2 March 2016

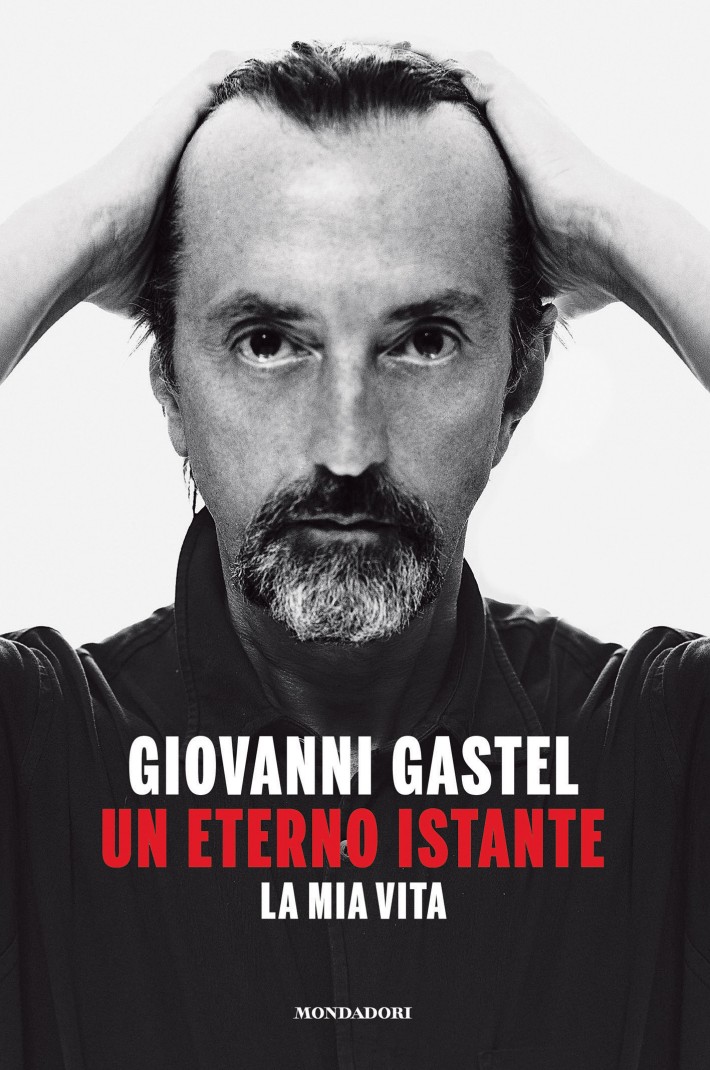

“Think of something extremely beautiful.” He looks at you, strokes your forehead, peers down at you from all of his six feet three inches. “Nothing indecent, I’m a gentleman.” Giovanni Gastel, one of our greatest fashion photographers, is like that. In his Milanese studio on Via Tortona, with music playing, two assistants circling around him, a bookcase full of memories. It’s impossible to use the formal mode of address with him. A little earlier, rolling his rs and with the camera in his hand, he had explained: “I will make you an icon, it will be you inside me and then again you outside me. I’m not your mirror. What I’m trying to do is to portray you as I feel you, through my joys, my moments of sadness, my sorrows. And about this Barthes was right, photography is more of an aspiration to death than to life. I’m attempting to restore you to your archetype.” Born in Milan in 1955, the youngest of seven children, Gastel is the nephew of Luchino Visconti and, torn between writing, poetry and theater, chose photography in the seventies. After working his way through the ranks for a long time, he met Carla Ghiglieri, who introduced him to the fashion world. He took pictures for Mondo Uomo, Donna, Vogue, W, Elle, Vanity Fair, Amica and Glamour. Then came advertising campaigns for Dior, Krizia, Trussardi, Nina Ricci, Tod’s, Versace and Acqua di Parma. Endless publications, awards and exhibitions, like the one-man show at the Triennale in 1997 curated by Germano Celant. In 2002 he received fashion’s equivalent of the Oscar for photography at the event known as La Kore, Oscar della Moda. Last September Electa Mondadori published his autobiography Un eterno istante, written over the course of a month on the island of Filicudi.

Are you happy with how the book is going?

I didn’t expect it, the first edition has sold out. Then again, I always thought I would write sometime in my life, it was my first passion.

At the beginning of the book you talk about the theater though.

Theater was my entrée into the world of art, at the age of twelve. I remember that my sister wrote me a serious letter, telling me that her company needed an actor. I ran to my mom, a Visconti, who surprised me by telling me: “Not only can you do it, but you must.”

The Gastel family, Sperlonga, 1963-64.

And what was your father like?

My father was an industrialist of the middle class, a very angry man. When at the age of seventeen I decided to become a photographer, he told me I wouldn’t get another penny out of him. He gave me a comb and a mirror: “Since you’re going to take passport photos, at least your client will be able to tidy himself up.” But then he started to come to me to take his photo: “I have to make my passport,” he would tell me on the phone before coming by. But he was always happy about it, and used to say so to my brothers: “He’s earning a lot of money, Giovanni. While you lot are still at university.”

What was it like being a photographer in the seventies?

It was fashion, along with the time, that made the profession appreciated. When I started, in the mid-seventies, the photographer was a bit like the cobbler. If you wanted to be taken seriously you had to be a street photographer: the kind in the cathedral square with the pigeons, if you get my meaning.

And why did you start doing it?

Because I had a girlfriend who pestered me. I wanted to write, but she found that boring. Actually, though my poems were often dramatic, she liked hanging around with photographers much better.

And have you ever regretted not becoming a poet?

The history of Italian poetry shows that no poet has been able to make a living from poetry, not even Montale, who worked as the music critic for Il Corriere della Sera. No one reads poetry.

Giovanni Gastel, 2000.

I don’t agree.

Selling five hundred copies is considered a publishing success, out of a population of sixty million. I go on publishing them too, but who reads my poems? We read them among ourselves. If I say “I’m going to read you a poem,” everyone runs away.

But poetry is intimate, it shouldn’t be read to others.

School has taught everyone today to hate poetry.

Perhaps our decline is the fault of the lack of poetry, wouldn’t you agree?

For sure. Paradoxically, the poem, as structure, would be very well suited to today’s world. Because it’s short, concise, perfect for an age in which no one has time to read anymore. But I knew that I couldn’t live off poetry and I would have to do something else.

Photography?

Don’t get me wrong, for me photography is a wild passion. I wouldn’t be able to live if I didn’t take photographs. Even last night I came to the studio and took one, I had no choice. If I take pictures I’m fine, if I don’t I feel bad. It’s a matter of necessity. If I don’t do it I come into conflict with myself.

Carla Erba Visconti di Modrone, Giovanni Gastel’s grandmother.

You say it as if it were a sexual drive, an erotic need.

If there’s no seduction, there’s no photography. I have to be seduced by and seduce the person whose picture I’m taking. For 1/125 of a second. Everything is reset to zero in the instant of the flash. Everyone thinks that the eternal moment is the photograph, but it’s the going off of the flash, that instant of absolute whiteness and total cleanliness. Then there is a new world. I’ve even learned to eliminate the sense of time.

How?

Everything that I’ve done counts for nothing, everything that I will do is not necessarily going to happen. So I just stick to the present. Now I’m with you and the only reality is you.

They ought to write that on a T-shirt.

I’m totally yours, but you have to be totally mine. It was something my mother always used to tell me: “If you talk to somebody, whoever it may be, give him your complete attention. Cut yourselves off from everything and from everybody and, for the time you spend with him, be just his, otherwise you’re not talking to each other at all.”

Moving on to your works, I’ve heard that you will be photographing the people and the institutions that have “made” Milan for the publishing project You Are Milan. Not just well-known faces, but also the flower seller, the barman, the window cleaner and so on.

It’s a project I believe in, I like the underlying idea that without each of us, in fact, the world would not be there. Or rather, this world would not be there. As a keen reader of theology I’m reminded of a beautiful reflection by Pascal on our condition as women and men.

What does he say?

That we are all struggling to understand the meaning of life, tomorrow. But what we ought to be thinking about is a tapestry. We are inside that tapestry, lost in the meaningless tangle of its knots. But when we are on the other side, after death, moving away from it, we will be able to see the pattern. If even a single knot were to be missing, the tapestry would be incomplete.

Do you believe in God?

(Reflects for a few seconds) Yes.

Is God a woman or man?

I can’t say, I hope a woman. The law of love is more feminine than masculine. I have a very deep relationship with religion, but I don’t have an unshakable faith. I waver.

Krizia, 1987 campaign. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

But isn’t that what faith is?

In reality, it ought to be like that of the old women in church. It often happens that when I go to church, I relax, I feel the embrace. I could let myself fall backwards, because I know someone will catch me. In fact I often yawn. Everyone thinks I’m bored, but that’s not the case. I’m so relaxed that I feel great.

Usually people recommend restaurants, but I’ll ask you what church you would recommend in Milan.

San Gottardo, behind Palazzo Reale. It was the historic church of the Visconti family, before that madman Gian Galeazzo began construction of the cathedral. A delightful church.

What relationship do you have with Milan? What does it mean for you to be a Visconti?

It’s a city I love, even though I lived in Paris for twelve years. Milan has never succeeded in becoming a European capital, but now it is getting back on its feet.

What do you like about it?

I liked the Expo a lot, I love the new districts, Piazza Gae Aulenti. The city has begun to make plans again, it is looking to its future.

Are you an optimist?

Above all I’m a melancholic. I’ve always thought I had elegance in me, as a moral value. It is the key word of my aesthetics. Elegance is many things: loving women, paying taxes.

What do you mean?

A true gentleman pays his taxes. It’s shopkeepers who don’t pay their taxes. You’re not born a gentleman any longer, you become one by the way you treat people, women, the state. As well as to elegance, my state of mind is linked to melancholy. I wrote about it in a poem, I feel like a castaway: “Landing in this age like a castaway in a foreign land, I’ve measured the territory and learned the natives’ tongue.” This poem took shape by itself, a bit like a photograph.

Let’s say that Giovanni Gastel is a blend of poetry and photography.

They are both an expression of a need, they are born out of a state of latent unease. A bit like dreams.

What do you dream about?

I often have complicated dreams of which I have no memory. Sometimes I resolve situations and understand important things. When we die it will be a bit like dreaming. There is a new theory of quantum physics, a subject that has always fascinated me. Some physicists are very close to demonstrating that the state of consciousness is disconnected from matter. So the survival of the soul has a sort of scientific underpinning. There is a self-generation of consciousness that lies outside matter. Our thoughts will be generated independently forever even when the matter is no longer there. This would change the destiny of thought, even on the religious plane.

Trussardi Jeans, 1990 campaign. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

What comes after death?

I have the impression that everything will be simpler. My idea is of a poetic nature. I don’t have anything against this world, but I don’t really feel I’m part of it. That’s why I’ve chosen to shut myself up in the cellar and re-create the world. I’m just not able to belong to the one outside. Like Pierre Drieu La Rochelle’s Will O’ the Wisp, the story of a man who can’t get on with life. In the end he shoots himself, in order to reconcile himself at last with things. Drieu La Rochelle, along with Céline, has been forgotten because of his association with Nazism. But there is something my uncle Luchino always used to tell me.

What?

Never judge an artist by his life, but by his works. It would almost be better not even to know what an artist looks like.

What relationship did you have with your uncle? You talk about him in the book and thank him.

I really loved him, he was an extraordinary man. Unfortunately many people today see Luchino as a sad clerk, a homosexual, like von Aschenbach in Death in Venice. But my uncle was a revolutionary, communist, a beautiful man, a winner. He used to go dancing at the disco every evening. We are the last people alive who can say what he was really like. He spoke of dying societies because he was interested in the one that was being born. He believed deeply in the emerging society, he wasn’t gloomy. I am much more so.

And do you believe in emerging societies?

Growing older, I have realized that the society which I thought I belonged to has never existed. I thought there was an aristocratic, elegant world, but when I got to know it I found it was full of dickheads, like all of us. My world is an invented one.

How is the world of fashion?

It has been my patron. When I started to design the world, fashion was perfect. I saw the birth of the idea of communication for fashion when the admen shunned it. I sat with Flavio Lucchini, as a very young man, at work tables where all this was discussed. In a revolutionary move, we had decided never to speak to the final consumer. Communication for fashion—I’m talking about clothes, not accessories—creates a world of reference. In essence, we were saying: “If you want to be part of this world, made up of wealth, elegance, beauty, a world that does not in fact exist, then you have to buy that kind of panties.” Brilliant, no?

Donna, first issue, March 1982. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

To me it looks like a mirage: to be like a god, you have to dress like a god.

We are that world there: parties, riches, elegance. It’s an illusion that is used to sell things. And it was precisely this that interested me in my research, because I too was creating a world of reference made up of harmony and beauty. And then they have been my sponsors all my life.

Is there is someone in fashion with whom you were particularly happy to work?

As a young man Nicola Trussardi, because he was aiming at my own world. He said he wanted to create an intelligent, cultured, elegant society. But I had great fun with them all, from Versace to Krizia.

What was your relationship with her?

Wonderful, my little Krizia. She picked me in 1981. We did an enormous amount of work together, in practice up until the time she sold the business. In her anthological exhibition she said something beautiful about me. She spoke of an experience characterized by an almost mediumistic affinity.

The absence of the fashion world from her funeral caused a stir.

I’ll tell you how it went. Our world, that of fashion, is a game and should not be confused with life. It’s like Monopoly or poker, and when you play obviously you want to win. But you know that at the end of the game you put it away. I too was sorry that nobody was there. But it’s Monopoly, if you don’t have hotels any more, then no one gives a shit.

How sad.

It’s terrible, but fashion people know that it’s Monopoly. And Heaven help you if you mistake it for real life. Success breeds success, but you have to know that these are the rules. In Monopoly you may no longer count for anything, even if in real life you count a great deal. And for me Krizia was fundamental in real life.

Jovanotti, 2011. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

At the beginning of your autobiography, you list all the performers. Like they do in plays. As well as Krizia, there was really a lot of people who played an important part in your life.

I grew up and lived in a generally loving climate. Perhaps it’s my way of being, my looks, but for me they are all adorable, and I really feel that way.

That makes you sound like a goody-goody. Tell me something nasty. Go on, give it a try.

The world has been very good to me, everything has gone well. Why should I? I’ve been lucky. I was born into a fantastic family, I’m six foot three, I’ve had all the culture I wanted, given that what are museums for others were home for me. I’ve played tennis and become a champion. I’ve ridden horses. Women adore me. I chose to be a photographer and became very good at it. I’ve just turned sixty, I have the same birth sign as God. And I should be pissed too?

It’s not just luck.

Luck is not enough, you have to put your life into it. Picasso used to say that genius is eight hours of work a day. You have to have a bit of luck, but then you have to study, read, apply yourself. My wife Anna say that for thirteen years I never came home before two in the morning. Saturdays and Sundays didn’t exist.

Half fortune and half virtue.

I’ve always felt that fortune gallops alongside me, as Caesar put it.

What advice do you have for young photographers?

Work on what makes you different, your work has to have something of you in it. Choose a word that represents you and base your aesthetics on that. Young photographers write to me on my Facebook page: “I’m a modest wedding photographer.” Modest my ass! Recently, I photographed the wedding of Michelle Hunziker and Tomaso Trussardi.

And you started with weddings!

There are horrible fashion photos and brilliant wedding photos. Nothing changes, it doesn’t matter what you are doing, but how you do it. It can be a brooch, a top model, a wedding, a pebble. I have to seduce the pebble, and the pebble has to seduce me.

How much does one of your photographs cost?

Ten thousand euros, or, as I often do with friends, I give it to you. Giò (he calls his assistant). Will you prepare a set for me?

Maschere e spettri, Palazzo Reale, Milan, 2009. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

Monica Bellucci, 1999. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

Roberto Bolle, 2013. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

Bianca Balti, 2015. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

Elisa Sednaoui, 2015. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

Krizia, 2006 campaign. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.

Krizia, 1985 campaign. Photo: © Giovanni Gastel.