24 October 2016

Music is an element of cohesion, a means of struggle and social emancipation, and the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, set up and run by the Smithsonian Institution, has integrated it into every section of its display devoted to the Afro-American community. A history that is explored to the rhythm of the spirituals sung by slaves, as well as the music of James Brown, Nina Simone, Donna Summer or Public Enemy, which is at last seeing an unalloyed recognition of its fundamental contribution to shaping the identity of a country. Five floors of exhibitions, three of them below ground, tell in chronological order the story of centuries of injustice, conflict and liberation. An uncomfortable testimony to the first chapter in this adventure is provided by a cabin measuring just a few square meters that housed twelve slaves in North Carolina from 1850 onward, along with a Southern Railway Company car just for Blacks. Alongside and around them a poor but symbolic material culture, like the shawl of Harriet Tubman, activist and spy: she helped to free hundreds of oppressed people. The second chapter is dedicated to the freedom struggle and centers on Martin Luther King’s march from Selma to Montgomery, on the student movements, on the Ku Klux Klan and on the Black Panthers, reaching all the way up to more recent history and drawing attention to sociocultural references that are often undervalued. The third chapter focuses on social engagement as a form of resistance and source of hope: in sport, where Afro-American athletes like Wilma Rudolph, Muhammad Ali and “Magic” Johnson have demonstrated their excellence to the world; or in the Vietnam War, when many young men of color were enlisted as privates, and only a few of them came back alive. The name that stands out in the medical field is that of William Montague Cobb, who in the 1940s used science to counter the myth of presumed racial inferiority, while in politics tributes are paid to Obama, to the Black Lives Matter movement and to the militants for the recognition of the rights of Blacks, both men and women. On the fourth floor, the last chapter goes straight to the heart of the influence of Afro-American culture: the spotlight is turned on jazz, hip hop, sitcoms, cinema, visual art and the crafts. From the legendary TV show Soul Train to Michael Jackson, from Kara Walker to Rashid Johnson, leaving out no one, amidst memorabilia, works of art and quotations. In this museum, designed by David Adjaye, you cry and you laugh, you dance and you learn: and it’s all true.

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Smithsonian Institution

Design: David Adjaye

Washington

Foto: Alan Karchmer/NMAAHC.

Foto: Alan Karchmer/NMAAHC.

Foto: Alan Karchmer/NMAAHC.

Foto: Alan Karchmer/NMAAHC.

Foto: Alan Karchmer/NMAAHC.

Foto: Alan Karchmer/NMAAHC.

Foto: Alan Karchmer/NMAAHC.

Foto: Alan Karchmer/NMAAHC.

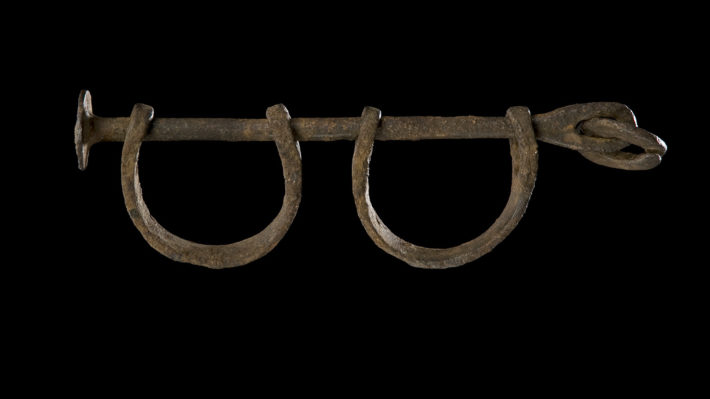

Shackles. Created by Unidentified. Before 1860. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum.

Trumpet owned by Louis Armstrong. September 1946. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Manufactured by Unidentified. Owned by William Montague Cobb M.D. Mid 20th century. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Dr. Michael L. Blakey.

Created by Unidentified. Owned by Harriet Tubman. Silk lace and linen shawl given to Harriet Tubman by

Queen Victoria, ca. 1897. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Charles L. Blockson.

July 4 March through Chapel Hill. July 4, 1964. Created by James H. Wallace. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of James H Wallace Jr, © Jim Wallace.

Photograph by A. P. Mitchell. Subject of Lawrence Leslie McVey.

Subject of 369th Infantry, United States Army. Photographic postcard of Lawrence McVey in uniform 1914 – 1918. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Gina R. McVey, grand daughter.

Black “Sex” jumpsuit owned by James Brown 1970-1989. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Manufactured by Weintraub Brothers Company, Inc. Manufactured by Martin Manufacturing Company. Worn by General Colin L. Powell. Subject of: United States Army. US Army green service uniform worn by Colin L. Powell, 1989-1993. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of General Colin L. Powell, USA (Ret).