My projects stem from an analytical, lucid and not very emotional attitude. Studying photography, I was struck by the afterword of Viaggio in Italia (ed. by Luigi Ghirri; Alessandria: Il Quadrante, 1984, interviewer’s note), where the disappearance of the figure was justified by the need to no longer tell stories through people, but through the things that belong to them. That period arrived at the end of Neorealism, when the human presence had been taken to an excessive level. When I started to work, in the late nineties, after studying architecture at university, I had the distinct impression that the Italian landscape was physically immobile. In contrast, the human landscape was beginning to change. Not having a history of colonialism, it was the first time that we began to see foreigners, for example. The referendums on abortion and divorce, promoted and won by the Radical Party when I was still a child, had changed the shape of the Italian family forever. So I felt the need to reinsert the human figure in the landscape and I set about the task in a precise way, constructing a ratio of 1:1: one figure, one scene. The same approach can be found in Postcards from Other Spaces, Temporary Habits (Abitudini temporanee) and the Prado project. What matters in these projects is the accumulation, the serial character, the densification. Each constructs a repeated photographic monotype, where scene and figure are the variants. The system of relationship changes often: in Postcards from Other Spaces the figure is small, although it has a strong influence on the urban setting; in Temporary Habits everything is inverted and the image becomes vertical, while the heights change in relation to the “anthropometric” process of my photography (as Lea Vergine has defined it): the figure becomes so important that it deforms the picture. In Class Portraits (Ritratti di classe), where I reworked the traditional school picture that was taken by the local photographer, this aspect has begun to include the multitude, but the principle is the same: the physiognomy becomes so preponderant that the background is limited to a few bits of landscape. The city is only glimpsed between figure and figure.

Francesco Jodice, Mont Blanc, Just things, #004, 2014.

On another occasion, speaking of the exhibition Primo lavoro, you explained that the satellite image, inasmuch as it is automated, creates an immediate sense of authoritativeness. Is it an effect that you seek in your photographs?

Taking two extremes, we can imagine that the maximum distance between two photographs is the following: on the one hand the satellite, a technological eye in the sky that produces images in a scientific or random manner; at the other extreme, the vernacular picture, taken by a parent on his child’s birthday. The first disregards any occasion: not only is it anti-celebratory, but to all intents and purposes it is dehumanizing, as it excludes any previous cultural system or apparatus. In contrast, the photograph of a party is not just driven by the emotions of the moment, but also by the images of birthdays seen, experienced, rhetorically reproduced in a movie… Mine is a slightly different undertaking: on the one hand, I try with my work to speak of things through the construction of a filter that rejects an emotional participation in life—unlike the reportage of Salgado, McCurry, Cartier-Bresson and Capa which is, just to make things clear, closely linked to feeling. At the same time, my photography does not lack a cultural filter, but that filter only sifts the shared and relevant rhetorical elements. Shared, because they are no longer part of a private celebration, but of one in which all of us have participated collectively. Relevant, because I try to extract those parts that may have significance in the near future. I distance myself both from the emotionalism of the family context and from the absence of any knowledge of culture. This is the photographic code I attempt to produce.

Having worked on geographical differences all over the world, to what extent can your works be considered site-specific, and thus generated by the reality that you are observing?

The attention I pay to geography and geopolitics, in reality, is a consequence of my interest in another aspect of life: the near future. I am intrigued by what is about to happen, what paradoxically has already happened: the emergence of a new phenomenon in culture is the aftereffect of something that we have, more less consciously, premeditated. The future is always the consequence of something that we have planned in a confused way in the recent past: this is why I always work in places where I believe something sensational is about to happen. The geographical areas in which I move are relevant, but they are also used as an excuse: Citytellers comprises three films, shot in Dubai, Aral and São Paulo respectively, because I wanted to talk about self-organization, the disappearance of the great idealistic movements of the 20th century (communism, in Aral) and our new willingness to accept a form of slavery. I could have made them in other places too, but these three seemed to me to offer a clear and simple view of a specific phenomenon: the imminent future that was already present in the most recent past. The truth, and this is what What We Want with its 150 places demonstrates, is that the individual place and the individual phenomenon are of very little interest to me. What does interest me is to know what happens when hundreds of new patterns of behavior start to conflict: if you observe this rat-tat-tat, this progressive adjustment, you get a panoptic idea of reality. In this respect, I have been influenced by the title of an imaginary treatise written by an imaginary geologist, the protagonist of Peter Handke’s Slow Homecoming who loses his memory and writes a paper on comparative studies of similar phenomena in different parts of the world.

In conclusion, after global and geopolitical situations, a question on your private geography. Why have you never left Italy?

The principle by which I connect up the way I live and the way I work is the same as that of a hikikomori: I live shut up inside a fortress of things that give me pleasure and satisfaction, with a genuine feeling of hostility toward the community in which I live. I like to think of myself as an alien anthropologist who, observing human beings on earth, asks himself: “But what is he doing that old man, dressed in white, with a little hat on his head and silk shoes, pontificating on everyone’s life despite having no experience of it?” I don’t believe that today you have to be in New York, Tokyo or London to understand what is going on in Malaysia; on the contrary, you run the risk of becoming terribly provincial. It is quite possible, instead, to work like Salgari, staying in one place and using everything that the internet and journalism has to offer in order to have an excellent panoptical vision. What matters is to make sure that the stronghold we construct is in perfect atmospheric conditions: everything should be clear. A place where the observatory has a 360-degree view.