15 April 2014

Thirteen is the number of seconds that passed between the explosion of the first bomb near the finish line of the Boston Marathon and of a second bomb, a few hundred meters farther back, at 14:39 on April 15, 2013. Three is the number of people killed, including an eight-year-old boy; 264 the number of people injured, many of them losing limbs. Nine is the number of days it took to reopen to the public the street where the bombs went off, which is no ordinary street. “New York City has Fifth Avenue. Paris has the Avenue des Champs-Elysees. Boston—the newer, modern Boston, anyway—has Boylston Street,” wrote the Boston Globe in order to explain to the world the significance of the place in which two Chechen brothers, Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev, had put two backpacks, each containing a pressure cooker filled with gunpowder extracted from fireworks, bolts, nails, bits of metal and ball bearings. Boylston Street is “a vibrant nexus of commerce and culture threading its way through the heart of the Back Bay,” the most important, affluent and representative district of Boston: in a certain sense, in short, Boylston Street is Boston.

Boylston Street runs for 3.5 kilometers from Park Drive to Washington Street, in the vicinity of Downtown Boston. Above all in the two central kilometers that separate Massachusetts Avenue from Tremont Street, Boylston Street has everything: residential zones and skyscrapers, churches and restaurants, tourist attractions and ugly highrises. The Boston Globe puts it best: “Boylston Street is a stew of urban grit and upscale luxe, where one can buy a lottery ticket or a latte, catch a softball game on Boston Common or a musical at the Colonial Theater, take a course at Emerson College or the Berklee College of Music, or stroll all the way from Chinatown to the Fenway. It’s where the old […] and new […] sit cheek by jowl, inspiring millions of visitors annually to marvel at the city’s past, present, and future.” This sounds a bit like something a tourist board would come up with, as is often true of somewhat banal expressions, but at times expressions are banal because they’re true. Boylston Street really is like that: certainly much less glamorous than Fifth Avenue or the Champs-Elysées, but nevertheless a place where dozens of different languages are spoken, where very old family-run stores coexist with Hermès and Gucci outlets, rather sleazy pizzerias with high-end restaurants, a majestic library and many important cultural and educational institutions—we are after all in the city that boasts perhaps the two best universities in the world, Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Boylston Street is named after Ward Nicholas Boylston, a wealthy merchant and philanthropist of Boston who at the beginning of the 19th century donated stacks of money to Harvard University on the sole condition that it awarded a professorship to John Quincy Adams, who would be elected president of the United States a few years later. It has not always been the city’s main street: this happened around the middle of the 20th century, after the extension of the subway and the construction of two tall skyscrapers: the John Hancock Tower and the Prudential Tower. But the best way of describing it is not to proceed in chronological order, as if it were a history, but to move from door to door, as if on a stroll: as if we were walking along Boylston Street from the west, from the point where it crosses the Muddy River.

Boston Public Garden.

Before it reaches the river, in fact, Boylston Street is for long stretches an ordinary main road of an ordinary big city, with gas stations and ugly stores, nondescript buildings, every so often a cafeteria, a laundromat or a subway station. After a few hundred meters, though, as it starts to run alongside Fenway Victory Gardens, the street changes: on one side you begin to see low apartment blocks; on the other trees, the Muddy. After the intersection with Charlesgate a piece of the more famous Boylston Street starts to come into view, commencing with the Prudential Tower in the distance, and the zone becomes more elegant and residential. We have still not reached the real center. The flowerbeds are neat. The façades of the buildings are pale and clean. The cars move in a single lane: it is no longer a wide road.

There is an imposing building on the right, with an entrance framed by four columns: it is the seat of the Massachusetts Historical Society, designed at the end of the 19th century by Edmund March Wheelwright, city architect of Boston at the time. It is an institution that today organizes various events on the history of the United States and the building is officially classified as a National Historic Landmark, i.e. a place considered to be of great historical interest by the government of the United States. At the time of its inauguration, the Boston Herald wrote that the building would become known as one of “the surest storage batteries of historic knowledge in the city.” In other cities a place of this kind would be sufficient in itself to fill a street, but here we are just at the beginning; and walking just a few meters farther, still on the right, we come to the Berklee College of Music, an extraordinary place where so many noteworthy people have studied that Wikipedia has devoted a special, interminable page to its alumni: Steve Vai, to mention just one, but my eighteen-year-old self would have immediately noted four members and former members of Dream Theater, among many others. The Berklee is regarded as one of the most important and prestigious places in the world at which to study music and has so far turned out the winners of 229 Grammy Awards.

In all this, however, we are still only approaching Back Bay: we have reached the entrance to the most famous part of Boylston Street. We go past Little Steve’s Pizza, a pizzeria open till late that for this reason has become a meeting place for fans coming out of Fenway Park after Red Sox games, and run into an enormous building, the John B. Hynes Convention Center. It was built in 1988 and lots of things go on there, including an annual grand fair for lovers of Japanese cartoon films, a big New Year’s Eve party and the simulation of the United Nations organized by Harvard University. Opposite stands the Tennis and Racquet Club, another place that has existed for over a hundred years and that houses the city’s oldest sports club, where any sport that entails the use of a racquet, from tennis to squash, is practiced and promoted.

Massachusetts Historical Society.

From here onward, the kind of people that you meet on Boylston Street also changes. The street becomes more diverse and variegated: you start to notice students, along with a few tourists; locals begin to mingle with people who come there to work. You run into fewer people with shopping bags and more clutching a takeaway cup of coffee. As a consequence the number of languages that you hear being spoken also increases, as does the frequency with which you pass by a restaurant or a Starbucks. It’s the sort of thing which you become aware of only after a few minutes in the new context, but almost before you’ve had time to formulate this thought you find yourself in front of the gigantic Prudential Tower, the second tallest building in Boston (the tallest if you count its radio mast): 52 stories and on top a terrace—the Skywalk Observatory—that is the highest observation deck in New England and offers a marvelous view. When it was built, in 1964, it was the tallest building in the world outside New York; today it is not even among the top fifty in the United States. The at once sad and funny thing is that the Prudential Tower has always been considered very ugly, megalomaniac and out of place. Under normal circumstances an ugly building will be given the prize for the ugliest building in the city; the Prudential Tower has actually lent its name to the prize for the ugliest building in the city, the Pru Award. But the locals have grown fond of it with the passing of time. When an important game of baseball or ice hockey is played, the lights on the walls of the Prudential Tower spell out words like “GO B’s,” in reference to the Bruins, or “GO SOX” for the Red Sox. After the bombs at the Boston Marathon the lights formed only the numeral “1,” in a declaration of support for “The One” fund for the victims of the attack. An architecture critic has written that the skyscraper “has been the symbol of bad design in Boston for so long that we’d probably miss it if it disappeared.

A few meters farther on there is the Apple Store, unnaturally and yet elegantly different from everything around it, glass, concrete and a large apple with a bite taken out of it at the center. Then a big hotel for well-heeled tourists—we are now right in the most elegant part of the street—and on the left, at number 755, there is the Forum. A restaurant that is rather expensive but good, but above all the restaurant in front of which the second bomb went off on April 15, 2013. The explosion smashed the windows and wrecked part of the interior. The waiters and staff of the restaurant were among the first to aid the injured. It remained closed for a long time and was reopened only in August, first with a benefit night and then with regular service. Every day someone passing by, often a tourist, stops to take a photograph; the waiters have got used to it.

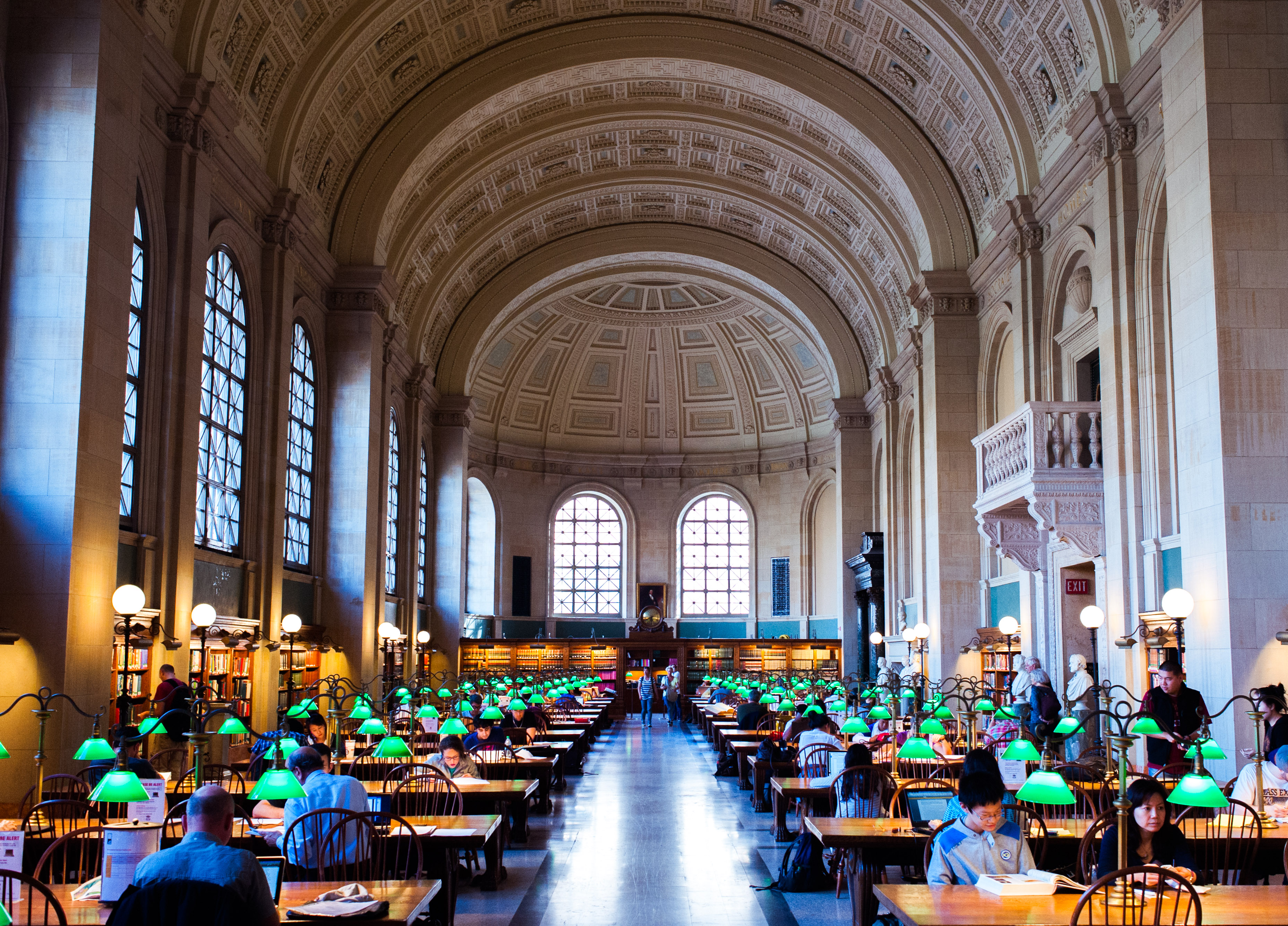

Continuing on our way, past a fairly ugly shopping mall, we find ourselves in front of the monumental Boston Public Library: a massive structure, with lots of concrete, it looks like a fortress or the headquarters of an old bank. But it is a library and on its wall is written, in very large letters: “The Commonwealth requires the education of the people as the safeguard of order and liberty.” I’ve noticed that words which in other contexts might seem absurdly bombastic and solemn sound less so when applied to culture: and I recalled being impressed by another inscription I saw carved in marble on the New York Public Library: “On the diffusion of education among the people rest the preservation and perpetuation of our free institutions.” The Boston Public Library contains more or less 9 million books and eats up one percent of the city’s entire budget every year—that’s a lot, if you think about it. But it’s an incredible place. Inside there is a courtyard inspired by that of the Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome and a collection of the highest quality, especially with regard to the history of art and the history of the United States. Opposite stands a little store selling sports goods of the kind that for a year now it has suddenly become impossible not to notice, and not just because the sign says Marathon Place: it’s the spot where the first bomb exploded on April 15, 2013. In a review of the store published on Yelp a few months later, a young woman wrote: “After the bombings I went in to the Copley store to get some fuel for a half marathon I was running and I overheard a customer thanking the staff and start crying and was really touched by the way the staff person gave them a hug and thanked them.”

Apple Store.

We have almost reached the central point of the central street, i.e. Copley Square, surrounded by a large number of significant buildings and places, in addition to the ones mentioned above, as well as the spot where the Boston Marathon used to end until 1986. In front stands a beautiful Gothic building, the Old South Church, and a little farther on there is the Trinity Church: the only church in the country—as well as the only building in Boston—to be included on the list of the “ten most significant buildings in the United States” drawn up by the American Institute of Architects. That list has been revised and updated every year since 1885: Trinity Church of Boston has always been on it. Unfortunately the fact that you have to buy a ticket to visit it puts off the majority of tourists.

At this point it would be understandable if someone were to think: more? Are there other special places on Boylston Street? How many important and noteworthy things can there be on a single street? Well there is more. There is Five Hundred Boylston, a building in postmodern style that viewers of the TV series Boston Legal will recognize at once; there is a multitude of bars and restaurants, very different from one another; above all there are the entrances to Boston Common, the oldest urban park in the United States, the largest green space on tourist maps as well as the place where Martin Luther King Jr. and Pope John Paul II made speeches over the years. There is a large, old and marvelous piano store, which has been in existence for over a hundred years and has recently fallen into disrepair, and there is Emerson College, specializing in communication and the liberal arts.

Old South Church.

We are now outside the central part of Boylston Street. The street grows more normal, emptier and even slower: you get the impression of having left the smells and noise behind. Around here there is the Boylston stop of the subway, the oldest in the United States, and the Saint Francis House, a dignified and well-organized refuge for the city’s homeless: every year it puts on an exhibition of works of art by the homeless; many of them are sold. But in short, we are outside, we have left. We have walked along the shopping streets and the ones where you go to eat something, the ones with cafés that make you want to go inside and the ones with museums and cultural institutions, the ones with churches and the ones with universities, the ones with offices and the ones with houses: we have walked along them all and they were all the same street, which manages to be at once affluent but not hectic, special and ordinary. A place where it is “enjoyable to walk as the sidewalks are wide so u can walk slow,” as someone has written laconically on Tripadvisor: something unusual for the main street of a big city. The description can also be applied to Boston as a whole, and not just today: it is also valid for the Boston of a year ago, that of the day of the bombs and the other sad days that followed. When a man interviewed by the Boston Globe not long after the attack was asked about the atmosphere in the city he replied: “You get a sense that something happened here, but, in a way, it’s almost back to normal. This is Copley Square. This is Boston.”

Tennis and Racquet Club.

Boston Public Library.

Old South Church.