6 November 2013

In Eudoxia, which spreads both upward and down, with winding alleys, steps, dead ends, hovels, a carpet is preserved in which you can observe the city’s true form. At first sight nothing seems to resemble Eudoxia less than the design of that carpet, laid out in symmetrical motives whose patterns are repeated along straight and circular lines, interwoven with brilliantly colored spires, in a repetition that can be followed throughout the whole woof. But if you pause and examine it carefully, you become convinced that each place in the carpet corresponds to a place in the city and all the things contained in the city are included in the design, arranged according to their true relationship, which escapes your eye distracted by the bustle, the throngs, the shoving.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (chapter 6: Cities and the sky, 1)

Let’s try imagining Venice as Eudoxia, a city whose structure is contained in the design of an oriental carpet. Its roads make up the woof, while the warp is defined by the network of its canals. The knots of its crimson-colored threads are palaces, houses and theaters; the churches and synagogues, on the other hand, are woven out of cobalt-colored yarn. A broken thread gives rise to a blind alley, flaws in the weave indicate a damaged house or a disused road. The carpet contains the city—it keeps its soul and its secrets.

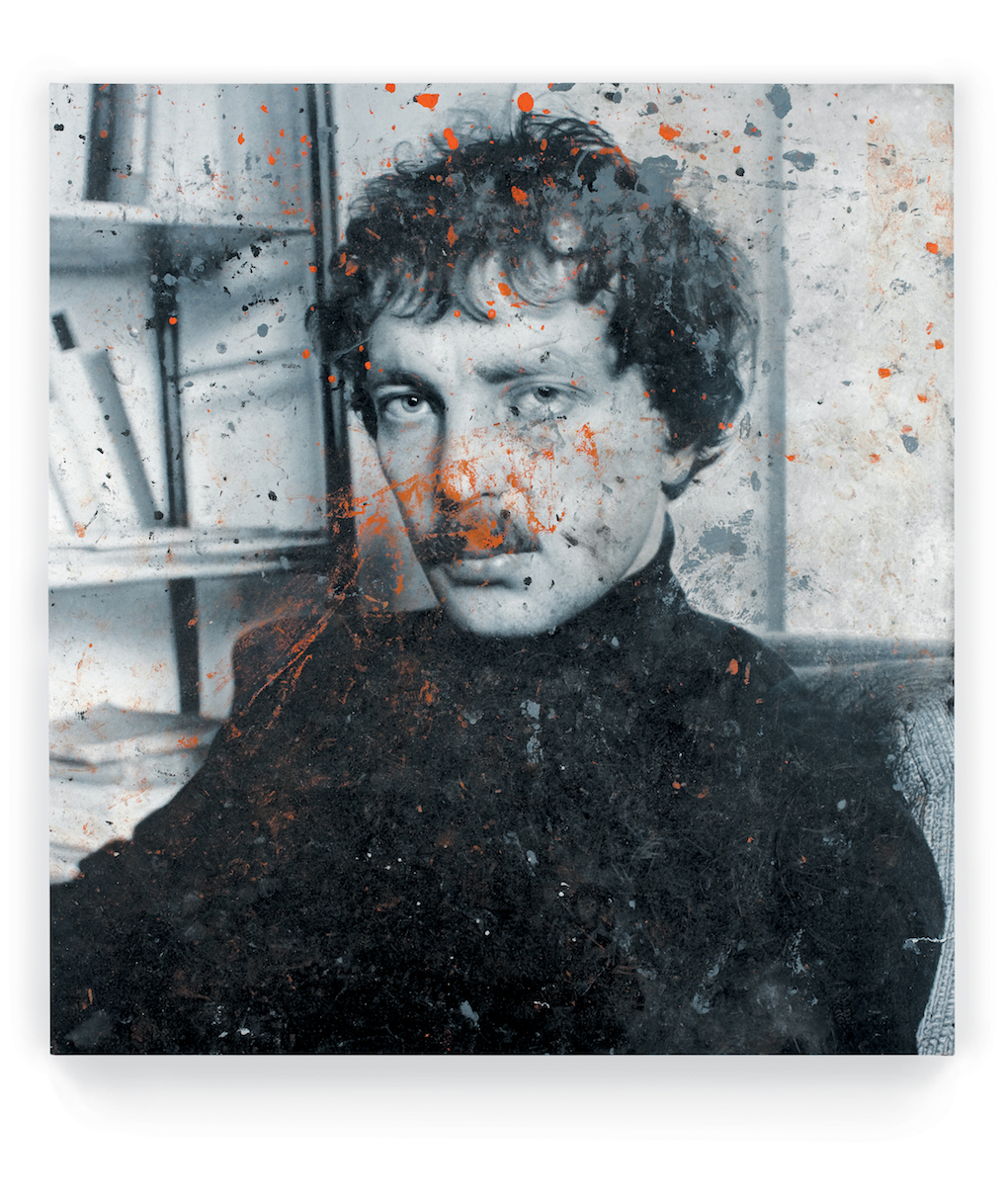

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled (St. John the Baptist), 2009. Photo: Stefan Altenburger.

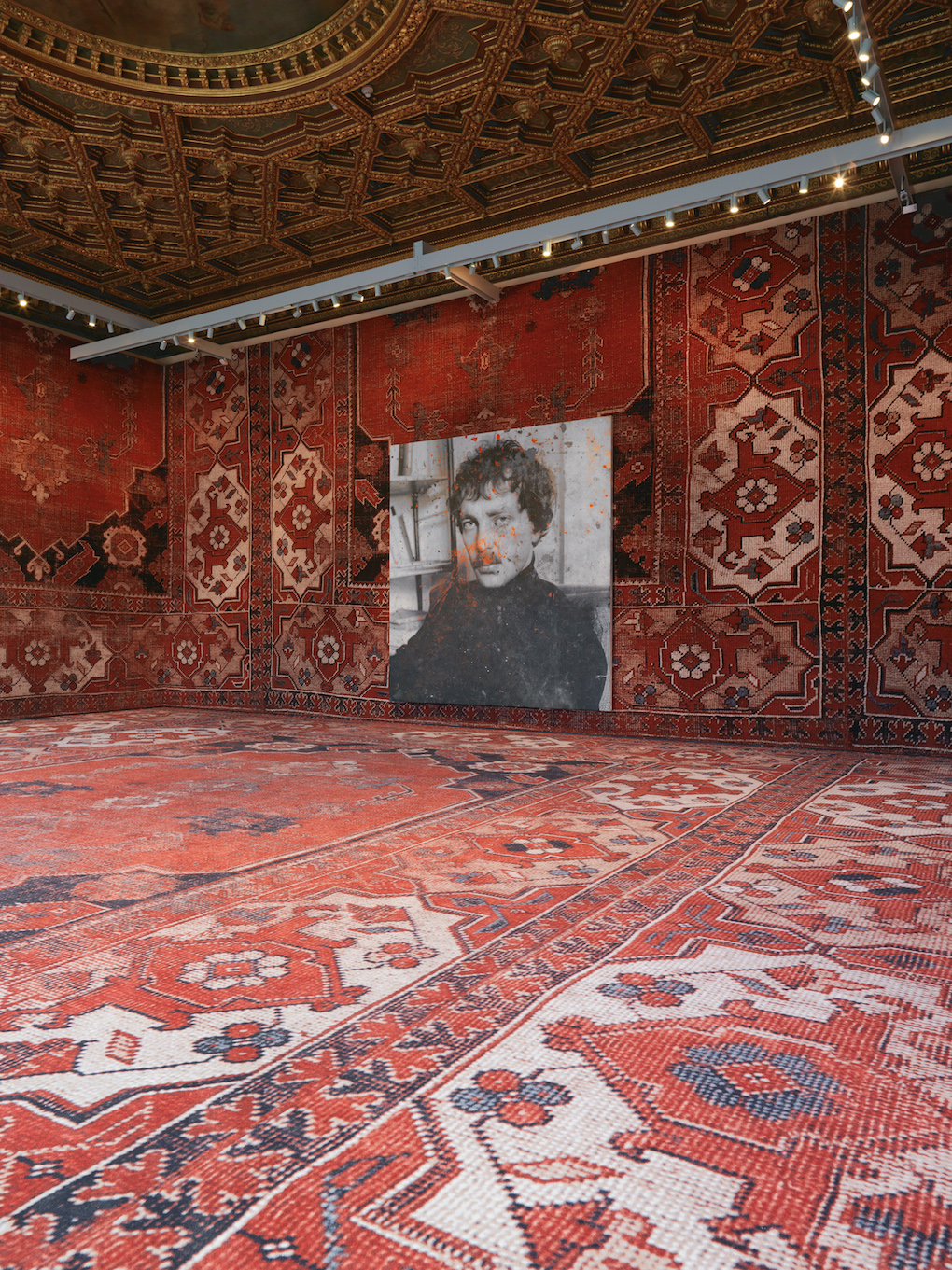

Now, let us imagine that the carpet expands infinitely, that the geometric patterns are multiplied until they cover an entire building—and not just the floor, but also its walls, corners and most inaccessible recesses. As if it were a second skin that reproduces, in the knots of its weave, the topography of the city of Venice. For that is how we can picture the spectacular installation of Rudolf Stingel at Palazzo Grassi: as an imaginary map of the lagoon city, laid out on the surface of a Persian carpet in tones of crimson and magenta.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 2008. Photo: Stefan Altenburger.

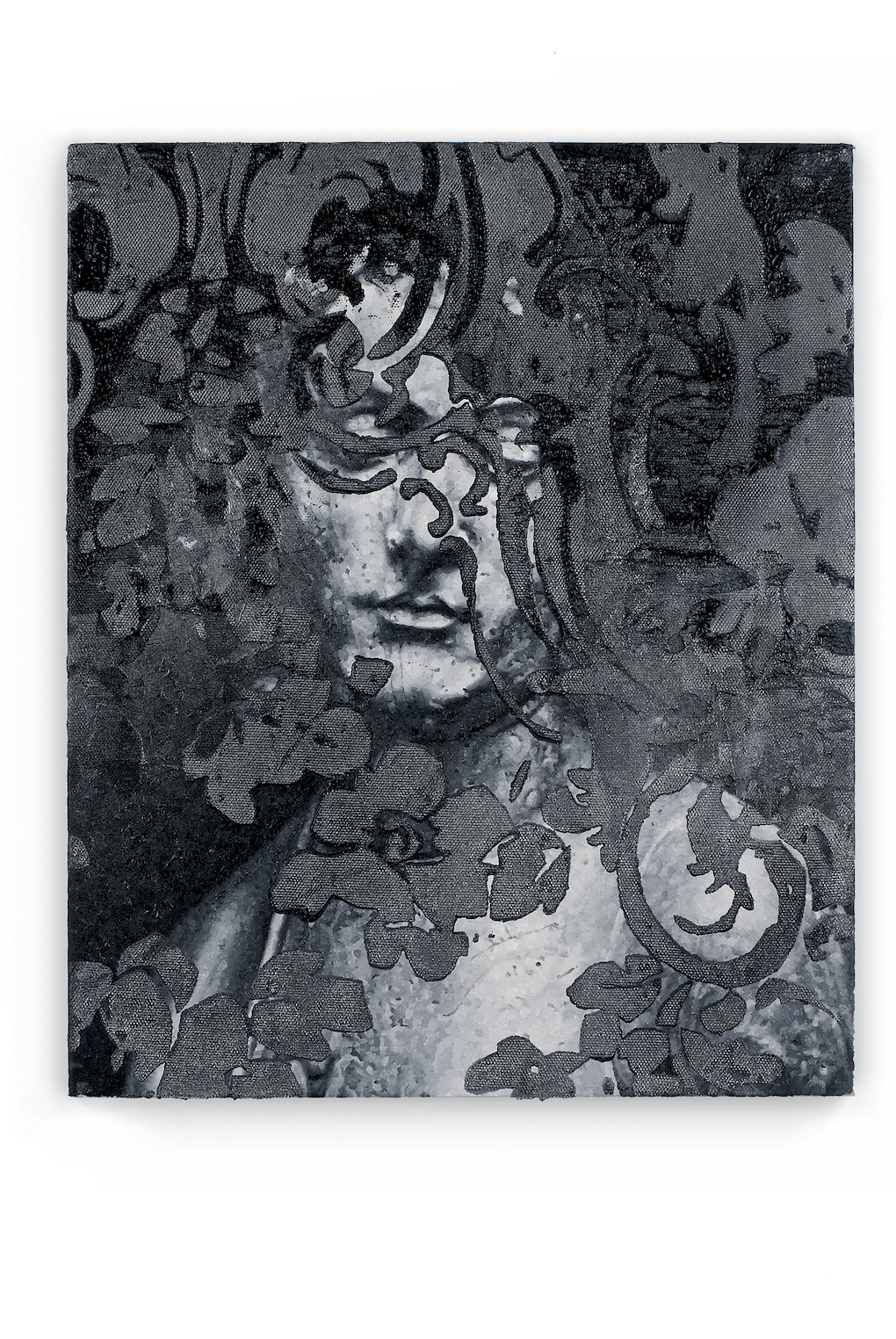

In the rooms on the second floor are hung some abstract paintings by the artist from Alto Adige. They are large silvery canvases, or rather iridescent pseudo-monochromes that, on closer examination, reveal hints of patterns and motifs. The dark swirls on the painted surfaces depict the skies swollen with rain over the lagoon, and the shades of gray paint crystallize the reflections of the sea that bathes Venice. Like windows opening onto the city, the canvases dot the whole area of the carpet-map—they emerge from the walls with their geometric motifs like urban views drained of life.

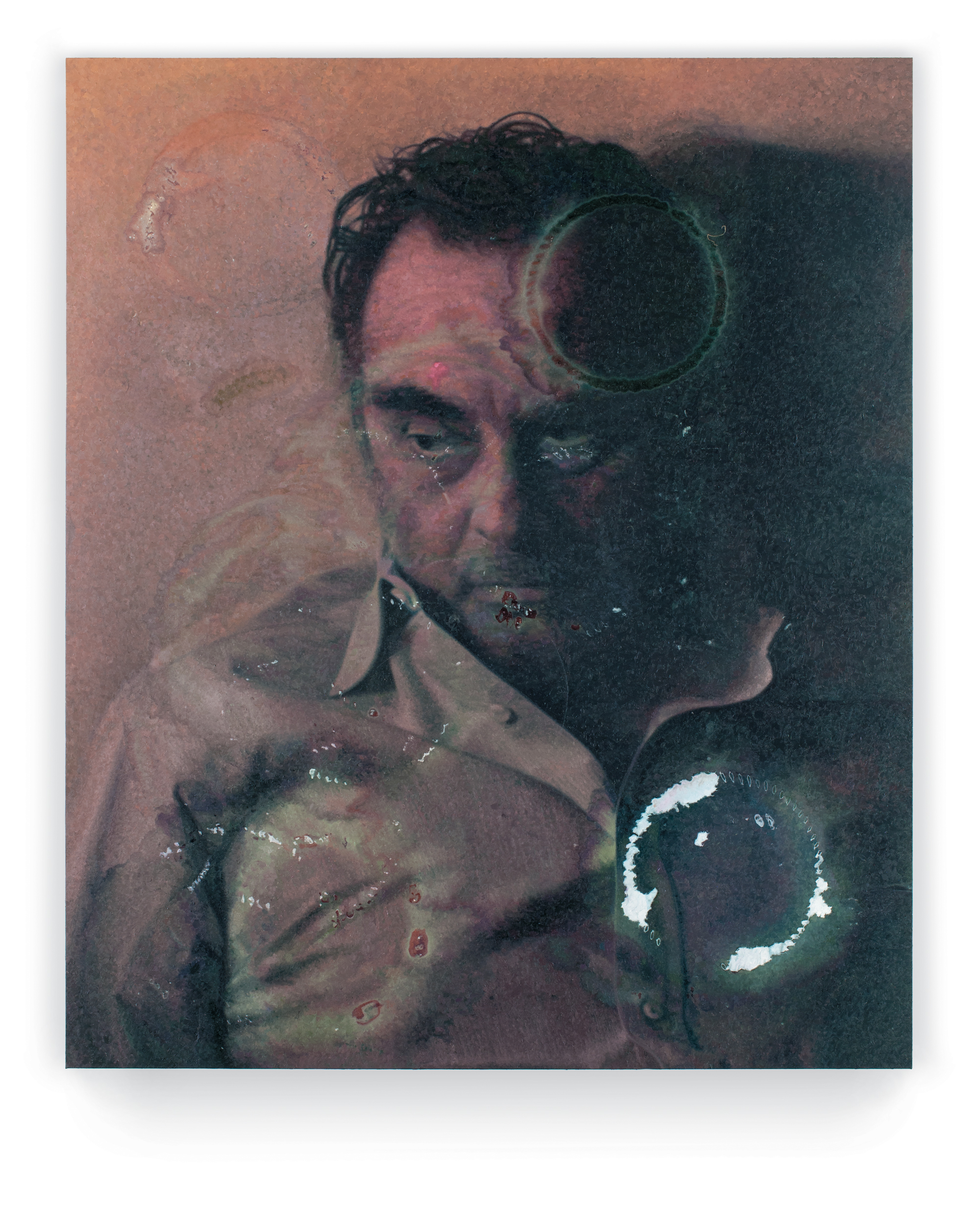

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled (Franz West), 2011. Photo: Stefan Altenburger.

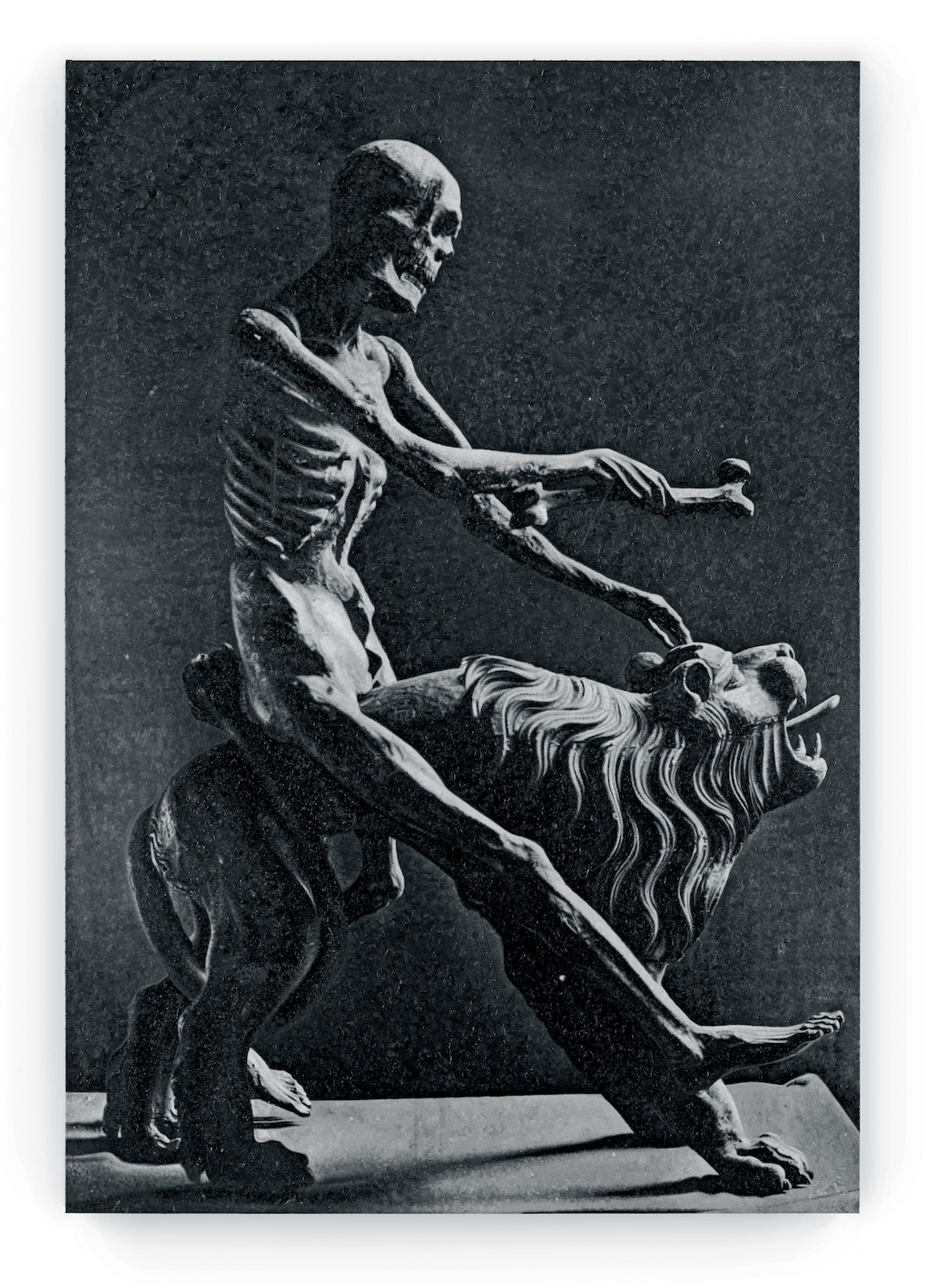

The top floor of Palazzo Grassi houses a second series of pictures in black and white representing ancient wooden statues. At first glance they look like photographs, but in reality they are small photorealistic paintings. The sculptures are of the Madonna and saints, or they are portraits and allegorical images—one painting, the largest of the series, portrays death astride a lion, the symbol of Venice. The atmosphere grows uneasy, the way uncertain—the little sculptures in the pictures surface like suppressed memories (there is an allusion to Freud’s study in Vienna, a room plastered with oriental rugs, covering the floors and walls and draped over the furniture, just as in the Venetian palazzo. Could it be that what Stingel has created here is an original representation of the unconscious?). The painted objects conjure up ancient times, alluding (perhaps) to a flourishing trade in antiques, something for which Venice was once famous—again, the artist is celebrating the myth of an extraordinary, “invisible” city, poised between earth and sea. The city where this diary started and where it ends.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled (St. Barbara), 2009. Photo: Ellen Page Wilson.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 2009. Photo: Andy Keate.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 2009. Photo: Andy Keate.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 1990. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 2012. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 2003. Photo: Alessandro Zambianchi.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled (Franz West), 2011. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 2013. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Follow Federico Florian on Google+, Facebook, Twitter.

By the same author:

ArtSlant Special Edition – Venice Biennale

Notes on ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’. A Venetian tour through the Biennale

The national pavilions. An artistic dérive from the material to the immaterial

The National Pavilions, Part II: Politics vs. Imagination

The Biennale collateral events: a few remarks around the stones of Venice