30 January 2015

What do Albert Einstein, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Dean Martin, Elvis Presley, Halle Barry and Liz Taylor have in common, apart from the very important position they hold in the collective imagination of the last hundred years? An exclusive locality that has long been an obligatory destination for the most popular personalities in America, and that after a period of eclipse is now back on the radar of glossy magazines and Hollywood stars. We are talking about Palm Springs, a small city 107 miles from Los Angeles, surrounded by desert and set in the Coachella Valley that is known to today’s Millennials chiefly for the festival of the same name where Pharrell Williams likes to perform. The fondness shown by the cream of Hollywood for the Californian desert is due chiefly to the legendary “Two-Hour Rule,” which held that even on vacation actors under contract with the studios had to make themselves available for film or photo shoots within the aforesaid time limit. In the early twenties, when the exodus of stars began, Hollywood was already too ostentatious, crowded and chaotic. So Rodolfo Valentino, William Powell, Shirley Temple, Harold Lloyd and many other celebrities of the movie world decided to winter in the desert of the Coachella Valley, where in 1938 Palm Springs, already a chic resort, was officially recognized as a municipal corporation.

Palm Springs, a bird’s-eye view.

Over the previous two millennia, Palm Springs had been just a stretch of desert alleviated by lush palm groves and the now famous hot springs. It is to these, obviously, that the Californian city owes its present name, as well as the one given it by its first inhabitants, the Agua Caliente band of Cahuilla Indians, who called the place “Se-Khi”, or “Boiling Water.” In 1853 the mineral sources of Palm Springs appeared for the first time on a map published by the American government. Twenty years later President Rutherford Hayes gave the Southern Pacific Railroad a mandate to build a line all the way to the Pacific Ocean, obliging the natives to give up much of their lands. In 1884 Palm Springs had its first non-Indian inhabitant, a certain Judge John Guthrie McCallum who moved there from San Francisco in the hope that the place’s climate and hot springs would cure his son of tuberculosis. The date of birth of the local tourist industry can be traced back instead to 1886, with the opening of the Palm Springs Hotel.

Over the following decades Palm Springs grew with great speed, in part thanks to mythical hotels like the iconic Desert Inn run by Nellie Coffman, or “Mother Coffman” as she was known, which played a fundamental role in attracting the first tourists among the travelers making their way along the dusty roads in the direction of Los Angeles. The pilgrimage of Hollywood stars reached its peak in the fifties, when Frank Sinatra and his legendary Rat Pack—Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Joey Bishop and Peter Lawford—became a fixed presence in the Californian palm groves. But, as is well known, celebrities like to flock together, which is why names of the caliber of Lauren Bacall, Kim Novak and even President Dwight Eisenhower were soon added to the list.

Twin Palms, Sinatra House, Palm Springs, California, designed by E. Stewart Williams in 1947. Courtesy: Beau Monde Villas.

Many tales are told of the crooner famous for his rendering of My Way and his house, Twin Palms, which is still there to bear witness to the glories of Old Blue Eyes’ golden years. For example, that a crack in one of the bathroom sinks, which can still be seen, was caused by a bottle of champagne that Sinatra threw at his wife of the time, the actress Ava Gardner. Or that when it was time to serve cocktails by the swimming pool (a pool in the shape of a piano, which has not moved an inch since the fifties either), a Jack Daniel’s flag was hoisted proudly over Twin Palms to alert the neighbors—the movie star Cary Grant and the comic Jack Benny.

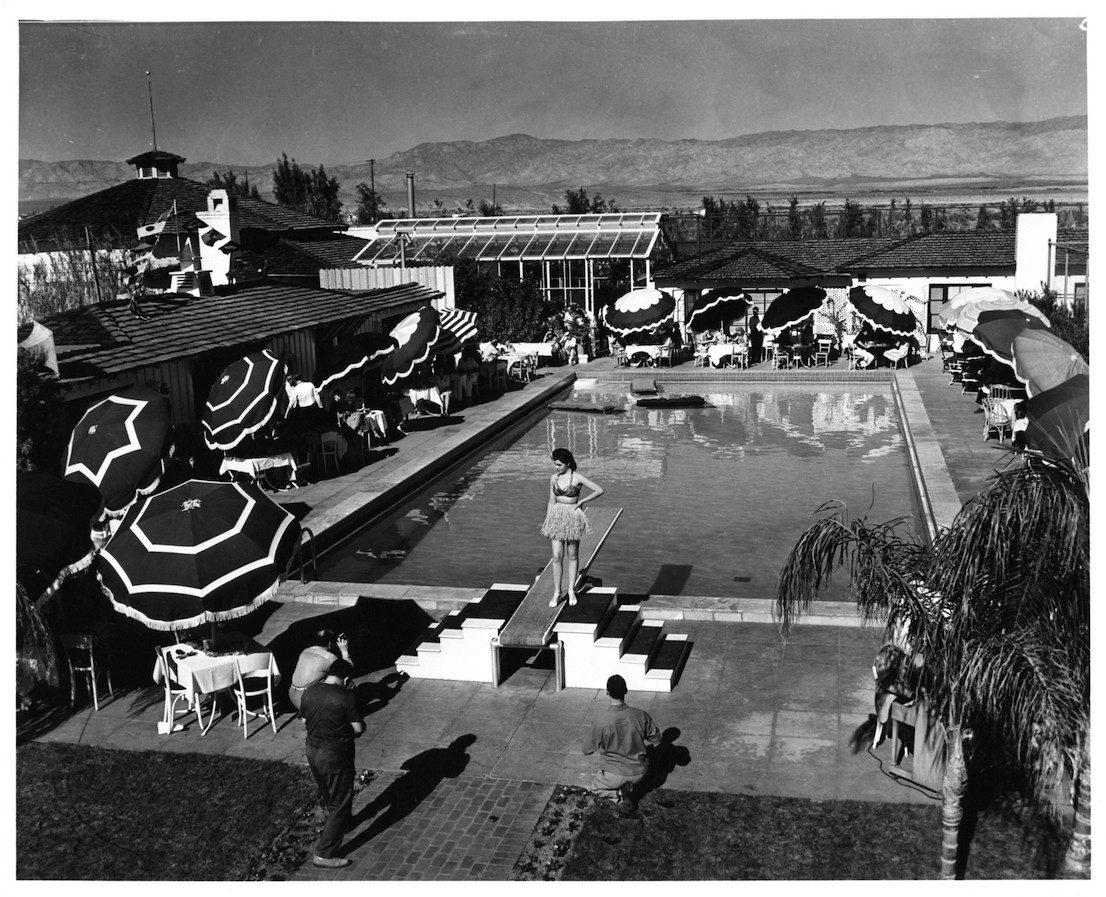

Another mythical place in the Palm Springs of those years was undoubtedly the Racquet Club. Sixty years before Pharrell arrived in the oasis to play the Coachella Festival, it was the similarly named Charles Farrell, an icon of silent film in the twenties, who founded the club with the actor Ralph Bellamy, after the pair had been expelled from the tennis courts of another hotel. “There aren’t many places that are more Palm Springs than the Racquet Club,” as Nicolette Wenzell, associate curator of the Palm Springs Historical Society, put it eloquently when a fire unfortunately destroyed much of the complex last summer. It was here that the famous jazz clarinetist Artie Shaw came on his honeymoon with Lana Turner, in the third of his eight marriages. Here, between one tennis match and another, Clark Gable and the star of West Side Story Natalie Wood spent their afternoons. Here, the story goes, a twenty-two-year-old blonde called Marilyn was approached and signed on by an agent of the William Morris agency while sunbathing by the pool.

Racquet Club, New Year’s Eve Party, Palm Springs, California, 1940. Courtesy: Palm Springs Historical Society.

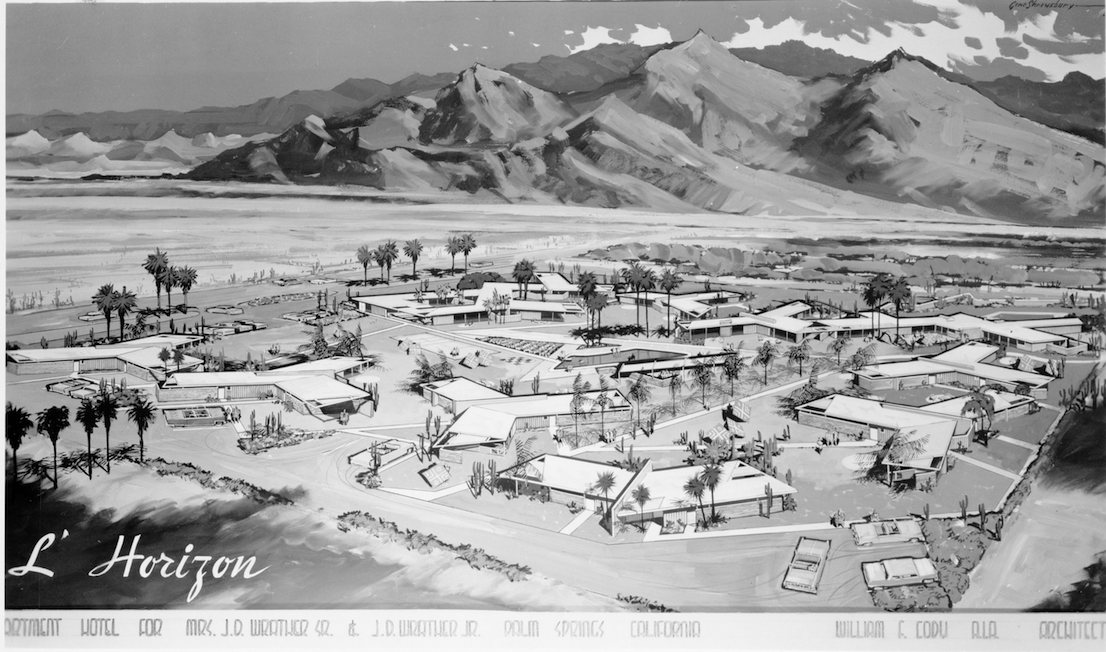

Palm Springs is also celebrated for the architectural style that has accompanied its consecration as a nerve center of American glitterati: the so-called desert modernism that characterized the works of Richard Neutra, John Lautner, Donald Wexler, Albert Frey and the many others who designed hotels, houses and swimming pools in the desert of Riverside county. From the flat roof of Sinatra’s house to the multitude of boutique hotels that sprang up in that period, the common features were the use of glass, the reliance on essential lines and the alternation between open and closed spaces that was intended to convey a sense of simple and informal elegance. Of course, these were the intentions, but simplicity has never been a big thing in Palm Springs. Take for example the hotel The Horizon, famous because it was here that the aforementioned Marilyn created a scandal and in all probability stirred sighs of desire by taking a shower in the open air. The owners were in the habit of organizing three-day parties at which guests were flown on private jets to the Kona Kai Club in San Diego, 125 miles away, with a stopover at Disneyland for supper.

Everyday life in Palm Springs is well captured in a photo taken by Slim Aarons in 1970 that has become rightly famous: Poolside Gossip. In the picture a couple of women with elegant hairstyles and wearing fashionable clothes are seated on sunbeds by the swimming pool of the house owned by the businessman Edgar Kaufmann, designed by Richard Neutra (and recently brought back to its original splendor thanks to the repair and restoration work carried out on behalf of its present proprietor, the tycoon Brent Harris). As an artist, Aarons declared, his aim was to was to photograph “attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places.” And in those years nothing was more attractive than Palm Springs. It is worth quoting from an article commenting on the picture that appeared in Elle last July: “While there are many contemporary women who embody effortless off-duty chic (Gisele, Beyoncé, Kate Moss), there’s something particularly irresistible about the sleek, burnished ladies of Aarons’ era, basking on beaches in hostess gowns and printed pants—perhaps because their allure had little to do with youth or conventional beauty; it was an attitude, an optimism. His photos are like postcards from the good life, in which you can practically hear the clink of ice in highball glasses.”

The Horizon Hotel, Palm Springs, California. Architectural drawing by William F. Cody, circa 1952. From the Wrather Papers (CSLA-23). Courtesy: William H. Hannon Library, Loyola Marymount University.

The community of Palm Springs is understandably proud of this glossy past, and has even named the arteries of the city after the stars of the early days: anyone taking a tour of the place will not be able to avoid going down Frank Sinatra Drive, and then turning onto Bob Hope Drive or carrying on as far as Gerald Ford Drive. And yet the city is no longer just a place haunted by memory, crushed under the weight of a glorious past. In recent years, Palm Springs has begun to flourish again as a destination for élite tourism, luring, in a modern remake of the rush to the desert in the first half of the 20th century, the big names in show business. Its retro-chic settings, its sun-drenched expanses ringed by palms and its fashionable hotels and clubs have begun to draw a new generation of visitors and entrepreneurs. Many come here between January and April, fleeing the harsh winters of the northern United States and Canada to take advantage of the 350 days of sunshine a year of which Palm Springs is happy to boast.

In 2013, for instance, Leonardo DiCaprio declared that he would need time to relax after the bender of The Wolf of Wall Street. No sooner said than done: last March the actor bought a house designed by Donald Wexler in 1963 for Dinah Shore, the most popular female voice of the forties and fifties. The house, located in the area of Old Las Palmas, has six bedrooms and eight bathrooms and, thanks to careful restoration work, retains its original 1950s style.

The return of the old boutique hotels of the Hollywood celebrities onto the scene has not gone unnoticed by companies like Virgin America, which in the summer of 2013 launched a weekly flight from New York. And the revival of Palm Springs has also benefited Modernism Week, an ambitious program of events that for ten years has been celebrating the architectural lines of the city. It is held every February (and, in a scaled-down form, on the Columbus Day weekend, in October) and comprises over a hundred events, ranging from a guided tour of the arcades designed by Neutra, Wexler and William Krisel to lectures, screenings of old movies and themed parties that attempt, and inevitably fail, to emulate the atmosphere of the ones held by Sinatra. From February 12 to 22 next the festival will celebrate its tenth year with cocktail parties and screenings of documentaries and movies, as well as the ritual opening to the public of some of the most fascinating mansions in the Coachella Valley.

Kaufmann House, Palm Springs, California, designed by Richard Neutra in 1946.

Who, for example, wouldn’t like to book a week at the Willows Inn, one of the place’s many hotels that ooze with history? It is certainly another diorama of the scintillating and aspirational life on which Palm Springs has hinged its touristic comeback. Built as a winter retreat by William and Nella Mead, one of the most influential couples in the political and business circles of 1920s Los Angeles, its design was placed in the skilled hands of the Californian “starchitect” William J. Dodd. The Willows was completed in 1925, within spitting distance of the aforementioned Desert Inn and with a view of the entire Coachella Valley. Toward the end of the decade, however, William Mead died from acute pneumonia, and his wife decided to sell the house. The buyer was another celebrity, although in a different sector and of completely different origin. Samuel Untermyer came from New York, and was a genuine star of the legal profession. A staunch supporter of Woodrow Wilson, in 1920 he had been counsel for the Lockwood Committee, which investigated a system of bribery in the unions of the New York building industry, and had then drawn the ire of Rockefeller, Ford and J. P. Morgan with his demands for stock-market regulation. Untermyer liked to invite his friends to his house in Palm Springs. Shirley Temple was one of them: she was once brought to the Willows expressly to meet the governor of New York, Herbert Lehman.

Yet the most timeless icon associated with the Willows was not part of the Hollywood jet set, nor someone who had to adhere to the Two Hour Rule. Albert Einstein was an intimate friend of Untermyers’ (in fact the relationship was so close that Albert and his wife Elsa used to come and stay at the house even in the lawyer’s absence). In reality, the father of the theory of relativity was a vacationer just like the others: he came to Palm Springs to relax and sunbathe (in the nude, according to reports of the time). On the top of the small hill from which the house overlooks the valley there is still the bench on which Einstein used to sit in the evening, gazing at the landscape and probably indulging in happy thoughts of the kind shared by people with a much lower IQ than his. Untermyer died in 1940, leaving the house to his family, who kept it until the middle of the following decade, when it was bought by Marion Davies, comedienne of silent cinema and wife of the publishing magnate William Hearst, who also bought the already legendary Desert Inn. After a long period of semi-abandonment, the Willows is now owned by Tracy Conrad, a physician from Los Angeles who has had it renovated, turning it into the luxury vintage hotel it is today.

Racquet Club, Palm Springs, California, 1939. Courtesy: Palm Springs Historical Society.

The mushroom-shaped house on Southridge Drive that belonged to Bob Hope was designed instead by John Lautner in 1973 and, as the New York Times has written, “it was built to resemble a volcano, with three visorlike arches and an undulating concrete roof, a hole at its center opening a courtyard to the sky.” In February 2013 it ended up on the market for the first time, at an asking price of fifty million dollars. A year later the price had fallen to thirty-four million. In 1986, when Hope was still alive, a reporter from the Los Angeles Times was invited to a fundraising dinner at the villa and described elegant interiors decorated with pictures in the manner of Picasso, trophies (“I want to get enough to fill it,” said the comic, already 83 at the time) and photos of himself in the company of Reagan, Nixon and Bing Crosby.

When all is said and done, the story of Palm Springs is an American one. It is the story of a place not just attached to its cultural roots, but constantly fascinated, challenged and haunted by them. Its origins are almost mythical, its style is one that the whole world venerates and occasionally tries to re-create. But America also teaches us that, while Leonardo DiCaprio is perhaps not quite the same as a crooner with blue eyes and a piano-shaped swimming pool by which Marilyn Monroe sipped a cocktail, there is always room for the pride in the past to become the positive, creative spur of the present. In any case, at the outset, before the Desert Inn and all that followed it, Palm Springs was just an expanse of arid land burnt by the sun for more than three hundred days a year. This didn’t stop it from becoming a legend of American high life. A place where, to quote the sardonic words of G.B. Trudeau, creator of the Doonesbury comic strip, “they think homelessness is caused by bad divorce lawyers.”

Enco Gas Station, Palm Springs, California, designed by Albert Frey in 1965.

Palm Springs City Hall, Palm Springs, California, designed by Albert Frey in 1952.