9 October 2013

In Esmeralda, city of water, a network of canals and a network of streets span and intersect each other. To go from one place to another you have always the choice between land and boat: and since the shortest distance between two points in Esmeralda is not a straight line but a zigzag that ramifies in tortuous optional routes, the ways that open to each passerby are never two, but many, and they increase further for those who alternate a stretch by boat with one on dry land.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (chapter 6: Trading cities, 5)

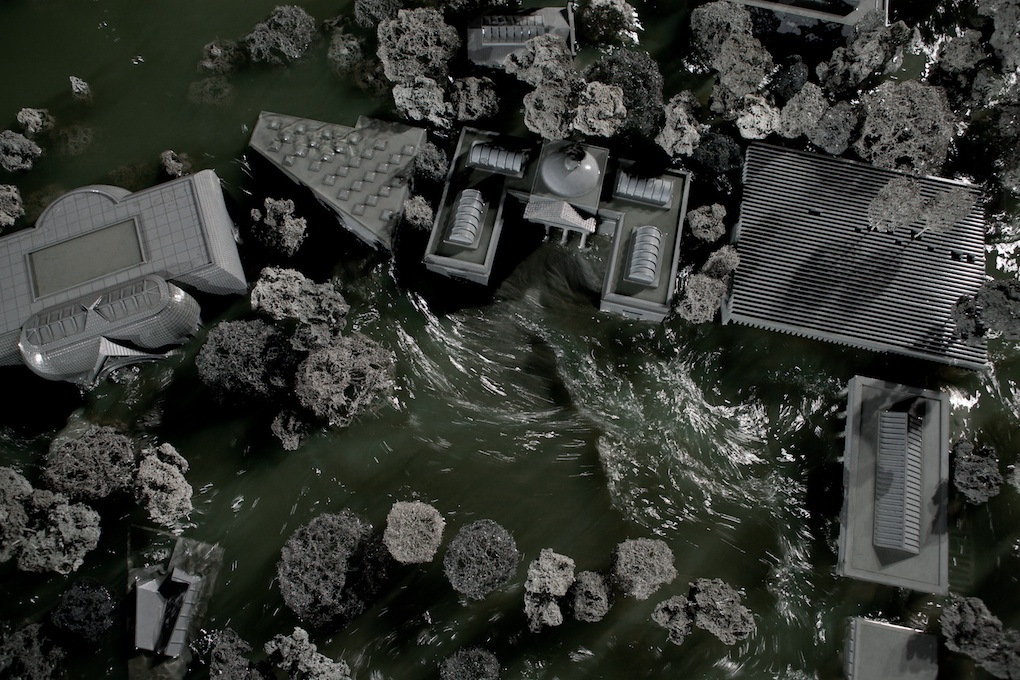

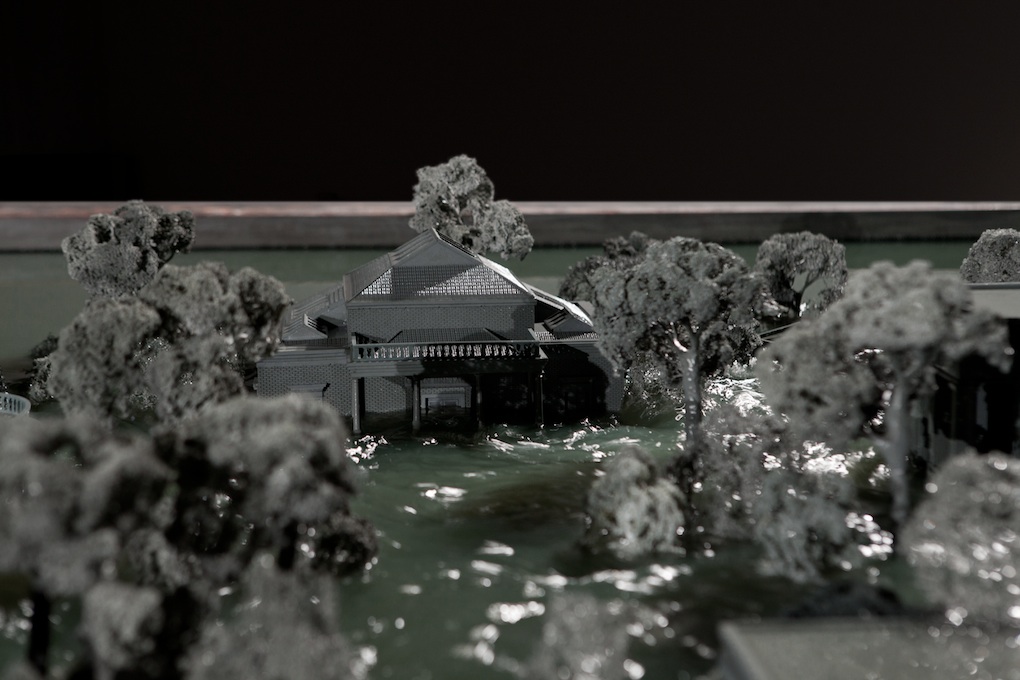

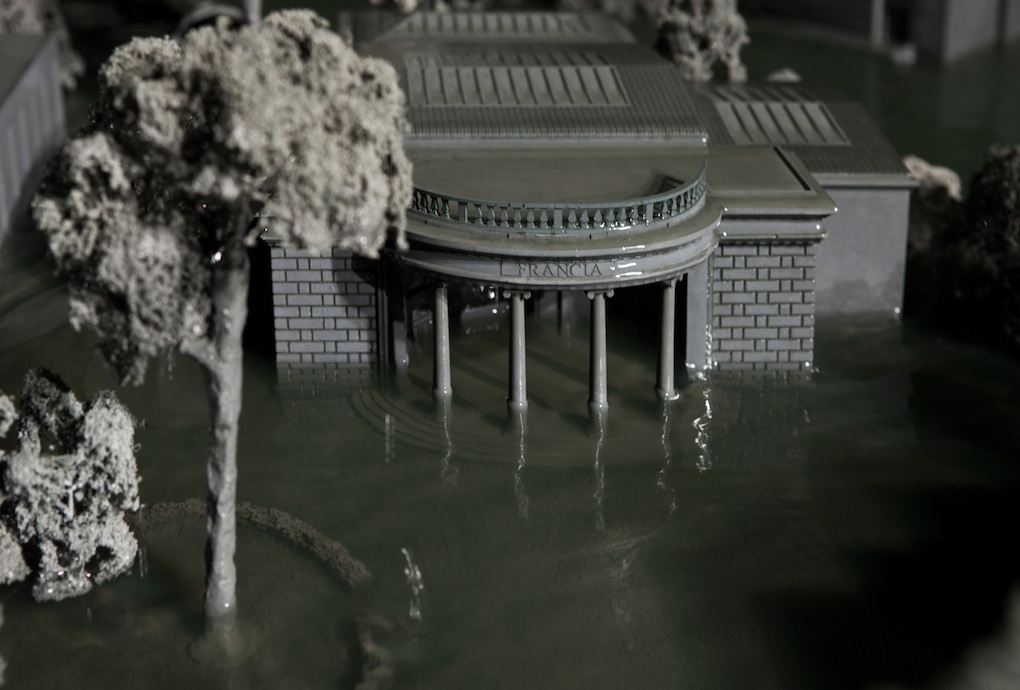

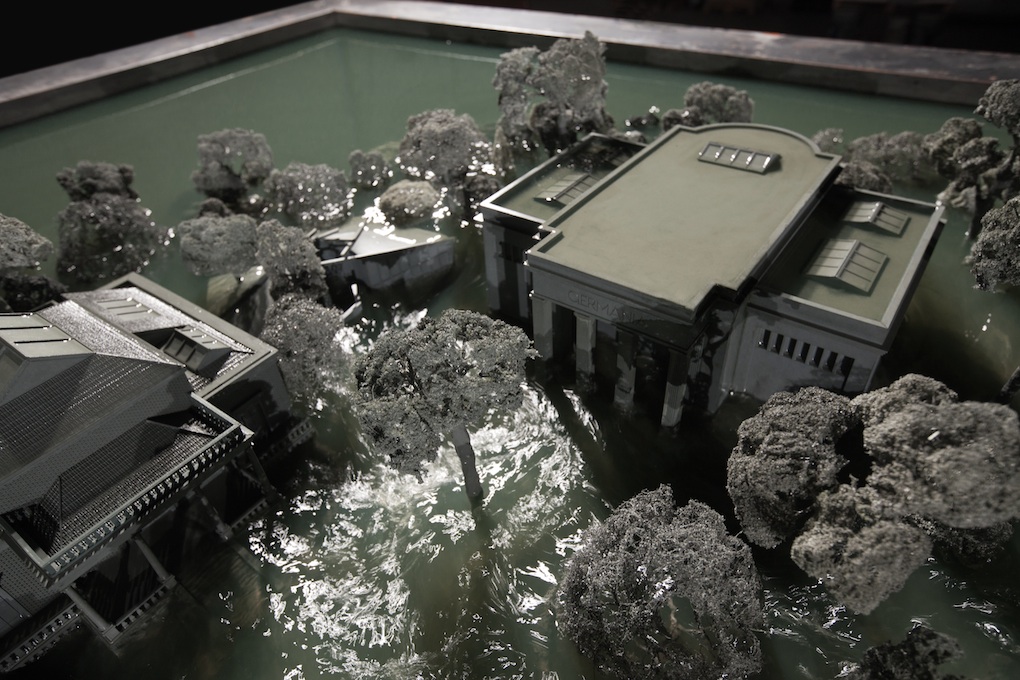

In The Stones of Venice John Ruskin describes the lagoon city as “a ghost upon the sands of the sea, so weak—so quiet—so bereft of all but her loveliness”: Venice is an impalpable, evanescent city, such “that we might well doubt, as we watched her faint reflection in the mirage of the lagoon, which was the City, and which the Shadow.” In conceiving his work for the Chilean Pavilion, Alfredo Jaar seems to have been inspired by this classic of historical and artistic literature. The pavilion at the Arsenale is a large, dark and bare room, in which tones of black and ash gray predominate. At the center of the room stands a platform, to which access is provided by steps—a vague allusion to the bridges of Venice. An enormous tank occupies the entire raised structure: it is filled with black water and its surface is flat. Slowly, something emerges from the depths: the tops of some trees and the roofs and domes of miniature buildings can be made out. A new Atlantis rises from the waters, but its profile is familiar. On close examination, it turns out to be a perfect scale model of the Biennale Giardini, with their national pavilions, their vegetation, their hierarchical and obsolete architecture. The Giardini are gray, like the stones of Venice, like the bridges, streets and churches that dot its surface.

Alfredo Jaar, Venezia, Venice, 2013. Photo: Agostino Osio.

There is only time for a quick glance before the model of the Giardini is swallowed up again—it slowly vanishes, only to rise again after a few minutes. Venezia, Venezia emerges from the water like a ghost or a fleeting vision, materializing an apocalyptic scenario, in which the city, together with the Giardini of the Biennale, is completely submerged by the sea. The artist’s intervention invites us to reflect on the model of the Biennale: he floods and buries it in order to renew it. The installation raises doubts about the legitimacy of a rigid system, a legacy of colonialism, in which just twenty-eight nations have a pavilion of their own (Africa, for example, is completely absent from the map of the Giardini). Jaar is inviting us to reimagine the world in terms of a “geography of self-awareness,” as Pessoa put it, a true realization of the political and economic imbalances between nations.

Alfredo Jaar, Venezia, Venice, 2013. Photo: Agostino Osio.

In Jaar’s view, destruction is the key to any rebirth. This becomes apparent when we see the photograph that introduces the visitor to the pavilion: a picture of Lucio Fontana picking his way through the rubble of his studio in Milan, demolished by bombs in the Second World War. This dramatic event contributed to a maturation and a renewal of Fontana’s practice, resulting in a shift to the poetics of spatialism. Again of destruction—aimed at stimulating a profound “self-awareness”—speaks an intervention realized by the Chilean artist at Skoghall: here, in the center of the Swedish town, he had a museum built out of paper and then set it on fire, with the aim of making the community aware of art. Because, for Alfredo Jaar, this is precisely the artist’s function: “creating models for thinking about [and renewing] the world.”

Alfredo Jaar, Venezia, Venice, 2013. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Alfredo Jaar, Venezia, Venice, 2013. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Alfredo Jaar, Venezia, Venice, 2013. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Alfredo Jaar, Venezia, Venice, 2013. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Alfredo Jaar, Venezia, Venice, 2013. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Alfredo Jaar, Venezia, Venice, 2013. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Alfredo Jaar, Venezia, Venice, 2013. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Lucio Fontana, Milan, 1946.

Follow Federico Florian on Google+, Facebook, Twitter.

By the same author:

ArtSlant Special Edition – Venice Biennale

Notes on ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’. A Venetian tour through the Biennale

The national pavilions. An artistic dérive from the material to the immaterial

The National Pavilions, Part II: Politics vs. Imagination

The Biennale collateral events: a few remarks around the stones of Venice