16 December 2014

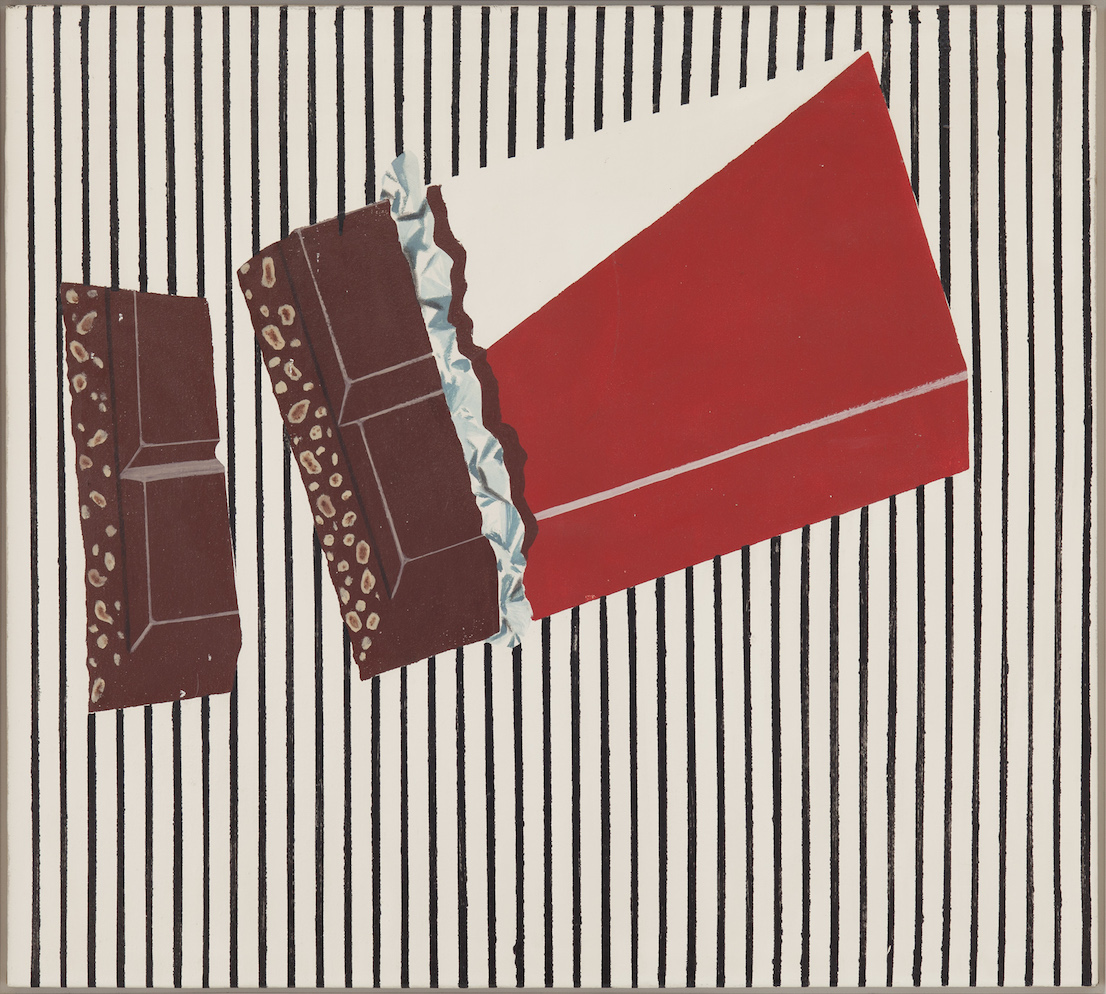

Eclectic and irreverent, armed with an irony that he used to launch fierce attacks on postwar German society. This was the Sigmar Polke presented in all his subversive, aesthetic and political force in a solo exhibition at the Tate Modern in London, organized in collaboration with the MoMA in New York. In order to retrace an artistic output produced over the course of a nomadic life, the exhibition has been laid out in chronological order: it commences with works from the period of “Capitalist Realism,” in which he celebrated the false promises of the consumer society of the early sixties, those insatiable feelings that uprooted the Germans from their tragic Nazi past. His paintings from the time are peopled with sausages, bars of chocolate and girls in bikinis, and are couched in a pop style inspired by advertising and newspapers. This was followed by harsh criticism of abstraction, considered guilty of harking back in an irresponsible fashion to the historical avant-gardes and the utopian ideologies of the early 20th century. Then the dramatic turnaround: in the seventies Polke left Düsseldorf, moving to a commune in the countryside, taking hallucinogenic drugs and starting to travel around the world: from New York to São Paulo to Pakistan. Out of this was born the alchemist who superimposed photographic negatives, toxic pigments and kitsch fabrics of poor quality. “Poison just crept into my pictures,” he said. The social evil of corruption was reflected in the medium, culminating in the Watchtower series of imposing paintings devoted to the control towers of the concentration camps, or perhaps those of the Berlin wall. Polke painted them on sheets of protective plastic resembling bubble wrap and added photosensitive materials to the translucent surface. The paintings darkened, and would continue to darken, smothering memory and obliterating pain.

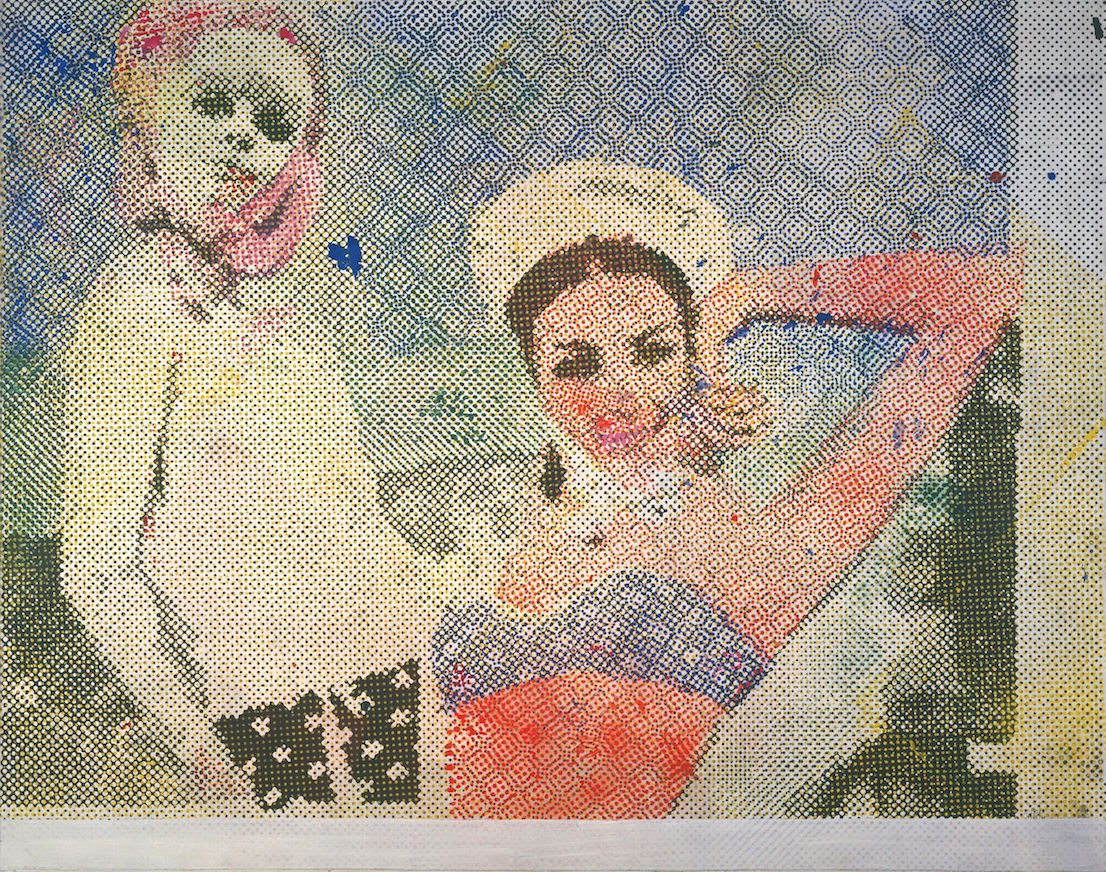

Sigmar Polke, Girlfriends (Freundinnen), 1965/66. © 2014 Estate of Sigmar Polke / ARS, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Sigmar Polke, Chocolate Painting (Schokoladenbild), 1964. © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo: Alex Jamison.

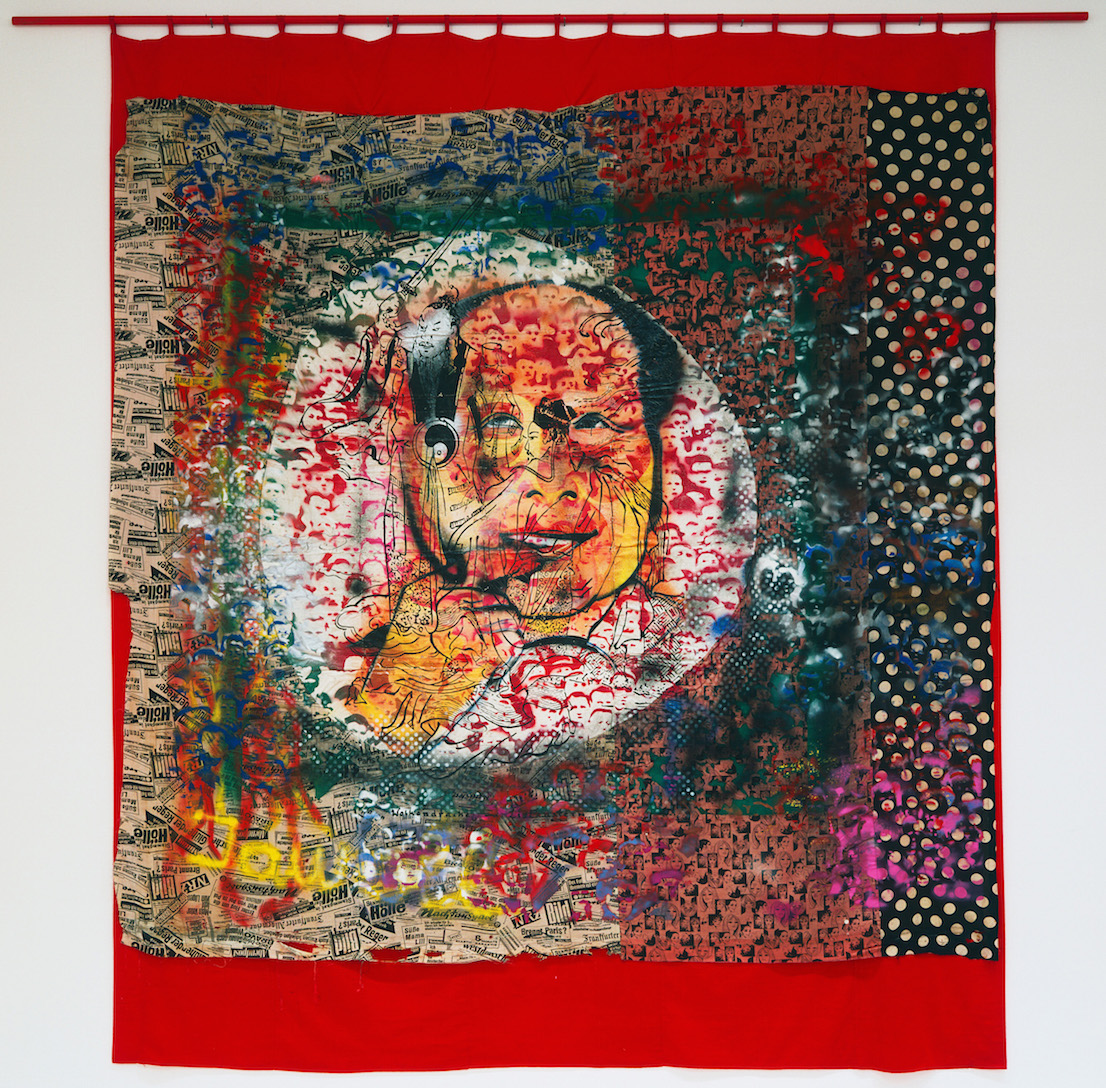

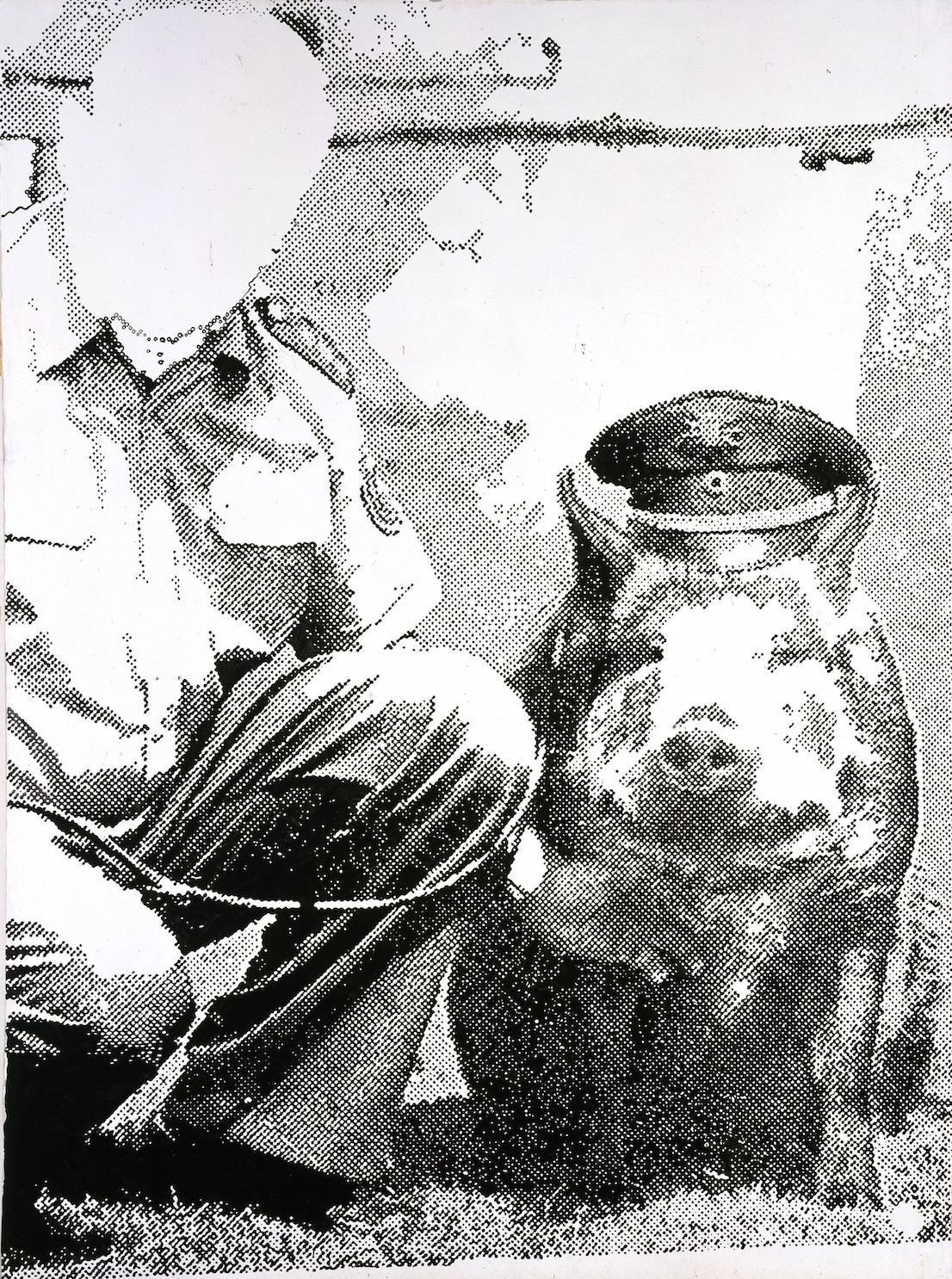

Sigmar Polke, Mao, 1972. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Kay Sage Tanguy Fund

Digital image: © The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: John Wronn. © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

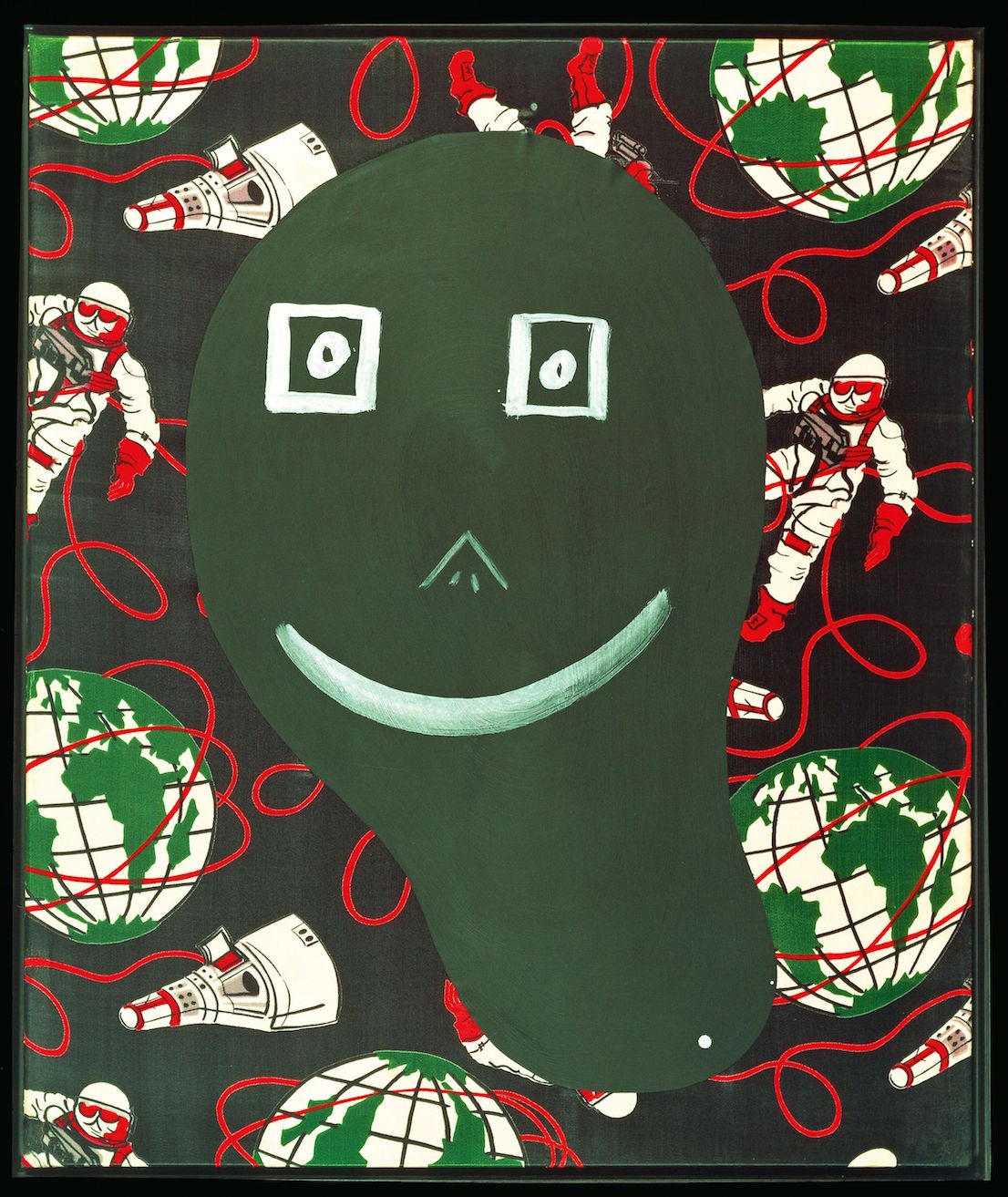

Sigmar Polke, Polke as Astronaut (Polke als Astronaut), 1968. Private Collection. © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

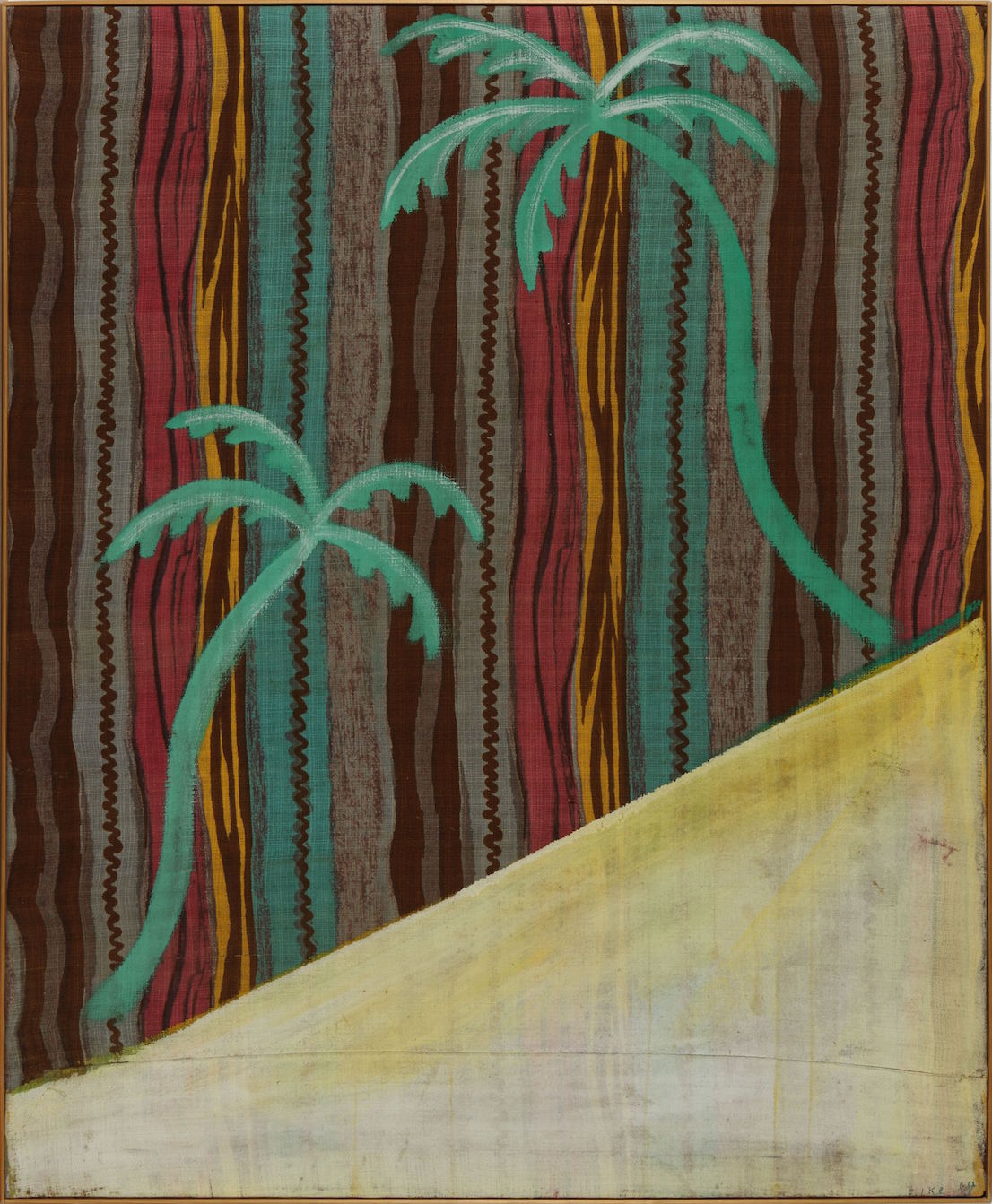

Sigmar Polke, The Palm Painting (Das Palmenbild), 1964. © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Sigmar Polke, Watchtower (Hochsitz), 1984. IVAM, Institut Valencia d’Art Modern, Valencia, Spain. © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

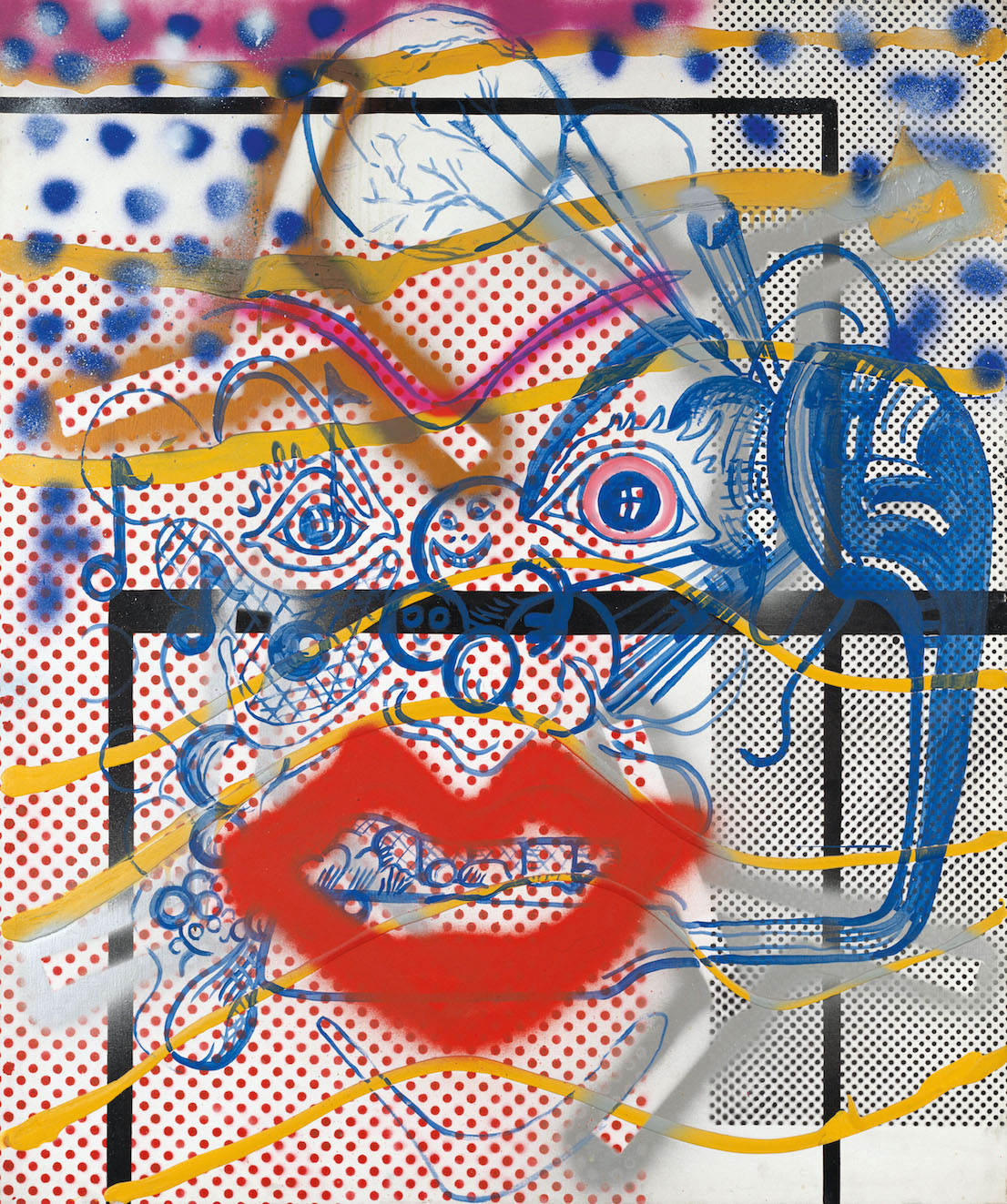

Sigmar Polke, Police Pig (Polizeischwein), 1986. © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Sigmar Polke, Dr Berlin, 1969-74. Private Collection. © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Sigmar Polke, Potato House (Kartoffelhaus), 1967. Courtesy: Vehbi Koç Foundation, Istanbul, on loan to the Neues Museum in Nürnberg. © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo credit: Olivia Hemingway, Tate Photography.

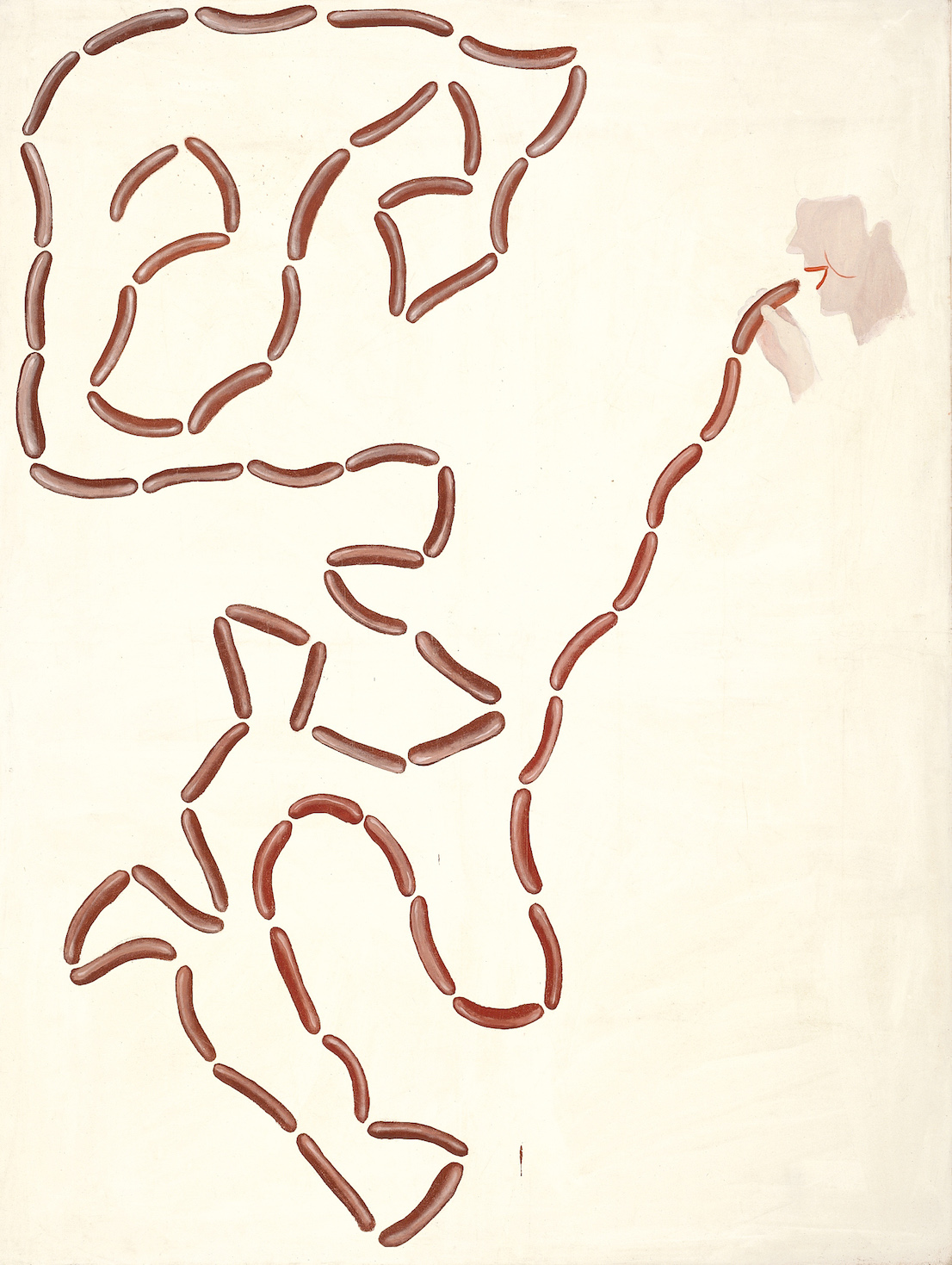

Sigmar Polke, The Sausage Eater (Der Wurstesser), 1963. Flick Collection (Zurich, Switzerland). © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

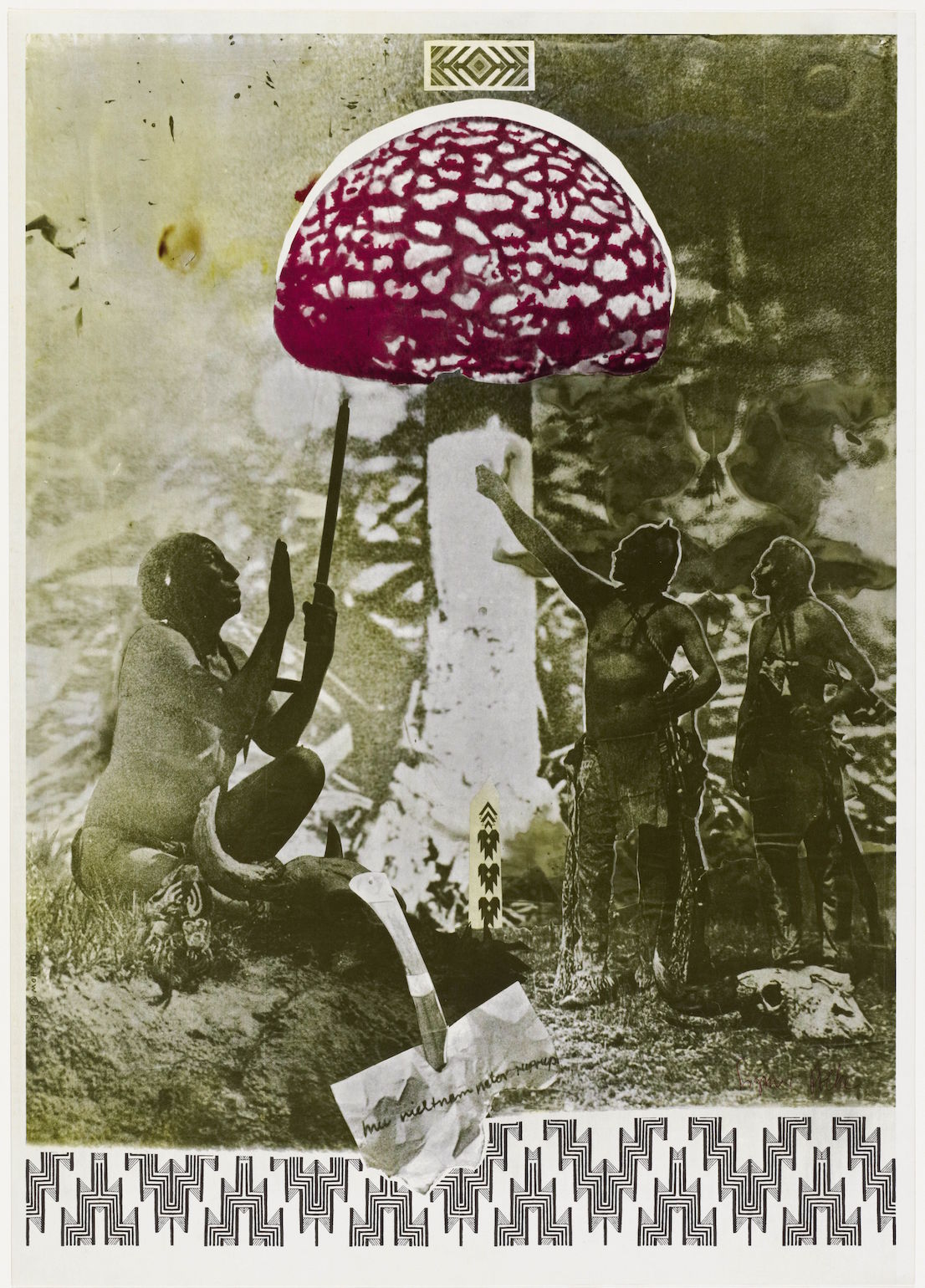

Sigmar Polke, Mu nieltnam netorruprup, 1975. Museum of Modern Art (New York, USA) . © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.