10 July 2013

Recurrent invasions racked the city of Theodora in the centuries of its history; no sooner was one enemy routed than another gained strength and threatened the survival of the inhabitants. When the sky was cleared of condors, they had to face the propagation of serpents; the spiders’ extermination allowed the flies to multiply into a black swarm; the victory over the termites left the city at the mercy of the woodworms. One by one the species incompatible to the city had to succumb and were extinguished. By dint of ripping away scales and carapaces, tearing off elytra and feathers, the people gave Theodora the exclusive image of human city that still distinguishes it.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (chapter IX: Hidden cities, 4)

As I approach the Lebanese Pavilion, I think of three stories, each of them different, but closely interwoven…

In June 1982 Lebanon was invaded by Israel. In Saïda, this story is still told today: an Israeli pilot, during the days of the attack, refused to strike one of the city’s public schools, jettisoning his bombs in the sea. A few days later, however, the building was hit by another enemy aircraft. The school was partially destroyed.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, author of The Little Prince, was an aviator by profession. During the Second World War, in 1944, his plane was shot down by a German fighter over the sea off the coast of Marseille. For years, the writer’s death remained shrouded in mystery; the wreckage of his aircraft was recovered only about ten years ago.

A pilot, who has crashed with his airplane in the Sahara Desert, meets a child who has fallen to Earth from a distant planet, the asteroid B-612. It is a planet so small that it risks being suffocated by baobabs. A sheep is needed to eat the bushes, so that they do not grow into huge trees. For this reason, the little prince asks the aviator to draw him a sheep. As if objects and things, once drawn, could become real.

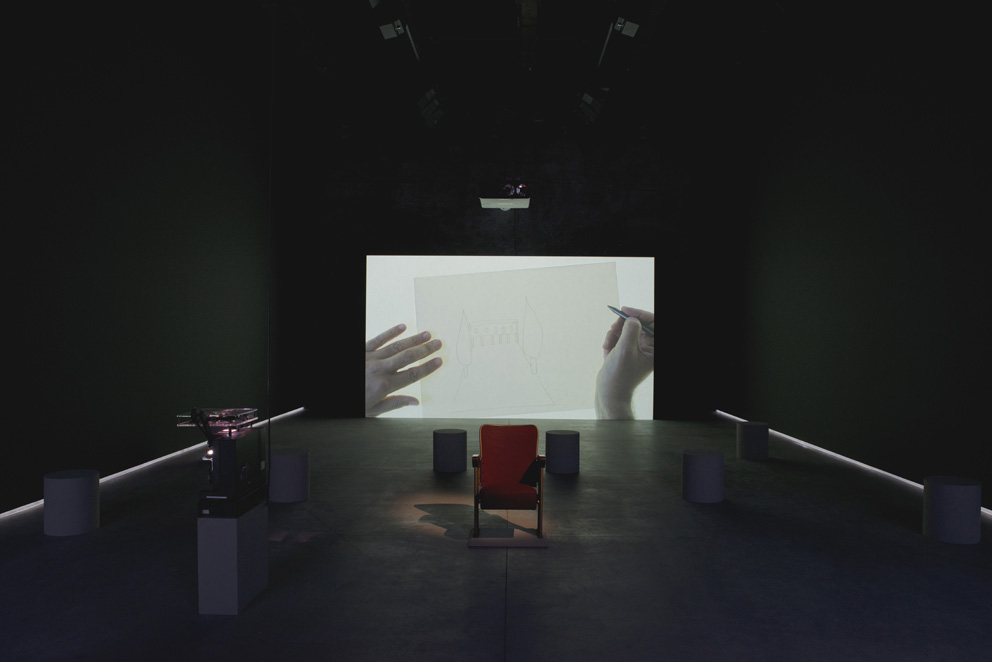

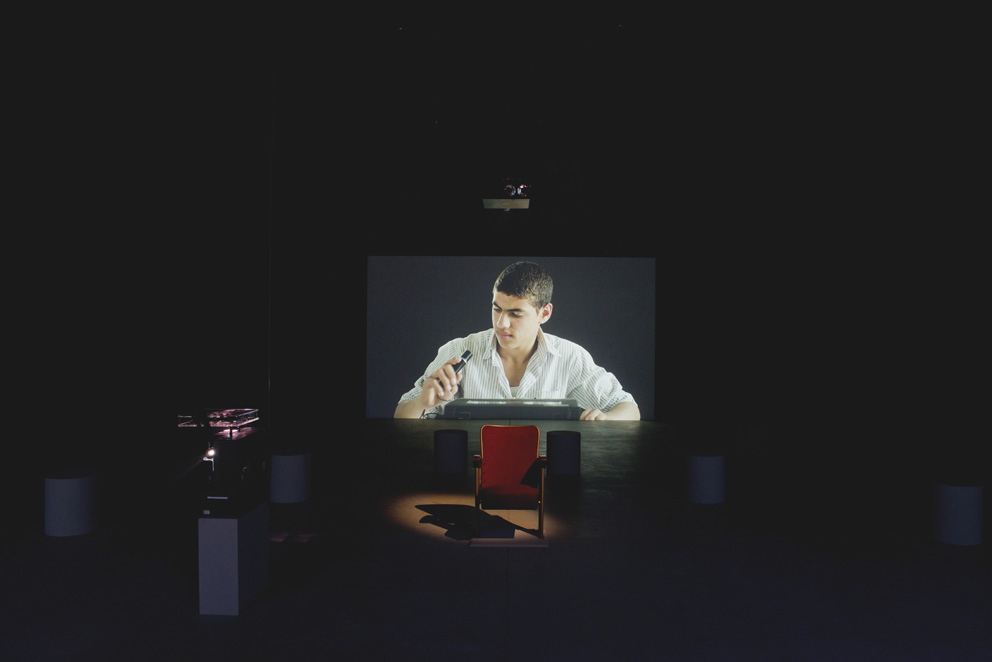

Letter to a Refusing Pilot, the video made by Akram Zaatari for the Lebanese Pavilion, starts in this way: with a take of the first pages of The Little Prince and a drawing of a paper plane, about to take flight. Like the sheep in Saint-Exupéry’s story, the lines drawn in pencil that define the shape of the airplane seem to come alive: the plane becomes real and circles unsteadily over the houses of a deserted, silent Saïda. Only the rippling surface of the sea seems to preserve the memory of the bombing: suddenly, an invisible explosion shatters the expanse of water, the sketches like splinters of dynamite. History and legend merge with the personal biography of the artist, born in Saïda and son of the architect who designed the school bombed in 1982. The adolescent Zaatari is struck by the story of the dissident pilot – a dramatic figure, torn by the conflict between duty and individual morality, just as in one of Aeschylus’s tragedies. Letter to a Refusing Pilot is a homage to an unknown Israeli aviator, a delicate narration that masterfully marries the fluid material of memories with the accuracy of history. The video combines old photos with pages from diaries and archive documents: as I watch the moving pictures, I think of the artist as an archeologist engaged in unearthing the remains of a recent history. The one exhumed by Zaatari, however, is an intimate, familiar past, conjured up through the gaze of a little boy – a gaze similar to that of the little prince, capable of revealing the “essential [that] is invisible to the eye.”

Follow Federico Florian on Google+, Facebook, Twitter.

By the same author:

ArtSlant Special Edition – Venice Biennale

Notes on ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’. A Venetian tour through the Biennale

The national pavilions. An artistic dérive from the material to the immaterial

The National Pavilions, Part II: Politics vs. Imagination

The Biennale collateral events: a few remarks around the stones of Venice