11 April 2013

Giulio Cappellini is a true polymath: architect, designer, art director, talent scout, master of style. In three decades he took the company of his Brianza parents to its current international dimension. Included by Time in its list of the ten most influential trendsetters in the field of design and fashion, he is one of the undisputed standard-bearers of Made in Italy in the world. Capable of reconciling perfectly product and lifestyle, quality and innovation, he has made history with his company, sending numerous contemporary talents into orbit. In confirmation of this, many of the company’s products can be found in the collections of the MoMA in New York, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. For some years now, he admits to us, he has preferred to devote himself to projects of global communication like the Temporary Museum for New Design, the fair-cum-museum he organizes every year together with Gisella Borioli of Superstudio, hub of the Fuorisalone in the Tortona district, now being held for the fifth time. So let’s give him the floor.

Giulio Cappellini

2013: the crisis in the Eurozone, the worldwide economic situation, the emerging countries coming to the fore. All this makes me want to ask you: is Milan still so central for design?

Milan continues to be a point of reference for the world. Numerically, attendance is very high. There is no other trade fair in the world that is able to attract 300 000 high-profile visitors: I’m talking about insiders like designers, architects, opinion leaders, buyers and the press. On the one hand, the city has to respond to this influx with all the services required. On the other, the event has to maintain very high levels of quality. Today there are design weeks of the highest quality in other parts of the world, even if on a smaller scale. We must not rest on our laurels, but have to go on improving.

A year ago I put the same question to Gisella Borioli: Fabio Novembre has declared that the first world capital that finds a way to form an alliance between public and private will take the Salone away from us. Do you agree?

A month ago someone wrote in the New York Times that nowadays the new home of creativity is London. Without wishing to take anything away from 100% Design, I can’t agree with this statement. Working in the sector, it has become clear to me that facts count a lot more than words. For me the principal aspect of Milan, the quality of the presentations, still puts it on top. And then, undoubtedly, the success of our design week is also liked to all the fringe events that come together in the so-called Fuorisalone. Here no one beats us.

Where, in your view, is the weak link, if there is one?

Milan’s real problem today is the cost of the hotels. It’s something which we’ve been grappling with for years. It’s not possible that in Milan, during Design Week, the price of rooms triples. Elsewhere in the world, they go up by 30% at the most. The consequence is that tourism declines, especially in this period of crisis. Where before foreigners would come in groups of six, now they come in threes. Where before they stayed a week, now they stay for three days.

What do you think of the boom in operations of territorial marketing in Milan (and elsewhere) carried out on the model of Zona Tortona?

I find it really impressive. Above all here, in Milan, where we are linked to the city center. We must not be dispersive, but try to make the fairs more compact and easier to get to. It would be a good idea to produce an interconnected map. We Italians are very good at what we do individually, but unfortunately we have trouble building networks.

Bong. Design by Giulio Cappellini, 2004.

Up to now we have spoken of the “city system,” of the concept of the district, which has been imitated in many parts of the world. But are we really sure of still being “number one” as far as quality and product innovation are concerned?

Italy has always been a fundamental point of reference in the evolution of contemporary design. Both for designers and for entrepreneurs, who have always been ready to take risks by working on innovation. I have to say, however, that in the last few years many companies have worked more on the concept of lifestyle and less on innovation proper. In this regard, I think we ought to be going back to the roots of design—I’m talking of the design of the fifties and sixties—making products that are useful but also extraordinary beautiful. The “Italian style” should become exceptional again.

It should be said that in the circles of contemporary art and design there is a widespread perception that the most important things have already been created. What do you think?

I don’t agree. There is still a great deal to do. Of course, it is hard to invent new and beautiful forms. Those, in fact, had already been created in the fifties and sixties—I’m speaking of design here. But we can do a lot of work on new materials, new technologies and new systems of production that, in some cases, make it possible to realize more affordable products. I think there is also still a great deal to be done on products of the right scale, the kind that can really fit into people’s homes. Today the buyers of designer furniture who live in the center of Mumbai, Milan or New York live in small apartments.

Passepartout. Design by Giulio Cappellini and Rodolfo Dordoni, 1986.

In an interview given in the past, Flavio Lucchini (artist and former art director of Vogue Italia, author’s note) claimed that “today design has become fashion.” Do you agree?

Certainly, the fact that design is no longer just a niche market is a positive sign. Today it is not just a subject for the specialist magazines, but has become a phenomenon of culture and consumption, something that interests everyone.

This year, the Temporary Museum for New Design has taken “roots” as its theme. Can you explain this choice to us?

I think that at this moment in history people need certainties. In particular, we Italians need to reflect on our history, culture and tradition. And thus our roots. Today it is wise for a company to invest in explaining everything that lies behind its products. Because communicating its own history, the planning and the culture of the company, is an act of great awareness, and one that generates confidence in the end consumer. Design should not be seen solely in terms of an object that has sprung from the trend of the moment, but as something that is part of our daily lives, and that can be handed on. It is partly for this reason that we favor an approach that is “less fair and more museum.” This is what Gisella and I have set our sights on this year.

Temporary Museum for New Design

One of the novelties of this Design Week is the newly created Sarpi Bridge (the district of Via Paolo Sarpi and environs, which coordinates companies and designers coming from China, Japan and Korea). How do you view the new powers of the East?

China can no longer be considered a nation of copycats. From the commercial viewpoint, despite the presence of the well-off young generations, it still represents a relatively small market for Italian design. The same cannot be said of fashion, where the numbers are very different.

How do you explain this difference?

Fashion is something that you show off, the home is not. For the affluent young Chinese, wearing Prada, Zegna or Armani is a mark of distinction at the moment. In interior decoration, the mark of distinction up until now has been traditional classic furniture. Designer furniture is something that has yet to be discovered in China, but the time is coming. Communicating the strength of the brand will be vital. For example, among fashion companies those who entered the market without telling the story of their product have had only relative success. While those who, like Zegna, succeeded in giving their brand a strong identity have seen an extraordinary market open up.

Talk to me about Cappellini Love, a wonderful project of yours.

The ambition to work with designers from all over the world has always been in the Cappellini company’s DNA. We like to deal with different cultures, histories and traditions. In every country there is a craft culture that is normally only used for the manufacture of local products. We have had the idea of transferring it into objects of contemporary design. We started in Africa with the Nelson Mandela Foundation, last year we worked with Vietnam and this year we are presenting a Peruvian project, in collaboration with the Fondazione Don Bosco. It is an important, social project that means a lot to us, because we are able to work with countries that have a weak economy on giving a new input to local jobs. If you think about it, it is an approach that would be valid in Italy too: we have extraordinarily skilled artisans who are “dying out” because they no longer have a market. Today when we speak of design we speak of industries, but none of them could have existed without good craftsmen behind them.

You are famous for being a great talent scout. The “craftsmen” in question are Tom Dixon, Jasper Morrison and Marcel Wanders: all big foreign names. I’ll say something provocative: wouldn’t it be better, for the purposes of protecting “Made in Italy” and using it to advantage, to have more regard for our fellow Italians?

Cappellini has certainly launched the careers of some international stars of design, which are the ones you’ve mentioned, but let’s not forget that Piero Lissoni, Carlo Colombo and Ilaria Marelli also started out with us and this year there are some new young designers making their debut, like Matteo Zorzenoni and Massimiliano Adami. They don’t do as many projects as Morrison, but on my part, let’s be clear about this, there is no closure. It doesn’t interest me whether a designer is 20 or 80, whether he was born in Milan or Sydney. For me what matters is that he’s good. And then I’d like to stress the multicultural bent of the company. As I was saying earlier, we like to work with different brains, coming from different nations.

I’ll end by asking you a question that everyone does, but it’s an important one. What advice do you have for someone who’s just graduated and wants to work as a designer?

I’d advise him to do few things and do them well, trying to sound out the market and to always work on innovation. I know that a young man or woman who has a good idea would like to see it realized and put into production at once, but you need to work hard and do things by degrees. It’s not enough just to come up with a beautiful rendering. Young people are often hooked by the more superficial aspect, especially during Design Week, when they see famous designers pursued by the press, a bit like rock stars. All the big names you mentioned before are people who started to work as students, or as soon as they graduated, and who have devoted 15-18 hours a day of their lives to their projects. And they’re still doing it today. It’s not enough to design a chair to become Philippe Stark. It takes ability, passion and great professionalism. And the world still has room for many good ideas.

Giulio Cappellini

Passepartout. Design by Giulio Cappellini and Rodolfo Dordoni, 1986.

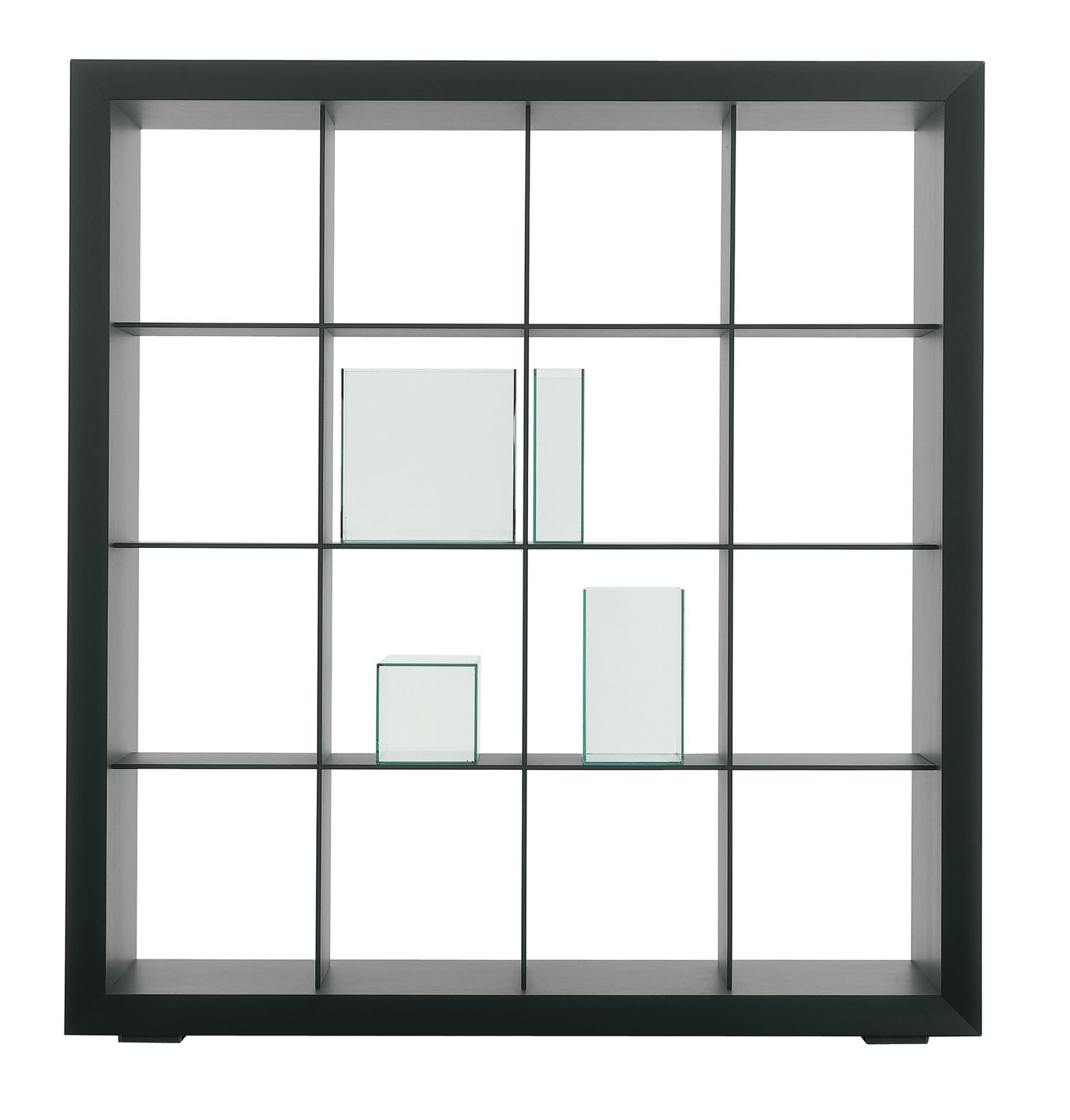

Luxor (open). Design by Giulio Cappellini, 2008-2012.

Temporary Museum for New Design

Org. Design by Fabio Novembre for Cappellini, 2001.