16 May 2013

One of the most visionary fashion designers of our time, a poet of ancient fables hidden under piles of recollections and suggestions of the memory, Antonio Marras, born in Alghero but a nomad in the world, succeeds every year in enchanting us with his creations. He has told Klat his story, that of a man “given over to rags.”

From shop boy to fashion designer: what were the stages in this progress?

I grew up in the midst of fabrics, in the family butigas [“workshop”], but I was attracted by other things: cinema, art, dance. I’m a very curious person, it is hard for me to rein in the Ulysses I have inside me. My imagination has always been a chaotic jumble, just like my drawing table: covered with newspapers, books, sheets of paper and doodles. Then the sudden death of my father, the shop to be kept going, the continual work with and in the midst of rags. Until I arrived at my first collection, a moment of great confusion and disorientation that my wife Patrizia helped me to get through. So in 1987 Piano Piano Dolce Carlotta was born: a homage to my great passion for the cinema and for a legendary actress, Bette Davis, splendid in her poignant performance in Robert Aldrich’s movie Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte, which we chose as title of the show.

It was a success.

I can still recall the sensations that flooded into my mind: incredulity, amazement, almost bewilderment. To tell the truth, they are the same sensations that I have today, before and after every show! I haven’t changed since then.

And then the first high fashion show.

For ten years I worked on a line that was a great commercial success, but didn’t bear my name. I was already starting to get bored. Then something gave me a flash of inspiration: a meeting with the artist Maria Lai, who appeared like a fairy godmother. And so, with the support of Maria and of Patrizia, whose presence has left its mark on my life from every point of view, I presented my first collection of haute couture in 1996, and the first of prêt-à-porter in 1999. They were moments of great enthusiasm and energy.

The canons of your aesthetics are recognizable, but hard to categorize. Each collection has a theme that takes its cue from a phrase, a song or a historical figure. In most cases, a woman.

My creations are born out of what I am and my experience. Each collection tells a different story: there is no recurrent theme and not even a stereotype of reference. Feminine reality is variegated, many-layered, multiple, and in a dress—in its signs, in its forms and, above all, in the story it tells—each person has to be able to recognize herself and discover her identity. When I design I’m inspired by fascinating women, like Pina Bausch, Silvana Mangano, Isabelle Huppert… I imagine my clothes worn by free women, able to realize their dreams and desires. Out of this came the collections dedicated to Maria Lai, Ligazzos Rubios, Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Eleanor of Arborea, Charlotte Salomon, Paska Devaddis.

What are your sources of inspiration?

They are many, of various kinds. Sardinia, above all. Dark and discreet, one and multifaceted, vital and creative, it is a place filled with complexity, contradictions and conflicts that have been dragging on for millennia. But it is also a place drawn by the currents of modernity. Mediterranean, Phoenician, Carthaginian, Byzantine, Arab, Catalan and French influences have made us what we are, in our language, our thinking and our dress.

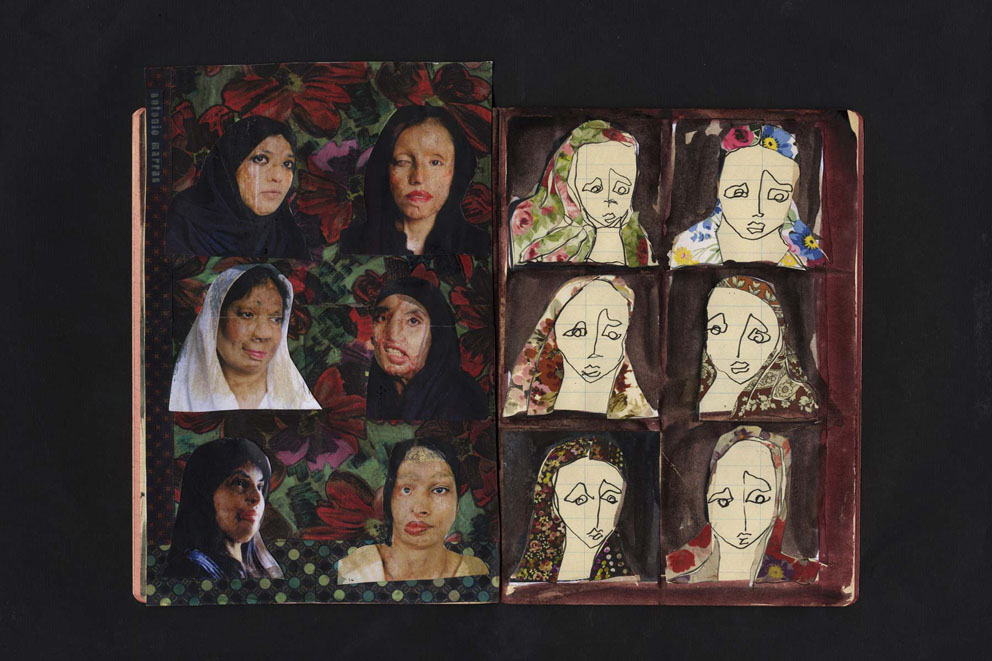

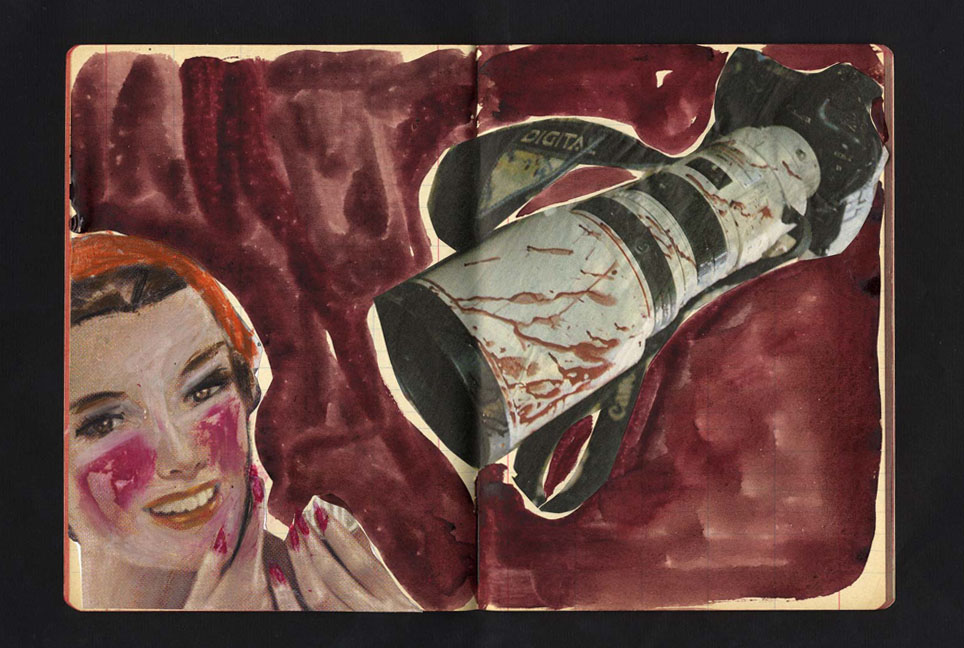

Antonio Marras, Archivio Provvisorio, Biennale di Venezia, 2011.

Antonio Marras, Archivio Provvisorio, Biennale di Venezia, 2011

Music, books. What are your favorites?

I listen to all kinds of music, from classical to pop. And I read a lot on journeys, when I’m not scribbling in some notebook. Recently I read La musica è leggera. Racconto su mezzo secolo di canzoni by Luigi Manconi, with a fine introduction by Sandro Veronesi, and Emanuele Trevi’s Qualcosa di scritto. But my favorite book, the one I read over and over again, is Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology: hopeless lives turned into poetry.

You travel a lot.

In my dreams I’m a nomad who is always thinking of his Ithaca, Sardinia. I like to get to know places I’ve never been to before, but I also like going back to where I’ve already been. I’m always very happy to return to New York, a city that fascinates me and that I would choose as a second home. And I’d like to go back to Vietnam, with its fantastic worlds.

Your work as creative director of Kenzo brought to light new aspects of your creativity, but it also meant you had to deal with the ideas of another fashion designer.

Working for others means putting yourself on the line, being open to an encounter. And it often signifies taking rough and tortuous paths. Working with a brand that helped transform the fashion of the second half of the 20th century with pioneering cuts, unmistakable patterns and colors, has been very important for me, as well as fascinating. I share Kenzo’s cultural curiosity, his unbridled intellectual nomadism, his liking for putting people off their balance though the use of colors and the mix of forms. I reinterpreted prints, fabrics and colors, thoroughly exploring the traditions of the East, mixing and fusing them with Western ones. I compared Sardinian dress with the kimono, going on to transcend and modify them, venturing into new scenarios. I deliberately created chaos, only to represent it with order and harmony.

Sfilata Kenzo, primavera/estate 2006.

Your shows are always eagerly awaited in Milan, as are your invitations, which are small artistic creations in their own right.

The show is the culmination of months of hard work and is the stage on which my world lives. It only lasts a few minutes, but invitations, titles, scenery, texts and music are closely bound together in a subtle play of allusions and parallels. Someone has written that in the invitations “scents, colors and sounds respond to one another like echoes that merge in the magical and profound unity that is the show.” All true. And here lies the brilliance of Paolo Bazzani, designer of the invitations and the scenery.

Where do the themes of your shows come from?

It’s hard to say how a creative process is born and develops. I trust my intuitions. Nothing is ever established beforehand and everything can be changed along the way. I have the impression that the collection is something glimpsed briefly, out of the corner of the eye, which is then turned into something else that intrigues and illuminates. But inspiration and intuition are not enough, a lot of work is needed.

I know that dream plays an important role in your work.

The dimension of dream is a fundamental part of my life and my activity. Even when I look at reality in a didactic way, the visionary steps in at once. I look for unexpected relations, the most vivid aspects, and so out of reality spring images that evoke other dimensions and other inspirations. “What is life? An illusion, a shadow, a story. And the greatest good is little enough: for all life is a dream, and dreams themselves are only dreams,” said Calderón de la Barca. But Shakespeare too speaks of dream in The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I’m still moved by the memory of the day on which Luca Ronconi asked me to make the costumes for his production of Shakespeare’s Dream.

Sogno di una notte di mezza estate di William Shakespeare. Regia Luca Ronconi, 2010. Costumi di Antonio Marras.

Sogno di una notte di mezza estate di William Shakespeare. Regia Luca Ronconi, 2010. Costumi di Antonio Marras.

You’ve chosen to live a long way from a big city.

I’m convinced that the best way to understand your own time and your own world is to place yourself at a certain distance from it, give yourself a perspective from which to observe and study it. Much of my life is lived on the periphery, in a small town on an island in the middle of the Mediterranean. In Alghero I have my house-workshop, in which the boundaries between the private and work are very blurred. Here is the motor from which everything starts.

Is there is an object of which you are particularly fond?

Yes. It’s a strip of a crimson fabric that reminds me of the tapes used by people setting off on a journey to tie up their suitcases, bundles or bags. For me this ligazzo rubio is a thread that knots things together firmly, that binds affections, feelings, emotions, that resists wear and tear and keeps what leaves fastened to what stays. I give it to a few close and trustworthy people, as a concrete expression of the bond of understanding that unites us and makes us “one.”

Speaking of Alghero, it is impossible not to recall the lyrics of a famous song of 1986, performed by one of the island’s most magnificent singers, but of Sicilian origin. What is the mysterious charm of this town?

Giuni Russo’s “seaside style” sums up well the Alghero of those years: a tourist resort by the sea, beach umbrellas, swimming offshore. “Alghero,” says Luigi Manconi, “was a place where you could still make sheep’s eyes at someone and watch, from the ramparts, a warm and mythical sunset.” Alghero has a mysterious charm that stems, in my view, from the mixing of peoples. Occupied by the Catalans and then reconquered by the Sardinians, it is a composite, living reality today, one that wants to defend its history, its language, its culture, its territory. And luckily it still has an unspoiled environmental heritage, a landscape of incomparable beauty. The fiery glows of the sun dying behind Capocaccia, the scent of myrtle and Helichrysum, the ambat, the maestrale, the sea…

Thesis and antithesis, person and personality. In the play of contrasts, how does Antonio Marras define himself?

The antithesis, the form, the role, the mask often kill our true being. When I sense this danger, I try at once to avoid it and usually I succeed. At times, though, I have to give in to the personality, which coops up and conceals my true self. But it is only for a moment. Those who are close to me say that I’m pessimistic but sunny, shy and serious but cheerful too, a realist and a dreamer, ironic and thoughtful, little inclined to give in to despondency or to be completely caught up in it. I’m a restless spirit, like the writers of the Sturm und Drang period, beset by romantic yearnings that rack me and drive me on. And then I’m impatient and almost never fully satisfied with myself. Not to speak of my naivety and complete lack of practicality.

What does Antonio Marras’s future hold?

I don’t usually make plans, either in the short or the long term. I’m a fatalist. Rather than of plans I’d prefer to speak of things that I’d like to investigate more deeply, not necessarily in the field of fashion, but perhaps by cutting across artistic boundaries. In my wildest thoughts, I’d like to have a sudden inspiration, a brilliant intuition that would have the force of a slash in one of Fontana’s canvases. I’d like to find the idea that would persuade women all over the world to wear my clothes.

How is your Algherese?

For me it’s my family tongue, the language of my childhood and my sense of belonging. Increasingly often I find myself using words and expressions from it and I’d like to learn to write it. So I am thinking seriously of attending the Escola de Alguerés.

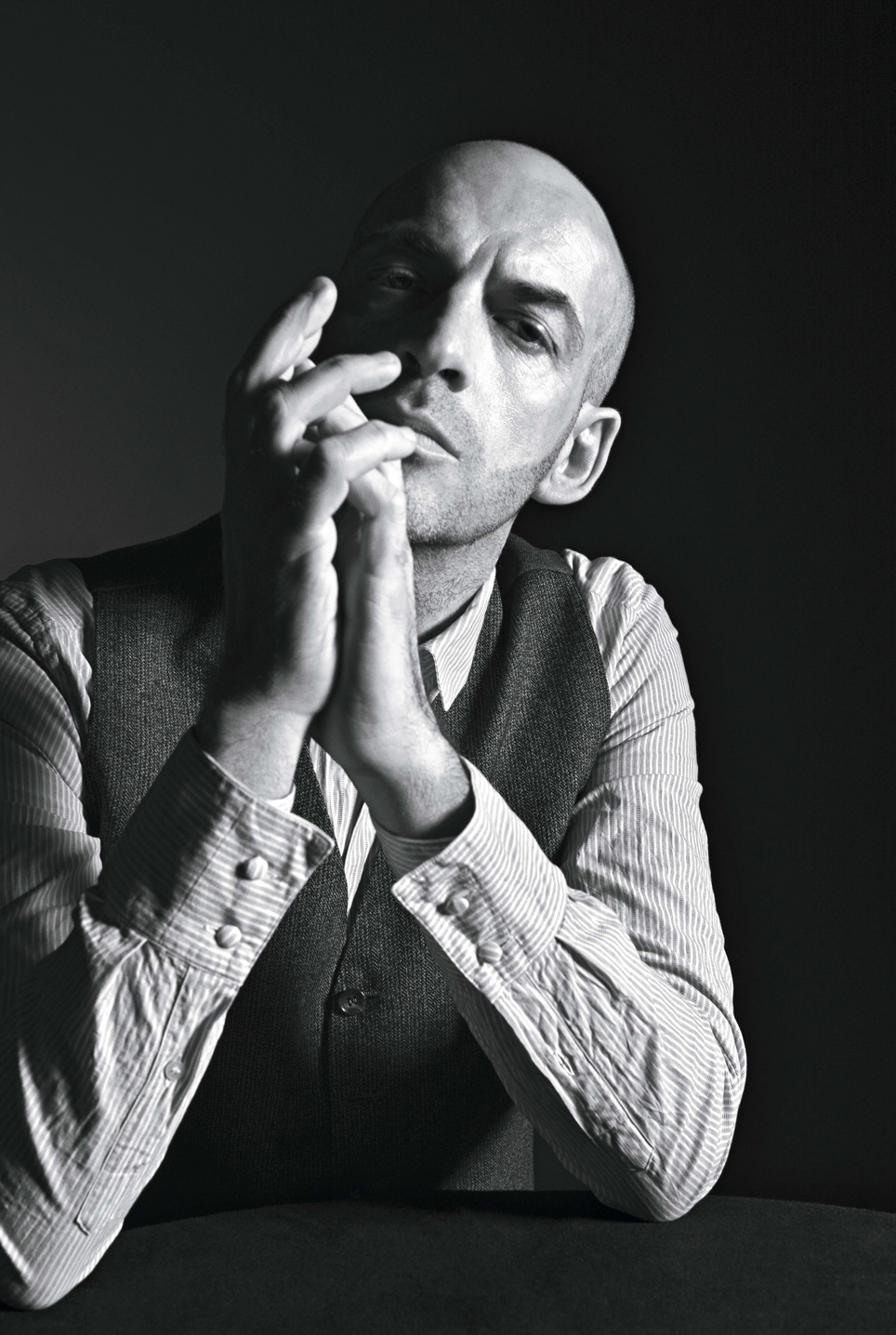

Antonio Marras. Photo: Mario Sorrenti

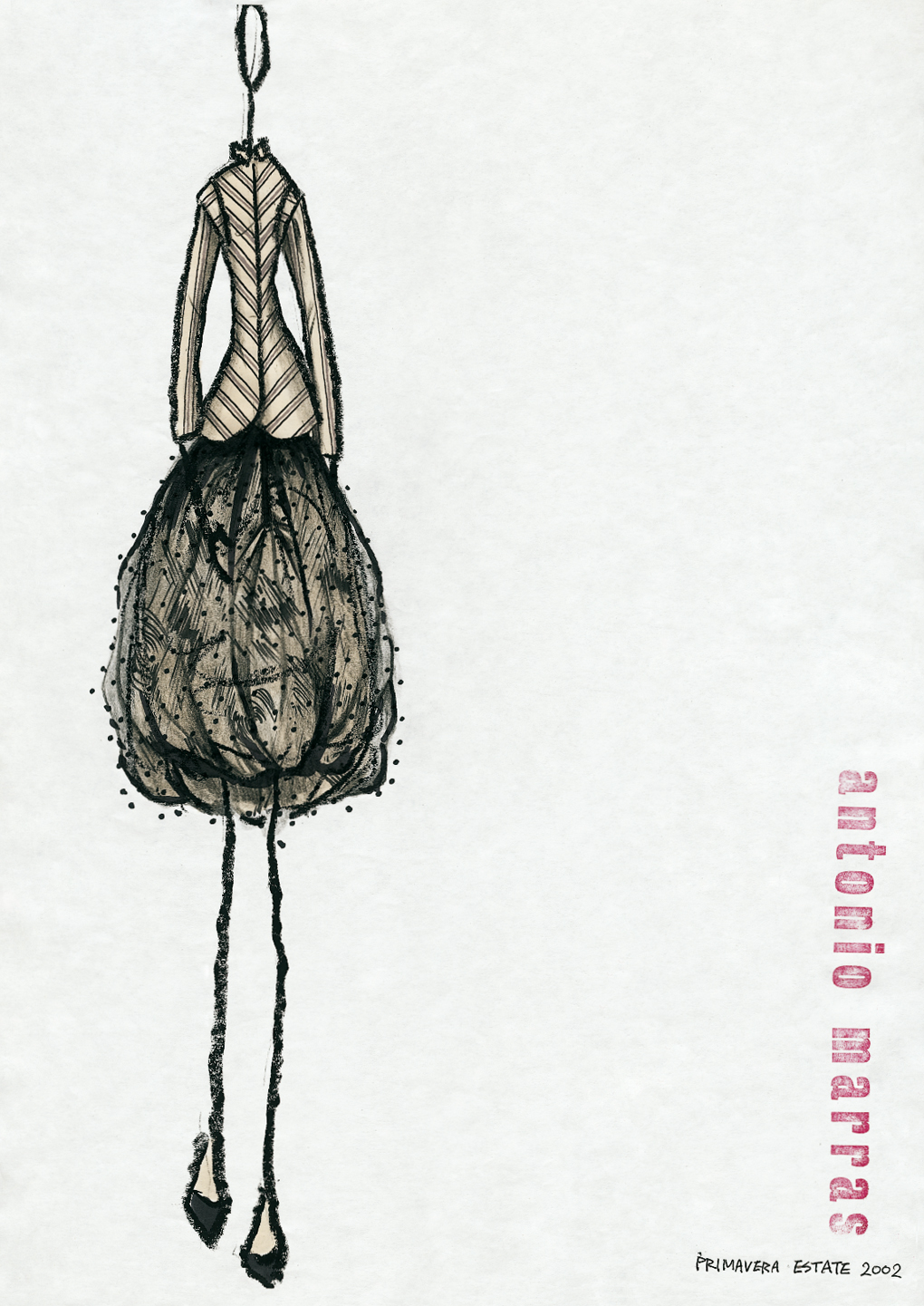

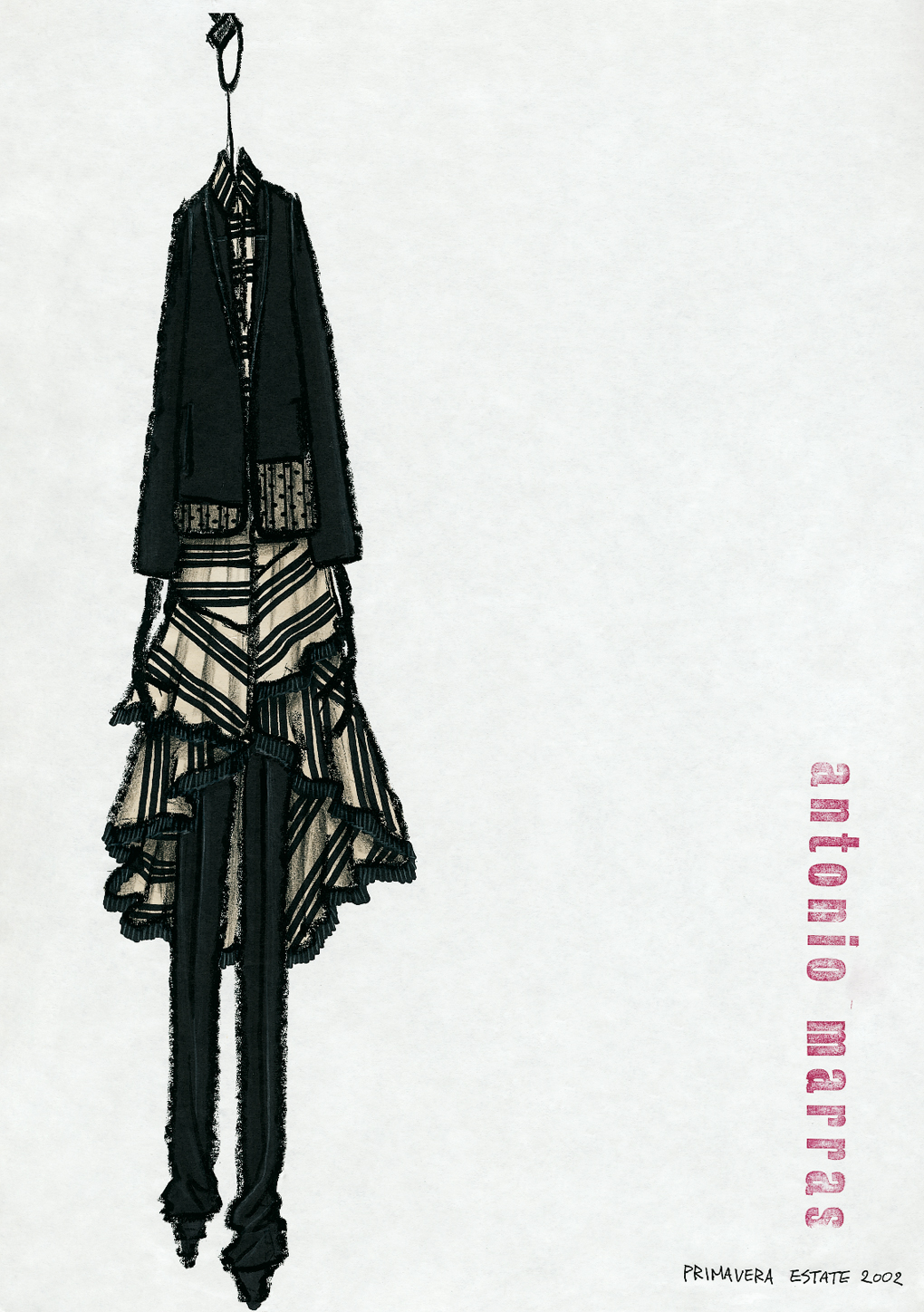

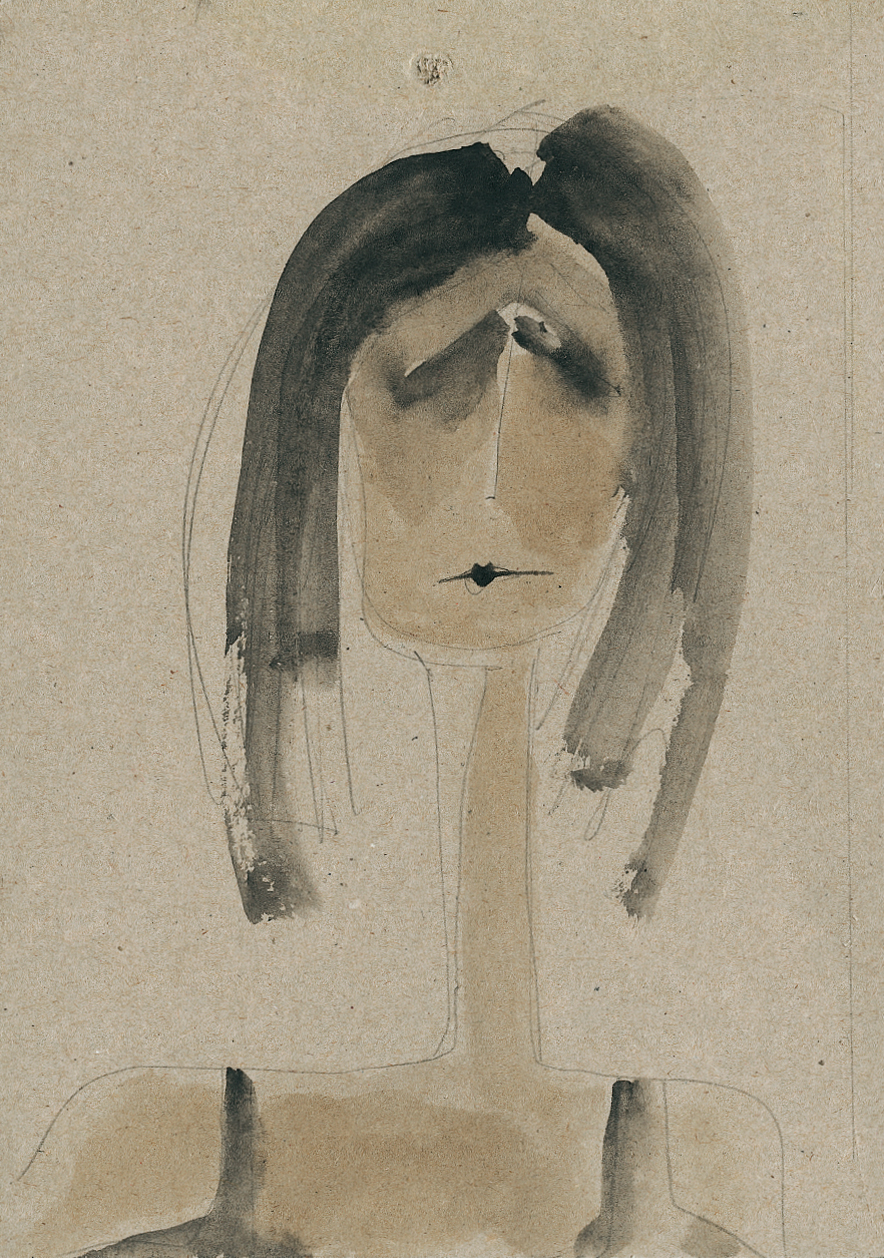

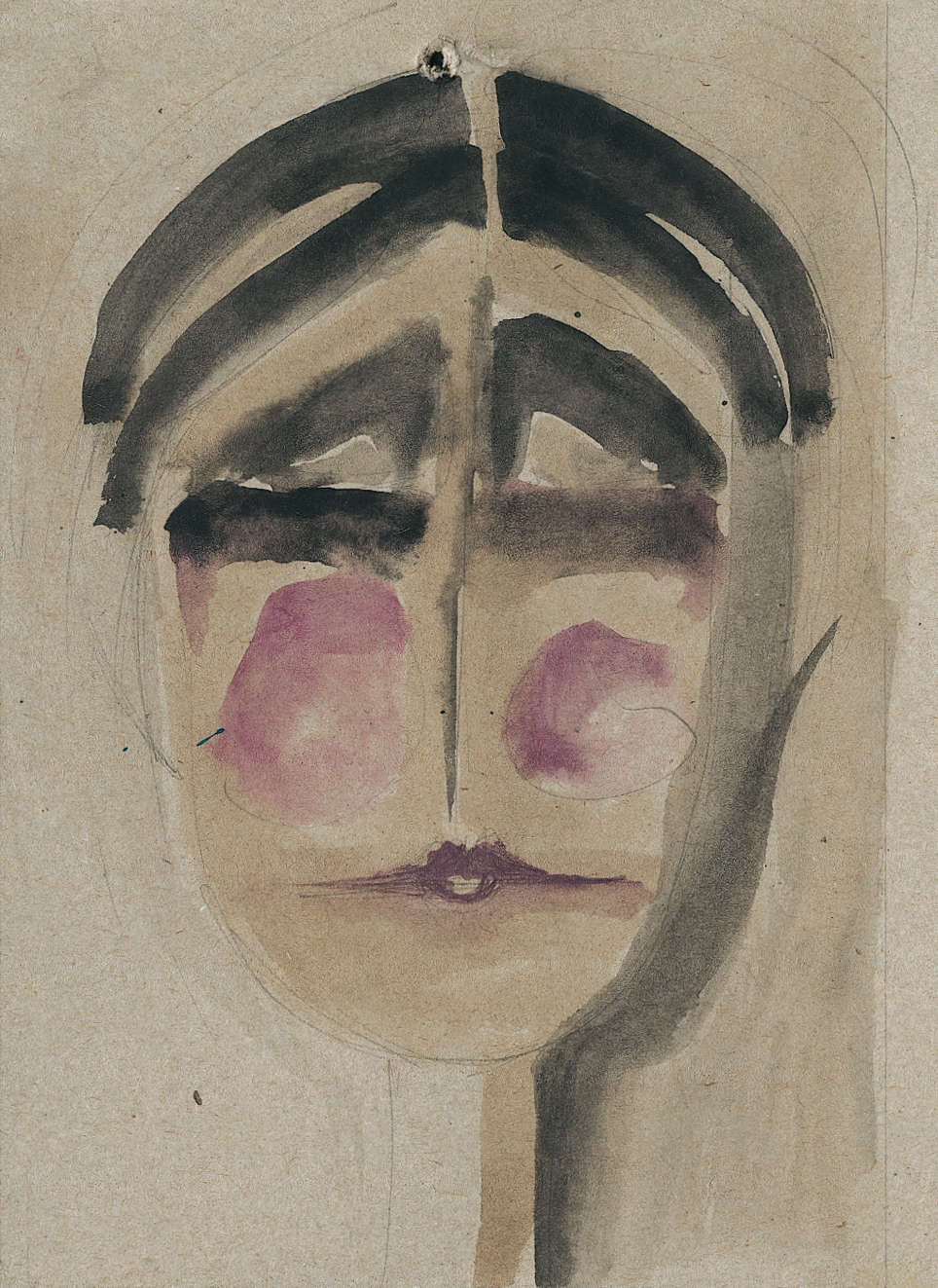

Antonio Marras, Sketches, 2002

Antonio Marras, Sketches, 2002

Kenzo, Spring/Summer 2011.

Antonio Marras, Fall/Winter 2011-2012.

Antonio Marras, sketches 2000-2002.

Antonio Marras, sketches 2000-2002.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.

Antonio Marras, Spring/Summer 2013.