14 June 2016

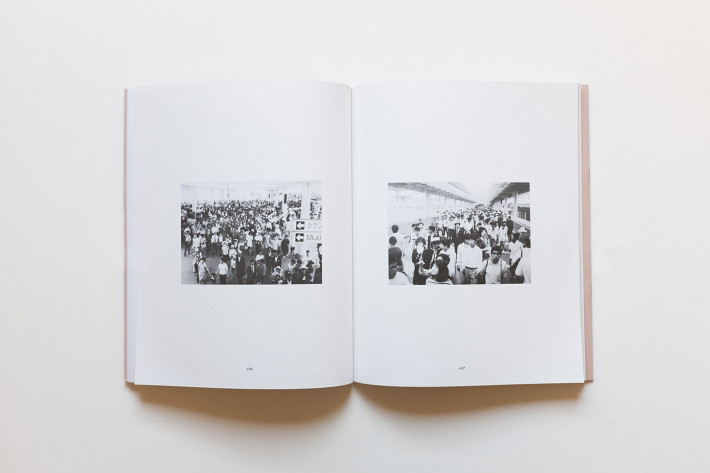

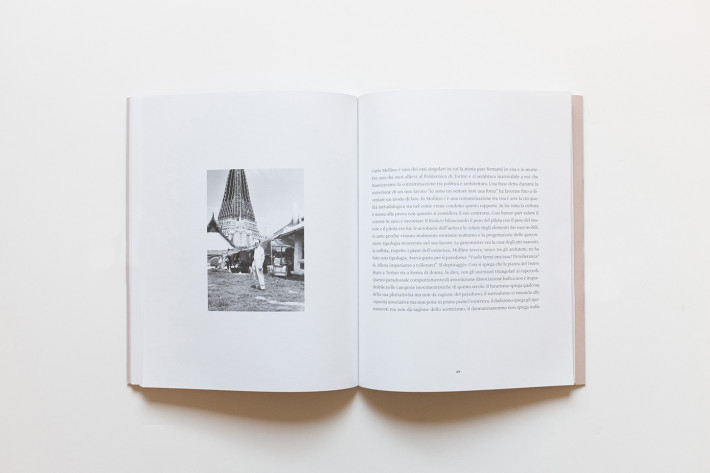

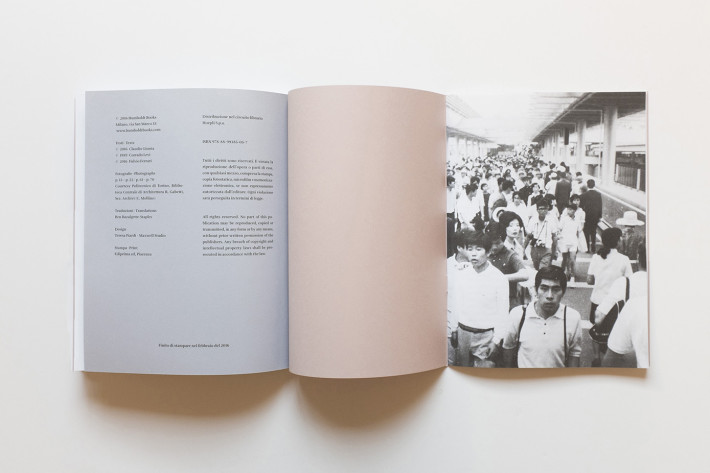

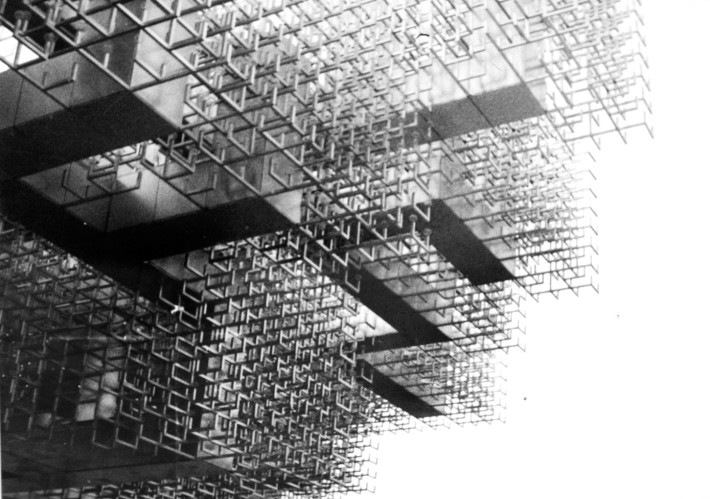

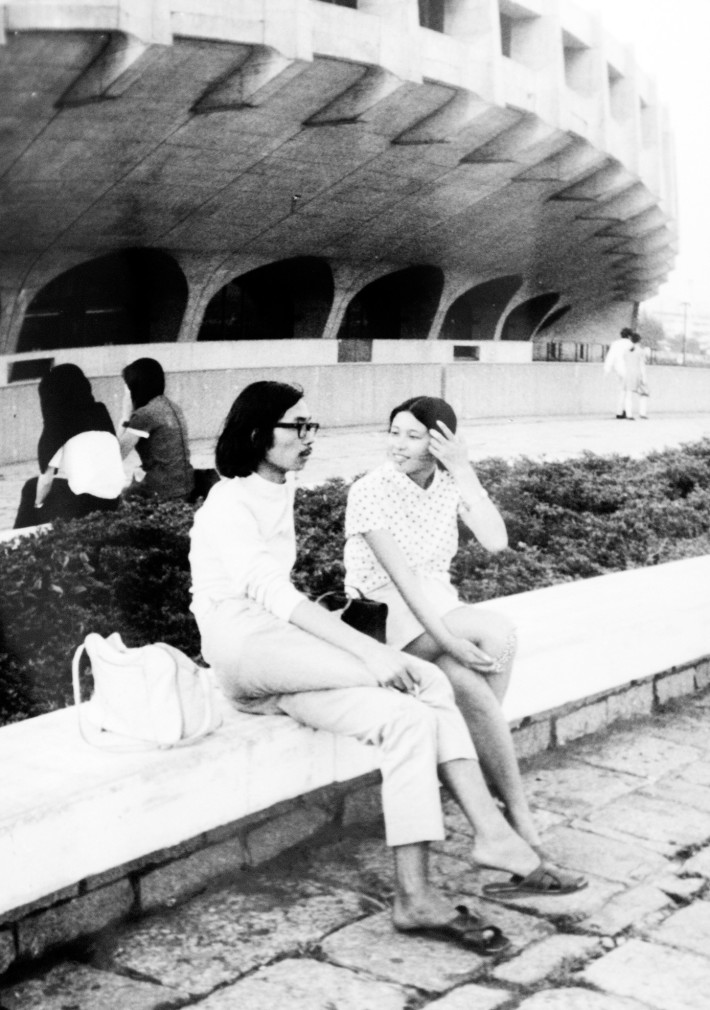

Armed with a Leica and a Polaroid, Carlo Mollino—at the age of sixty-five, three years prior to his death—boarded an Alitalia DC-8 on May 21, 1970, and flew to the East. His destination (after stops in Athens, Karachi and Bangkok) was Japan, and in particular Osaka, where the Expo was being held. Obviously this offered him a pretext to travel to and explore a culture with which a host of other architects and designers have fallen in love, from Christopher Dresser—one of the first to visit the country in the modern era, in 1876—to Carlo Scarpa. Carlo Mollino, Giappone 1970, published by Humboldt Books, presents this encounter to us through the pictures that the architect took in the two weeks he spent away from Turin. At its center, therefore, is his photography, but from an unusual point of view: outside his pictures of dreamlike boudoirs, with no demoiselles (to tell the truth there are a few, but with their clothes on) and with none of the skiing acrobatics that he liked to portray on the Alpine peaks. It starts with a shot snatched from the cabin of the plane and continues with ordinary people, photographed alone (and often embarrassed by Mollino’s voyeurism), in couples or as a teeming mass. Then come details of buildings, typical Zen landscapes and the nondescript scenery of the Japanese megalopolis, but we also find a lady in a kimono with the inevitable cup of tea. It is not a systematic piece of reportage. There are no exceptional shots, nor unforgettable moments. “It is a detached man who is composing them,” writes Fulvio Ferrari in one of the accompanying texts (the others are by Claudio Giunta and Corrado Levi, this last written in 1989): for example, in the photo taken from the plane we find a geometric construction that reflects the eye of the architect and the dynamism of Futurism, with its foreshortened view of wings, turbines and fuselage. The layout of the book, with one black-and-white picture on each page, creates some telling juxtapositions: the metal megastructure designed by Kenzo Tange to house the Expo is coupled with a detail of traditional Japanese roofs, revealing the continuity and the friction in the dialogue between modernity and tradition. Another building designed by Tange is St. Mary’s Cathedral in Tokyo, a strange creature emerging from the ground that Mollino, entranced by the sinuosity of its white curves, photographed from several angles. An appendix adds other Oriental locations that Mollino visited during his lifetime, in particular four photos of Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh. The volume closes with a self-portrait of the Turinese designer in front of an Indian temple: the framing is slightly askew and the solidity of the monument, intact for centuries, almost seems to tend toward a giddy rotation, while a smile plays over his sharp-featured and mustachioed face. It is tempting to investigate this link of Mollino’s with Japan a bit further. For in the glittering dark of his bedrooms, among collections of butterflies and allusions to the baroque, surrealistic images and bare buttocks, we can also find the echo of a Japonisme interpreted in various ways, ranging from Hokusai to the fantasies of Henry van de Velde and passing through a thousand other places before arriving in the end in Turin, after having traveled along the mysterious ways of art.