26 February 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Oliviero Toscani’s turn.

Klat #03, summer 2010.

Oliviero Toscani is much more than a photographer: he’s a brand. His OT logo comprises Oliviero Toscani Studio, OT Horses, OT Società Agricola (which produces the new OT Wine) and La Sterpaia, Bottega dell’Arte della Comunicazione (Workshop for the Art of Communication, ed), in Tuscany, where, in every project, photography is the central medium in the narration of contemporary life. It doesn’t matter if this happens through advertising campaigns or itinerant shoots to map Italy through the portraits of its inhabitants. Around the Mentor, the young people who work here come from all over the world, with a yen to liberate their potential for creativity. Photos, horses, red wine, communication, books and even a line of eyeglasses he has designed himself. These are multiple aspects of a single vision, that of Oliviero Toscani: radical, inimitable, in love with reality and its image. From the famous campaigns for Benetton, that gave visibility and depth to differences (sexual, political, religious), to the latest efforts that have focused on the widespread yet hidden problem of anorexia, Toscani’s images shake things up. His shots, prepared through a long process of research and writing, are like turbulence inside the condition of indifference caused by the excess of visual information. Strong, controversial, scandalous images: who can forget the face of the AIDS patient on his deathbed, embraced by relatives, the icon of a decade in which armies of people died under the blows of the HIV virus? Toscani’s photography puts the viewer face to face with his own individual responsibilities, with no escape route, simulating him to question his here and now, just like much contemporary art. But be careful about comparing Oliviero Toscani to the art world, he might get very angry…

I’d like to start by asking you what ethics means today, because I think it is also a key word in your work at La Sterpaia.

I don’t believe ethics has changed over time: it continues to be something discomfiting, having much to do with integrity and the human condition. Ethics today often stops short at form, economics, interest. The only ethics worthy of the name is the one that has to do with the human condition and human dignity. I don’t recognize any other, more superficial or image-conscious type of ethics. I don’t mean, by saying this, that in the past ethics had another depth, I don’t belong to the ranks of those people who think the past is better, in any case, than the present. I’m only saying that ethics, true ethics, is rare and immutable.

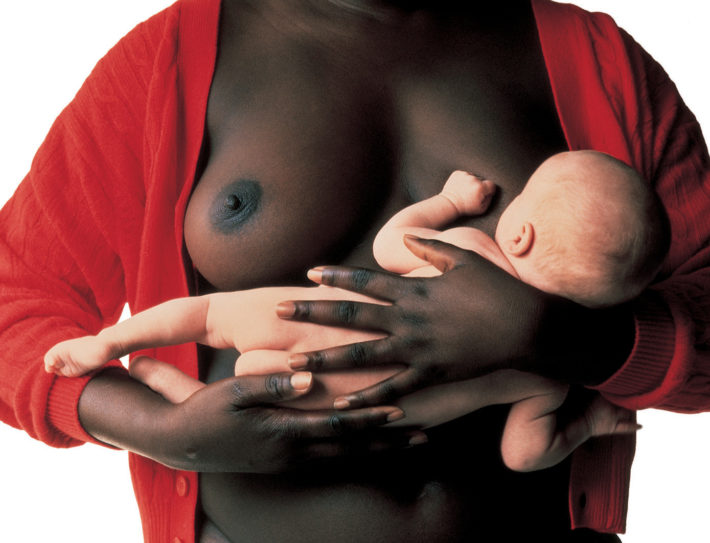

Oliviero Toscani. Advertising for United Colors of Benetton, 1989. © Oliviero Toscani.

Let’s shift our discussion more precisely to the image, and ask what makes an image ethical.

There is no such thing as an ethical image, at least where photography is concerned. For painting the matter is completely different, because with this language it was possible, for example, to paint a Virgin Mary, Hell and Heaven, the entire repertoire of the misleading publicity of the Catholic church. In the Sistine Chapel, the painting narrates characters, facts and events that never existed, just like the religious imagery and painting of the Renaissance in general, which we can undoubtedly define as falsehood. After all, communication has always served power and art is simply the highest level of communication, communication at its apex. Art has always exploited power to express itself, and power has always exploited art to assert and consolidate itself. The church made people draw or paint the Virgin Mary, but it has never been proven that she was a virgin and, above all, that she ever existed. In painting, in short, you can represent anything, even events or episodes that never happened, telling lies. With photography the situation is different, because a shot, primarily, documents reality, facts, things and people around us. Of course a photograph can also be retouched, especially today, but the starting point is different. Violence, massacres, abused children: everything that is right or wrong finds a place in historical memory through photography. So I believe there are no photographic images that are more or less correct from an ethical standpoint: all images are ethical, even a family album and the photos I find in the catalogues of shopping centers, because they are documents of what we are and what we were, of the human condition.

You are the son of a photojournalist. What did your father teach you about photography? Though in different fields of action, photography remains a shared element for discussion…

But I too am a photojournalist! I just use less traditional means. Often a news photographer works for just one newspaper and that necessarily influences the approach, as in the case of my father, who worked with Corriere della Sera. Newspapers always have to answer to their board of directors. All photographers, not just photo reporters, create images that will be the historical memory of humanity, even when they are taking pictures of underwear for a department store. Actually, it’s possible that precisely such commercial photographs, rather than great photography, can help us to better understand the society in which we live. In effect, posters and billboards on the streets of a city tell us much more about us, about our country, than the in-depth articles found in newspapers. Advertising is the language of production and consumption, and that language is the mirror of our society.

Oliviero Toscani. Advertising for United Colors of Benetton, 1991. © Oliviero Toscani.

I was interested, though, in asking you specifically about the profession of the photojournalist, because it is going through a moment of crisis: the major agencies are closing, few newspapers can afford them, or in any case they don’t want to pay for a true photo reporting…

The path is well known: first print ruled, then television, now the Internet, the web. Today anyone can take a picture and publish it, at any time. Every historical period finds the best way to communicate. Before printing came along, you entered a church and you were shocked by the marvelous paintings, the frescoes, that represented, as we were saying, the church’s advertising. The church sold its product and did it very well. This mechanism was financed, at first, by political power, and later by industrial power. Then came the newspapers, which still protect the interests of those who finance them today. It is in the name of these interests that they use images, acquired from different sources. Maybe the web is freer. In any case, beyond these interests and the channels utilized, photography continues to represent the historical memory of humanity, and very often it can irritate those who look at it. When Lady Diana died, for example, there was concern about the possible presence of a photographer at the time of her death, not about possible eyewitnesses. This is because photography is disturbing, it puts us face to face with our individual responsibility. The image of a child leaving the Warsaw ghetto with his hands raised, taken by an unknown photographer, confronts all of us with our ethical responsibility. Thus the scandal. Blood, abuse, wealth or stupidity, it doesn’t matter. We are all responsible for certain atrocities, certain sufferings, perhaps indirectly: photography reminds us and creates a sense of embarrassment, annoyance.

Do you think that this was the case with his photograph of an anorexic girl portrayed in all her naked gauntness? A picture later used for the Nolita advertising campaign.

Of course. Anorexia is a widespread thing, a problem of society, family and lifestyle, but we pretend not to see it: it’s a reality we want to keep hidden, out of sight. That picture came at the end of a long process: I had been working on anorexia for some time, we had done a documentary on this subject, after having spent lots of time visiting hospitals. I was interested in that theme because this ailment spreads, to some extent, precisely because of the fashion brands, television, fashion magazines. A teenager reads, listens, looks around, and as soon as she understands what seduction means, if her body is not perfect, at least not according to the standards imposed by the media, she feels anxiety. It is no coincidence that our campaign was ignored, censored, precisely by those magazines. The mayor of Milan, Letizia Moratti, went to great lengths to prevent that image from circulating. But this certainly is not the only case in which everyone makes believe nothing is happening. Everyone had an idea, for example, about the homosexuality of priests and nuns, their problem controlling their bodies, but no one talked about it until today, when everyone pretends to be surprised by the news about certain sexual habits of priests. So it is not just a problem of image, but one of a lack of communication, of dishonesty in human relations.

Oliviero Toscani. Advertising for Nolita, 2007. © Oliviero Toscani.

You, however, work above all with images. How do you know when you have found just the right image?

I think I am an “imaginer” and I work to construct the image best suited to the problem at hand. It is like making a film, a complex work, like that of Fellini or Antonioni. You start by writing the story, then you proceed, removing one thing, adding something else, until you have achieved the best results. Lights, of course, are at the center of this process. All too often we forget that photography is made of light, and it is precisely the proper use of lights that lets you obtain good results, or the right image, capable of effectively, unmistakably representing what you want to say. Where the content is concerned, instead, there are particularly delicate themes for human beings, problems we have not yet solved, like sex and death, in opposition with each other: my interest always ends up there.

They say that all great artists have come to grips with the theme of death. If I told you that your work reminds me of Maurizio Cattelan, what would you say?

I was one of the few people who defended Cattelan when everyone was so shocked by his dolls hanged in Piazza XXIV Maggio in Milan. In general, though, I feel no admiration for so-called contemporary art. Art no longer has any relationship with real power, but only with that of rich collectors and museums. Its points of reference are the various Pinaults; when their wives tell them to get rid of all the artistic doodads that are cluttering up the house, they decide to build a museum like the one at Punta della Dogana in Venice. I’ve got nothing against Tadao Ando, in fact I was the first to ask him to work in Europe, but I am struck by the uselessness of contemporary art and the world that surrounds it. It is no longer applied to great works of architecture, great churches. I have reached the point of hating contemporary art, in spite of the fact that I’m an art maniac: for me, it all ended with Bacon.

What irritates you about art, besides the scene that surrounds it?

Its mediocrity, its way of getting lost in form, composition, colors, surfaces. The only goal of art is the human condition. From Munch’s Scream to the paintings of Goya or the sculptures of Michelangelo, we cannot distinguish between contemporary, modern and antique art. Can we say that The Lamentation over the Dead Christ of Mantegna is not modern or contemporary? It’s more than modern, more than contemporary! If we have to define an artwork as contemporary, then it must be missing something. Only true art exists, or its opposite, its absence. True art bridges the gap that exists between us and perfection, it helps us to understand and to bridge that space, that distance. A plant, an oak tree, a leaf don’t need art, because they are already perfect.

You work on the construction of images capable of communicating with immediacy. You must have been surprised by at least one work seen in a major contemporary art exhibition, like the Venice Biennial, for example.

A truly modern artwork has no time, no date. The Venice Biennials are commercial events made by rich people for rich people, they cannot really narrate the human condition. Nothing, really no one has amazed me: not Abramović, not Jeff Koons, who should have been a window dresser. At least in Cattelan I can recognize the intent, but he ought to switch to photography! Photography, in fact, is mass communication, it’s everywhere, you just have to open a newspaper. It doesn’t necessarily have to be kept in a closed room or a museum, it is immediately available to the audience.

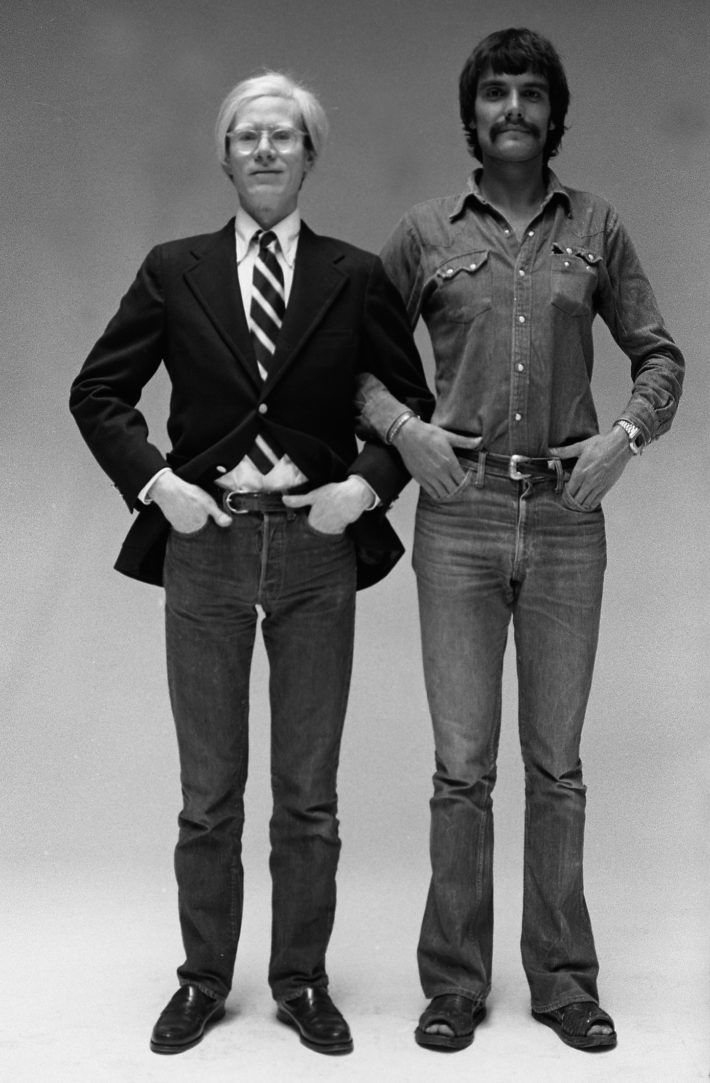

Andy Warhol and Oliviero Toscani, 1973. © Oliviero Toscani.

What do you think about the work of Andy Warhol? I know you were quite well acquainted…

Warhol immediately understood that art was a business and that everything moved around money. This awareness made him a true protagonist of art. He experienced everything firsthand. He was a Martian, the pilot of a spaceship. I appreciated his less well-known aspects: he collected antiques, he loved the Empire style in particular, all gilded things. He loved being a model, he posed for me in a Polaroid campaign: when he arrived at the studio, first he had the contract signed and then we went to lunch… It was great fun. Later he came to Italy, and we spent a lot of time together: he was truly an extraordinary personality.

Speaking of Italy, you are doing a project on this country, the Razza Umana (Human Race, ed) a group of portraits about our contemporary situation.

No, Razza Umana is here right now, but it will go elsewhere. I don’t feel any ties with Italy, I owe nothing to this country, I am actually quite fed up with being Italian. I have no respect for Italy, just think, in all these years there has never been one government I voted for! Everything irritates me, starting with the schools. When I was a student I was bored to death, and that kind of idiotic education is still with us here.

But, in the end, even a personality with your creativity can be a product of Italy.

I have been lucky and privileged, individually and as a generation: I experienced the sixties, before the movement of 1968 ruined everything. Those were years of experimentation, full of energy, during which I really tried to do what I wanted. I was lucky because I was the right age at the right time, I traveled in many countries, I lived in London in the sixties, going to art school. In short, I speak five languages and I never studied any of them, that can give you a sense of my past. The people who know what they’re doing are the ones that don’t belong to any country and, in particular, have nothing to do with our country, a nation that survives only thanks to individualities, single personalities.

Let’s get back to Razza Umana, an traveling shoot that, in any case, offers a glimpse of the present in our country.

In Razza Umana I am interested in the repetition of the image, not in virtuoso photography. I like mechanical repetition, like that of ID photos, from which you get a sense of the unrepeatable uniqueness of human beings. To explain our personality nothing is better than a photo ID: you don’t have to go to a psychoanalyst, just look at that little picture and you can know who you are. I’m interested in this almost magical content of the photograph. After all, we form an opinion of people through their portraits; this is why I think photography is the modern art par excellence.

Oliviero Toscani, Razza Umana, 2009. © La Sterpaia.

Photography is certainly the most democratic art. Everyone, no matter what the results, takes pictures with a cell phone, or with small or large digital cameras.

Everyone does it, but few do it with any awareness. People often fail to take into account all the meanings that go along with this action.

Another interesting thing about photography is its use by political figures to create a winning image for themselves…

If you’re talking about Berlusconi, he’s a one-eyed man in the midst of the blind: his taste is horrendous, Soviet. Having said that, image is communication, and communication and power help each other out.

You surround yourself with young people from all over the world. How does your creative process work?

We work together because creativity, though it is an individual path, is also the result of a shared path. Everyone has his own intuitions, and working together you understand if an intuition produces something truly creative or not. In any case, there is no democracy in creativity: the artist does what he thinks and the result becomes an artwork. I try to put together young people of this type, real individualists. We work together, but we do not become a team. Each person thinks in his own way. I think Enrico Fermi and Robert Oppenheimer had different ideas about the atom. Art and science are similar: both are looking for what is still not known, and to be creative you have to have the courage to be constantly insecure. Creativity has an element of instability, and that is why it frightens the bureaucrats.

So at La Sterpaia Oliviero Toscani is always at the center of the creative process?

Of course, though I am surrounded by creative young people, like Warhol at the Factory, I am always the one running the show. Fabrica, in Treviso, practically no longer exists, since I left: I don’t think they have done anything interesting since then.

I’d like to finish with a question about the concept of the family today: in your view, what is the family, what does it represent?

Fabrica and La Sterpaia are families. For me the family has a very important value. Personally I’m against marriage: I have six children, but I have never been married. At the same time, I am not in favor of extended families. The family, however you experience it, has to be an ethical, true, clean, highly individual choice. And, above all, it has to try to give happiness. It certainly should not be a demoniacal choice, unless someone is happy with the devil…

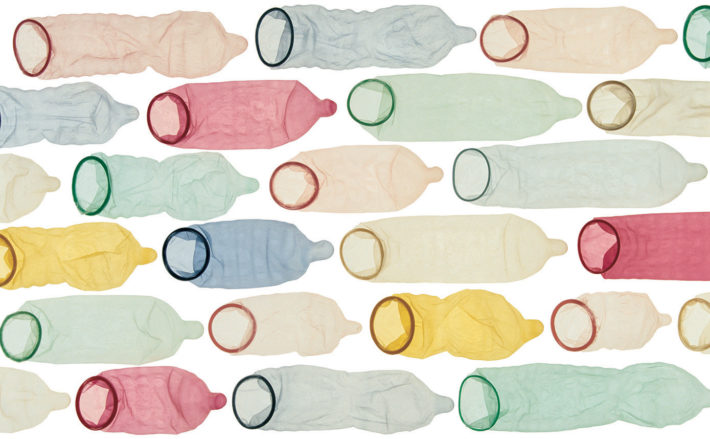

Oliviero Toscani. Advertising for United Colors of Benetton, 1994. © Oliviero Toscani.

Oliviero Toscani. Advertising for United Colors of Benetton, 1991. © Oliviero Toscani.

Oliviero Toscani. Advertising for United Colors of Benetton, 1994. © Oliviero Toscani.

Oliviero Toscani. Advertising for United Colors of Benetton, 1994. © Oliviero Toscani.

Oliviero Toscani. Advertising for United Colors of Benetton, 1991. © Oliviero Toscani.

Oliviero Toscani. Advertising for Ra-Re, 2006. © Oliviero Toscani.

Oliviero Toscani, Razza Umana, 2009. © La Sterpaia.

Oliviero Toscani, Razza Umana, 2009. © La Sterpaia.