13 October 2016

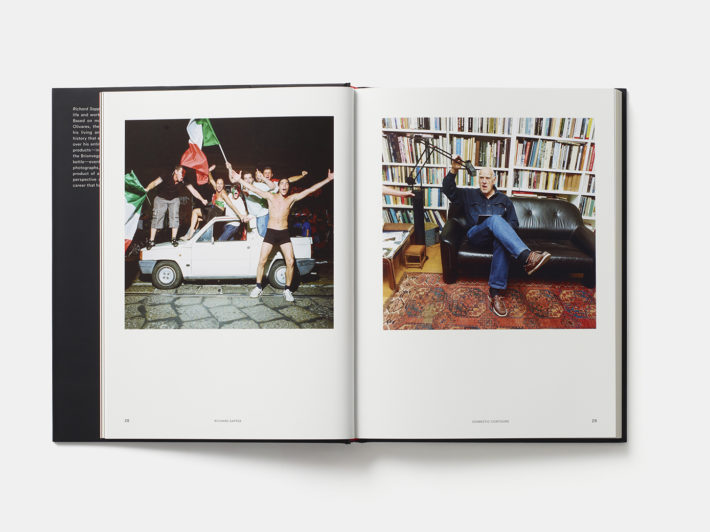

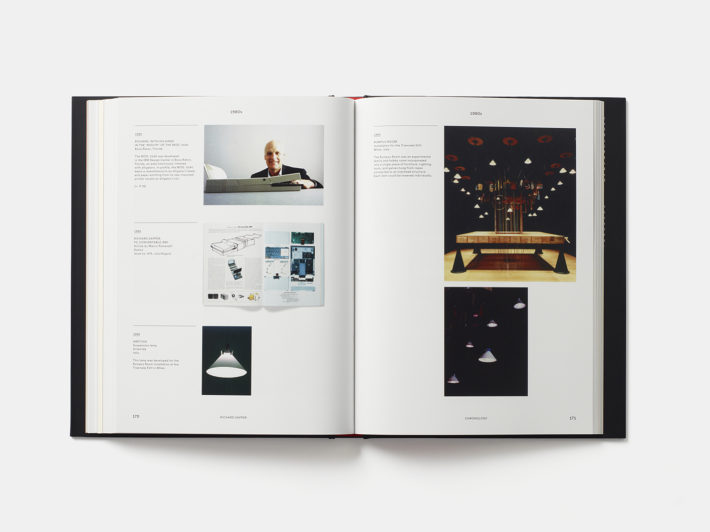

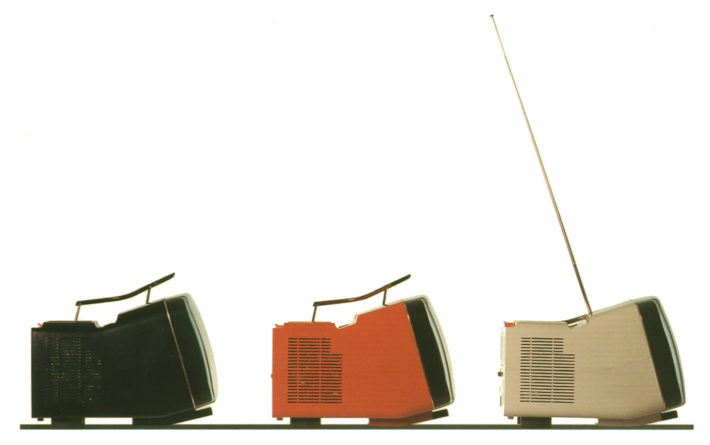

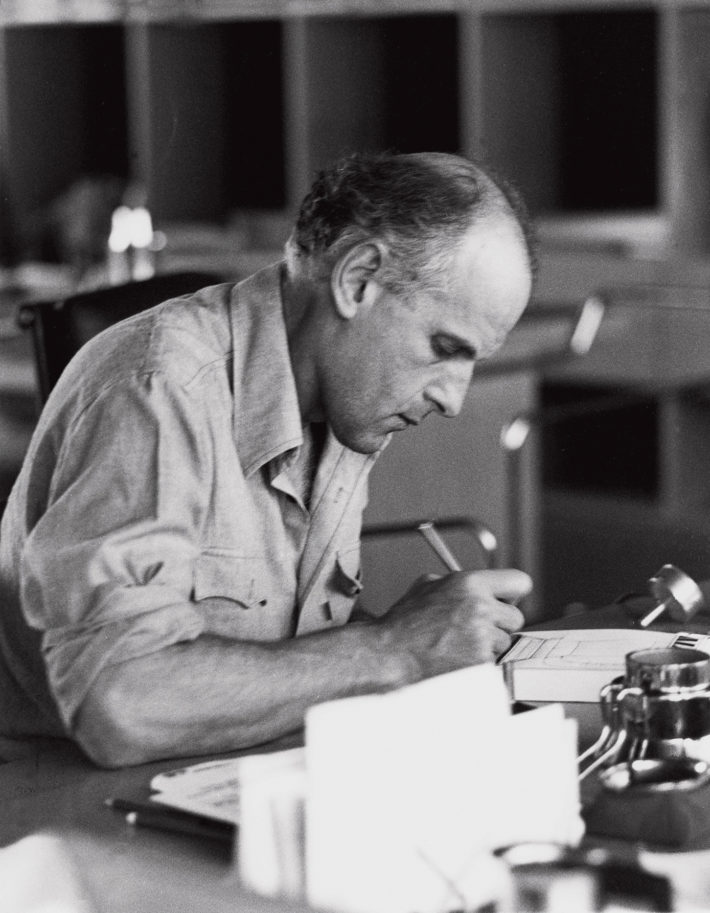

Anyone who knows Richard Sapper will smile at that black monolith with a red dot that is the monograph put together by Jonathan Olivares for Phaidon. The young American designer has paid homage to his great German counterpart by adopting his language and packaging a literary ThinkPad: in fact Richard Sapper edited by Jonathan Olivares imitates the salient features of the IBM laptop designed in 1992, the celebrated black box with a red TrackPoint that is one of Sapper’s most long-lived designs (since 2005 it has been produced by Lenovo). A creator of functional objects of ascetic beauty like the Tizio lamp for Artemide, radio and television sets for Brionvega or the whistling kettle for Alessi, the German designer was not a great talker: he preferred his designs to do it for him. Those who went to interview him, at his house-cum-studio in front of Milan’s Castello Sforzesco, were met for the most part with terse responses and the odd anecdote, interspersed with sudden movements as he went in search of images better suited to expressing his ideas than words. It is no surprise that Olivares needed 50 hours of conversation, drawn out over eight years, to gather the material needed to produce this volume, published just a few months after the death of its protagonist (on December 31, 2015). The book commences with a photo-essay entitled “ Domestic Contours” by Ramak Fazel, who takes us with his Rolleiflex into Sapper’s home-offices in Milan, on Lake Como and in Los Angeles, the creative settings of a man who always refused to work out of a proper office. The second part is an “oral history” in which the author’s voice alternates with Richard’s (as he is affectionately referred to in the book), a vivid way of telling us the fascinating story of his life and explaining to us what industrial design really us. The last and most substantial section, Chronology, reflects the prolificacy of the designer, who created automobiles, bicycles, computers, furniture, TV sets, kettles, cooking pots, graters and faucets, but also studied the problems of urban transport, in order to “find a means of transport that modern man can carry about, like an umbrella,” convinced that the priority was to “change the way we live, the way we operate the machinery of our lives.” On the last three pages find his answers to the questions put to Charles Eames for the exhibition Qu’est-ce que le design? (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 1972), which provide us with a wonderful synthesis of the essence of the man, whose response to the last question—“What is the future of design?”—is an offhand “No comment.”

Algol, design by Richard Sapper and Marzo Zanuso for Brionvega, 1964.

Static , design by Richard Sapper for Lorenz, 1959.

Tizio, design by Richard Sapper for Artemide, 1972.

Richard Sapper with Alberto Alessi.

Richard Sapper and family.

Richard Sapper, Milan, 1978.

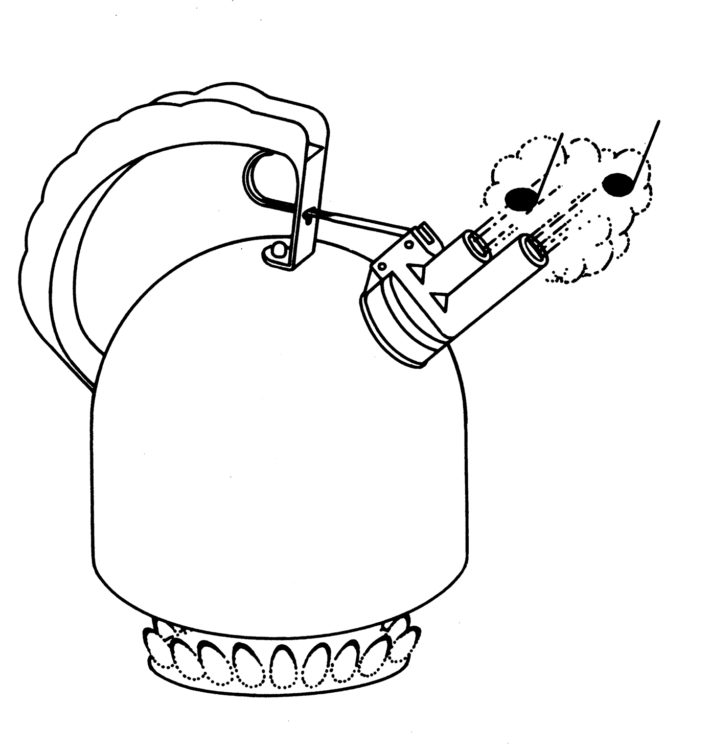

9091 , design by Richard Sapper for Alessi, 1983. Sketch.

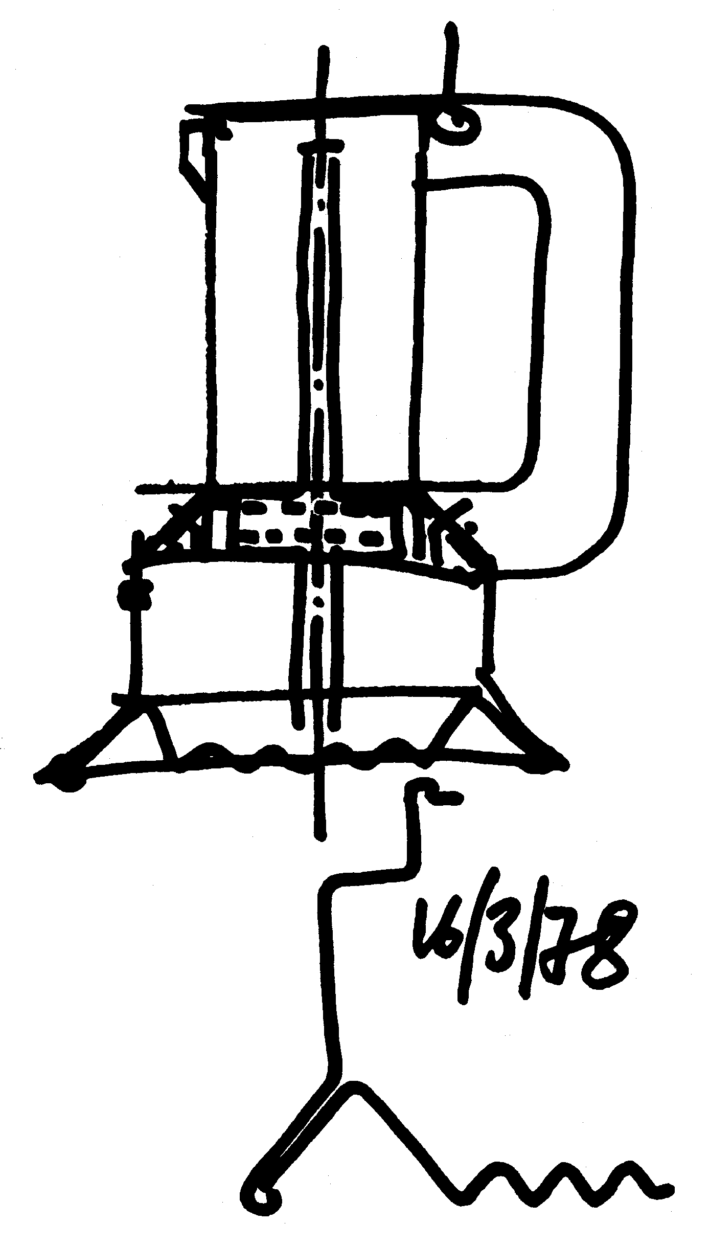

9090, design by Richard Sapper for Alessi, 1978. Sketch.