13 November 2017

Franco Albini still lives in a typical building dating from the early 20th century, in the Monti district of Milan. To find him, all you have to do is pass through the short portico with columns at the entrance of Via Telesio 13, original location of the studio where he worked with Franca Helg from 1963 onward, and immerse yourself in his archives: around 22,000 drawings, over 6000 contemporary photos and 2500 slides, models, writings, letters, technical reports, books and magazines. From 1929 to the present day. It is the property of the Fondazione Albini, set up ten years ago to promote the working method and ideas of one of the greatest figures in modern Italian architecture—who died almost exactly forty years ago, on November 1, 1977. But there is not just history between these walls. It is also the workplace of his son Marco and grandson Francesco, who have picked up the baton of the “honest and ethical” approach to design professed by an architect who preferred to be called a craftsman. It is Francesco who opens the door of this sacred site of rationalism for me. Forty-seven, a lean build and courteous manners, attentive gaze and measured words. Looking at him, you are immediately reminded of his famous grandfather, a slender figure with an elegant bearing, described as a quiet, reserved and stern man. Only the moustache is missing. I tell him so almost at once, after we sit down in one of the rooms of the foundation, the realm of his sister Paola.

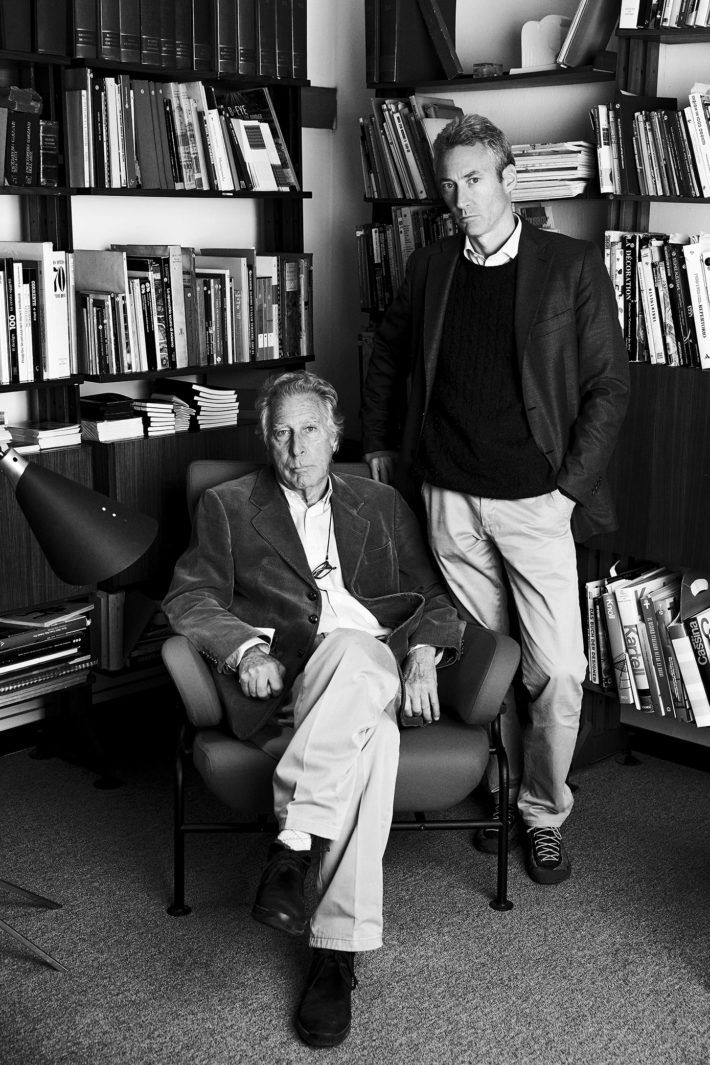

Marco and Francesco Albini, Milan, 2000. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

I can’t have been the first person to notice the similarities.

You’re not the first, it’s true. I became aware of it at an advanced stage of my life. I’ve never tried to emulate him, neither professionally nor at a personal level. It all came a bit at a time. I was seven when he died and don’t have many memories of him. I know for sure that he was not very expansive, a man of few words. My father, who worked with him from the age of thirty, has told me about long car journeys on which he never opened his mouth: he stayed rapt in his thoughts. He describes him as a figure of the utmost integrity, inflexible, but not as severe as some would have you believe. He never forced a choice on anyone, either in the family or at work. He was very respectful of everyone. One of his assistants says that he never interfered in the drawings, expressed no judgments. At the most he would make a note in a corner and ask you why you had acted in that way.

It was enough for him to know the reasons for the choice.

It seems that his “whys?,” his perché? pronounced with a rolling r, were a recurrent note in the studio, a mantra that people then used to mimic him.

Let’s carry on with the whys. Why did you choose to become an architect?

When the time came to decide what I should study I wasn’t clear about what to do. Then I made a list of what I might enjoy and I realized that architecture had a creative as well as a rational side, both of which were potentially interesting aspects, and so I gave it a go.

Franco, Marco and Francesco Albini, c. 1973. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

You didn’t feel the weight of family tradition?

I didn’t feel either favored or disadvantaged by my surname. I think that people are more interested in facts than in names today, more so than in the past anyway.

Your grandfather was a keen skier and I’ve heard that you too love the mountains.

I developed my passion for climbing, which is practically a second job for me, after the one for tennis, by way of skiing. A late inheritance.

Another curious characteristic of your grandfather is that he never owned a house. He always lived in rented accommodation.

He was convinced that property enslaves us, something with which I agree wholeheartedly. I don’t want to have too many ties, too many things to manage.

Do you have memories of his home?

Many of the one on Via De Grassi, a side street of Via De Togni. It’s also the last place I saw him: the image of him sick in bed, the day before he died, is carved into my brain. My grandmother went on living in that house even without him, only on a different floor.

This is an important year of anniversaries: Franco Albini died on November 1 forty years ago and the Fondazione Albini was set up ten years ago. To celebrate his genius, the foundation has organized many events throughout 2017.

The activity of the foundation, which is run by my sister Paola, is aimed at making people aware of a legacy, a way of thinking, a manner of working. An archive like this cannot and most not gather dust. For this reason the program of initiatives for 2017 has been given the title The Sign between Yesterday and Tomorrow. My grandfather lived at a time in which there was a great deal to do. The language of modernity was emerging, driven by a deep-seated ethics. He idea was that his profession was at the service of society. Rationalism reduced everything to the essentials, it implied a profoundly moral attitude that I find very relevant to the present, seeing that we are going through a moment of loss of the sense of community.

Marco and Franco Albini in the Albini home, Via Aristide de Togni, Milan, 1959. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

What was the spirit of these events?

To try to convey Albini’s style and mindset to people utilizing different languages and broadening the target. The foundation has held, for example, a competition of graphic design for the very young that had the objective of coming up with a logo to mark the ten years of its existence that could be used alongside the one designed by Bob Noorda; it has organized workshops to make children aware of the origin of his designs and the value of curiosity; it has staged the show Il coraggio del proprio tempo, conceived by Paola and based on letters that Giuseppe Pagano wrote from the concentration camp, and another one devoted to Franca Helg, a great symbol of female emancipation; it has put on an exhibition of the photos he took on his travels, and other things as well. The program came to a close at the Triennale, in mid-October, with an event offering a foretaste of the activities in 2018. Finally we presented the documentary Franco Albini—Uno sguardo leggero at the Milan Design Festival, which was then broadcast on Sky Art between the end of October and the beginning of November.

Franco Albini argued that talent lay in doing things, rather than in formulating theories: “It is more through our works that we spread ideas than through ourselves.” Which of your works do you think expresses your vision best?

The design of the new Rolex logistics and operations center in Milan. Originally we were going to renovate the buildings of the former Turati Lombardi factory dating from the 1950s, but feasibility studies showed it wasn’t worth it, there would have been too many functional problems. So we knocked everything down and built again from scratch, revising both the internal arrangement and the functions while maintaining the profile of the two original volumes, one slightly staggered with respect to the other: it was the only constraint imposed by the city plan.

New Rolex logistics center, Milan. Design Studio Albini Associati, 2016.

Passing through Viale Filippetti you certainly don’t think you are in front of a factory. The façade is ultramodern, all glass and steel.

We started from the function. Two of the three floors above ground house the workshops, where the primary need is to have perfect control of the natural light, fundamental for the meticulous work of watch repairers. We opted for a double skin of laminated glass: an internal layer that performs the function of thermal insulation and soundproofing and an external one of motorized vertical louvers that change their angle with the movement of the sun and that, if fire should break out, open to let out the smoke. It is a very complex and unique system that took a year of testing. The element that symbolizes the identity of Rolex, the steel, is sandwiched between the two layers of glass that form the sunshades: it is a one-millimeter-thick microperforated sheet that does not block the view of the outside. Thus the steel remains a living, glittering material, with no need for maintenance. Even the system used to fix the panels is customized: we used ball joints, but perforating only the inner layer of glass in order not to give the façade too heavy an appearance, given that we had 1000 panels of 4 meters in height and 30 cm in width, set very close together.

A rationalized work of craftsmanship, in the Albini style.

With the addition of a spectacular and functional side: at night lights, some of them colored, are lit inside this double skin and microperforated drapes descend automatically to protect the interior, preserving the privacy of the place.

Entrance hall of the new Rolex center, Milan, with Tre Pezzi armchairs designed by Franco Albini and Franca Helg. Design Studio Albini Associati, 2016.

How much of a part does the study of materials play in your work?

It has always been important. Even for a project of reclamation and restoration of a historic work of architecture like the monastery in Cairate we carried out a lot of experiments in order to create beams of laminated glass that would not make the structure too heavy. Where the elements needed for reconstruction were lacking, we designed a glass volume in a more modern style, with larch bris-soleil through which the old walls of the cloister can still be seen. These were all elements studied in collaboration with specialists in their execution.

Your view of the architect’s profession is a very pragmatic one.

If you don’t have the technical means, you can talk a lot, but you don’t get very far. Perhaps this is partly why I really enjoyed working, after I graduated, for Renzo Piano, who has chosen to call his studio a building workshop, the RPBW. A workshop is like a laboratory where you do research, you work by trial and error. I’ve always been interested in the study of details and technologies, in order to investigate the individual elements that make up architecture: every building consists of many pieces that are meticulously designed and assembled. This was Albini’s method: to break down the project, study its components and put them all back together in an innovative form consistent with its function.

Detail of the motorized glass-and-steel louvers, new Rolex logistics center, Milan. Design Studio Albini Associati, 2016.

What did you do work on with Piano?

On the reclamation of the Potsdamer Platz area in Berlin and an exhibition on his work in Genoa. I was an intern, perhaps the best position in which to learn a lot without having too many responsibilities.

Piano was also a pupil of your grandfather.

He worked right here in this studio and remembers this first experience of his as giving him a solid grounding as far as typology and working method were concerned.

You encountered him again, virtually, in the competition for the redevelopment of the areas of the former marine trade fair in Genoa, with Jean Nouvel’s gigantic pavilions, that was based on a master plan drawn up by Piano.

We wanted to rejoin the seafront, which had been lost, to the city, overcoming the interruption caused by the rampart along Corso Marconi with a footbridge that would connect up with the roofs of the new buildings that were the subject of the competition. From there we would have gone down toward the sea, where the commercial activities and services for residents and for boating were located. The flat roofs of the new buildings would have become a new urban public space, with vegetable and flower gardens and refreshment points. I have to use the conditional because it was an Italian-style competition with no winner. It was a way of doing research, however. It may be of use to us in the future.

Other architects whose work you admire?

Those who show respect for the context in which they insert their buildings like Kengo Kuma, or who produce sober projects like SANAA and their Rolex Learning Center. In other words architects who don’t impose a work of sculpture that is an end in itself and incapable of establishing a harmonious relationship with its surroundings.

What marks would you give CityLife?

I’d fail it. It was a purely speculative operation with out-of-scale residential buildings, absurd heights for the context. Volumes set so close together, at some points, that you wouldn’t find them even on the most neglected of city outskirts. I don’t even find it aesthetically pleasing: I see towers and transatlantic liners set down in empty space. It looks like a set for Blade Runner. The same thing at Porta Nuova: big glass boxes with no quality.

Renovation of the Galleria Sabauda, Royal Palace of Turin. Design Studio Albini Associati, 2004-14.

Nearby is the Fondazione Feltrinelli. Do you fail that too?

It has a very imposing volume, but holds a dialogue with the context. It’s an interpretation of Milanese houses with gable roofs. Herzog & de Meuron are very “showy” architects, but they do have great sensitivity.

Other successes in Milan?

The Darsena is a very positive intervention. The fact that so many people go there now means that there was a need for a public space by the waterside. The impact on the canal has been minimal, the planners have created order and cleaned things up. It’s a pity that the river connection with the trade fair in Rho that was planned at the time of the Expo wasn’t realized. I like the Fondazione Prada a lot too. I think highly of the work of integration between the reclaimed volumes and the new addition. I even like the golden tower: despite being a bit kitsch, it’s a landmark in the city, a beacon.

But it errs on the maintenance front. The cladding of gold leaf won’t last long.

The aspect of duration is a complex one. Even Piano has not paid much attention to this in some of his buildings: after a year or two they start to show their age. It suffices to think of the headquarters of Il Sole 24 Ore. The sliding external drapes used to filter the sunlight were a nice idea, but the bright green color they had when the building was opened has faded with time, the light has bleached the fabric. They ought to be changed continually. It’s partly the client’s fault: if it had had the idea of durability without excessive maintenance costs clearly in mind, it would have asked the designer to use his wits.

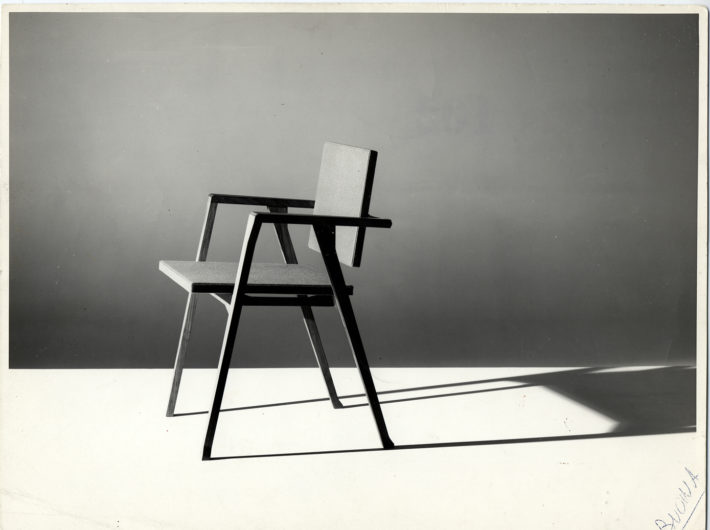

Franco Albini, PT1 Luisa chair, made by Poggi, 1950-55, Cassina reedition, I Maestri collection, 2008. Albini arrived at the definitive design after fifteen years of continual reworkings and five versions had been brought into production (1939, 1942, 1949, 1950, 1955). Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

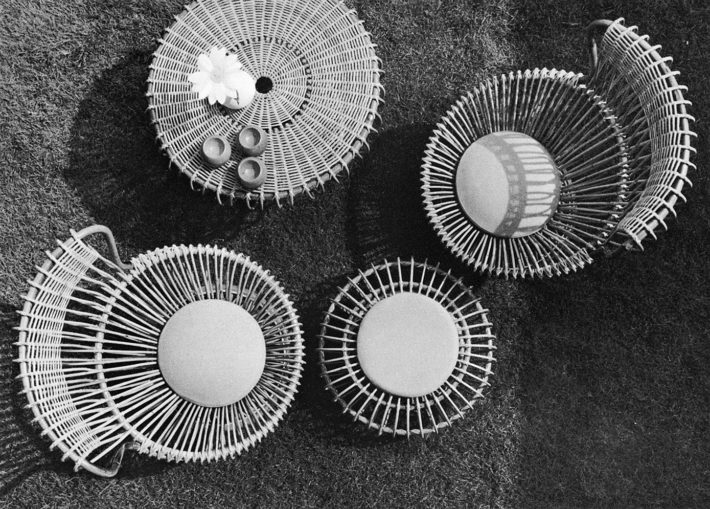

Franco Albini and Gino Colombini, Margherita armchair, made by Vittorio Bonacina, 1955. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

Franco Albini, different versions and finishes of the PT1 Luisa chair, made by Poggi, 1950-55, Cassina reedition, I Maestri collection, 2008. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

Franco Albini on a climb, 1950s. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

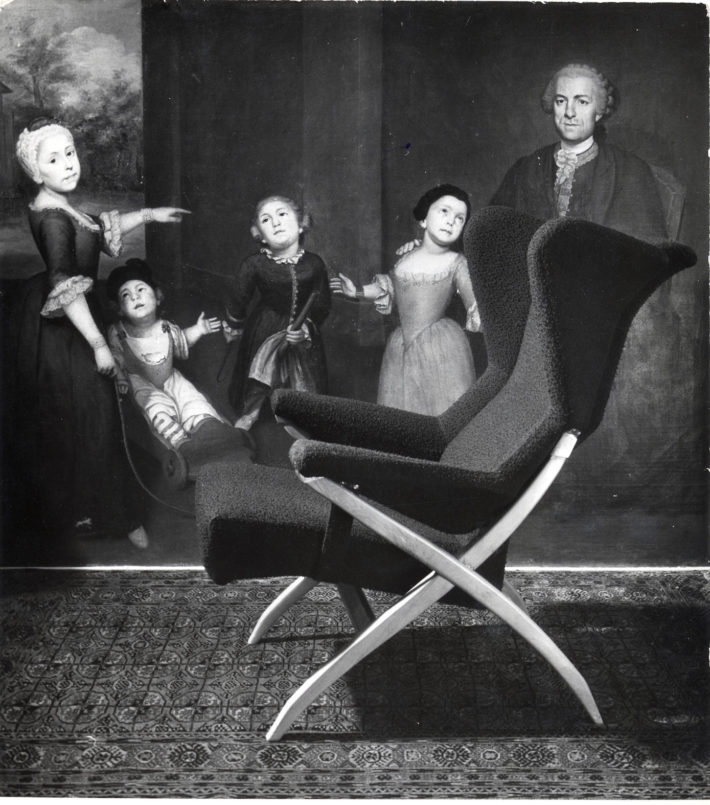

Franco Albini, Fiorenza armchair, designed in 1940 for the 7th Milan Triennale, made by Arflex in 1952 and Poggi in 1967. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

Franco Albini and Franca Helg, PL19 Tre Pezzi armchair, made by Carlo Poggi, 1959. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

Franco Albini and Franca Helg, Olivetti Pavilion, Expo Italia ’61, International Labor Exhibition, Turin 1961. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.

Franca Helg and Franco Albini with their studio assistants, Milan, 1961. Courtesy: Fondazione Franco Albini.