15 November 2017

It doesn’t seem a good time to invest in renewable sources of energy. From the White House, the president of the United States, Donald Trump, has recently launched a series of initiatives that threaten to undermine the spread of wind and solar power in the world’s largest economy. From the cabinet, the Secretary of Energy, Rick Perry, is using all the legal and legislative means at his disposal to keep Trump’s electoral promise of leaving as many coal-fired power stations in operation as possible. In Congress, the new tax plan proposed by the president calls for cuts in funding and incentives for clean energy. And in the corridors of the White House there are rumors of a series of tariffs to be imposed on photovoltaic panels imported from overseas, which certainly will not favor competition and the spread of the technology. In short, the time in which there was hopeful talk of clean energy as a perfect marriage of idealism and profit, and of the so-called green economy as the business that would allow us to save the planet without slowing the engines of the economy, seems over. But while renewable energies might appear to have gone out of fashion, it is not so. On the contrary: there is no better moment than this to take an interest in the green economy.

Just as in geopolitics, every crisis and every power vacuum generates new opportunities and new leaders, and thus the sector of the green economy is, if anything, richer in possibilities than it has ever been before—for Italy too, which has what it takes to be a driving force in a sphere in which it was slow to get off the mark but has great potential. Despite the ill omens of the last few months, all the figures show that 2016 was a golden year for renewable energy—and 2017 looks like surpassing it. In a mammoth inquiry published in May, the City of London’s newspaper, the Financial Times, announced that the 21st century is likely to be last one reliant on fossil fuels. This does not seem to be anything to cheer about, you will say: there are another eighty years to go. In reality, when we are talking about sources of energy, momentous changes take decades and sometimes centuries, as with the passage from a world fueled with wood to a world dependent on oil in the 19th century. And with the pace at which renewable sources were being adopted up until a few years ago, many analysts feared that the old fossil fuels would still be in use in 2100. But in recent years much has changed, and now there is a bit more confidence in this respect.

The Financial Times had something else interesting to say. For the first time, the British newspaper assigned a capacity for “disruption” to the green economy and renewable energy. The term, widely used in the tech industry, applies to all those companies that, thanks to a surplus of innovation, talent and grit, are able to supplant obsolete industries and technologies. To give you an idea: Uber is—or rather, would like to be—the “disruptor” of taxi services. Now, up until a short time ago, renewable sources of energy were anything but “disruptive.” On the contrary, they were so uncompetitive that they needed substantial and expensive state subsidies in order to have any hope of holding their own in the market. Over the last twenty years, Germany has become a world leader in the field of renewable energy in just this way: by asking its willing taxpayers to fill the gap in competitiveness and cost between renewable and fossil fuels. It was a farsighted policy, because Berlin is now in pole position to take advantage of a booming market, but things are now changing. The competitiveness, efficiency and affordability of wind, hydroelectric and solar power are rising at a much faster pace than state subsidies are being cut, and a new era has begun in which the rate of adoption of the new sources of energy can take a definitive step up, forcing traditional industries to modernize, introducing new players and becoming a fundamental locomotive of innovation.

We see it every day, even on the news: the great emphasis placed by business and the media on the development of efficient electric cars at a price affordable to the general public, something that has passed from a niche market to a mainstream trend (we will be returning to this shortly), and this tells us that the transition from fossil fuels to electricity is real. In Manhattan (while certainly not an accurate reflection of the rest of the world, it can be taken as a trendsetter), there are already more charging stations for Tesla electric cars than gas pumps. The leading players in the oil industry have now been forced to take note. As the Financial Times pointed out, Saudi Aramco has spoken of a “global transformation” brought about by renewable energy; Royal Dutch Shell has said that the revolution is now “unstoppable”; and in October the French company Total announced that by 2035 at least 20 percent of its energy portfolio would be made up of wind, solar, biogas and biomass projects (we will return to this too, and see that some are doing even better).

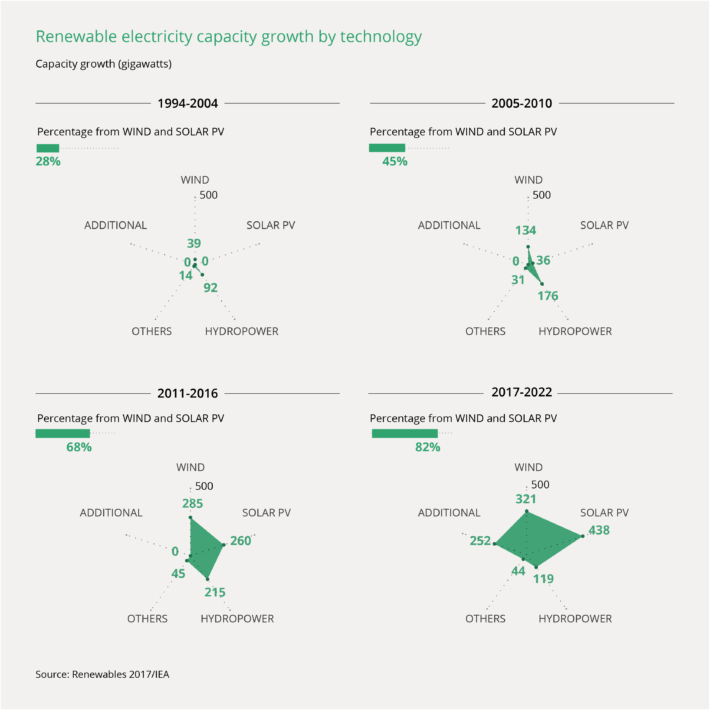

But let’s start with the figures. For this we can draw on the latest report on renewables by the International Energy Agency (IEA), published on October 4 of this year. The attitude of the agency itself is indicative of how things are changing. Just five years ago, in its World Energy Outlook, the IEA suggested we were entering the golden age of natural gas. Today, in its October report, it is predicting a “bright future” for renewables and a “new era” for the development of solar energy. In 2016, the production of energy from renewable sources rose by 9 percent and renewables, with solar power at their head, were responsible for two thirds of all the world’s new energy capacity brought online over the course of the year: almost 165 gigawatts, largely thanks to a 50 percent growth in photovoltaics. According to the IEA, between now and 2022 electricity capacity is forecast to expand by another 43 percent, and the figure is an interesting one because just a year ago the same report spoke of an increase of around 30 percent: 12 months have been enough to make the agency revise its predictions drastically, so that it is now convinced that by 2022 renewables will have a 30 percent share of the energy market.

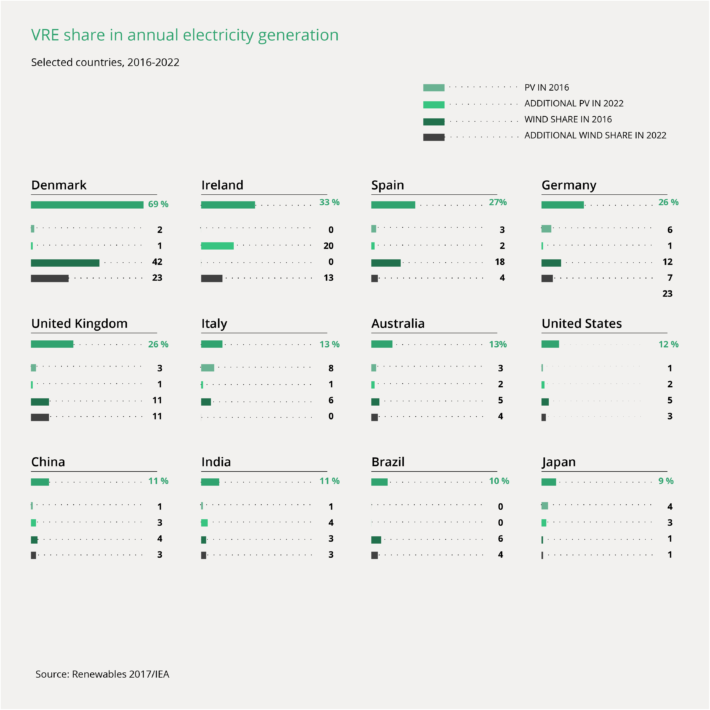

This revolution has an obvious new trailblazer, and it is China, which by itself is responsible for 40 percent of the world’s production of renewable energy today and is destined to remain the undisputed leader in the sector for at least a decade—but watch out for India, which the IEA forecasts by 2022 will be producing as much clean energy as the United States or the entire European Union do today. China has made the development of renewable energy sources an economic imperative and the reduction in levels of smog, a grave problem for its citizens, a political priority. The Communist Party Congress that came to a close in October confirmed that the government sees renewable energy as the key to solving the great contradiction that lies at the base of the Chinese model of growth. But China dominance is not just quantitative. Six of the world’s ten biggest manufacturers of solar panels and four of the ten main manufacturers of wind turbines are in China. Chinese mass production has helped to lower the costs of these technologies substantially: not only for wind turbines and photovoltaic panels, but also for high-capacity batteries, needed for storage of the energy produced.

Other technologies are on the verge of becoming mainstream and might be capable of giving renewables a boost toward a definitive seal of approval. When, last April, for the first time in history a manufacturer of electric cars, Tesla, overtook General Motors to become the automaker with the largest market capitalization in the US, it became clear to everyone that something was changing—and it matters little if GM later recovered its primacy: something symbolic had occurred. Here too China is making a notable contribution, not just because, following the example of the United Kingdom and France, Beijing announced this year that it was going to ban the sale of vehicles powered by fossil fuels by 2030, but also because through an intelligent policy of aid, subsidies and works of infrastructure the government is preparing for the biggest market for automobiles in the world to become completely electric, thanks to the promotion of environmentally friendly cars, the construction of a widespread network of charging stations and, as we have seen, the large-scale production of clean electrical energy.

It is true that for the moment most of the electric power consumed by China comes from fossil fuels (almost 90 percent), and in particular from anything but clean coal. This is why the case of the American company Tesla is especially interesting. Its founder Elon Musk, in fact, has focused on the complete package. Not only does it produce electric cars with a performance that matches gasoline-powered ones, but it also makes photovoltaic panels and “giga” batteries able to meet the energy needs of a home. In short, some people are already planning entire life styles around renewable energy.

And here we come to Italy. If the European leader in the production of renewable energy is Germany, and the leader in the world is China, Italy still has a long way to go, and yet it has a lot of which it can be proud. Between 2004 and 2013 the production of energy from renewable sources tripled, and the country has met its goal of producing 17 percent of its energy from such sources by 2020 ahead of time. It seems that the political objective of the new National Energy Strategy now being drawn up by the government is to put an end to the production of energy from coal by 2025.

In this sense, a company that stands out for its own strategy on renewables is Edison. The utility, which has always been a leader in the energy and in particular the electricity sector, has recently announced that it intends to raise the proportion of energy from renewable sources in its own production mix from the current 20 percent to 40 percent by 2030. “After the Paris Climate Conference, EDF (the company that controls Edison, author’s note) launched a program for the development of renewable and low-carbon sources,” Marco Stangalino, director of Edison’s hydroelectric and renewable sources sector, tells Klat. At the moment of the presentation of Edison’s new strategy for renewables, the company’s CEO Marc Benayoun announced a plan for the investment of a billion euros over the three years from 2017 to 2020 in Italy alone, two thirds of which will be allocated to renewable sources.

Aerial view of the Venina Dam, in Valtellina, in July 2013. Photo: Andrea Siri / e-motion s.r.l. © Edison Spa.

Edison’s strategy has two strands of development, hydroelectric and wind. The former is a historic sector for Edison. “The company was the first to construct a hydroelectric power station in Europe,” says Stangalino, referring to the famous Bertini plant on the Adda River, dating from 1898. “Hydroelectric assets are the history of the group and are one of the areas of future growth in the renewables sector.” Following an operation of renovation of its existing plant, Edison has focused on an interesting strategy, based on sustainability: that of small hydro. In addition to maintaining the efficiency of the large-scale plant it has built in the past, Edison has concentrated on smaller facilities scattered around the territory, with a lower impact on the environment, a more constant output of power and a simpler process of authorization. “The development of large-scale plant has already been done and now is the moment to exploit the potential of smaller facilities located along rivers,” comments Stangalino. Over the last few months, Edison has acquired small hydro plants all over the country, with the takeover of Frendy Energy, a Tuscan company that runs 15 small plants in Piedmont and Lombardy. The jewel in the crown was a plant that recently started up on the Adda, where it all began. The small hydro at Pizzighettone produces renewable energy for 6000 families and avoids the emission of 8000 metric tons of carbon dioxide into the air a year.

In the wind sector, Edison aims to become the leading producer in Italy. The company has 38 farms in various parts of the country, and this year has started to build four more (two in Campania, one in Sicily, one in Basilicata), as a result of the good result achieved in the last wind power auction held by the GSE (Gestore dei Servizi Energetici). Through E2i Energie Speciali, a company set up in 2014 in partnership with F2i (the private equity firm that manages infrastructure funding, translator’s note), Edison has gained an additional 153 MW of wind power on top of the 600 MW that were already part of E2i’s portfolio. In the wind sector, in part due to the aforementioned reduction in incentives, economy of scale is important. Size is needed in order to be sustainable, but the Italian market for wind energy is fairly fragmented. Of the 9 GW of total installed capacity, the biggest Italian operator possesses only 1.1.

General view of the dam on Lake Publino and reservoir of the Publino plant, in Valtellina, in July 2013. Photo: Andrea Siri / e-motion s.r.l. © Edison Spa.

Thus Edison’s strategy for both hydroelectric and wind power can be summed up in two words: build & buy. The meaning is simple: the company needs to build new plant, like the one at Pizzighettone, and to buy others, strengthening its position in the market and contributing to decarbonization. The turning point for sources of renewable energy, as we have seen, is when they start to become “disruptive,” i.e. when, in addition to the weight of investment, the development of clean energy begins to bring with it an irresistible pressure for innovation. Italy is reaching this stage. A tad late, perhaps, but it’s getting there, and there are good reasons to be optimistic. From Edison downward, a handful of companies are ready for phase two, the one in which clean energy will not just be a necessary environmental duty, but an unstoppable force capable of changing the lifestyle of us all for the better.

Wind turbines at sunset, at the San Francesco di Melissa-Strongoli Wind Farm (Crotone). Photo: Renato Cerisola. © Edison Spa.

General view of the Scais Dam, part of the Vedello hydroelectric plant, in Valtellina, in July 2013. Photo: Andrea Siri / e-motion s.r.l. © Edison Spa.