15 February 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s John Maeda’s turn.

Klat #03, summer 2010.

John Maeda is about to catch a plane, he has forty minutes before it’s time to board. With him is Hans Ulrich Obrist. Guess what happens in those forty minutes? Easy: Hans sits John down at a table and the result is a wise, witty and lighthearted conversation. Unforgettable. They talk about Maeda, his beginnings and his works, about simplicity, teaching and above all life, which is never long enough. There’s not a nanosecond to lose…

I am very excited to be doing this interview with you John. You’re about to leave for the airport so we haven’t a second to lose…

Life is short.

I wanted to ask you about your beginnings. I’ve read that Bruno Munari, Paul Rand and everyday life were important influences. How did you come to design?

I didn’t know about design until I was a junior at MIT. I was good at drawing and mathematics, but I had never heard of this discipline. I discovered it through Paul Rand’s book. I was doing my research papers and a secretary said: “your research papers look excellent.” That made me think it is important how things look and that one should think about design. That’s how I began to be aware of design. Paul Rand’s book started me on that path.

And what about Munari? Was that later?

Yes, when I was in Tokyo I saw his exhibition and he impressed me like Paul Rand had done, but on a more intuitive and raw level. I would say that Rand appeared to me as a quintessential designer while Munari was more of an artist. I like this weird “in between” place they occupied.

What did Rand give you and what did Munari give you?

I think Rand gave me sense of structure and Munari gave me sense of play. They were similar in many ways, but I would say Munari was more play and structure while Rand was more structure and play.

In terms of your design and art work, which would be your breakthrough piece? Where would your catalogue raisonné start?

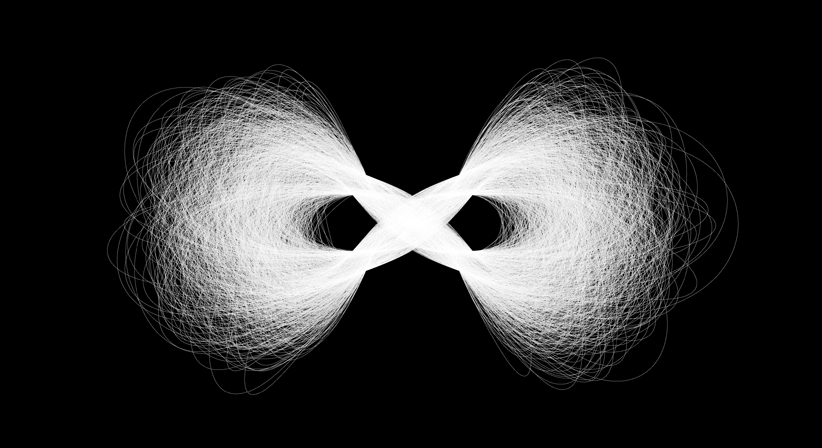

The first breakthrough I had was when I drew a kind of black and white symbol of infinity (Infinity, 1992-’93, ed). After that, there was a long drought during which I did many other things, but nothing that really made much sense. I think the second breakthrough happened when I designed a little rope to walk around on the floor with a pen attached to it. That was another moment where it all made sense – something that has happened to me not more than two or three times.

You really feel an epiphany.

Yes. In those moments I said to myself: “Oh, this is right.” All the rest I did at the time was kind of wandering.

So the first project you did was a computer program?

It was a computer program that draws a loop millions of times. A simple program, the first one combining creative thought with mathematical thought.

It was a sort of pioneering moment when you started…

I was at the right place at the right time.

John Maeda, Al Infinity (print), 1994. Courtesy: Maeda Studio

Can you tell me how that happened?

It was a complete accident. If I were to draw a map, it would be about the accident really.

Tell me more about this map.

The map is about how the world changes, how the economy changes, how technology goes up and down, how pessimism goes up and down, and about how in the moments in which pessimism is high and economy is low, technology is falling. The map is about the great transformative moments. I happened to be there in one of these moments. I was lucky to be there. It’s a map of the past, as everything is always the same. It just happens over and over.

As Alighiero Boetti once told me, everything moves like a wave, with highs and lows, intervals, pauses and silences.

Exactly. It’s about where you find yourself: down in the gully or the valley.

What year was it when you started?

I would say I started in fourth grade, when I was about ten.

So late seventies?

That’s when my teacher said I was good at math and art.

Were you a Wunderkind?

No, because for my father I was only good at math. He didn’t care about art. But I began to be aware that there was something there.

Was the economy low when you started? What was your position on the wave?

No, the economy was rising and technology was rising; pessimism was at a halt, neutral.

So basically it was the right moment to start?

It was the right sequence of moments. The computer hadn’t yet taken off, I was rather good at drawing and good at making programs, but I was always missing something; I was always very quiet. It wasn’t until after graduate school I realized I couldn’t be quiet anymore, because if I went on being quiet I couldn’t do anything.

So you needed to talk.

Yes, and I was the shyest guy. I hated talking, absolutely.

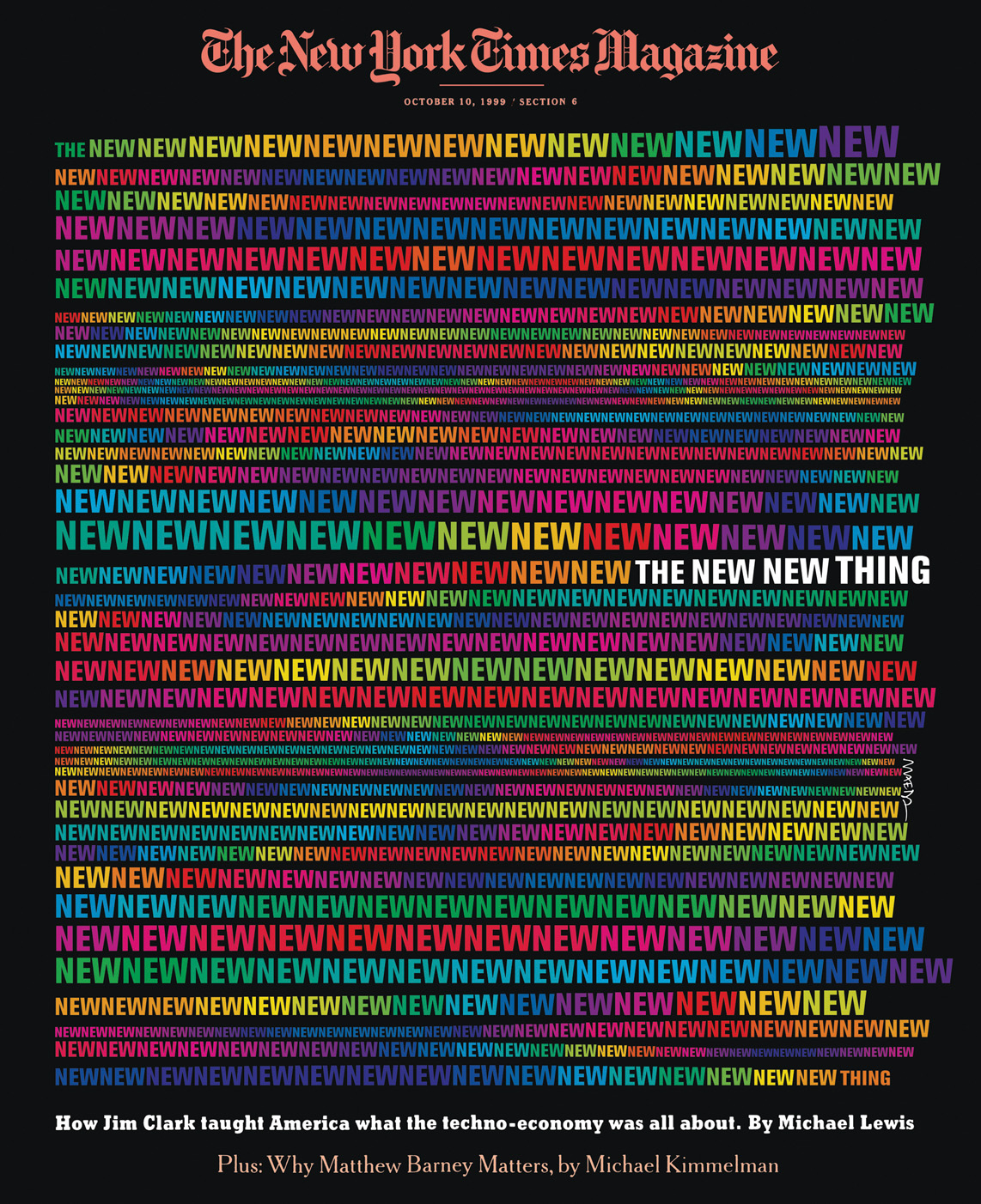

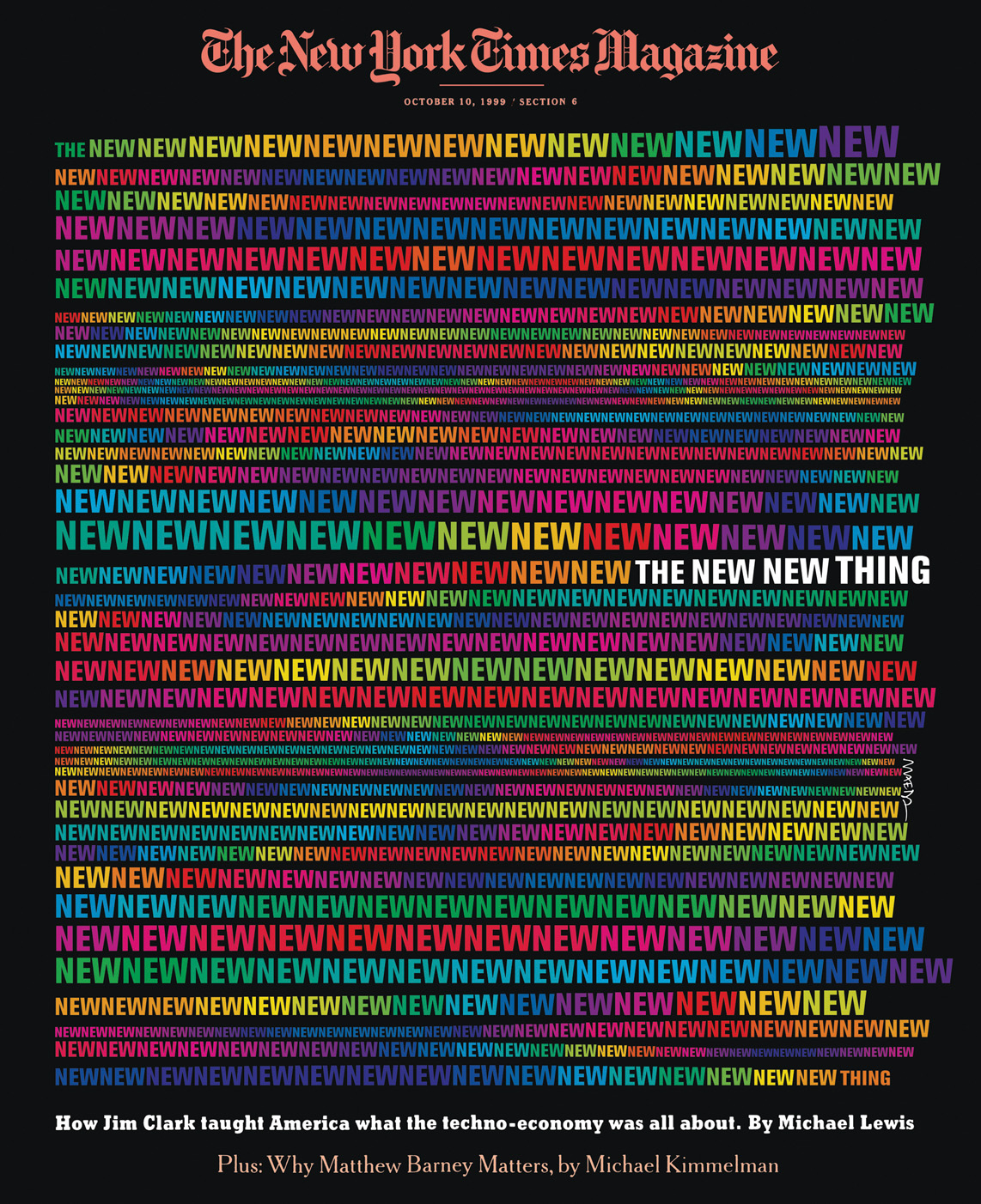

John Maeda, The New York Times magazine (cover) 1999. Art director: Janet Froelich

And what was your next epiphany? What came after your infinity program?

Many kinds of things. 1993 and 1996 were my most productive years. In 1996 I principally worked on paper, 1993 was more about computer. But it wasn’t until roughly 2002 when I almost casually made a little robot spinning around with a pen attached to it (Robot Draw, 2003, ed). The moment I drew this figure on the computer screen I realized how this robot drawing a line, to me, had a real meaning, because it was a real line, but yet computational. After that, I began making all kinds of things in the physical world. I made little boxes that sit on the floor that you touch with your foot, I made plastic sculptures, I made palm paintings.

So you went from 2D to 3D.

3D plus time. I made a whole series of works on this concept (Post Digital, 2001, ed.). For example, I made some black and white paintings that had a small window in them in which I placed Palm Pilots I had bought. Then I wrote a computer program that made the palm pilot ask itself in a self-contemplating manner: “What is this?”

Let’s talk more about what happened in ’93 and ’96. Many of your books were published in the nineties.

In ’93 I began to make lots of things for the computer – consider this is pre-Internet. I had a friend who produced all my books (Digitalogue, ed), the Reactive books we called them. He was a real believer. I published, I think, four or five books, little paper pieces that I designed and that had a floppy disk or CD Rom to go with them.

So you became a book machine?

Yes, like you! I was a book machine and I was always very adamant about doing it myself. I had always thought that artists and designers made everything by themselves. But that was of course a false impression. Later in life I realized that everybody has an assistant, or people they work with.

Do you have a big office?

Oh no, it’s always been a desk.

And when did that change?

It’s never changed.

You say that you learn a lot from your students. I remember reading in Designboom that your students are source of information and that you don’t see the office as a school, but the school as an office. Is that correct?

Well I wouldn’t say that, because I never liked my professors that were often likely to take all the students’ work. When I became a professor, I gave myself a strict policy: my job was to build the students’ careers and my own work I would do at night. Like Batman, he was my idol.

That’s a bit how it works for me: during the day I have my museum job and at night I do my books.

See, you are like Batman too.

That means you are not sleeping much… How many hours?

From four to five per night.

That’s the same for me.

I believe that life is precious. I was lucky because in my twenties the famous designer and sculptor Igarashi Takenobu, introduced me to this professor from California. He was in his sixties at the time and he was a very strange man. He used to call me in Tokyo from Los Angeles at any time of the day and of the night for a chat. I thought he was crazy. He behaved like a teenager, you could see it in the way he walked and acted in general. One day I was having lunch with him in Los Angeles and he asked me: “Do you know why I’m like this?” And I said: “Well, you know you’re different.” And he said: “Yes. In my twenties I was just like you: a young professor, my career was rising, I had a wife, we were expecting a baby and everything was fantastic. We bought a house, our whole life was planned. One day she came home and said she felt something was wrong, so she went to the doctor and he said she was fine. So she went to another doctor and he said she was fine too, but because my wife was a medical student she could study her own body and she discovered she had cancer. One month after she gave birth, she died.” He told me that was the reason why he planned his today as if there should never be a tomorrow. He simply assumed there wasn’t going to be any tomorrow. That’s how I became aware that it’s not forever. Another person I met was Mr. Fukuhara, the chairman emeritus of the Shiseido Corporation – the Chanel of Japan. Mr. Fukuhara showed me some medical research all set in graphs, in which depending on how old you are, you can see how your body at first increases in possibility and then falls, how your eyes are really great then they fall, how your brain is great and then, when you get to sixty, it falls, and so on. When you see this graph – I like these graphs – you see how things don’t go any further, how there is an end. So to your point, I’m trying to make the most of it.

There’s not a nanosecond to lose… You have the amazing skill to do your own work at night and to be a great educator during the day. You’ve taught and inspired a whole generation of designers, web designers and artists. Ben Fry e Casey Reas were your students about ten years ago, for example.

They were great. They were special. I used to spend a lot of time recruiting people. I would recruit people who were hybrids – neither artists, designers, technologists or scientists. They were in this weird “in between” place. Ben, Casey and others like Golan Levin and Peter Cho, were all very talented people. But there were many more that were talented. I would find people on the web and ask them: “Hey, do you want to come to graduate school?” And they would write back to me and say: “I didn’t go to college, professors are stupid.” But it was great to find out how many people thought that they didn’t need to go to college because they had friends they could learn from. I learned all these things through experience. But Ben, Casey and the others were all much better than me at different things; working with them, I realized that I didn’t have to do this work anymore, because they were so much better and more complete than me. I’ll never forget the time when someone sent me a link to a guy called Yugo Nakamura (he’s the number one Flash guy) who had taken my last major interactive piece – a black and white program entitled Tap, Type, Write (1998, ed) – and turned it into this amazingly beautiful thing. Mine was very basic. He finished it. His version really struck me and made me think that I didn’t need to do that and, to be honest, I couldn’t do that.

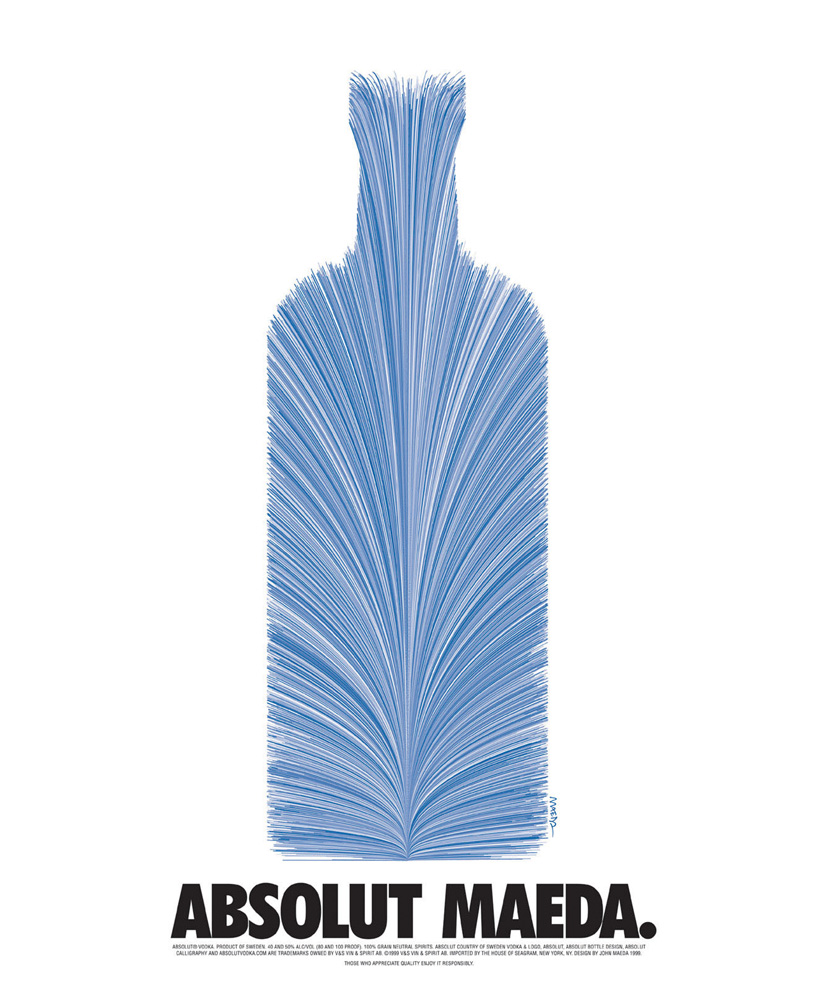

John Maeda Absolut Vodka

So you moved on to something else.

That’s what I did.

Did you stop doing interactive pieces all together?

Yes.

What prompted the decision?

I just knew I wasn’t as good as other people. I came back to interactivity later, in the two-thousands, when I began to make simple text programs. Little web programs, like the credit card debt calculator (Credit, 2006, ed), which is one of my favorites and apparently one of my most popular things on the web.

A credit card…?

A debt calculator. When my younger brother became bankrupt I really couldn’t understand how such a thing could have happened. A simple credit card debt calculator was the solution. Another program I did is one that takes text and randomly shrinks it (Reduce, 2007, ed). These are just meaningless things to play with – old school non-animated ASCII text.

Are you working on any new typefaces?

No. But I am really interested in words. I love words and sentences.

Writing is an important dimension in your multi-dimensional practice. There is your text piece, your interactive piece, your books, then there is education, teaching and your website. You’re also writing your Simplicity manifesto. What is the role of writing in your life? Is it a daily practice?

I really respect writing because I feel it is like painting with words. I love to look at words and I love the structure of an essay. Besides, I don’t think I am particularly good at it, so I am always trying to figure out how to improve myself. Practice makes perfect.

Can you tell me about The Laws of Simplicity? Was that another one of your epiphanies?

Yes, that was a big epiphany. I realized that technology was on the rise and people’s confusion was high and, what’s more, although I’m an MIT-trained expert in technology, even I was having problems keeping my computer running. So I thought: “If I have problems, everyone must have problems.” I thought it was worth talking about this and how things had got so complex with computers, so I started a blog about simplicity, just writing as if I were talking out loud. That’s how it began.

In a world where things tend to become more and more complex, can simplicity itself be an “anti-cyclical” alternative?

Yes, exactly. While everyone wanted more, I was thinking that maybe we should have less.

So was it about “less is more”?

Not only that. The idea of simplicity is complex.

Any other writing epiphanies? Did you write any other manifestos?

Oh, many.

Can you tell me about your manifestos? I was reading Jaron Lanier’s You Are Not a Gadget, which is one of the twenty-first century manifestos.

Like everyone, I have lots of things I never published, written down on napkins and scraps of paper. The manifesto that I am trying to write now is about leadership and how it ties to art and design.

And that ties in with your work at the RISD, Rhode Island School of Design. You were a protagonist of MIT – the Bauhaus of the twenty-first century – and you decided to leave that for Alexander Dorner’s Rhode Island school and museum. You explained to me yesterday that it was a very conscious decision to leave the technology environment, go into an art school and, once there, to talk about leadership. I am very curious to hear more about this new chapter.

Being a president I’m forced to understand what leadership means. Most people are first a professor, then a department head, then a dean, and then vice-president and provost. I became president all of a sudden and had no preparation, so I had to figure out what was the leader’s job fairly quickly. When you are the artist you are the person working against everything.

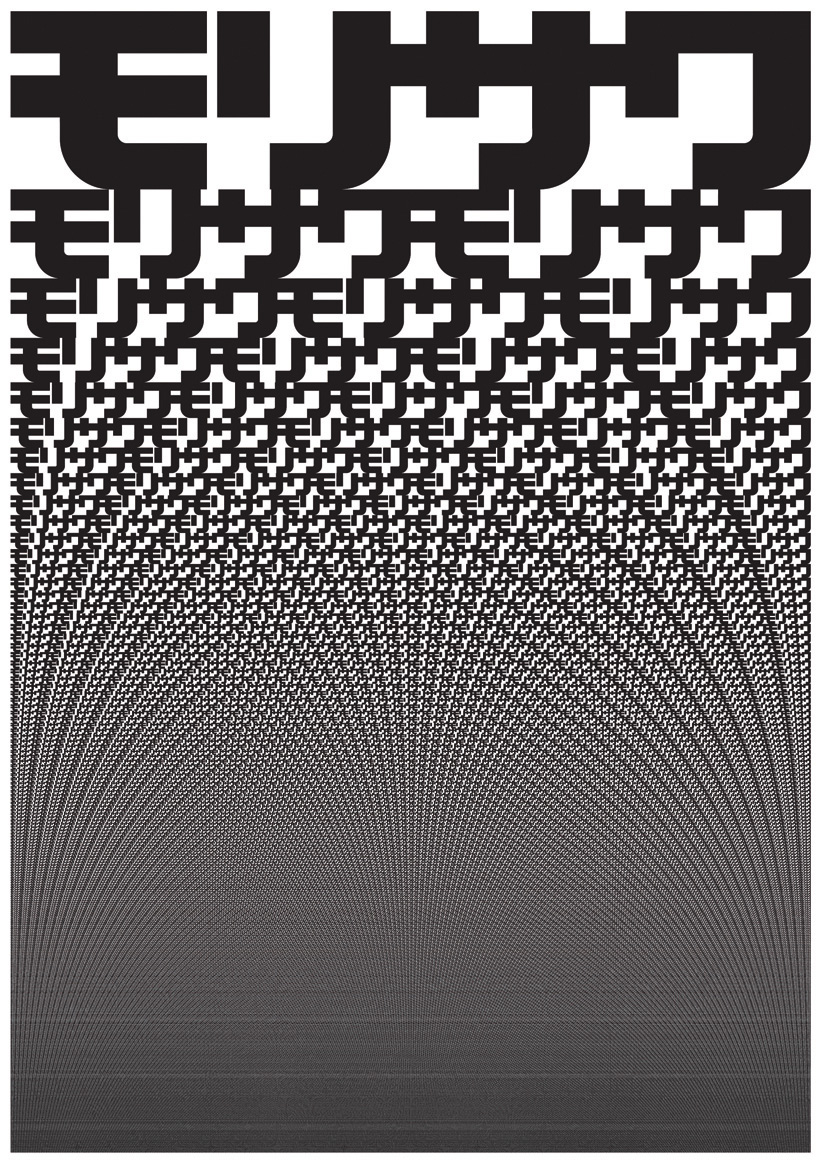

John Maeda, Morisawa 8, (poster) 1996. Courtesy: Maeda Studio

Do you mean against the system?

Yes. Suddenly I’m the system. I’ve been trying to understand how to remain creative as a leader of a system and, at the same time, how to avoid becoming just another leader, because if that were the case then they could simply hire somebody else. I feel like I’m in an exhibition, where I am put on exhibit even though I don’t perfectly fit. But if I perfectly fitted then I wouldn’t be important to the collection, so I’m trying to figure out how I can be the reason why I’m in the collection and be responsible at the same time. I don’t want to be a pink flower in an exhibition of concrete blocks. What I want to find out is how to be a pink block of concrete.

You said that you see your institution like an XL gene. Can you explain that to me?

I think that now with the economic setback and the world reforming, RISD can be a kind of DNA you insert into this reforming process. The nice thing about being the president of this school is that once – when I was an artist and designer – I was a tiny gene, a little piece of the puzzle. Now that I lead this school (that’s been around since the nineteenth century and that has the most beautiful museum that you love and is responsible for the birth of your life as a curator), I’m part of a bigger gene. In theory, if things work out, the gene will mutate and help to redefine this world that is reforming.

Do you have any concrete projects, exhibitions or structural inventions at the school that you can talk about?

I think the school is on a good track. I think that it has a great museum, a great curriculum, and that everything is working fairly well. However, in the world there is change. The world of art has changed, the world of design has changed, the world in general is changing. Part of my challenge is to find a way to bring that sense of change into a place that obviously has resisted change in order to become great. It’s this that I’ve been thinking about. When something good has been able to resist change and observe the outside, things just turn out to be great. Once you begin to merely look outside you begin to adjust yourself and become like everything else. RISD has managed to be very independent, very the way it wants to be, so the question is: how do you keep this kind of independence and look at how the world is co-dependent, without watering it down to what everything else is?

Do you have any projects, dreams or utopias too big – or too small – to be realized?

I have a whole series of sculptures I was supposed to build over the last few years. I had a series in Tokyo one year, where we used all my old computers (post digital, 2001, ed). One became like a balance beam, another one became like a self-drawing machine. There are few books that I want to work on too, and something is still in my head.

New books?

Yes, new books.

Do you have any kind of XL projects like cities, urban sculptures or something of the sort that you want to design?

No, not at all. I can’t do these sort of things. It takes a different kind of power.

So you’ll never go into architecture or urbanism. I was wondering if there will ever be a “John Maeda building” one day.

No. Most presidents like having buildings, but I don’t really care for buildings. I would rather spend the time and money on programs.

Rainer Maria Rilke wrote a little book entitled Letters To A Young Poet. What would be your advice in 2010 to a young designer or artist?

I think I would advise the young designer to study a lot, to study history as much as possible and to study how computer science works, for computer science is the foundation of our world today and of information. To the young artist I would say it’s important to isolate from all the influences and at the same time to be aware of what’s out there. I would say that technology is not that important, but it’s important to be able to critique, from a real stance. I’ll never forget the time I was in an art school giving a talk in which I said that I had stopped making things for the web. This person came up to me and said: “I’m so glad you said that, because I don’t understand all this html stuff, so if you’re going to stop I’m going to stop too.” I said: “No, you don’t understand. I can choose to stop, I understand it.” Understanding is crucial today.

John Maeda, The New York Times magazine (cover) 1999. Art director: Janet Froelich

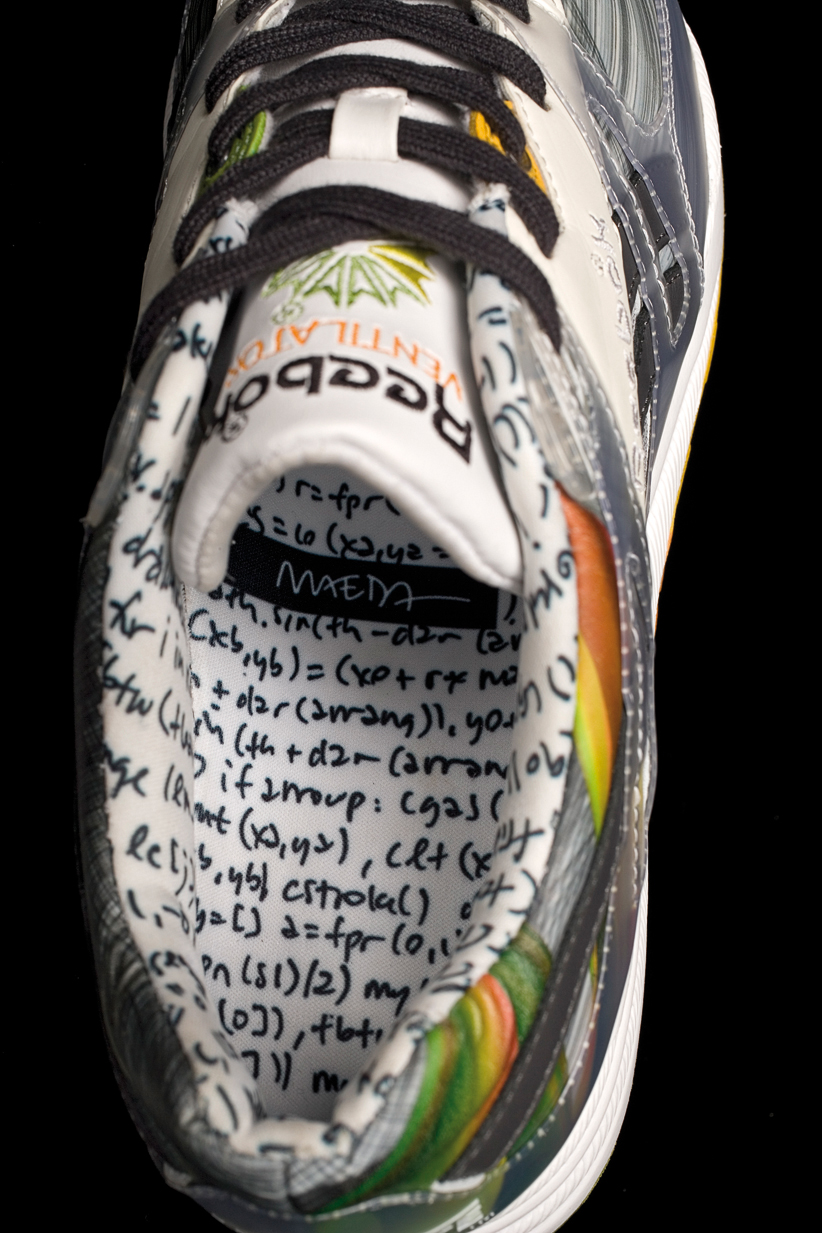

John Maeda, Reebok Timetamium (limited edition), 2008.