17 September 2013

Davide Monteleone was born in Potenza in 1974. Photography entered his life in 1998, once he had given up his study of engineering. Since that time he has seen a rising tide of engagements and recognitions: first as correspondent for the Contrasto agency, then as contributor to various Italian and foreign publications and since 2011 as a member of the VII Photo agency. In 2007 he published his first book, Dusha, while in 2009 he brought out Un-Existing Line, on the Iron Curtain that, in Winston Churchill’s famous phrase, separated the East of Europe from the West. In 2012, with Red Thistle, he investigated the Tolstoyan atmospheres of the peoples of the Northern Caucasus, and following the same line of research he won the fourth Carmignac Gestion Photojournalism Award last July with a work on contemporary Chechnya entitled Spasibo. This latest project will soon be published as a book and, from November 8 to December 4, the subject of an exhibition at the Chapelle de l’Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. Davide Monteleone has won the World Press Photo award three times: in 2007, 2009 and 2011.

You set off from Potenza to explore the world. Among the various countries: the United States, the United Kingdom and a great deal of Russia, fertile ground for many projects. To what part of the world do you feel you belong?

I am and remain Italian. After all I’ve spent most of my life here and my parents are both Italian.

From January to April of this year you were in Chechnya, based in Grozny. The Spasibo [“Thank you” in Russian] project stems from your desire to photograph contemporary Chechnya. What questions prompted you to set about this work?

I asked myself how Chechnya appears, to the outside world and to the Chechens themselves. The position of the West is often banally accusatory, and so I was interested in shifting the balance toward a different perspective from the Eurocentric one and finding a new way of interpreting it. I asked myself who had really won in the war between Russians and Chechens. The Russians certainly, but it is worth remembering the fact that, thanks to their megalomaniac president Ramzan Kadyrov, the Chechens now enjoy an autonomy unimaginable in any other Russian republic.

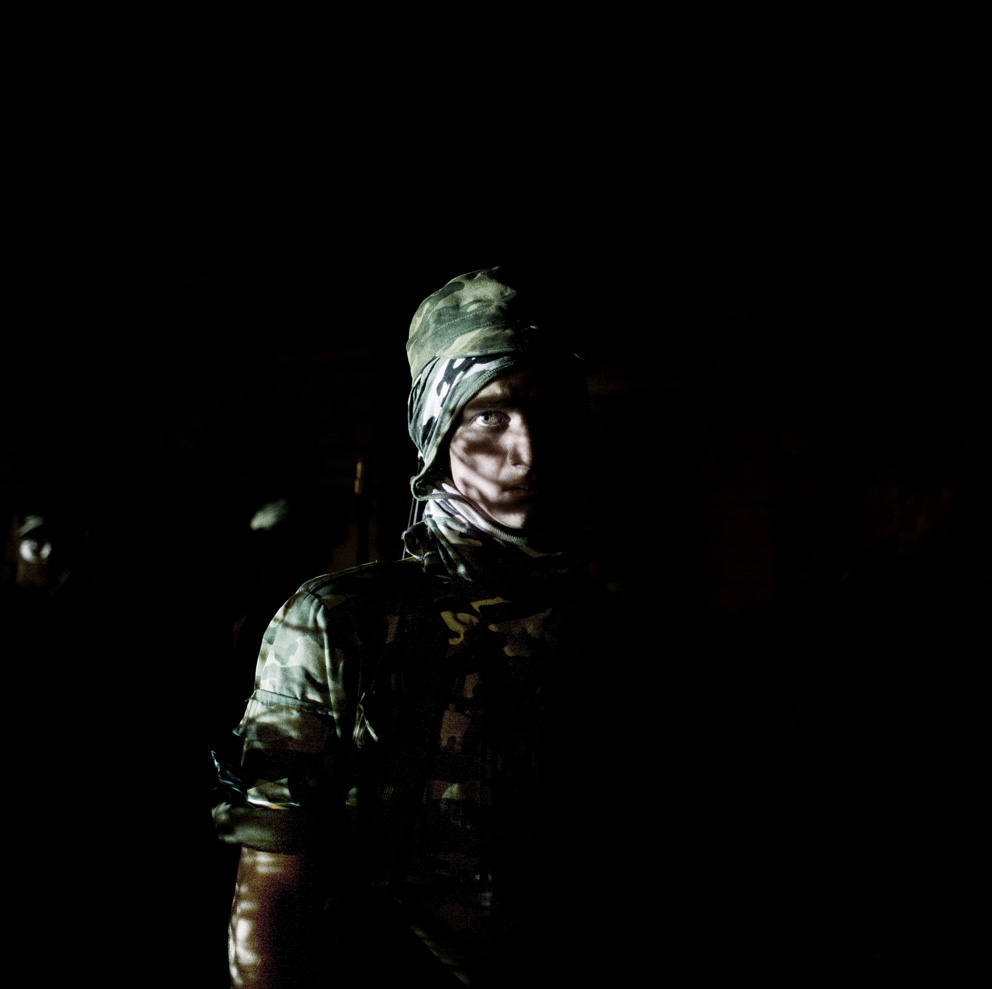

Davide Monteleone, Spasibo, Cecenia, Russia, 2013. © Davide Monteleone

All things considered a positive situation?

I’d say a very complex one. Today the effects of the psychological violence wielded by politics in Chechnya are felt everywhere: people are happy to see their houses, towns and cities rebuilt, but it is a satisfaction reminiscent of the celebrated Potemkin villages, those perfect and unreal fake constructions of the time of Catherine the Great. If you scrape just beneath the surface, you find instead that the younger generations have been subjected to a genuine brainwashing: many of them have a distorted vision of the truth and of democracy.

Female figures stand out among the photographs, like the picture of the very young Rada trying on a wedding dress. What do the women tell us about the Chechen people?

The women are tough and strong, and they outnumber the men since many husbands, sons and brothers were killed in the war. The marriage of girls at the age of 13 or 14 is a tradition in Chechnya as in other Muslim countries, and is an integral part of their culture. On top of this President Kadyrov wants to shape his country on the basis of traditions and forms that reflect his autocratic megalomania. He declares himself happy to see very young, barely adolescent, Chechen girls married to Chechen men, notwithstanding the fact that in the Russian Federation, of which Chechnya for good or ill is part, there are laws forbidding this. And yet here too the question is complex: in Chechnya women’s rights are not very advanced, but it is not possible to speak of an outright persecution of the female gender.

With the Reversed Seæ project, winner of the Follow Your Convictions grant, you documented the evolution of the Arab Spring. This summer Egypt is back in the headlines, along with the conflict in Syria. Where would you like to be at this moment, what would you like to be documenting?

I wouldn’t like to be in Egypt or Syria. Over time I have developed another way of looking at and thinking about my job. Photography focused on the news is not my style any longer, it doesn’t interest me. Unless it’s part of a wider project, with a broader perspective than the immediacy of events.

What kind of photography interests you now?

I couldn’t tell you, I’m not keen on dividing photography up into genres. Photography lives on crossovers, especially today, even from the viewpoint of the market. A photojournalist, for example, struggles to make a living and chooses to focus his research elsewhere. This means thinking creatively about your work, combining techniques and experiences, mixing studio lights and documentary photography, portraiture and reportage. Quite interesting stylistic solutions often come out of these overlaps, above and beyond genres.

Let’s talk about Russia. Gogol recalls how he met Pushkin shortly before his death and read him the first draft of Dead Souls. After a long silence, it seems that Pushkin responded: “My God, how sad our Russia is!” At a distance of almost two hundred years, could the same thing be said?

In point of fact, Russia is a little sad. It interests me because it is a society that has gone through a very rapid development, especially when compared with ours, which has long been at a standstill. The Russians, despite their gloom, are proceeding at a brisk pace. But in reality when people ask me about Russia I never know what to say: it’s like talking about a personal relationship and little secrets that should not be revealed. There are peculiarities that, even if I tried to explain them, would not be understood because they are part of the relationship between me and Russia.

Davide Monteleone, Il cardo rosso/Red Thistle, Russia, 2009. © Davide Monteleone

To stay with the great Russians, the title of your last but one book of photographs, Red Thistle, recalls the prickly and beautiful flower used by Tolstoy to sum up the hostile and proud character of the Caucasians. How important are literary influences for your work?

Photography, like all means of expression, is the product of a series of experiences and notions that come from literature, the movies, the visual arts or the most trifling daily activities, such as tending plants. Everything accumulates, and then takes shape at the moment a new idea is born. There is undoubtedly a lot of literature in my photography, but also many walks in the mountains and a lot of everyday life. We could say that a good picture is like a good book, or that a bad picture is like an awful book. Photography interests me as an aesthetic means of entering new worlds.

How did you find Moscow?

Moscow is an aggressive city, which changes very fast: at times it’s dirty, at others it’s extremely elegant. In general it has changed a great deal over the last few decades. It still has a strong Soviet feel, but now offers services and comforts on the level of New York, Paris or London. One thing that has always struck me is that in Moscow the buildings are constructed for the masses and not for the individual: this means that it’s not a city on a human scale, and complicates the handling of personal relations. From the photographic point of view, the perfect moment to take a picture is in the summer, around nine o’clock in the evening. At that time there is still a lot of light, fairly diffuse and at a low angle, which reflects magnificently off the buildings. These are moments in which the gloom of Moscow completely vanishes.

How do your projects emerge?

Reading something interesting, or listening to the radio while I drink my coffee in the morning: I hear a news item that stimulates me and prompts me to find out more. It can also happen that someone asks me to do a small job which then turns out to be much more important than I thought. An idea can arise in various ways, but to turn it into a concrete project takes a great deal of tenacity, dedication and passion. And time: the right amount of time to carry it out and get it to grow and mature, so that it can be understood and accepted by others.

In addition to taking photographs, you teach the art of photography, through lectures, meetings and workshops. Why teach photography today?

I do it because I don’t go to a psychoanalyst and I find it very therapeutic to tell other people the things that you would like to say to yourself. I joke a lot with my students. During my lessons, however, I like to make it clear that nowadays there is no real need for new photographs, and so new photographers are not needed either. With a hint of mischief and realism, I invite them to think seriously about whether it is necessary for new producers of images to be created on this planet of ours. Not so much because it’s a difficult moment or because there’s not much work, or because no one pays you or because it’s a tough job. I really believe that the image is extremely overdone. I very often ask myself whether there is any reason for my photographs to exist. And I can assure you that the answer is often no.

Davide Monteleone, Modern Odissey, Russia-Cina, 2012. © Davide Monteleone

Really?

It’s enough to think of the hundred of thousands of photographs that are posted on social networks every day. Many of them are interesting too. It’s not strictly necessary to produce more.

Let’s look beyond photography. Your first short film, Modern Odyssey, shot on board a ship transporting 70 thousand tonnes of iron, was selected for the International Hamburg Short Film Festival. Are you looking for new languages?

Who knows, in the future I might make a great movie and win at the Cannes Festival. I’m joking, but I’d like that. The video you’re talking about was born on board a cargo ship where I knew from the start that I was going to be very bored. So I decided to shoot some footage. It was a truly interesting experience.

How does Davide Monteleone work, from the technical viewpoint?

Up until a few months ago I worked exclusively with film. Now I have a hybrid system: a very traditional camera with a digital back.

Davide Monteleone, Spasibo, Cecenia, Russia, 2013. © Davide Monteleone

Davide Monteleone, Spasibo, Cecenia, Russia, 2013. © Davide Monteleone

Davide Monteleone, Red Thistle, Russia, 2008. © Davide Monteleone

Davide Monteleone. Photo: Lorenzo Poli