6 April 2016

Nomen est omen. A name, a destiny. When I meet Giovanni Tomaso Muzio in his studio on the Navigli, located in a basement like the one where his father Lorenzo and the illustrious grandfather whose name he bears used to work, it comes to my mind that no one is better suited than he to preserving the legacy of one of the protagonists of Milanese city planning and architecture in the 20th century. For almost twenty years, in fact, Giovanni Tomaso and his mother Mirella Zevi have been running the historical archives that contain the designs produced over the course of his grandfather’s long career, which are also open to researchers. Very Milanese, with a lively air, quick mind and forthright manners (and views), Giovanni Tomaso is a sincere supporter of his grandfather, born in 1893 and the designer of 45 buildings within the circle of Milan’s Spanish Walls. At times he takes on the tone of a defense attorney, called on to represent a complex and dynamic figure.

Don’t you feel you’re exaggerating a little when you speak of a denial of his value or at least a lack of recognition?

Not at all. With the exhibition in 1994 curated by Franco Buzzi Ceriani for the reopening of the Milan Triennale—one of Muzio’s symbolic projects—there was a lot of talk about my grandfather: various articles were published, Vittorio Gregotti called for a more comprehensive and nuanced evaluation of his work and Fulvio Irace brought out a monograph which he said he hoped would revive interest in a neglected architect. Then silence fell. That was the first and last anthological exhibition on Muzio. Since then there has been no sign of any desire to study, investigate or understand him. Even the great names in criticism have snubbed him: Bruno Zevi ignored him and only one of his projects got a mention in Kenneth Frampton’s history of architecture: the Ca’ Brütta.

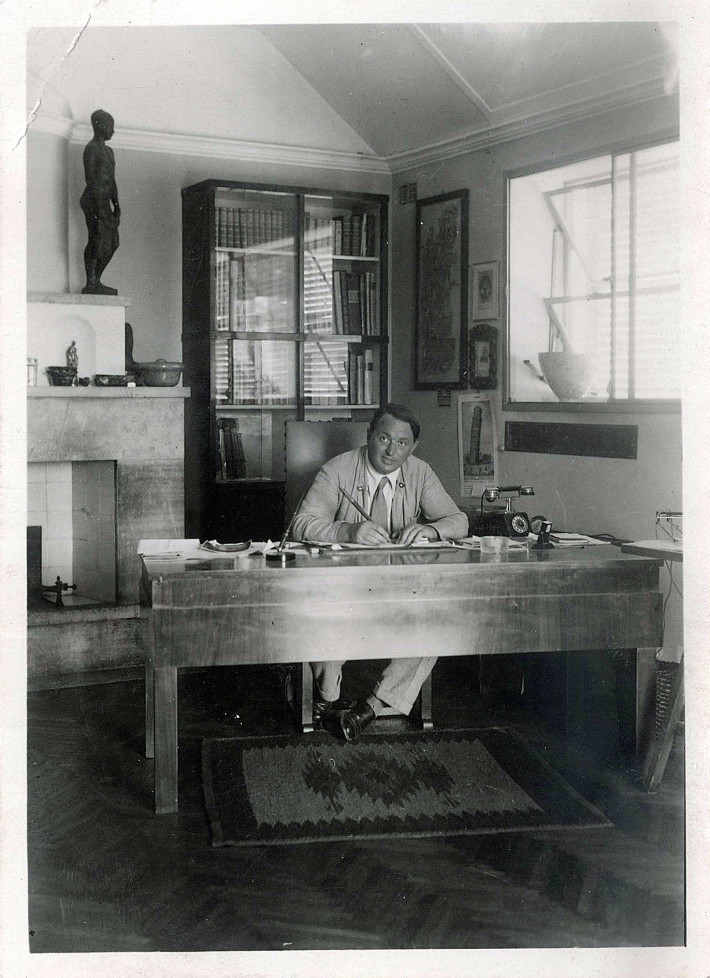

Giovanni Muzio, 1930. Courtesy: Archivio Muzio.

Why do you think this is?

It’s partly because he worked during the twenty years of Fascist rule, a period in history and politics that has long been suppressed, more so in architecture than in art. Those who received their training in the decade following the end of Fascism, in their eighties today, dismissed him for reasons that are not hard to guess. Those who studied in the seventies wanted to look to the new, to the great current of Modernism and the International Style. Then came my generation, born in the sixties, which could have begun to study him again, but limited itself to going back over what had already been done, without undertaking new research. Muzio was a socialist, he believed in architecture as an eminently social art. The period between the wars was an extraordinary one for him. He designed and constructed all of the city’s most representative buildings: the head office of Cariplo, the Palazzo dei Giornali, headquarters of Il Popolo d’Italia, the Palazzo dell’Arte, the Palazzo della Provincia. Muzio had the extraordinary opportunity to design buildings and districts that would leave a mark on the growing city. That period has given a slant, a style to the city. There were many who worked in Milan at that time: not just my grandfather, but also Alpago Novello, Emilio Lancia, Tomaso Buzzi, Gio Ponti, Ferdinando Reggiori and Ottavio Cabiati. Giving them no consideration means being provincial.

Do you find there are still prejudices about the architecture produced under Fascism?

By now they have faded. My grandfather began working in Milan as soon as he got back from the Paris Peace Conference, in November 1919. His first work was a private commission. He was 26 when he joined the Barelli-Colonnese studio. Today the original building in the Moscova district, which so upset his contemporaries that it was nicknamed the Ca’ Brütta, the Ugly House, is seen as a symbol of the dividing line between eclecticism and the modern, for its freedom in the use of plaster and simplification of the façade. It was also the first example in Italy of the splitting of a city block, creating a private road open to the public.

Ca’ Brütta, Milan. Photo: Luca Campigotto.

Ca’ Brütta, a watershed building whose restoration has just been completed, after twenty years.

To the great satisfaction of everyone involved, including myself. In 1992 I became advisor to Ca’ Brütta and, as the person in charge of the Muzio historical archives, was the artistic supervisor of the restoration, which has been in part for the purposes of conservation and in part a matter of reclamation and reintegration. Today the building has been returned to the state it was in in 1922. Over the last four years, I’ve brought up a thousand issues to ensure respect for the original work.

Ca’ Brütta has been the subject of a call-to-action aimed at photographers and an exhibition that will open on April 15 in Milan.

On Instagram we invited everyone to share their photos of buildings designed by my grandfather through a call made on November 18 last, exactly 100 years after Muzio’s graduation with a degree in civil architecture. On display at the Castello Sforzesco, along with the Instagram photos that will introduce the legacy he has left us to non-specialists, there will be original illustrative material that sets the project against its historical background and pictures by well-known photographers who have portrayed the building over the decades and today: pictures taken by Ugo Mulas and Gabriele Basilico, as well as by thirty photographers, from Gianni Berengo Gardin to Giovanni Gastel, who were invited by Giovanna Calvenzi to reinterpret the building and its poetics after the restoration. Reassessing Muzio through his manifesto building and the medium of photography is in my view the best way of looking at them both. My hope is that all this will bring him back into the spotlight.

Ca’ Brütta, Milan. Photo: Francesco Radino.

Why the Castello Sforzesco?

Our marvelous castle is a symbol of the past, and it’s also the only place that people not from Milan immediately associate with the city. My grandfather didn’t like it because it was linked to an idea of restoration that fortunately no longer exists. I like it because there’s something alien about it and it’s popular, like Ca’ Brütta, which is being given back to the city through the work of restoration and this exhibition. It has been interesting to complement, in collaboration with the castle’s conservators, the research on Ca’ Brütta in our archive materials with the documents in the Archivio Storico Civico and Biblioteca Trivulziana, the Civico Archivio Fotografico and the Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Achille Bertarelli.

The professional aspect is very marked in the tone of what you say, but I can also sense an element of family pride. What kind of grandfather was Giovanni Muzio?

He was wonderful. A blunt and forthright man. With him I learned to swim. He threw me in the water and told me to get on with it. Most of the time I had with him was in the summer, when the whole family spent a month together in the house he had designed at Sirmione on Lake Garda. He loved that house and went swimming there all year round. He did so a year before he died, in May 1982. I was 16 at the time.

Ca’ Brütta, Milan. Photo: Maurizio Camagna.

Did he ever talk to you about his work?

He was a self-effacing man and never talked about himself. He invited you to lunch once a week and amused himself teaching you to drink, because for him it made no sense not to try alcohol. It was not until after his death that I discovered much about his work. During my years at university my mother would sometimes show me my grandfather’s buildings as we went around Milan. It was a sort of aesthetic education. I have had the good fortune to always live in beautiful spaces, designed by architects, almost always members of my family. Now I live in a house that was designed by my grandfather, then renovated by my father and finally by me.

A foreordained destiny. There are now four generations of architects in the family. Did they encourage you to carry on with the family name?

Quite the opposite. Both I and my elder brother Sebastiano were strongly advised against it by our architect mother and father. This was in the eighties and the crisis in a profession they had always loved was beginning to make itself felt. We probably decided to do it as an act of rebellion. We’ve never had the impression of being part of a family business that had to be kept going. We just wanted to share images, ideas, a rational way of doing things, the pleasure of finding elements in common over the course of time.

What does practicing this profession mean for you today?

We architects are people who work on commission, rather than prima donnas. We are constructors of spaces intended to meet the requirements of the client and we do so thinking about his future too, clearly seeking to find a balance between rationality and elegance, adding a personal interpretation, a style. Today, however, you get the impression that architecture is no longer viewed as a job. What we see instead is self-promotion, a tendency to hog the limelight, marketing, public relations. The truer and more concrete message of the architectural project has been eclipsed by outward appearances. The focus is on the image and not on a well-studied plan or section. The details of a design ought to be the consequence of an overall logic and way of thinking, not elements that contribute to the creation of a beautiful object which often, in the end, is not able to establish a relationship with its context.

Ca’ Brütta, Milan. Photo: Ray Banhoff.

You are proposing a “return to the fundamentals” of the profession, to the basic elements of design. Fundamentals and Elements of Architecture were the title of starchitect Rem Koolhaas’s 2014 Biennale and his exhibition in the Central Pavilion respectively. Do you see things along similar lines?

I find it paradoxical that an architect like Koolhaas should have shaped his Biennale around these themes. He is an extremely capable professional, very good at the beginning, with a new and comprehensive vision, but his designs do not always fit into the context in which they are set. I didn’t like his Biennale, acclaimed even before it opened. As a professional, it didn’t teach me anything. It gave me the impression that it had started out as a publishing project and then been turned into an exhibition.

So you must have liked Koolhaas’s new Fondazione Prada, which has molded a container for art out of a former distillery that had been turned into a goods warehouse.

I like the area, which has been subjected to major transformations, but I find the project fragmentary, with functional objects, but independent of one another. For now it is a respectful intervention, but they still haven’t built the tower, which will be the crowning piece of the whole project, as well as a powerful visual signal. Probably it’s Koolhaas’s architecture that “doesn’t do it for me,” but I do give the Fondazione Prada credit for carrying out initiatives useful to the city, and doing it for thirty years. In line with what Beatrice Trussardi does with the exhibitions curated by Massimiliano Gioni, which introduce us to precious and hidden places of Milan.

Ca’ Brütta, Milan. Photo: Giovanni Hänninen.

As Muzio’s heir, you can’t fail to be grateful to the Fondazione Prada for having realized the intervention conceived by Dan Flavin for the Chiesa Rossa.

The essentiality, elegance and purity of those spaces made it possible to work with contemporary art and turn a place of worship into one animated by a secular spirituality. Those simple neon lights bring out the tunnel vaults, the apse, the sharp edges in an incredible way. We shouldn’t just put up with the mold of history, but take possession of it. Knowing out history is what helps us live our daily lives.

What do you thing of the cleaning up of the Darsena?

Some things deserved different solutions. The market, for example, could have been treated like one of the great public markets of Europe, and the bridge could have a more contemporary look. But I think that in the new Darsena the individual architectural objects should be put into the shade for once by the enthusiasm with which the city has taken back the area, after having walked for years along the edges of a “spontaneous” park close to a state of absolute decay.

And the interventions at Porta Nuova?

I’m pleased that new area exists, but at the level of city planning I don’t like it. When the last buildings are constructed, the zone will be hyper-saturated. The impact on the Isola district is a violent one, partly because the buildings are viewed singularly, not in relation to the context. I’m happy that Stefano Boeri has won all the awards in this world for the Vertical Forest, whose architecture takes me back to the fifties in Lombardy with its use of vegetation, and which has rightly become a prototype to be exported, with slight differences, to Lausanne. It will be replicated in China too, and can certainly find a home in any part of the world. But overall no work has been done on the urban fabric, which is one of the most difficult things of all. Going into details there are choices I don’t agree with: there was no need, for example, to create a difference in level of 6 meters from Corso Como to Piazza Gae Aulenti. The private sphere stepped in, with money, and a new center has been created, a response to the one that was never conceived and realized in the early fifties. Perhaps such an extraordinary operation would have brought about important, more profound changes, if it had been done in a more peripheral area. Moreover, an enormous residential area has been created for which there was no real necessity, so that the investors, in the end, were foreign funds. Speaking of residential areas, I’m keeping a curious and attentive eye on CityLife, a construction site that is still open and will bring a new and substantial supply of housing onto the market. Milan is small and very simple too. It’s a city where a lot of business is done, but people don’t live there with the same intensity. What I’m trying to say is that those who can afford it won’t put their money into CityLife, but into the historic buildings of the old city.

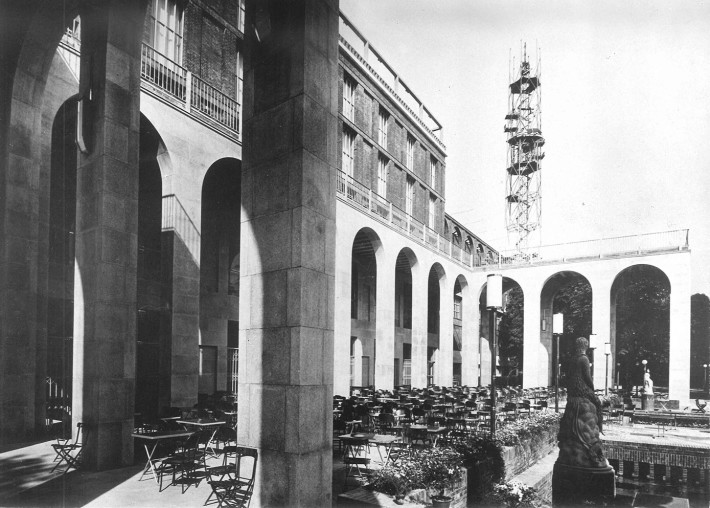

Palazzo dell’Arte, Milan Triennale, 1932. Courtesy: Archivio Muzio.

Can we say that your approach to design is a rather conservative one? In the Muzio mold, in short.

In a sense, yes. The lesson I learned from my grandfather was his relationship with the city. He created constructions that carried weight but were light, which first of all established a relationship with their context. He had been conscious of this necessity since the twenties: in 1924 he founded the Club degli Urbanisti [“City Planners’ Club”] with Giuseppe de Finetti, Alpago Novello and many other colleagues and then took part in the competition for the city plan of Milan in 1926-27, in opposition to the municipal schemes, up until that moment solely in the hands of engineers and technicians. That group wanted to construct a city on a human scale that would be beautiful to look at, attempting to preserve as much of the existing as possible. But Portaluppi and Semenza won, making a clean sweep of the past with a project that gave a green light to speculation. Despite losing, Muzio continued to give his advice, because he always considered himself at the service of the city.

It seems to me that the keyword in your thinking about urban planning is “respect.”

If you live in Italy, one of the major themes is that of working on the built. Perhaps the existing restrictions are too rigid, but the intention is to assert that our cities have a history and cannot be radically changed. Cities will have to change on the inside, becoming increasingly technical, working on the saving of energy, but with the awareness that history is made of their constructions.

Palazzo dell’Arte, Milan Triennale, 1932. Courtesy: Archivio Muzio.

The city is also made up of outlying districts, to which Renzo Piano’s G124 work group has recently drawn attention.

An admirable initiative, but we should not forget that the outskirts are not just a matter of regeneration. They need to be planned, or re-planned, inserting points of attraction, otherwise there will just be ghettoization on the French model, whose results we are all too well aware of. I don’t want to sound like I’m always beating the drum for my grandfather, but I would like to point out that in the forties and fifties he planned in Milan—on Via Aicardo, behind Viale Tibaldi—a working-class district with houses, a church and schools for the employees of SAFFA. That’s how to construct a city.

Milan has grown a lot in recent years, with new residential areas, but it has also “cleaned itself up” in view of Expo 2015. How do you assess the results of the World’s Fair in relation to the city?

It’s first merit has been that of having allowed the people of Lombardy, Piedmont and the Veneto—Italians accounted for the majority of visitors to the Expo—to get to know the city. Today, however, the format of the World’s Fair no longer makes sense, at least architecturally speaking, as it does not leave beautiful objects behind—as it did in the nineties at Seville, in Spain, at the time when I was working in Fernando Távora’s studio, and then in Lisbon, where it provided a new connection with the Tagus River. The Expo has become an island outside the city, a marvelous popular festival, and nothing more. A far cry from the original plan of the advisory board of architects—including Ricky Burdett, Herzog & de Meuron and Stefano Boeri—which called for an axis of parkland that that would run from the site of the fair into the city, with insubstantial and minimal structures, touching the nerve centers of culture, including Muzio’s Triennale, which instead remained isolated from the system in those six months, notwithstanding Germano Celant’s mega-exhibition.

Swimming pool of the Tennis Club Milano, Via G. Arimondi, 15. Courtesy: Archivio Muzio.

Was there one of the pavilions at least that you liked?

Michele De Lucchi’s Pavilion Zero, which I thought very closely linked to his own history and seemed to me to be a citation similar to the one that Luigi Caccia Dominioni produced for Piazza San Babila in the mid-nineties.

After the Expo, the 21st Triennale will be speaking of architecture and the city.

Its unusual step of working in many different locations could be interesting, if it is able to connect them all up, otherwise they will become separate islands. It’s necessary to find the right attractions. Involving the university was an excellent idea. It would be great if it turned into a many-voiced event, not too intellectual but not too popular either, like the Expo. The Triennale today is very strong on product design, thanks to the workgroup linked to Silvana Annicchiarico and the Design Museum, which is always active. It’s not so strong on architecture: I don’t recall any exhibitions that I found interesting, not even the most recent one curated by Alberto Ferlenga and Marco Biraghi, Comunità Italia, which lasted for three months, perhaps tried to show too much and so didn’t leave me with a great deal.

Your exhibition will open on April 15 and run concurrently with the Triennale, for three months, but it is not on the circuit of the event.

The exhibition is not just being hosted by the Castello, but stems from a collaboration with the archives of the Castello and is part of the municipality of Milan’s cultural program, Returns to the Future. Like all the events of Returns to the Future, it complements the city’s cultural schedule over the coming months. I like the idea that this small exhibition which concentrates on a single historic building represents an opportunity to get to know Milan better: that is, to come out of the Castello, move on to the Triennale and then rediscover the city and its architecture. During the exhibition we will be organizing numerous guided tours with the Architects’ Association and the Polytechnic, and we have created a popup map. An invitation to stroll around Muzio’s Milan.

Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Milan, 1929. Courtesy: Archivio Muzio.

The Triennale is also one of the city’s symbolic buildings. What do you think of the recent addition of the external ticket office designed by Italo Rota?

It’s a design that’s an end in itself. Rota is an internationally known architect, he had no need to try to boost his reputation in this context too. He could have done something light and they could have removed it on the last day of the Expo: I would have found that much more ethical. They could demolish it, but it would be too costly an undertaking and I’m afraid they won’t do it. Crazy things have happened in the Triennale over the years. In the sixties, the impluvium and the courtyard, which were the source of natural light, were roofed over. The reinforced-concrete staircase built in the courtyard, for example, was only demolished in 2010, when Michele De Lucchi arrived with his project of the Design Museum, which entailed the creation of new offices. On the other hand I’m enthusiastic about the restaurant built on the terrace. A good design, as well as the right way to bring a museum to life in a cosmopolitan city.

I seem to get the feeling you believe in the power of frank criticism, a rare quality in the world of architecture.

Everything is driven by small lobbies of friends. The current attitude is one of agreement or silence. Even the conferences are to some extent ends in themselves: everyone prepares a talk and gives it to a neutral audience. They could easily be replaced by written texts and nothing would change. There is little debate or desire for confrontation, even in the architecture magazines, which in theory would be the best place for criticism. There is no longer any attention to civic questions. Everyone is in a hurry and there is a widespread superficiality. Things pass by, no one notices anything. Perhaps it is partly for this reason that great iconic objects are all the rage and no one stops to look at the structural details and the relationship with the city.

Let’s end with an idea for Milan, something to enhance it in the eyes of those who live in the city and those who visit it.

Easy: a museum of the city. Milan has the greatest concentration of private archives of architecture and design, and it would be only right to have a place to house them. I find that today there is an awareness of how important the city is at the level of trade, but not the intelligence to make use of its own constructions. In this imaginary place it would be possible to tell stories, weaving them around individual buildings, involving archives and interested foundations, to construct a sort of visual and documentary database. It would be an easy format and require minimal investment.

Giovanni Muzio, 1980. Photo: Gabriele Basilico.