25 November 2014

To paraphrase Jep Gambardella, Barnaba Fornasetti is not simply an artist of the high life in the marketplace of Milan: he is the king of artists of the high life. He doesn’t just organize parties, he has the power to make them a success. Born in 1950, son of the Milanese painter and interior decorator Piero Fornasetti, Barnaba has always been surrounded by a colorful and many-sided great beauty. After studying at the Accademia di Brera and before embarking on the collaboration with his father, he worked with several designers, on magazines, as a creative director. On Piero’s death, Barnaba took over the family business, renewing the tradition of the studio with new products and reissues of quality pieces. His track record is studded with collaborations and designs for tiles, furniture, lamps and textiles, without forgetting the many exhibitions around the world, the showrooms, the books, the recent retrospective at the Milan Triennale and, finally, the parties. Indeed, the most celebrated party at the Salone del Mobile, the one to which everyone hopes to be invited: “The success of my soirées is due primarily to this time of ours in which no one is able to organize a party any longer. The problem, however, is that year after year everyone is expecting the end-of-Salone party. And I don’t always have the desire and the strength to do it.”

Can you explain to me the secret of a successful party in Italy?

It’s purely a question of magic, as with design. A minimum of organization is indispensable, but the success of a party depends essentially on a strange combination of factors that cannot be clearly defined or orchestrated.

Baciamano entomologia, design by Nigel Coates in collaboration with Barnaba Fornasetti, 2014.

Just magic then?

Let’s recognize too that I organize it during the Salone del Mobile, and that it’s the last party of the event, when everyone is fed up with parties that are intended exclusively to publicize a product. I’m no saint, I also want to promote my brand, if that’s what we want to call it. But people come to my party to have fun, enjoy themselves and eat good things. That’s all.

A question on behalf of those who are not on the guest list. What’s the party like?

Listen, I don’t like to talk too much about this party. This year over 700 people turned up and believe me, I don’t know where to put them anymore. Everyone talks about it, everyone wants to be there, and I’m forced to put a limit on the numbers, which is the last thing I want to do. But my home is small, and old. I don’t know what to say, I’ll have to change my job.

OK, let’s change the subject and talk about your real job, design. What do you think about starting out with the meaning of the Salone del Mobile for Milan?

In reality, I’d like to begin in provocative fashion as Enzo Mari did in the interview you conducted with him.

Don’t tell me that you’re a Communist too.

No, but I’d like design not to be the main subject of this interview. In any case, to answer your question: the Salone del Mobile is certainly important because it is the only moment at which Milan becomes a cosmopolitan city.

And Expo 2015, which starts in a few months?

The Expo is already a depressing example of the Italian discontent that we are hoping to shake off. Italians have this gigantic defect, notwithstanding the imagination, the creativity and the many qualities that others don’t have.

Creativity is passed down in the family. If it’s not indiscreet to ask, why have you no children?

It was a conscious choice, for the survival of the planet. The Earth has a limited supply of both food and energy. I can’t stand it that people go on talking about growth, and so I have chosen not to reproduce and I’ve found wives who agreed with me. What is stopping us from rebelling against those who, for economic motives, continue to corrupt politics and the other forms of coexistence?

One of the dishes from the Theme and Variations series, sketch by Barnaba Fornasetti, 2014.

In what way can we rebel?

There are various ways, violent and not violent. I’m a pacifist, but in self-defense… Even a Buddhist has to be able to defend himself when attacked.

Were you a rebel in your youth?

I quickly realized that violence gets you nowhere. As for all those of my generation, it was a peculiar time. At a protest in 1969 I was arrested for political reasons and ended up in jail.

Were you on the right or the left?

On the left obviously, I could never be on the right.

But how is it possible for people to be on the right?

Today it no longer makes sense to say I’m on the right or the left, and yet being on the left is an existential fact. By now a certain image has been established, in which the right is linked to corruption or to economic interests. Seriously, what is there that’s good on the right?

I wouldn’t know. Let’s change the subject and talk about something beautiful. The retrospective—or as you call it, the “retroprospective”—at the Triennale Piero Fornasetti, 100 Years of Practical Madness, which you curated, has been an incredible success. It ended months ago, but people are still talking about it.

Yes, it was an amazing event. I made a lot of effort to get an exhibition staged on the work of my father. In the end it was held at the Triennale, on the centenary of his birth, but I had been trying for years to convince the municipality to set the bureaucratic process in motion. The exhibition was proposed several times to more than one administration, from Moratti’s to Pisapia’s.

Other exhibitions on Piero Fornasetti have been organized around the world, like the one at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. But there was something special about the one at the Triennale.

The Triennale even made money out of it. It was one of the few exhibitions to have made a profit in Milan. Next March we’re taking it to Paris, to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. And it was popular with a broad section of the public: from two-year-old children to Gillo Dorfles, who is 104 and was the first visitor to the exhibition.

How was it conceived?

I’d been talking about it for years with Silvana Annicchiarico, director of the Triennale Design Museum. It wasn’t a foregone conclusion that I would be the curator, but we agreed that no one could have a better understanding of my father’s story than me. Eventually Silvana told me: “The exhibition is on, we have the funds.” The 37 000 visitors are evidence of its extraordinary success. There were three thousand people on the last day. And obviously a party there too.

Litomatrice, design by Barnaba Fornasetti, 2011.

So it’s true that you’re the king of parties?

A great party in the main hall, which went off very well, even though it wasn’t in the traditional setting of my home.

A few words on the way the exhibition was mounted, perfect for two artists like you and your father.

As a company we were responsible for preparing the exhibition. We had to keep under a certain figure—less than 40 thousand euros—but the aim was for everything to work perfectly.

As a company have you made money from it?

The response has been huge. Orders have gone up exponentially, to the point where we don’t know how to cope with them. To turn out our products it’s not enough to acquire another machine or hire another person. It takes years of training, little secrets of craftsmanship that no one reveals readily.

Does it bother you to talk about your relationship with your father?

No, it doesn’t bother me. But it’s a recurrent question, as is the one about the relationship between Piero Fornasetti and Gio Ponti. That’s a fixed one.

OK, we’ll skip it. What interests me instead is your relationship with botany. I know you have a marvelous garden and that plants and flowers are a constant source of inspiration for you.

It’s a passion that came with age. Having a garden is like using a palette, I am doing design there too, using forms and colors. What’s beautiful is that it is a form of slow design. You can’t plant a seed and expect the plant to sprout at once. You have to wait, it’s a school in patience.

Courtesy: Archivio Fornasetti.

So you rediscover more natural rhythms.

Yes, the problem is precisely that we have lost touch with the rhythm of nature. Human beings aim for the greatest speed, but generate only perversion: it has created a sort of metastasis that is devouring the planet. Today we struggle to remedy the mistakes made in the past. Recently I read about a young man who has found a way of eliminating plastic from the sea: now that is real design.

What can we do, then?

Stop using plastic in a stupid way, otherwise what’s the point in eating organic food.

When did this awareness start to emerge?

I belong to a generation that was already fighting for these things in the sixties and was laughed at. Governments and institutions only began to develop an appreciation of the environment in the eighties. Do you want to talk about the global justice movement?

Let’s talk about the global justice movement.

How badly the anti-globalists have been treated! And in the end they were right about everything. But rather than political problems, it’s a matter of structural elements that have to be dealt with. However, I remain optimistic.

What is it that gives you hope?

For instance, the fact that many companies are realizing that it no longer makes sense to go to China and are bringing their production back here, ensuring that Italian knowhow is handed down before it is lost forever. My production manager is from Senegal, he used to sweep the streets when he arrived in Italy. But he wanted to work and was able to steal the secrets of his predecessor from Puglia.

So there are good things in Italy.

There are important undertakings that are demonstrating material and spiritual growth. The point is not to just make consumer products: we were already talking about it in the sixties, and Herbert Marcuse and Pier Paolo Pasolini wrote about it.

What do you think of the new generations?

Poor things, they are in a really bad way. Although I sometimes come across young people who surprise me and allow me to retain hope in a return to manual skill, to the old ways, to design. But then there are also the dumbasses, the conformists.

Today you live and work in Milan. Why here and not somewhere else?

Because it’s here I’ve found my work. In reality, there was a time when I wanted to buy a castle at Larderello, in Tuscany, where the boric-acid fumaroles are. It was a manor house designed by the French architect who had designed the geothermal power plant for ENEL. I would have liked to leave just the store in Milan and move all the rest there, turning the castle into a beauty farm, a production facility, a total delight.

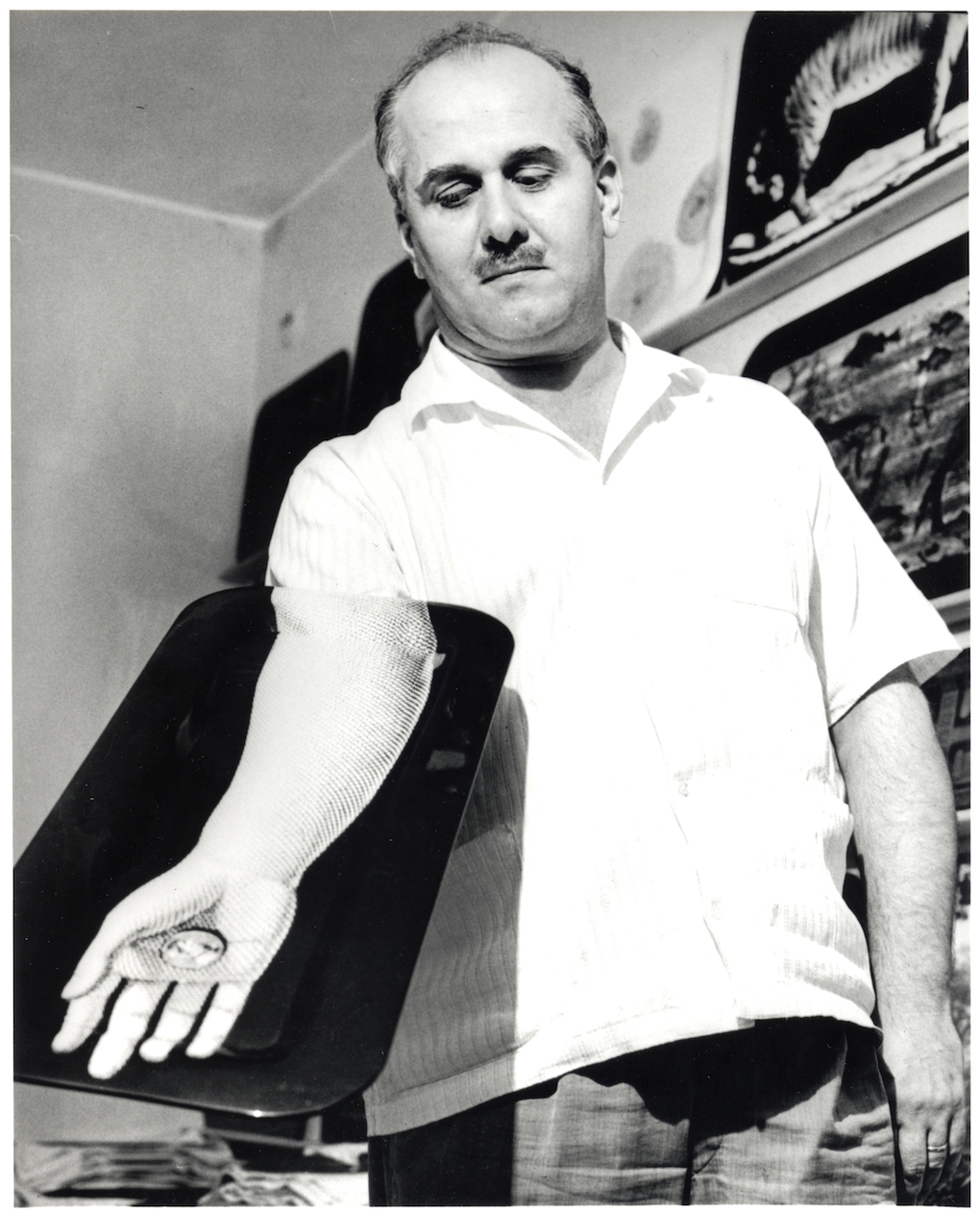

Piero Fornasetti. Courtesy: Archivio Fornasetti.

And in the end?

In the end Milan. My company is a small one. From the outside it might seem gigantic, but it has a ludicrous turnover, even if it is constantly growing slightly. The means are limited, in part because my father left me a mountain of debt. He was a genius, but from the business and financial point of view he was a disaster.

Tell me about him.

He was a creative man, an egocentric dreamer. He had a difficult character, but he could also be very loving. He wasn’t willing to compromise, and I remember him chasing away in a hail of insults anyone who entered the store in Brera asking for the pieces he had made with Gio Ponti in the fifties. His classic answer was: “Get out, you are pieces of shit, you are crooks, you have ruined Brera.” But he paid a price for this.

Did he quarrel with you too?

Yes, in fact I started to work with him when he was already old and had mellowed.

What was your father like when you were young?

He wasn’t on the left. He liked Prezzolini, bought Il Borghese and adored Montanelli, who for me was enemy number one. When I was arrested he had a moment of doubt. It didn’t seem possible to him that I had hit seventy police officers, or thrown stones and bombs. It was at that time that he started to distrust the police. Then he ended up going to the public school to talk to the students, he was on the front line.

A turbulent relationship?

When I was small he thought he could strengthen my character with a very strict upbringing. But having a governess was no use, because I became a rebel regardless.

And was your father a rebel, in his own way?

He was an antifascist, he couldn’t bear some of the regime’s absurdities. Toward the end of the war he even fled to Switzerland. Under the bombs, however, he had spotted interesting things: while others looked for food, he went searching for collectibles in the old houses.

What was it he spotted?

When he talked to me about the bombing raids, what came to his mind were chandeliers and stone fireplaces. He loved those things born out of an ancient knowledge.

We always come back to the same thing, the need to revive craft knowhow.

Today no one is willing to get their hands dirty.

Interviews serve to find solutions, give me a couple of solutions.

The young need to be convinced that it’s worth recovering certain skills. And then get rid of ignorance and the politics of terror.

One last thing: what do I have to do to be invited to next year’s party?

I don’t know if I’m going to have one, perhaps it’s going to rain.

You have to do it, it’s a tradition.

We’re going through a difficult phase in the company. After my father and me there is not going to be a third generation. I hope to have more time to devote to what I like doing. Believe me, the real luxury is time. We’ll talk about it next time, maybe at the party.

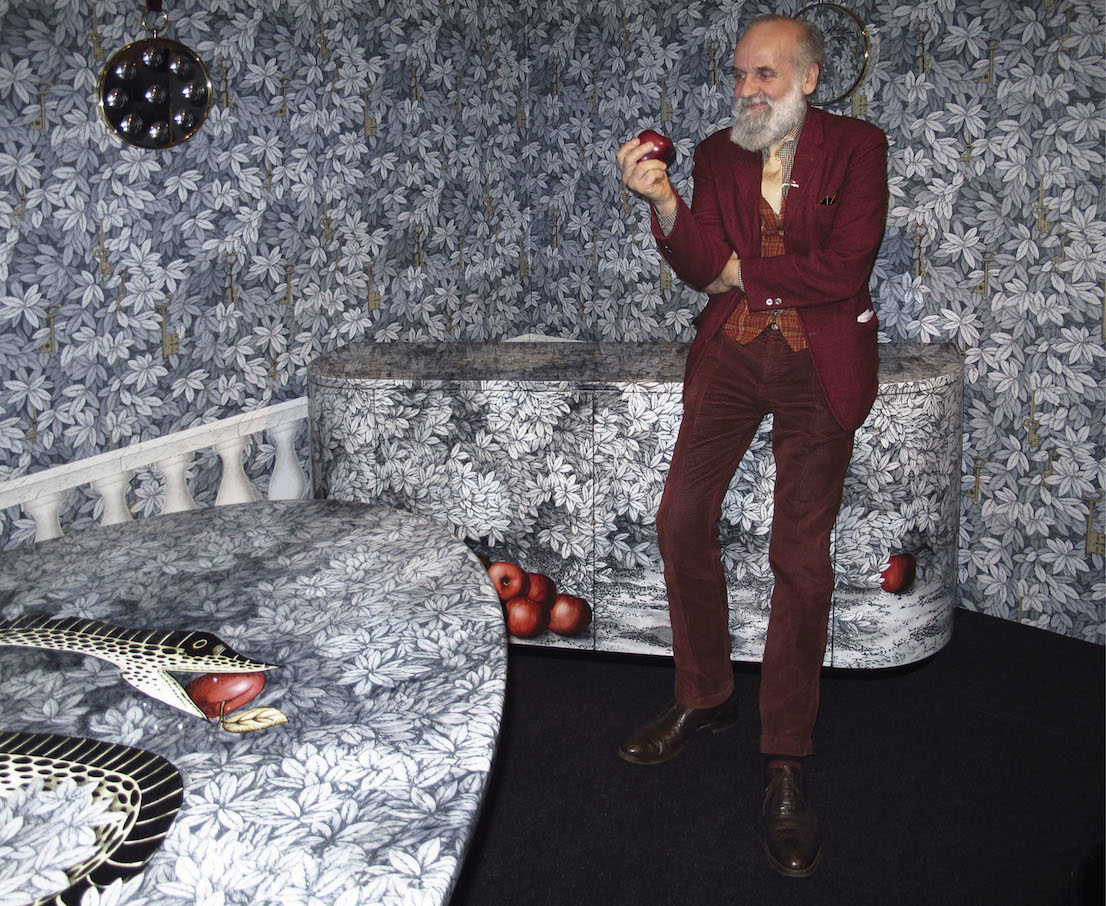

Barnaba Fornasetti in his showroom on Corso Matteotti for the presentation of the Fruit of Sin collection during FuoriSalone 2013.

High Fidelity, design by Barnaba Fornasetti, 2007.

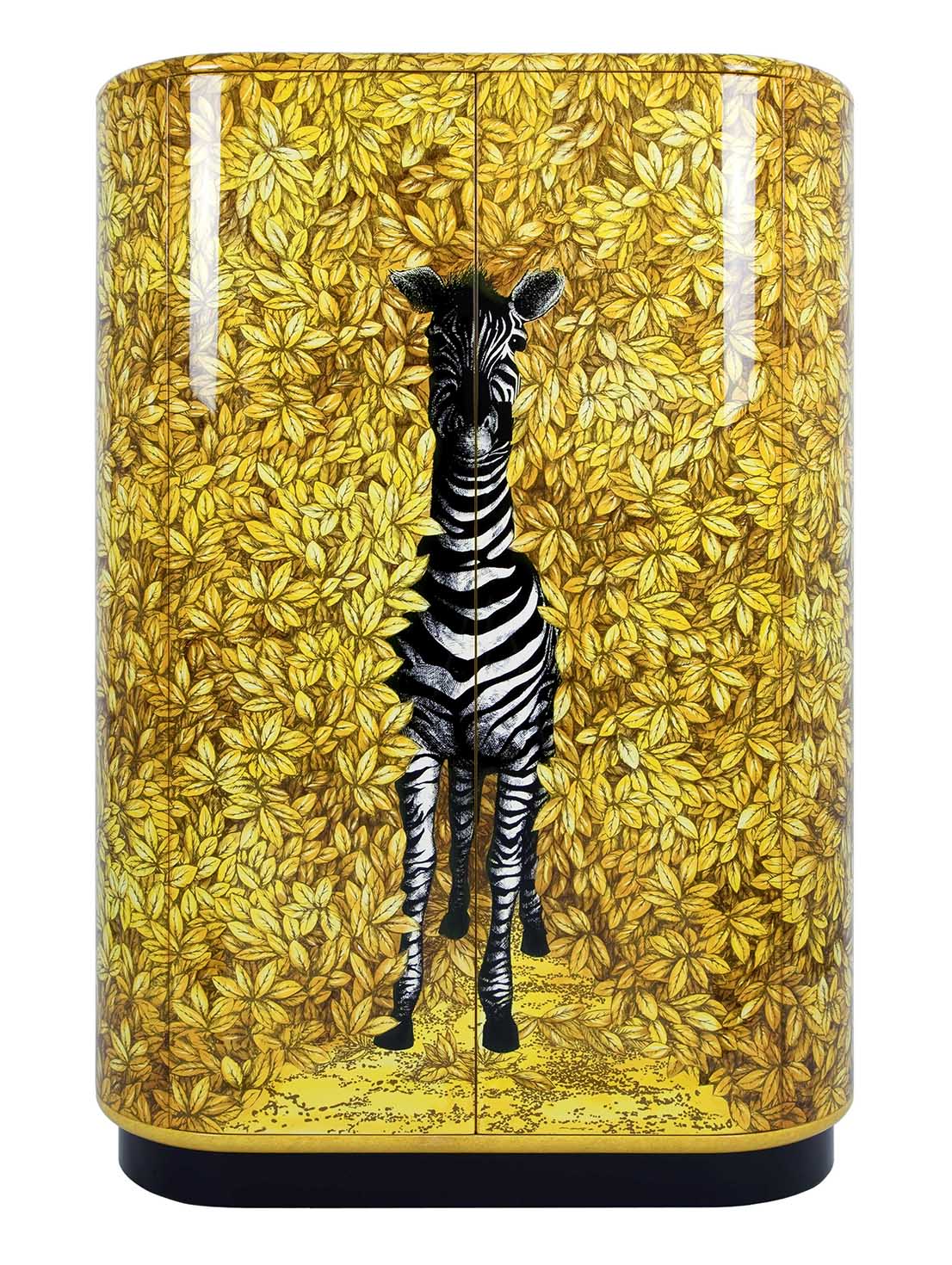

Zebra, design by Barnaba Fornasetti, 2003.

Silviasub, design by Barnaba Fornasetti, 2014.

Egocentrismo, design by Barnaba Fornasetti, 2005.

Kiss, design by Barnaba Fornasetti, 2006.

Barnaba Fornasetti. Photo: Giovanni Gastel and Ugo Mulas.