24 October 2014

An architect and product and fashion designer, Gentucca Bini works in a space in Milan that used to be the studio of Dario Fo and Franca Rame. Thanks to her actor and couturier grandparents, gallery-owner mother and architect father and uncles, Gentucca has always felt at her ease crossing disciplinary boundaries. Thus the hybrid condition of our time is something she has always been familiar with, long before it became the programmatic banner of a host of designers. We met her to talk about how the many facets of her work have emerged and developed. And we discovered that in her the power of intuition is combined with a strategic vision of design. Unaffectedly, she shows us that being self-deprecating and not taking yourself too seriously, especially in the field of fashion, does not at all mean being naïve. And that, on the contrary, having a plan to pursue with tenacity does not automatically imply a renunciation of humor.

Can you talk to us about the atmosphere in which you grew up?

I was raised in a very eclectic family. My father and his brothers are architects, and in the seventies they were responsible for Pierre Cardin’s overall image. My grandmother was a fashion designer, a close friend of many great artists, from Marcel Duchamp to Man Ray, from Lucio Fontana to Arnaldo Pomodoro. My grandfather was principal dancer at La Scala in the fifties and then became an actor in the theater. My father’s father was a much more level-headed man, a Neapolitan tailor who with my grandmother set up a fine atelier [the Atelier Bini Telese on Via Montenapoleone in Milan, author’s note], that was at the same time a true intellectual and cultural salon. Together, he and my grandmother designed a collection of clothes in collaboration with their artist friends: Fontana, Pomodoro, Enrico Baj, Lucio Del Pezzo, Emilio Scanavino. Well, I grew up in this environment of intellectuals accustomed to putting their ideas into practice, people who carried out their projects not so much out of professional ambition, as to give concrete expression to their designs.

And among so many fascinating professions, what did you say to those who asked you as a child what you wanted to do when you grew up?

I dreamed of acting, but there was no way. I wanted to become a ballerina too, but my grandfather realized straightaway that I was not going to have the right physique and so, rightly, discouraged me. Until one day my father told me: “Now you have to decide what to do. Take one road and then, once you have established yourself in that field, you can mix up your passions. But you have to have a point of reference.”

Gentucca Bini, Speedy, Fall/Winter 2011/2012. Photo: Michele de Andreis.

And how did you react?

I chose to study architecture because it allowed me to combine the representativeness of a gesture, attention to the image and the overall emphasis on design as the basis of all my passions: theater, set design, photography. After graduating from the Polytechnic, I took a master’s degree in industrial design in Paris, at the prestigious school of Les Ateliers, where I designed all sorts of things, from automobiles to blenders. But there too I always tried to stray from what I was doing, out of the boundaries that I was set. It was an exciting challenge and very useful to my development.

So you tackled traditional types of product, but reassessing them in your own way?

Yes, although it was not the end result that mattered, but the all-round research connected with a project, which comprised not only the product, but also its effects, the way to exhibit it, show it, communicate it.

And how did the choice of fashion come about? Was this part of a design strategy too?

Moving into the fashion system was supposed to raise my profile. Anyway, I find designing an item of clothing or a table equally interesting, for me it’s never a question of the type of product or field of application. I don’t get excited about a skirt as such, but over a design that turns out well, one that puts a good idea into practice. Fashion is the most complete framework and the one closest to the diversification of genres that I’ve always pursued, but in the end I chose it because, unlike architecture and design, every six months it gives you the chance to encounter the end user of what you’ve been working on.

How important is time in your work and what do you feel about obsolescence?

I like a rapid design process, that makes the most of the intuitive aspect. For me it’s important that by the time the product reaches the public it’s not already old.

And if you were to end up with a complex project that took a long time?

I think I’d break it up into lots of quick projects! I need this fast rate, and anyway I’m interested in isolating a fragment of memory, cutting myself out a piece of time on which to work with a lasting prospect. I think in fact that value does not lie so much in the time it takes to make something, as in its permanence. This is why, despite designing fast, I don’t create objects destined for rapid obsolescence, quite the opposite. I always start out from a memory and transform things without tying them to a particular moment in history. Sometimes I’m not perfectly in step with my time: I realize I’m getting too far ahead and that it might be better to put the brakes on a bit.

By Collection, Gentucca Bini, 2010.

How did you start?

The first show of my accessories was in 1991, when I designed a hat that held an enormous picnic for an exam in set design at university. I immediately thought of exhibiting it. I was 21. The exhibition at which this unique hat was presented got a certain amount of coverage in the press, and from there I started to design accessories for major brands.

But was your idea to make a product, to provoke or to propose a line of research?

I didn’t want to present a product, but ideas, in other words my creativity, without any commercial aims. The easiest point on which to design something that would have no practical utility was the head, and I concentrated on that. For me designing hats meant not being constrained from the viewpoint of production and functionality, and using the head as a showcase in which to display ideas. The head is a pedestal with an immense amount of space on which to work: if you wanted to you could build a house on it! And presenting myself in that way cost very little: you could show just one hat, and immediately attract a lot of attention. And that’s how it went.

Was it difficult to exhibit the first time?

No. I remember that I organized the exhibition with some friends at the Ponte delle Gabelle, a place leased out by the municipality, where a space cost just 6000 lire a day. In reality, in my life the fewer means I’ve had the more ideas have come to me. We invited all the journalists we knew, and they started to publish our works. In short it was an operation of marketing and for years I focused on this aspect.

When did you start gaining experience abroad?

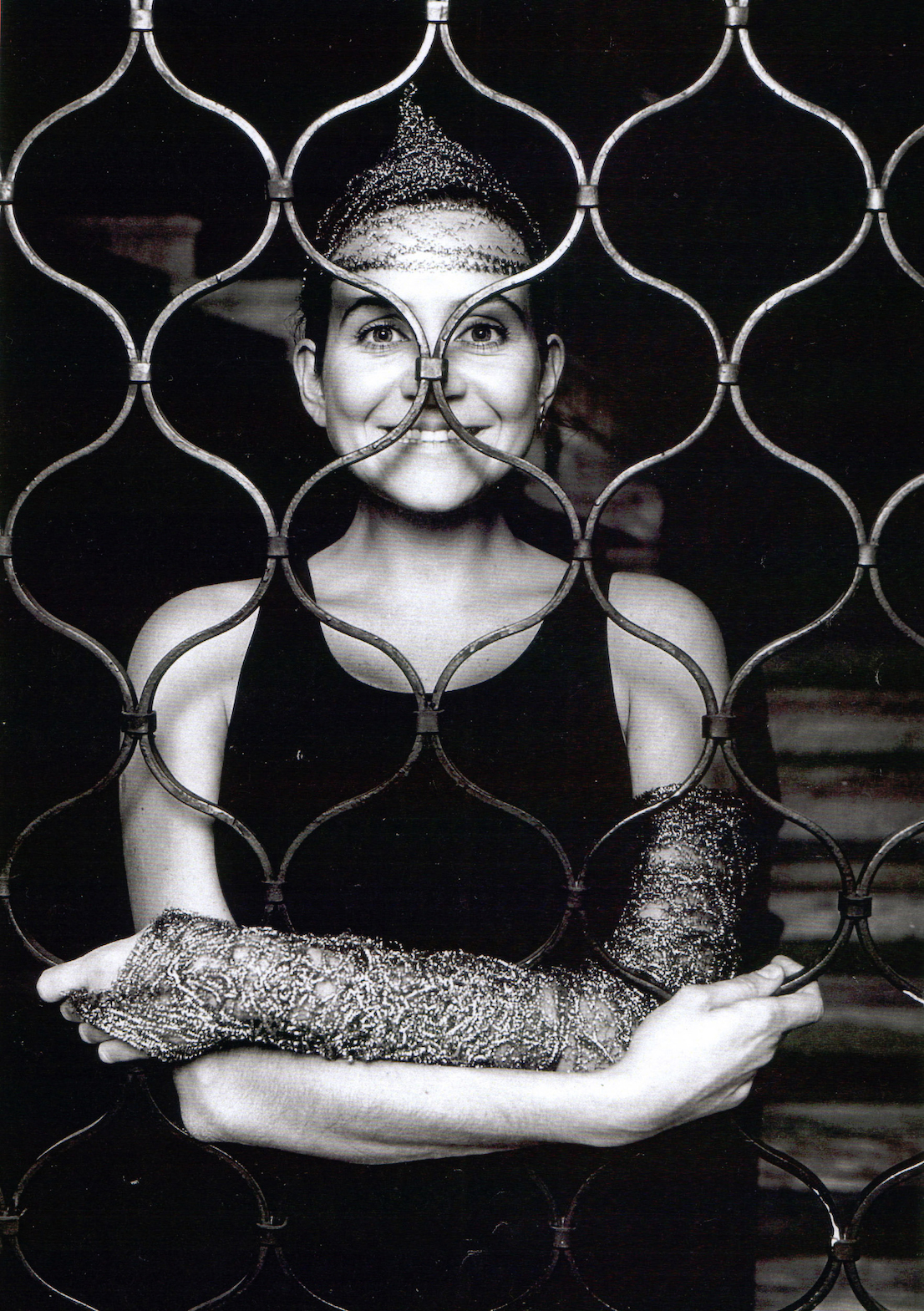

Between 1995 and 1998 I was an assistant at Vanity Fair when it was edited by André Leon Talley, who is now the fashion editor of the American edition of Vogue. André was very good to me. Probably he took me on as his assistant precisely because I wasn’t at all overawed by his fame in the fashion world. He rather liked the simple way I had of proposing my things, and I ended up acting as his assistant on all the photographic features of Vanity Fair and Vogue that he did in Paris. Then through him I met Karl Lagerfeld, to whom I presented myself with my book of leopard-print plush in which I had slipped the Cappellinox, a hat made out of a pad of stainless steel wool, the kind you use to scour dishes. I had designed it for the Milan Furniture Show, where I had put myself on display seated on a chair with this hat on my head and in a setting completely lined with hundreds of these scourers (which I had called Ambientinox). When Lagerfeld saw it, he commissioned me to make a series of them for the next show that he had to do with Chanel. After that Bluemarine, Ferré and many other designers started to call me. I was 25 and in the meantime I went on studying architecture.

Gentucca Bini, Cappellinox, 1997. Photo: Gianluca Bianchi.

Then you passed from the head to the whole body?

In 1997, in Florence, the clothes that my grandparents had made with Fontana, Baj, Del Pezzo and Pomodoro were shown at the big Art and Fashion exhibition curated by Germano Celant and Franca Sozzani. I wore one of those dresses, a model that had never been seen before, to the opening. An enthusiastic visitor asked to buy it and I said that it was not for sale. But this gave me an idea, and I started to think about proposing those clothes again, something which in fact could make sense even for the contemporary market. So I made them again, vacuum-packed them and put them on sale in the bookshops of the museums that were exhibiting the originals. I still remember the time when, after making the clothes, I went to my local delicatessen to get them vacuum packed and then set off for New York to propose them to the curator of the Guggenheim. Back in Milan, I immediately reinvested the proceeds of the sales in a vacuum-packing machine, which has become a great passion of mine.

I recall an invitation to an opening which included a vacuum-packed appetizer!

Yes, it was at the Ritz in Paris for a collection of high fashion.

And after that?

From 2006 to 2009 I was creative director of the Romeo Gigli brand. Designing someone else’s brand is fascinating, because you connect up with a story that’s different from your own. At the same time, though, it’s a fairly absurd undertaking: it’s like asking a writer out of the blue to write novels like those of a certain author, in the same style. The experience at Romeo Gigli was a formative one that I would certainly do again, but perhaps with a more critical, if not downright polemic attitude toward this mechanism.

Gentucca Bini for Romeo Gigli, Fall/Winter 2008/2009.

What do you think it means to be a fashion designer, and when did you realize you had become one?

When I started to present each single piece, and to build a show around it that would tell its story. Both in order to communicate it, and to have a feedback from those who see it for the first time. Which allows me to continue along my road, but paying attention to what others think of my work.

What advice would you give to someone starting out in this profession?

I think it is important not to take yourself too seriously. There are a lot of young people who come to me as interns, and when they arrive it’s as if they had no “grasp of the profession.” They see fashion as if it were a visual application to be tacked onto something that already exists. Sometimes I note a kind of self-importance in wanting to be a fashion designer rather than to do this job. The point for me is not designing a pink skirt, but making a pink skirt, because this has a design behind it. I think that to become a fashion designer you have to design, to enjoy yourself, to show your professionalism and creativity. Creating a product that will sell requires great skills. It can be a goal but not a starting point, in contrast to what many young people think.

So what does it take to make a product that will sell?

Studying needs, targets, costs, marketing plans. In short, cultivating a whole series of skills that you can’t have when you’ve just come out of school. This is why it makes sense to do internships; otherwise it would be like thinking that someone who has just graduated in architecture is already an architect capable of constructing a building.

How did you come to high fashion and what relationship do you have with such a demanding world?

In 2003 I requested the Camera della Moda [the non-profit-making body that disciplines and promotes Italian Fashion, translator’s note] to be put officially on the calendar and present one of my products. Before then I had held a show in a corridor of the Trade Fair, but without a real audience, just with cutouts and an invitation that had already been scrunched up (and was ready to be thrown away), vacuum-packed of course. In 2004 they invited me to Rome during AltaRoma to put on a performance. I had to come up with something, perhaps stage a show that would be a bit of a caricature of the official shows. I was given a 100-square-meter room in the Auditorium Parco della Musica. I felt I had to something in grand style, but I also wanted to poke a bit of fun at this world. In the end I decided to make just one dress, but an enormous one. Out of this came Un gran bel vestito [“A Really Great Dress”]: some stagehand friends made a wooden dais in the shape of a cake on which I placed four models, each wearing a top from which descended this gigantic skirt that in the end covered all 100 square meters. I asked a velvet manufacturer to print red polka dots of decreasing size on white velvet in order to create a strong impression of perspective and make the dress look even longer. In this way I combined an approach similar to that of an upholsterer, as far as the maxi-skirt was concerned, with a more specifically sartorial intervention in the bodices.

Gentucca Bini, Un gran bel vestito, 2003.

How important is gesture in your work?

It is fundamental. I always start from the gesture. The fact that a designer is able to modify the actions of people with an item of clothing or an object or a setting is the most fascinating aspect of the profession. I like to start out from the memory of a garment and introduce an error into it that is able to trigger a gesture that the person might not have ever made of their own free will. For instance, I made a collection of perfectly tailored dresses, except that on one side they fell loose, with no seams. The result was to force the wearer to pull up the shoulder straps, in an extremely sexy gesture.

Perhaps a bit uncomfortable too.

I’ll give you another example. I was in Madrid recently, where I visited the oldest store selling alpargatas, the famous espadrilles with rope soles. I found a pair made of braided straw, consisting of a very simple weave without a vamp. Practically speaking, a sole with two strings and a couple of little strips. They weren’t for sale, but I persuaded the owner to give me them and I can assure you that with these really flat shoes, made of nothing, I walk in way I wouldn’t even if I had on a pair of shoes with 5” heels! These shoes seem to be designed to modify the way you walk, and make it more sensual, even though that was probably not what was intended. I believe that elegance lies more in the action of the wearer than in the clothing in itself. Everything works if the clothing creates the gesture that makes you move in an elegant way. Like with those shoes, which are beautiful because of the effect they produce.

Tell me about your latest projects.

I’ve just finished a very beautiful project with Yoox.com, a collection of sweatshirts. The staff at YOOX is made up of very competent people, attentive to what is going on in the market and respectful of the ideas of the designers they work with. They know how to connect the creative side of the designer with the commercial one, in a really effective way. The main problem in fashion today is linked to the relationship between quality and price, in the sense that the price of the product on the market does not depend on its real quality. With YOOX, though, by eliminating a series of intermediate steps and their markups, you’re not forced to renounce quality to keep a product within a certain price range. And then I have created a new collection of work clothes, involving nine friends who have the most disparate jobs. I took workman’s overalls, including a 19th-century one from Les Halles: serious uniforms that are suited to the jobs of those who are going to wear them. For example, one of the participants is Massimo Torrigiani, the new director of the Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea, and he wanted there to be one pocket that could hold at least an Adelphi (a large format paperback book, translator’s note). Another artist friend, Roberto Coda Zabetta, felt he needed to carry a paintbrush around with him, while the architect Luca Cipelletti wanted a tailored overall with lapels and buttons. These designs were worn by the people they were made for during the Fashion Week in Milan.

Gentucca Bini, The Charme of the Uniform, 2014.

Gentucca Bini for Gucci, Spring/Summer 2013.

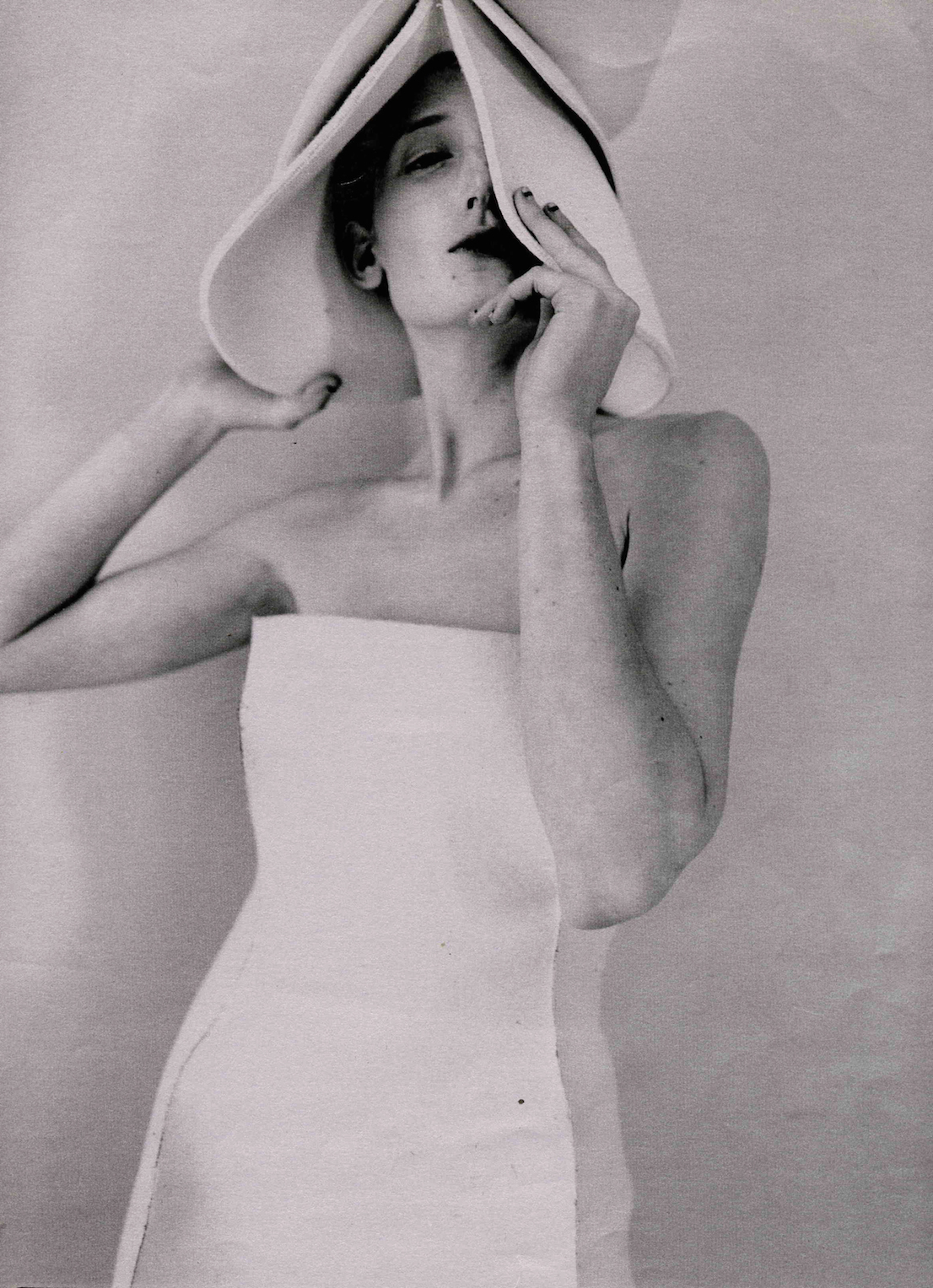

Gentucca Bini, 1999.

Gentucca Bini, Fontana, sottovuoto.

Gentucca Bini for Yoox, 2014.

Gentucca Bini for Yoox, 2014.

Gentucca Bini for Yoox, 2014.

Gentucca Bini for Yoox, 2014.

Gentucca Bini for Yoox, 2014.

Gentucca Bini for Yoox, 2014.

Gentucca Bini for Yoox, 2014.

Gentucca Bini for Yoox, 2014.

Gentucca Bini for Yoox, 2014.