30 July 2014

Italian Limes is a research project and installation presented at the 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture that opened on June 7 and will remain on show to the public until November 23. This post is the first in a series of analyses that will set out to expand on the themes of research that underpin the project over the coming months, outlining possible developments and presenting new material not included in the exhibition.

“There are more international borders in the world today than ever there were before.” These are the opening words of the book A Companion to Border Studies by Thomas M. Wilson and Hastings Donnan, one of the most recent and important publications in a new field of research at the intersection between geography, anthropology and political science. It is a statement that places the accent on a fact often overshadowed by all the contemporary talk of global markets and hyper-connectivity: although the process of digitization currently underway has removed many physical constraints on our everyday lives, we inhabit a world still bound by the 19th-century logic of national institutions and their principle of sovereignty. The struggle for territorial independence remains a priority for any minority, rooted in the belief that recognition by the international community requires, in the first place, the definition of a boundary marking out an inviolable portion of land.

When we were asked to come up with a proposal for Monditalia (one of the three sections of the Architecture Biennale this year, focusing on Italy as a key to understanding the contemporary condition of the globe), we decided to explore the changes that the border of the state—as a formal institution—has undergone since the signing of the Schengen Agreement in 1995. The act of crossing a border—which used to be one of the most vivid of the experiences through which people recognized themselves as part of a national community—has gradually disappeared within the European Union. Over the course of the last twenty years almost every physical trace of the frontier has melted away (take a look at the Polish photographer Josef Schulz’s beautiful project on the abandoned border posts of Europe). Today, for a citizen of the West, the very notion of border has become an abstract concept, linked to the representation and memory of a line on a map. Italy’s land border, however, is still a very strong visual boundary: the arc of the Alps is a natural barrier that gives Italy its highly recognizable profile—as well as creating a marked territorial discontinuity with the rest of the continent. In addition, the frontiers that run through the Alps have undergone notable changes in their role and their nature. Up until the end of the last century, they defined a broad spectrum of international relations: from the friendly ties with France and Austria (NATO allies) to mediation with the economic and political enclave of Switzerland and the tightly sealed border with the former Yugoslavia—de facto, the southernmost edge of the Iron Curtain. This scenario, today, seems to be a forgotten landscape, covered with the dust of the past.

Demolition of the last stretch of the boundary fence in Gorizia, at the time Slovenia joined the European Union, in 2004. From the archives of the Istituto Geografico Militare.

What interested us, too, was to look at what it is that makes a border, from a physical as well as a legal point of view. How do we recognize it, when we cross it? Are there substantial differences between natural and artificial borders? To what extent is a borderland affected by its position on the edge? And last but not least, we wanted to examine the peculiarly European character of the Alps: despite resembling a great park set in the midst of an enormous polycentric city—which is what Europe has become today—the mountain range is still a territory formally divided between eight different nations. Taking these as our premises, we began our research, looking first of all at how a region that was for a long time one of the main theaters of the continent’s geopolitics has now been reduced to a field in which mere economic forces are at work. Losing their role as filters of political and cultural mediation, the mountain passes have evolved into simple infrastructural channels, controlled by European regulations, market performance and logistical standards. At the same time, the natural ecosystem has been turned into a vast theme park that makes huge seasonal profits. Against the backdrop of this varied landscape, the Alpine peaks bear witness to a still distinctly present division—although a silent and almost invisible one—amongst a multitude of local authorities and models of governance.

The Italian border runs for almost 2000 km from Muggia, near Trieste, to Ventimiglia, at the western end of Liguria. It follows the line of the watershed, or drainage divide, that separates the adjacent drainage basins through the whole arc of the Alps. The state border is defined and maintained by the Istituto Geografico Militare (IGM), the national mapping agency which has been based in Florence since 1865 and is part of the army. Its course derives to a great extent from the provisions of the Treaty of Peace with Italy, signed in 1947 after the end of the Second World War. Its short history reflects many facets of political developments in 20th-century Europe. While the border between Italy and Switzerland has not undergone great changes since the beginning of the 19th century, the one between Italy and Austria was extensively redrawn by the battles of the First World War and the one with France was altered by a number of “minor” territorial cessions at the end of the 1940s following the defeat of Fascist Italy in the war. With regard to the French section, it is interesting to note that one of the few boundary disputes still unsettled in Europe is the one over the summit of Mont Blanc, which France considers to lie entirely in its territory, whereas for the Italians it is part of the watershed, and therefore exactly on the borderline. The frontier with Slovenia, finally, is in fact the same as the one that separated Italy and Yugoslavia after 1954, the year when the Free Territory of Trieste ceased to exist.

At a certain point in the research we came across an apparently marginal piece of information, an exception to the routine of the diplomatic relations between neighboring states. As a result of global warming and the consequent—and now constant—retreat of the Alpine glaciers, the watershed—which runs along perennial glaciers at the highest altitudes—has shifted considerably in recent years. So between 2008 and 2009 the Italian government had to negotiate a new definition of the frontier with Austria, France and Switzerland, introducing into national law the unprecedented concept of a mobile border and thus negating the possibility of determining its own boundaries with certainty. Every two years a special commission, made up half of experts from the IGM and half of representatives of the cartographic institutes of the bordering countries, retraces the entire course of the state border. In addition to maintaining the boundary markers with which it is dotted, the aim is to determine, with the aid of high-precision GPS trackers, the shifts in the surface of the ice and calculate the exact position of the watershed, in order to establish the new borderline.

Members of the team working on the maintenance of markers on the state border and the determination of their coordinates using GPS technology. Gran Mesule peak (3749 m), Italian-Austrian border. Photo by Simone Bartolini, July 2006.

This story—apparently of no relevance to our daily lives—immediately prompted a broader reflection on the dynamics of contemporary geopolitics. It highlights the provisional nature of any boundary condition, the fact that natural frontiers are subject to changes brought about by environmental processes and, finally, how technology influences the way we think and operate at every level today. The most remote areas of the Alps—so inaccessible that they were regarded, up until the beginning of the last century, as terra incognita—have been the proving ground for a constant advance in the technological means of representing the territory. The need to measure accurately the borders between Italy and other European nations led first to the invention of photogrammetry in the 19th century, then to campaigns of aerial photography during the First World War and, more recently, the immense task of defining the national trigonometric network. Today, this work of mapping has been made totally invisible by the adoption of GPS technology. At the same time, however, it obliges us to adhere to a completely new level of precision and accuracy, and to define new operating parameters.

Once the objectives of the investigation had been framed, we tried to work out how to create an installation that would be able to communicate the results of the research to visitors to the Biennale. We chose a case study—the Similaun glacier, where the border between Italy and Austria runs for about 1.5 km at an altitude of 3330 m above sea level. The relatively short length of this section of moving border made it possible to measure it in the field, while an earlier interview with the geographers of the IGM had established the fact that the boundary in that position had shifted discernibly. So on May 4, 2014, we reached the surface of the glacier: there, after six hours of work in far from easy conditions (it is still winter in the Alps in early May, at an altitude at which the lack of oxygen takes its toll on the untrained body), we installed five solar-powered GPS units along the borderline determined by the most recent official measurements made by the IGM in the summer of 2012. Once an hour, the GPS sensors transmit their geographical coordinates to a remote server by satellite link.

The solar-powered GPS sensors on the Similaun glacier. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, May 2014.

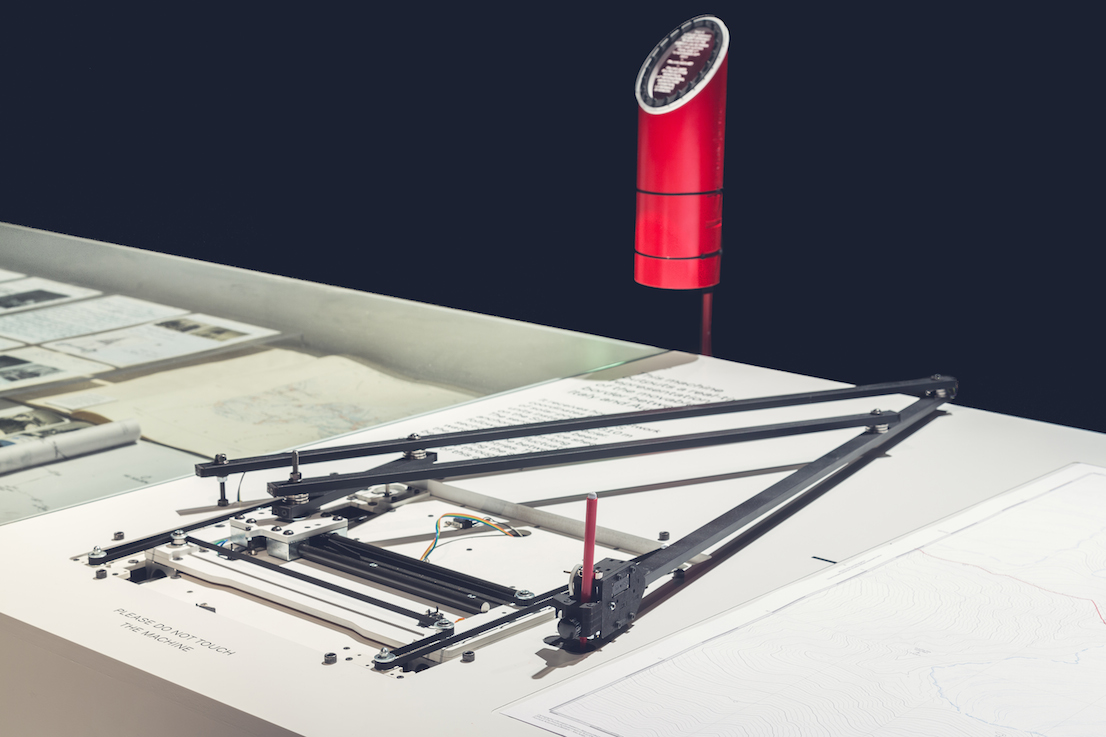

The installation at the Corderie dell’Arsenale is made up of three elements laid out in a line: a three-dimensional model of the summit of the Similaun and the glacier that extends at its foot, to the east; a collection of previously unpublished documents from the archives of the IGM; a drawing machine connected to the net. The model—a reproduction of a portion of the Ötztal Alps on a scale of 1:3000—was made by a CNC milling machine from two blocks of plaster (which were then joined together to reach the full height of the relief) and used as a surface for the projection in three dimensions of an animation based on historical maps of the zone and illustrating the changes in the position of the Italian border with Austria between 1920 and 2012. The IGM documents comprise photographic material, maps and campaign journals that testify to the indefatigable work of the people responsible for maintaining the border and to the evolution in the techniques and instruments used over the course of the last century. The drawing machine—an automated pantograph controlled by an Arduino board and programed with the Processing language—is able to convert in real time the coordinates received from the GPS sensors into a representation of the shifts in the borderline. It functions autonomously and can be activated on request by any visitor, who will therefore be able to take away a map—different on each occasion—of a section of the boundary between Italy and Austria, created at the exact moment of the visit to the installation.

Two months after being anchored to the surface of the glacier—and the printing of about 4000 maps by the pantograph—the GPS trackers continue to monitor the movements of the border on the Similaun. It is now the height of the summer season, during which most of the subsidence of the ice should take place, in conjunction with the melting of the mass of snow that covers the surface for the greater part of the year.

Italian Limes at the Corderie dell’Arsenale. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, June 2014.

Italian Limes at the Corderie dell’Arsenale. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, June 2014.

Italian Limes at the Corderie dell’Arsenale. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, June 2014.

Suggested reading

– Paolo Giaccaria, “Confine → Soglia,” in P. Perulli (ed.), Terra mobile. Atlante della società globale. Turin: Einaudi, 2014;

– Barry Smith and Achille C. Varzi, “Fiat and Bona Fide Boundaries,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 60:2 (2000)

Colophon

Italian Limes is a project curated by Folder (Marco Ferrari, Elisa Pasqual) with Pietro Leoni (interaction design), Delfino Sisto Legnani (photography), Dawid Górny, Alex Rothera, Angelo Semeraro (projection mapping), Alessandro Mason (coordination of production) and Claudia Mainardi.

Italian Limes has received a Special Mention as a research project in the Monditalia section from the jury of the 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture.

Follow Italian Limes on Twitter.