22 May 2019

Pandemic

A tragic epilogue that became an epic prologue. The Nazis, by forcing the Bauhaus—the celebrated school of art, design and architecture founded in Weimar in 1919—to close its doors in 1933, triggered a dramatic diaspora, but one that proved incredibly fruitful for all the countries that had the fortune to take in the migrants. They wanted to halt the contagion but, as it turned out, did nothing but foster an unstoppable pandemic, whose effects can still be felt today, a hundred years after its outbreak. The best-known case is that of the United States, which welcomed a considerable number of Bauhäusler with open arms, including the school’s most famous teachers: Walter Gropius (founder of the myth) at Harvard, Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Josef and Anni Albers at the Black Mountain College, Moholy-Nagy at the New Bauhaus Chicago, etc. It was they who sowed—each in his own way—the seeds of the German experience on the other side of the Atlantic, influencing the new generations of designers. It suffices to think of a few who were destined to become household names, like Paul Rudolph or I.M. Pei, students of Gropius; or the many followers of Mies, from Philip Johnson, a very special pupil, onward. The consecration of the American myth of the Bauhaus came with a sacred ceremony, held in a New York cathedral: in 1938 the Museum of Modern Art staged a major exhibition—with the display and catalogue designed by Herbert Bayer1—that became its New Testament.

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building in Dessau, 1925-26, view from south. Photo: © Tadashi Okochi, Pen Magazine, 2010, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau.

In the rest of the world, however, the Word was spread in a much broader and more diversified manner, as is evident from the many exhibitions that are being put on to mark the centenary (1919-2019). The one at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, running until May 26, 2019, illustrates for example the relations between the Netherlands and the Bauhaus, from the origins until the arrival of around thirty of the school’s former students and teachers who sought refuge in the country after 1933, working for Dutch industries, opening professional practices and teaching.2 Much less well-known though is the echo of the Bauhaus on other continents, something which has been brought to light at last through a research project carried out by Marion von Osten and Grant Watson, Bauhaus Imaginista, which after many preliminary stages around the world is being summed up to mark the centenary at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin (until June 10, 2019).3 The exhibition uncovers little-known and often unexpected connections and contacts that are leading to a shift in geographic and historical perspectives on the Bauhaus. At the center of the exhibition are the many pedagogical experiments that can be considered in various ways akin to (or inspired by) that of Gropius and his colleagues. Interesting, for example, is the parallel between the early Bauhaus and the Kala Bhavan school of art near Calcutta, founded the same year (1919) by the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, who was trying to find a postcolonial road for local design through a mixture of Eastern traditions (from India to Java), the avant-garde and the British Arts & Crafts movement. The result was a sort of “rural modernism,” linked to the context but open to international influences.

The experience of the Bauhaus, and above all the approach to teaching of Johannes Itten, had affinities with that of the Indian school. The Austrian art historian Stella Kramrisch realized this: called on to teach at Kala Bhavan, she wrote to Itten about organizing an exhibition on the Bauhaus in Calcutta, which was held in 1922 at the 14th Annual Exhibition of the Indian Society of Oriental Art. It was the first exhibition on the German school outside Germany; the first step in the building of its international reputation.4 The exhibition in Berlin is lavish with its connections: they range from Nigeria to Taiwan, from North Korea to China, from Mexico to the United States, from Brazil to Morocco, from Russia to Japan. In many countries, this radical overhaul of teaching represented an antidote to the academicism, often of colonial origin, that had held sway up until that moment, which contrasted with the freshness of local traditions. In this sense, the Bauhaus functioned, as in the case of the Research Institute for Life Design in Tokyo, founded in 1931, as a platform of cultural exchange in which the academic hierarchy between fine art and the applied arts was discarded. Art, stripped of the hoarier side of its sanctity, became something that could be used to improve people’s everyday life, reflecting the impulses—unfortunately soon disappointed—toward the democratization of society. It is important to stress that the exhibition has carefully avoided celebration of the Bauhaus as the sole driver and model of the many stories told. The complexity of the individual voices tends instead to create a network free (or almost) of hierarchies, bringing out the specific enrichment generated in each chapter.

Alfred Schäfter (design and production), suspension lamp, prototype, 1931-32. Photo: © Gunter Binsack, 2018, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau.

Myth and Rejection

So we can speak of many Bauhauses, not just one. Several Bauhauses coexisted and alternated while the school was in operation, but many more—official or unofficial, connected or parallel—constituted its posthumous legacy, in a process of exploitation that represents as interesting a critical problem as the actual influence of the “original” one. The evolution of the post-Bauhaus period in the United States, to which reference has already been made, epitomizes the multiplicity of voices that carved up its heritage. To give just one example: the aforementioned exhibition at the MoMA in 1938 only covered the period when it was run by Walter Gropius (1919-28), excluding the times when Hannes Meyer and Mies were directors of the school and marking the beginning of a process of historiographical “censorship.”5 In Italy, after the Second World War, we can find the contrasting visions presented by Bruno Zevi and Giulio Carlo Argan. For the former, the German school was in fact “the opposite pole to Le Corbusier’s dogmatism and almost a settling chamber for the evolution from rationalism into ‘organic tendency.’”6 While for Argan, whose fabled monograph was published by Einaudi in 1951,7 the figure of Gropius (viewed as synonymous with the Bauhaus) was a symbol of the necessity of a social and political role for the architect. Everyone had his own axe to grind and the Bauhaus became a mirror in which to gaze at one’s own reflection, perhaps adjusting the angle to accentuate the most suitable side.

In short, the Bauhaus—like so many other cultural phenomena—has been idolized in various ways in relation to a particular interpretation or ideology, with disruptive effects. Reyner Banham, who had already drawn attention to the contradictions of the school in his Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (1960),8 reflected this aspect. In a talk entitled “The Bauhaus Gospel” given on British radio and published in The Listener in 1968,9 Banham discussed the popularity of the school in the media, starting out from his first encounter with Moholy-Nagy’s book The New Vision (1939).10 Deploying his acute sarcasm, the British critic wrote: “I won’t say that it was a deconversion on the road to Damascus, but there was a strong sense of having held in my hand a sacred text, the Third Testament, the gospel according to the Bauhaus.”11 Banham stressed how books of this kind, characterized by an incisive presentation of concepts and related images, made a great impression in Britain: “Bauhaus books like Moholy’s or Paul Klee’s […] must have appeared marvellously solid and convincing […]. Art-school eggheads clung to them like life-belts.”12 If Gropius, as is well known,13 was unable to put into effect his plan to found a new Bauhaus in Britain, its influence arrived there through publications, rather than through direct contact with the exponents of the school. “Books, books, always the printed word. It really did become like the word of God, because art-school reformers seemed to believe that within those books there was revealed a system of education eternally and universally true. Instructors, it seemed, were to reduce themselves to the status of humble vessels of the Word […].”14

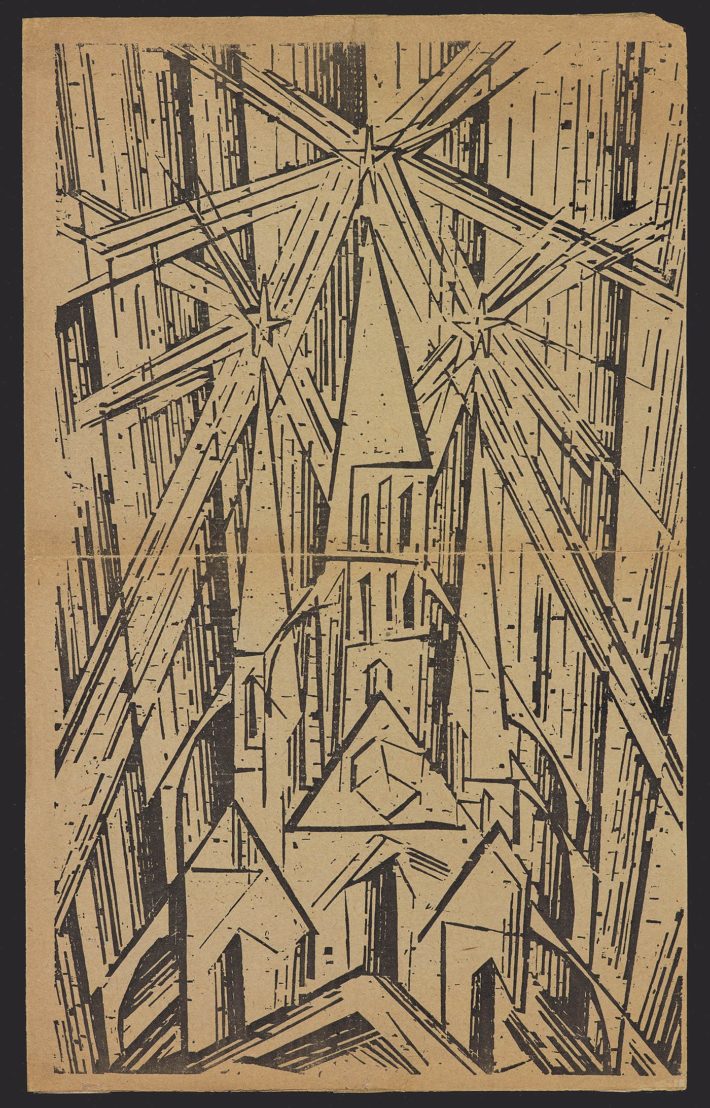

Walter Gropius (author) and Lyonel Feininger (cover design), Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar, April 1919, woodcut. Private collection, the Netherlands.

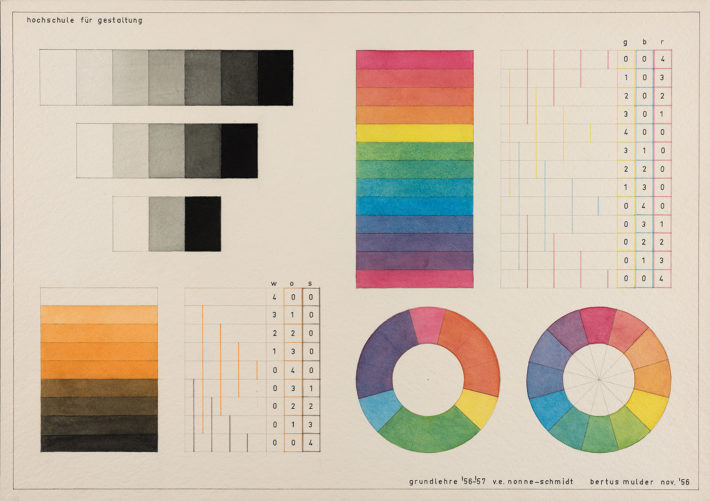

As in a holy war, the interpretation of the Holy Scriptures—or the actual works—of the Bauhaus led to fierce conflicts. Some of the harshest were the ones that arose at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm (1953-68), a school initially directed by Max Bill. A former student at the Bauhaus, he resigned in 1956 precisely because of internal clashes, in particular with Tomás Maldonado, who had a totally different educational program in mind.15 Bill was also attacked by the Danish painter Asger Jorn, promoter of the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus (IMIB),16 which included members of the Movimento Nucleare (Enrico Baj, Sergio Dangelo) and former members of the CoBrA group. For Jorn, Bill’s interpretation was totally unsound, as it was too concerned with technique at the expense of creativity and the imagination.17 The exploitation has not only been in a positive sense or in search of a lost virginity. In the view of some, the Bauhaus had in fact become a scapegoat for all the ills of the century. Such as Tom Wolfe, who chose the German school as the target of his short but popular book entitled From Bauhaus to Our House (1981).18 According to Wolfe, America had been invaded by European intellectual colonialism, embodied by the “Silver Prince” (Walter Gropius) and the other “Whites,” leading to a generalized lowering of the quality of building. “The terms glass box and repetitious, first uttered as terms of opprobrium, became badges of honor. Mies had many American imitators […]. For a hierophant of the compound, confidence came easy. What did it matter if they said you were imitating Gropius, Mies or Corbu or any of the rest? It was like accusing a Christian of imitating Jesus Christ.”19

It is worth mentioning the much more refined reworking of the iconography of the Bauhaus by Alessandro Mendini, who in the seventies chose it as the epitome—perfect from the communicative viewpoint, given its fame—of a functionalist approach that needed to be overcome with a view to the liberation of the figure of designer as artist.20 In 1975, Mendini, engaged in the production of “objects for spiritual use,” created a significant installation entitled Lamp without Light, consisting of a series of table lamps by Marianne Brandt and Hin Bredendieck thrown into a puddle and deprived of their raison d’être: the light bulb. By removing the product’s most functional attribute, the light bulb, from the lamp, Mendini was proclaiming his opposition to the diktat of “form follows function,” one of the slogans foisted on the Bauhaus.21 Three years later, with his operation of “redesign of designer furniture,” Mendini took Marcel Breuer’s famous Wassily chair and decorated it with colorful post-Futurist forms: another apparent piece of mockery that was in reality a return to the artistic freedom of the school’s “Expressionist” phase.

More colorful still was the interpretation of the Bauhaus by the prophet of Brazilian architecture, Oscar Niemeyer, who never concealed his aversion for the school. In an interview granted to the newspaper Correio Braziliense in 2008, he called the Bauhaus “the most moronic group there has even been” because it took no interest in the form of things. “The head of the school, Walter Gropius, was an asshole. He came to my home at Canoas [the magnificent glass house with a sinuous profile, immersed in vegetation, that he had designed at the beginning of the fifties in Rio de Janeiro, author’s note] and said the biggest crock of shit I’d ever heard: ‘Your house is beautiful but it is not multipliable’. Quite right, son of a bitch! To be multipliable it would have to be on a flat piece of ground, I would have to look for the same scheme and my aim was not a multiplying house, but a good home to live in. They were like that, with no light. The work that the Bauhaus has left behind consists of a load of houses that repeat themselves. It was a moment that threatened architecture, but Le Corbusier and the others reacted against it. It was a period in which stupidity wanted to make its way into architecture, but it was stifled.”22

Marianne Brandt and Hin Bredendieck, 679 GV, 1928, cast iron, brass, iron. De Groot collection.

The historical reinterpretation of the Bauhaus in Germany after the war was more complex, as it touched some raw nerves, linked initially to the school’s opposition to Nazism and later to the relationship with the dominant ideology on one side and the other of the Wall. In the East, above all, the history of the school was often branded as a bourgeois phenomenon, not worthy of particular recognition. And in fact the houses of the teachers at the Bauhaus in Dessau were left unceremoniously to deteriorate. In particular, the Gropius Haus, an emblem of modernity in the twenties and then damaged by bombs during the war, was even replaced by a nondescript little house with a pitched roof. This remained standing until recently, when the decision was taken to demolish it and construct in its place a sort of simulacrum inspired by the original building, which was inaugurated in May 2014.23 Quite apart from its actual architectural quality, the design of this “avatar,” by the Berlin-based practice Bruno Fioretti Marquez (two Italians and an Argentinian), raised numerous questions with respect to the criteria for the selection, removal and reconstruction of such a historic building. However drab, the house constructed in the Soviet era on the foundations of the Gropius Haus in fact represented, in its pettiness, the most concrete and tangible sign of the violence of the war and the subsequent damnatio memoriae inflicted on the traces of the Bauhaus. In the West, on the other hand, the postwar period saw a sort of mythicizing of the school, and in parallel a critique of such idealization. “Here a cult has arisen,” wrote the former student Waldemar Alder to Hannes Meyer in 1947, “as if the Bauhäusler belonged to a special category of people with particular artistic abilities and high moral standards. But it is not so.”24 The criticism would grow harsher in the years of the GDR.25 On both sides of the Wall or the Atlantic, in short, the Bauhaus has been utilized as a standard or a scapegoat, seen as a model or an enemy, in a seesawing ideological and historiographical evaluation.

The Bauhaus Today

Considering the way the Bauhaus has been treated as a critical problem inseparable from that of its historical reconstruction,26 the centenary provides an opportunity to take stock of a phenomenon that is now viewed in a historical perspective, but is at the same time undergoing continual revision. On the one hand the Bauhaus, seen as a national historical heritage in Germany (as are its resurrections in the United States), has found in the anniversary a megaphone for its amplification in the media and the renewal of its fame, thanks to an extraordinary allocation of funds, unimaginable under other circumstances, that has led to some ambitious initiatives. How many other countries have thought, in recent years, of building a total of three new museums at the same moment, all devoted to the same subject? In fact Weimar has seen the opening of a new Bauhaus Museum and the museum in Dessau will soon be completed, while work continues on the expansion of the Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin. Designed by Gropius, the latter will be renovated in its entirety by the architect Volker Staab. Only in the coming years will we able to assess the way in which the collections housed in these containers are going to be displayed and explored.

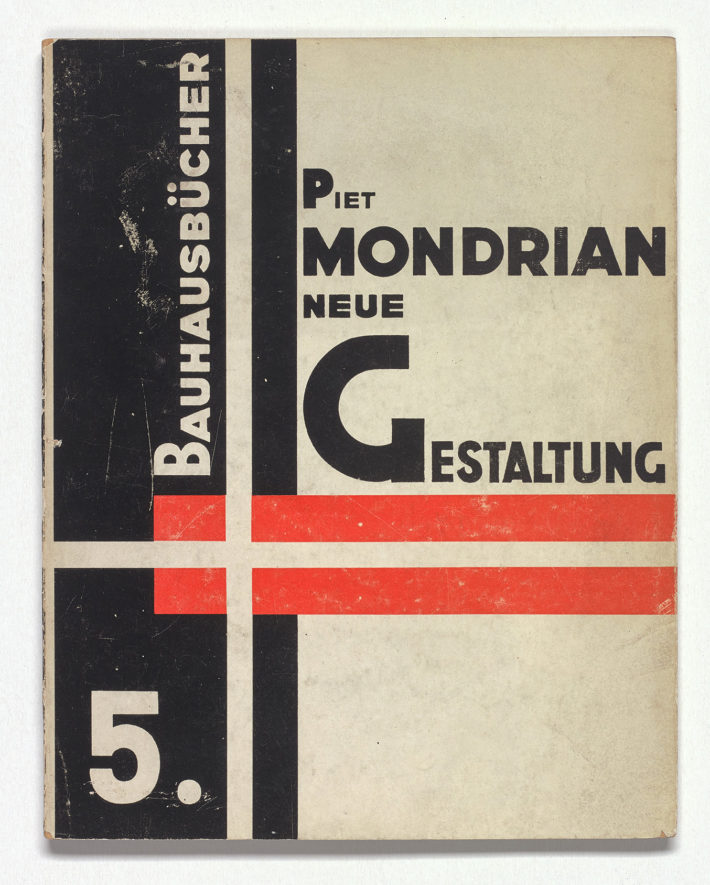

Piet Mondrian, Neue Gestaltung (no. 5 of the Bauhausbücher series), design László Moholy-Nagy, 1925. Private collection, the Netherlands.

On the other hand, as the exhibition Bauhaus Imaginista demonstrates, the most recent research has been able to open up new historical interpretations, in which celebration has given way to a ramification of the legacy, of the mutual influences, of the contaminations. As well as to the uncovering of less well-known contributions, commencing with the female one:27 there are a large number of women linked with history of the Bauhaus in one way or another who have finally found visibility with this centenary. From this perspective, the Bauhaus becomes a means for the interpretation—fundamental but not limiting and not exhaustive—of the complexity of the evolution of models of teaching in the 20th century. In this case the Bauhaus is not so much a mirror as a filter, able to broaden and sharpen the vision instead of just reflecting a theoretical image. What remains unsettled, or rather in continual development, is what we might call the “practical legacy” of the Bauhaus, i.e. the extent to which the example of the school is still a source of inspiration for the graphic and product designers as well as the architects and artists of our own day. The exhibition Bauhaus Imaginista has tried to come up with an answer to this too, by asking a number of artists to create works “inspired” by the activity of the Bauhäusler. Many other designers, in recent years, have reflected on this in more or less concrete terms, declaring a direct link with the German school. The most interesting and telling examples seem to be the ones who have chosen to take up not so much the forms of the Bauhaus as the idea of a design capable of influencing society. Van Bo Le-Mentzel, a German architect of Laotian origin, has attracted the public’s attention with a collection of do-it-yourself furniture, Hartz-IV-Möbel, that draws on the iconic character of some pieces by Marcel Breuer and others.28 The idea, in reality closer to Enzo Mari’s self-design29 than to the Bauhaus, has stimulated other performances and initiatives, including some in collaboration with the Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin. The Bauhaus Campus Berlin, set up in 2017-18 in the shadow of the museum, served for example as a physical and conceptual platform for the creation of a series of “Tiny Houses”: small mobile units inspired by the research into housing carried out in the Weimar Republic, but with a function updated to meet present-day needs, such as the accommodation of refugees.

On the other hand, we have been witnessing for some time a process of trivialization—something clearly analyzed by Annemarie Jaeggi, director of the Bauhaus Archiv in Berlin30—that exploits in various ways the media potential of the brand invented by Walter Gropius a hundred years ago. Leaving aside the dozens of cases in which the name of the Bauhaus has been used for initiatives that have nothing to do with design or architecture (toys, commercial enterprises of every kind, do-it-yourself stores, etc.), there have been numerous others within these fields in which it has served as mere window dressing. The list of furniture and houses “in the Bauhaus style” would be a very long one, so we will cite just one of the most recent examples: that of the Walter & Wassily sunglasses (sold under the Neubau Eyewear brand), brought out to coincide with the centenary. The words used to explain the link with the two protagonists of the Bauhaus (Gropius and Kandinsky) are filled with clichés and banalities, but work perfectly as a bait: “The high-end sunglasses are also a creative take on their ethos that ‘form follows function’. For our Walter & Wassily campaign shoot, we reinterpreted the legendary Bauhaus credo and, adopting the motto ‘human follows form’, we’ve shown how design and people can be staged as an innovative duo. While interior design and architecture have long been celebrated as the primary disciplines of good taste, we have strived to make sunglasses—our everyday companions—an impressive design object.” Mirror, decoy, filter, sunglasses, blinkers or telescope to probe new horizons, the Bauhaus will remain a myth for a long time to come.

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building in Dessau, 1925-26, view from south. Photo: © Tadashi Okochi, Pen Magazine, 2010, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau.

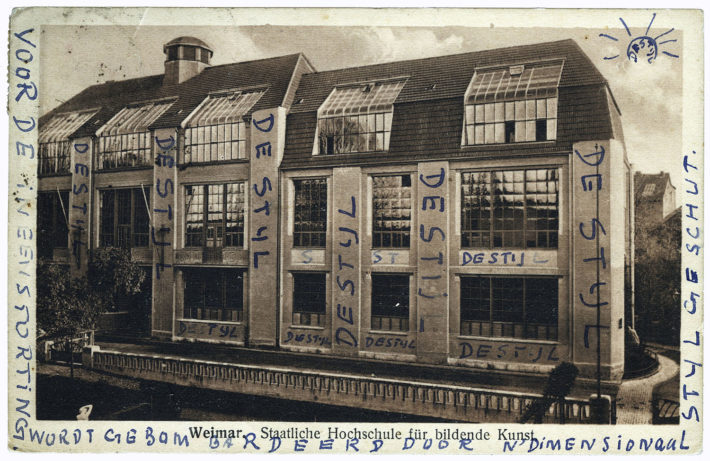

Postcard with a picture of the Bauhaus in Weimar, written by Theo van Doesburg and sent to his friend Antony Kok, September 21, 1921. RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague (Archive of Theo and Nelly van Doesburg).

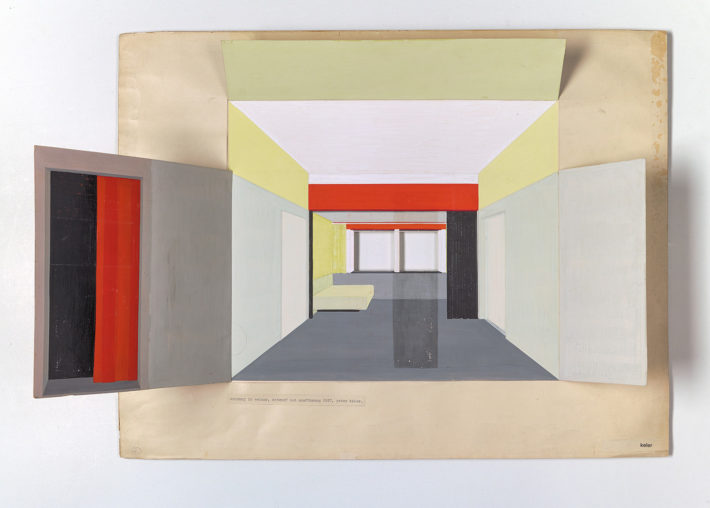

Peter Keler, Apartment in Weimar, design and execution, 1927, gouache on paper. Private collection, the Netherlands.

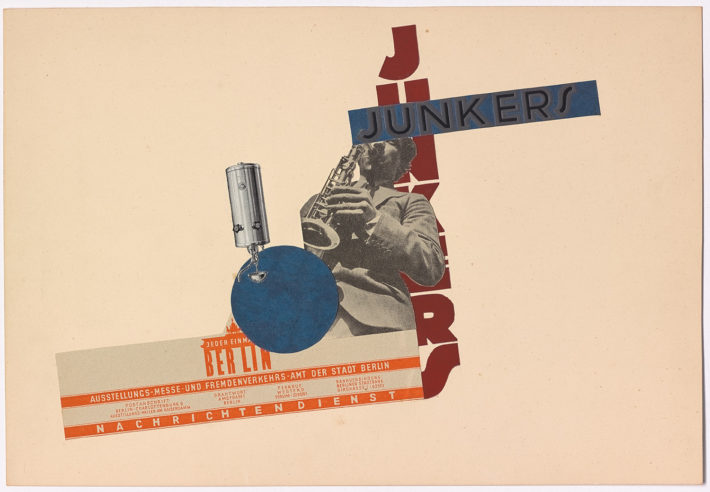

Johan Niegeman, Junkers, 1929, paper collage on card. Private collection.

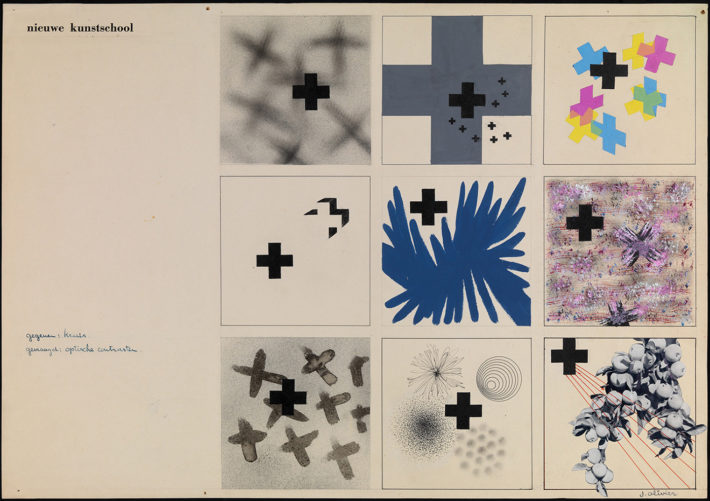

Jettie Olivier, student work done at the Nieuwe Kunstschool, c. 1938, gouache on paper. Private collection.

Bertus Mulder, color study done in Helene Nonné-Schmidt’s class at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, 1956. HfG-Archiv, Ulm.

Marguerite Friedlaender and Franz Wildenhain (Het Kruikje, Putten), tableware, 1934-40, stoneware. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Photo: © Tom Haartsen.

Marcel Breuer, Four side tables, c. 1926, nickel-plated metal, painted wood. Private Collection, Germany.

Wassily Chair, also known as Model B3, designed by Marcel Breuer, 1925. © D Rose Mode.

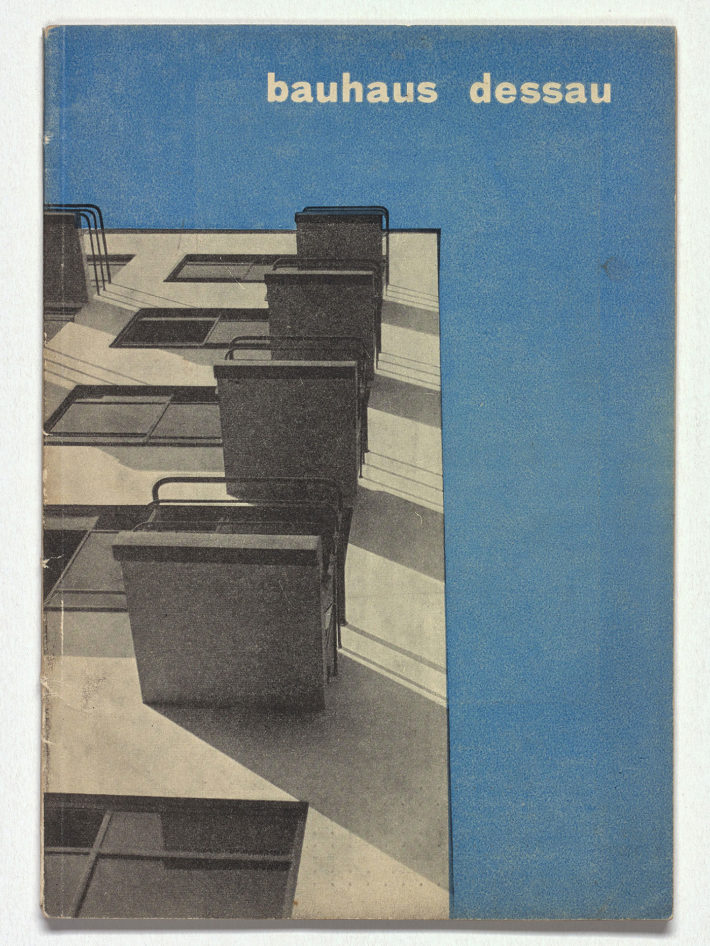

Herbert and Irene Bayer, Bauhaus. Dessau. Hochschule für Gestaltung prospectus, 1927. Private collection, the Netherlands.

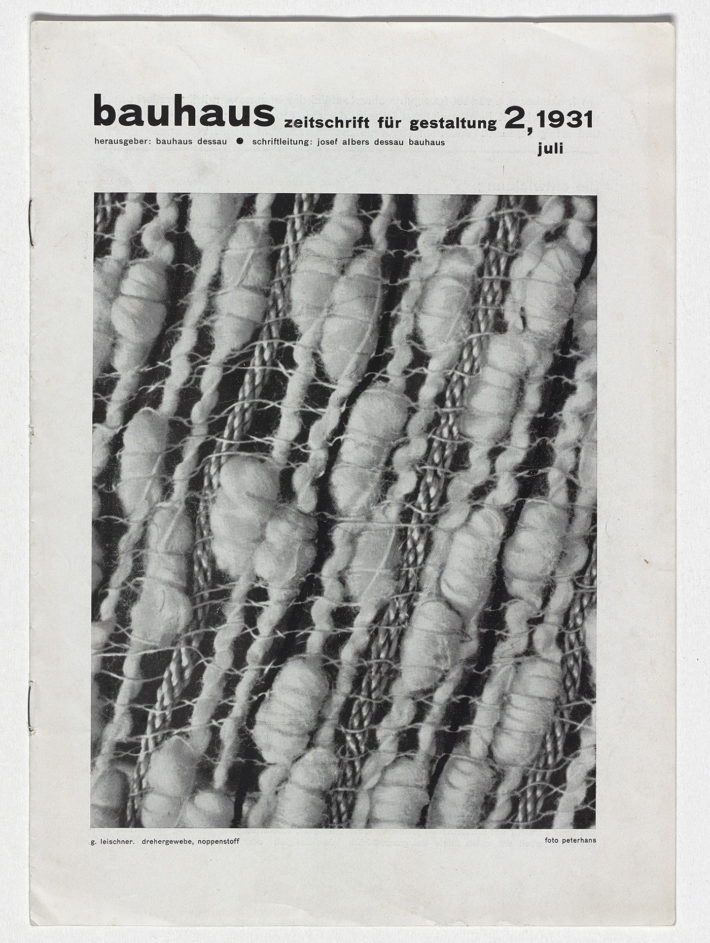

Cover of Bauhaus: Zeitschrift für Gestaltung 2, 1931, with photo of woven fabric by Margaret Leischner. Private collection, the Netherlands.

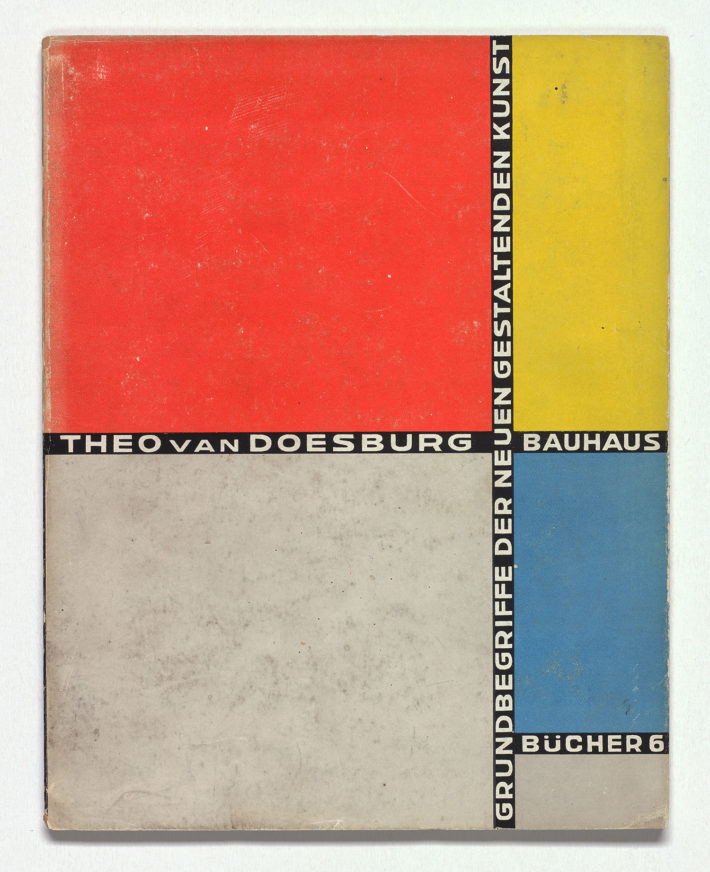

Theo van Doesburg, Grundbegriffe der neuen gestaltenden Kunst (no. 6 of the Bauhausbücher series), design Theo van Doesburg, 1925. Private collection, the Netherlands.

Issue of De 8 en Opbouw, January 11, 1936. Private collection, the Netherlands.

Marcel Breuer, ti 1a armchair, 1923, wood, textile, made in the furniture workshop at the Bauhaus in Weimar. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Photo: © Tom Haartsen.

Willem Hendrik Gispen, Giso 22, pendant lamp, 1927, milk glass, chromium-plated copper, manufactured by Gispen’s Fabriek voor Metaalbewerking, Rotterdam. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Photo: © Ad van den Bruinhorst.

Left to right: Walter Gropius, Wassily Kandinsky and J.J.P. Oud during the Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar, 1923. Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), Montreal.

Notes

1 Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius and Ise Gropius, eds., Bauhaus, 1919-1928 (New York: MoMA, 1938).

2 Mienke Simon Thomas and Yvonne Brentjens, Netherlands – Bauhaus: Pioneers of a New World (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 2019).

3 Marion von Osten and Grant Watson, Bauhaus Imaginista (London: Thames & Hudson, 2019).

4 Partha Mitter, “Teaching Art at Santiniketan: Some Unexpected Meeting Points,” in von Osten and Watson, Bauhaus Imaginista, 36-43, and Anshuman Dasgupta, “The Intimate and the Contingent: Art and Craft in the Pedagogy of Santiniketan,” ibidem, 44-52.

5 Andrea Maglio, Hannes Meyer: un razionalista in esilio. Architettura, urbanistica e politica 1930-54 (Milan: Franco Angeli, 2002), 135.

6 Ezio Bonfanti and Massimo Scolari, “Presentazione,” Controspazio, nos. 4-5 (April-May 1970), 7.

7 Giulio Carlo Argan, Walter Gropius e la Bauhaus (Turin: Einaudi, 1951).

8 Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (London: The Architectural Press, 1960).

9 Reyner Banham, “The Bauhaus Gospel,” The Listener (September 26, 1968), 390-92.

10 László Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision: Fundamentals of Design, Painting, Sculpture, Architecture (London: Faber & Faber, 1939).

11 Banham, “The Bauhaus Gospel,” 390.

12 Ibidem.

13 See among others Leyla Daybelge and Magnus Englund, Isokon and the Bauhaus in Britain (London: Batsford, 2019).

14 Banham, “The Bauhaus Gospel,” 390.

15 See the writings on the Bauhaus in Tomás Maldonado, Avanguardia e razionalità: articoli, saggi, pamphlets 1946-1974 (Turin: Einaudi, 1974).

16 Jorn Asger, Pour la Forme: ébauche d’une méthodologie des arts (Paris, 1958; reprinted by Editions Allia, 2001). See too Paolo Morello et al., La memoria e il futuro. I Congresso Internazionale dell’Industrial Design, Triennale di Milano, 1954 (Milan: Skira, 2001), 88.

17 Mirella Beini, L’estetico, il politico. Da Cobra all’Internazionale Situazionista 1948-1957 (Rome: Officina Edizioni, 1977), ch. II.

18 Tom Wolfe, From Bauhaus to Our House (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1981; reprinted by Picador, 2009).

19 Wolfe, From Bauhaus to Our House (2009), 57.

20 Fulvio Irace, Codice Mendini (Milan: Electa, 2016).

21 Which of the many Bauhauses? In reality, the maxim was first pronounced by the great Louis Sullivan, teacher of Frank Lloyd Wright not Mies.

22 The interview appeared in the Correio Braziliense on December 14, 2008.

23 Gabriele Neri, “Torna la casa di Gropius,” Il Sole 24 Ore (Sunday supplement, May 25, 2014), 30.

24 Letter from Waldemar Alder to Hannes Meyer, June 16, 1947, quoted in Maglio, Hannes Meyer, 138.

25 Paul Betts, “The Bauhaus in the German Democratic Republic—between formalism and pragmatism,” in Bauhaus, ed. Jeannine Fiedler and Peter Feierabend (Cologne: Könemann, 2000), 42-49.

26 Bonfanti and Scolari, “Presentazione,” 6-7.

27 On the subject see Ulrike Müller, Bauhaus Women: Art, Handicraft, Design (Paris: Flammarion, 2009); von Osten and Watson, Bauhaus Imaginista.

28 Van Bo Le-Mentzel, ed., Hartz IV Moebel.com: Build More Buy Less! (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2012).

29 Enzo Mari, Proposta per un’autoprogettazione (Milan: Simon International, 1974).

30 Annemarie Jaeggi, “La scuola dell’avanguardia. Bauhaus: un modello concettuale,” in Christoph Frank and Bruno Pedretti, eds., L’architetto generalista (Mendrisio: Mendrisio Academy Press/Cinisello Balsamo, MI: Silvana Editoriale, 2013), 163-77.