21 February 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Bjarke Ingels’s turn.

Klat #04, fall 2010.

Bjarke Ingels Group, or BIG, is the eponymous brainchild of the Copenhagen-based architect who recently completed the Danish Pavilion for the Shanghai World Expo and continues to win commissions in Asia, Europe and now in the Americas. After nearly ten years of independent practice (first as cofounder of PLOT and then of BIG) following his time at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, the irrepressible young architect sits down to talk with Jeffrey Inaba about the surreal, Vernacular 2.0, conspiracy theories and architectural evolution.

Let’s start by talking about the creative process at BIG. You’ve mentioned that a good idea and a good joke are similar because in each case the listener immediately gets it. Can you elaborate?

I think a good joke shows you the possibility of a parallel world. In telling a joke, the teller builds up a context by describing facts and conditions that are recognizable and reasonable, and then when the punch line arrives, it chimes completely with everything that you’ve accepted as the reality of the premise, but the response is unexpected and therefore funny or surreal. In that sense, the joke is the possibility of an alternative reality nested in reality, and discussing architecture is the same thing: there is a buildup, the formulation of an argument, an analysis that establishes conditions that are pragmatic, even boring or at least completely recognizable, but then once the punch line is delivered in the form of a proposal, it might be unexpected but it plugs smoothly into the buildup that you have just accepted as the context. The genesis of something funny and something brilliant or innovative or paradigm changing are very similar. Quite often the brainstorming process in our office starts with a dry analysis and then once we look at the facts we search for things that are surreal or funny, because if there is something surprising to you, it might also be surprising to the world, and maybe the world hasn’t yet made room for this surprising fact. Looking for the weird stuff is looking for the question that will trigger a more interesting answer.

BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group, TED Building, Taiwan. Rendering BIG

As you suggest, the architect essentially performs two roles: analyzing and defining a problem, and then proposing a solution. This very basic procedure differs greatly from one office to the next. It could be done in a mundane way that leads to a predictable answer, or it could be carried out in such a manner that both the question and the answer exceed one’s expectations. Can you talk about how this process works at BIG?

When we design a project we look for irregularities. What stops an architect, if he or she is doing a school, from finding the last really nice school and just repeating it? Why do we start over every time? I think the reason for doing a new design and not just replicating an established typology is that there is always a condition, either in the context or in the economy, that has changed. Say, in the case of the school, it might be a change in pedagogical philosophies. Once that is discovered there is a reason for doing things differently. And one way to approach this new context is to try to introduce something you would not have found in that situation before. A lot of humor is based on the unexpected presence of random objects in an unlikely place. I think the 19th-century French writer Comte de Lautréamont said: “Beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.”

For every architect, there is the challenge of striving to be as experimental as possible while also being able to successfully communicate the rewards of the experiment to others. One of the reasons BIG’s proposals effectively communicate their ideas is the familiarity of the forms. Can you discuss how this comes about as a result of the design process? I find it interesting that there is an unexpected relationship even though the architectural forms or references might be familiar.

An architectural brief almost always assumes an imaginary traditional solution. So an architect has to somehow take into account that there is an implied solution and no matter what proposal the architect makes, the scheme is going to be competing against it. For instance, we are doing a project on the West Side of Manhattan that covers an entire city block. We started by looking at the classic response to the urban block, which in the case of Manhattan is the loft typology that uses the block’s entire depth, or the skyscraper where part of or even the whole block is extruded upward to the maximum extent. We tried to ask ourselves if it was possible to introduce another typology: in this case, the perimeter block – the classic European typology of a wall containing the functions required by the program that embraces an oasis at its center. We did three projects in Copenhagen that tried to escape the perimeter block in one form or another, and it’s almost uncanny that once we get a chance to deal with a different urban condition, we are drawn back to it. Because of the unusual encounter of the perimeter block in the Manhattan context with the asymmetry of the site (one side faces the Hudson River), we transformed the generic orthogonal massing into a tilted one that takes advantage of the views of the water and the abundance of light. So first an unusual generic typology is introduced, and then specific manipulations are applied to it. With most of the things we do, we start with one of the classics and we try to criticize it in order to find a reason to do something else.

For architects there are always other architects who lie in the back of their mind and serve as sources of inspiration. Would you tell Klat readers which architects loom large in the BIG world?

At the beginning of our monograph, Yes is More, we pay tribute to some of our heroes by introducing them in the genealogy of the phrase “Yes is More.” They include Mies van der Rohe, Philip Johnson, Robert Venturi and obviously Rem Koolhaas. Obama even manages to work his way in there! I would definitely have included Le Corbusier if he had said anything remotely related to “Yes is More.” As with the idea of evolution rather than revolution, I don’t believe in starting from scratch. I believe the world is a long evolutionary laboratory where typologies have evolved because they have certain attributes that make them successful. So you can look at the city today as a sort of fossil memory of all the typologies that worked. And all the buildings that eventually get knocked down or that never get built, metaphorically fill the graveyard of all the species that died before they could pass their attributes on to the next generation. The ideas that our ancestors have developed are a pretty good point to start from before you begin to stack bricks on top of one another.

Before you were talking about the surreal aspect of your projects. A central feature of the surrealist mode is the Paranoiac-Critical Method which assumes that paranoia could be a creative force because the paranoiac sees things in the world that others don’t. Is this something you’re referring to when you say a project has a surreal quality?

A successful work of art, like a well-designed work of architecture, is something that expands people’s perception of the world, that highlights aspects of society which aren’t usually noticed, but which cannot be ignored once they have been revealed. It widens a person’s perception, like a painting that might capture light in different ways, or music that introduces the beauty of certain sounds that would normally be heard as noise. In architecture this means bringing out aspects of human life, and by accommodating them, a person becomes aware of them because they are physically present in a building. So in that sense this idea of the paranoid – of noticing aspects of the world that other people don’t see – is a very powerful tool for the architect. I’m currently working on an idea of the paranoid that starts with the question: “What if Gaudí hadn’t died when he was working on his Manhattan skyscraper?” It was a completely different kind of skyscraper that might have spawned a different Manhattan high-rise. But it never happened, because Gaudí was killed by a streetcar and didn’t live to complete the project.

BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group, Expo 2010, Danish Pavilion, Shanghai, 2010. Photo: Iwan Baan

Do you think perhaps it was murder by urbanism? Did the immaterial and material conditions of the city join forces to kill him?

You often hear architects, myself included, whine about all the factors that killed a certain project. I think the world has become immune to whining architects. I’m trying to suggest in this novel I’m writing that maybe it wasn’t only the economic or political conditions, the production apparatus or the unions that killed Gaudí’s project, but that maybe there was an actual conspiracy to kill him. There is this incredible coincidence that the history of architecture is studded with architects who died under weird circumstances. To name a few, Carlo Scarpa fell down a staircase and broke his neck; Louis Kahn was found dead in the men’s room at Grand Central Station; Eero Saarinen died at the age of fifty-one from a botched operation. And long before Frank Lloyd Wright had his major breakthroughs – projects like Fallingwater, the Guggenheim and the Johnson Wax Headquarters – his entire family was butchered in an arson attack at Taliesin. Maybe he was supposed to be there and not his family? Maybe the attack was a preemptive strike and he was away only by chance? There is this American architect who apparently died falling out of a window while sleepwalking… That sounds like a really lazy cover-up. Of course, it’s a highly paranoid theory, but the main idea is that it’s going to be a way for a bigger audience to appreciate the forces that actively inhibit the free unfolding of architecture. Our world could be much more accommodating, much more ecological and enjoyable than it is. Our cities could be more fit for human life. We could have an even higher quality of life than we do now. The reason we don’t is that there is a series of interests that are maybe unconcerned with the common good, or maybe have no investment in creating the best world possible. By claiming that these interests have formed an alliance and are systematically killing off the freedom fighters of architecture, it might be possible to get a bigger audience interested in understanding the challenges faced by architects. Now I’m not claiming that any of these architects were really killed. I’m just trying to make a viable case and therefore maybe get a slightly more attentive ear, because if there is something that can really draw people’s attention it is a good old-fashioned conspiracy theory. Whining architects are not exactly a bestseller…

Just like almost every other architect on the planet, your work addresses environmental concerns. With many of your projects you go into quite a bit of detail to explain their ecological responses. But I get the sense that your interest in exploring environmental parameters is not just for the sake of making buildings sustainable for a better, greener world. There definitely is that dimension of responsibility in the designs, but is that the only imperative? Are there other reasons for engaging these issues?

I think that talking about architecture in nebulous, artistic or esoteric terms makes it vulnerable when you’re talking to an investor, developer, user or whomever it might be that has a very specific need they want the architecture to meet. If architecture can create an alliance with something more hardcore, like science, or play an active role in saving the future of our planet, it would give the architect a more powerful position as an active problem solver. So I have been curious to find ways through which architecture could gain an ally by siding with sustainability. On condition that architecture benefits from it aesthetically. For the MoMA exhibition Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture (1964), Bernard Rudofsky coined the term “vernacular architecture.” He was trying to criticize the universal aesthetic of the International Style, responding to the fact that urban development and housing projects all over the world had begun to look the same, and that they were becoming equally predictable and boring. He showed that people from all across the planet over centuries had found ways of using locally available materials and techniques to respond to the local climate in ways that almost automatically or naturally optimized the living conditions of cities. They had completely different vocabularies and architectural styles that had evolved neither as an aesthetic nor an academic concern, but empirically over time. The exhibition was one long series of examples, such as buildings in Yemen with ventilation chimneys or Spanish underground villages where the thermal mass of the soil insulates the dwelling and creates a comfortable temperature. We are interested in exploring a Vernacular 2.0, not out of some kind of nostalgic desire for a return to an original form of dwelling, but to figure out how to calculate and model the effects of the environment on our structures and to do what we call “engineering without engines,” where we engineer the dependence on machinery out of the building. In the name of the International Style identical buildings could be constructed in Morocco and Paris, in Copenhagen and Southern Norway, but only because the mechanical systems permitted it, compensating for the limitations of an apparently universal idea of design. These mechanical systems consumed a lot of energy just to adapt the buildings to the environment. The fundamental challenge today lies in rediscovering the potentialities of the vernacular lexicon, employing all our technical skills in the construction of buildings that by virtue of their form – inclination, orientation, size and location of the windows, extent of overhangs or whatever – respond to the local climate. That way a building wouldn’t need a LEED certificate to be recognized as sustainable and it wouldn’t be necessary to remind people that it has low energy use in order for it to be interesting. It would simply appear different because it is performing differently, producing new and unexpected aesthetics. It would be an evolution from modernism through the incorporation of a vernacular logic: an extension of modernity’s faith in building systems.

PLOT (Bjarke Ingels+Julien De Smedt), Maritime Youth House, Copenhagen, 2002/2004. Photo: Paolo Rosselli

So you’re saying that to construct a building that conforms to the modernist aesthetic anywhere in the world its mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems (MEP) had to work overtime to respond suitably to the local climate, however hot or cold it might have been. MEP were the universalizing agents of modern architecture. The Vernacular 2.0 you’re talking about, on the other hand, reduces the amount of MEP machinery that’s necessary and is the basis for an engineering aesthetic in harmony with the environment, where it is not the style that is imposed on a certain ecosystem, but the ecosystem that determines a certain style. A sort of gene theory for contemporary architecture.

Exactly. We don’t have the time to let the vernacular evolve over centuries. We have to make it evolve quicker, and happily we have the tools to do so. With software applications like Grasshopper, you script the parametric engine that will allow you to discover very quickly the optimum typology, overhang, orientation of a building or whatever. As a result, we have a new vernacular vocabulary that reflects the different climate zones. When you look at the world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, and not at a map that outlines countries, you see that the climate that corresponds to a given color, like red, appears in multiple areas across the planet, symmetrically in the Northern and Southern hemispheres. So suddenly you see that a typology which has been developed in Latin America might be efficient in Northern Asia. The aim is not to duplicate the same method everywhere, but to use the same typology in specific regions across vast distances and cultures and nationalities that have similar weather.

One last question as a way to discuss BIG’s future. At a certain point an architect reckons with his or her mortality and the anxiety of having a limited amount of remaining time to do more architecture. This cliché of a mid-life crisis, which now emerges often as a mid-youth crisis, is apt I think because it represents a moment of potential mutation or hybridization in a person’s life. Now that you have been in business for nearly ten years (first with PLOT and then with BIG), how do you appraise what you have done so far, and what are your plans for the future?

You could say the first five years were spent trying to bring a little bit of the world to Copenhagen by introducing ideas to the Danish context, that had been in hibernation for a while. The next five years have been about introducing ideas from Copenhagen into an international context by continuing the experiments we have been conducting here in other countries and cultures. We are about to open an office in New York. We are coming to America because we now have some significant possibilities in Manhattan and in the States. Over the last five years I have also had a pretty consistent involvement with American academia, having taught at Rice, Harvard and Columbia. I always felt most at home in American academia because of the collaborative relationship between universities and businesses. I see a much greater potential in America to breed a fertile hybrid between public and private initiative, theory and praxis, idealism and pragmatism, than in a social democratic Scandinavian context, where public versus private is seen as good against evil. The country that invented Surf and Turf seems to be the ultimate place to explore intellectual BIGamy… A very significant part of the way we work is to move concepts, to transfer ideas from one situation to another: migration is an integral part of evolution. I’m trying to find what is the Darwinian equivalent of moving from Copenhagen to New York. When we called our company BIG it was kind of cute in a Danish context. I’m wondering how charming it is in an American context. For the last ten years we have had a home market of five million people and we have been operating in a place where it’s possible for a young kid to get a private meeting with the mayor. It offers great potentialities as well as obvious limitations. You can also say designing in a socially and environmentally responsible manner in a Danish context is a bit like trying to make Jennifer Connelly look beautiful: no effort at all. Whereas doing it in an American context seems much more of a Herculean task. However, we’ve matured enough to take on this larger challenge and responsibility. We are prepared for the next step: after all it can’t be a coincidence that they call it the BIG Apple…

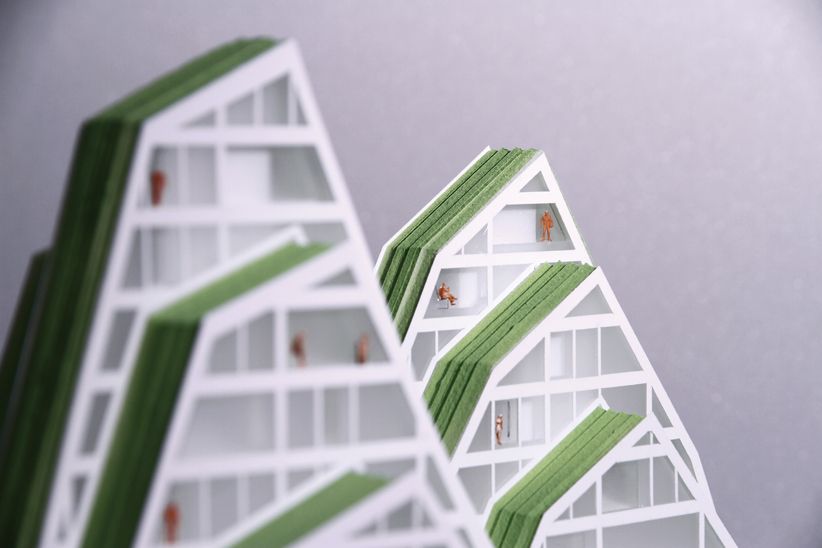

BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group, Hualien Residence, Taiwan. Model BIG

BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group, Mountain Dwellings, Ørestad, 2005/2008. Photo: Jens Lindhe