31 July 2013

In Raissa, life is not happy. People wring their hands as they walk in the streets, curse the crying children, lean on the railings over the river and press their fists to their temples. In the morning you wake from one bad dream and another begins. At the workbenches where, every moment, you hit your finger with a hammer or prick it with a needle, or over the columns of figures all awry in the ledgers of merchants and bankers, or at the rows of empty glasses on the zinc counters of the wineshops, the bent heads at least conceal the general grim gaze. Inside the houses it is worse, and you do not have to enter to learn this: in the summer the windows resound with quarrels and broken dishes.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (chapter IX: Hidden cities, 2)

“[…] and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”. With these words Thomas Hobbes, in his Leviathan, described the state of nature, the primitive condition of humanity, in which there is no government nor any laws, in which total anarchy reigns and there is a situation of perpetual war. A “natural” condition in which man reveals his deepest essence, that of a predatory wolf, the enemy of his fellows. Homo homini lupus est, as Plautus wrote in one of his celebrated comedies.

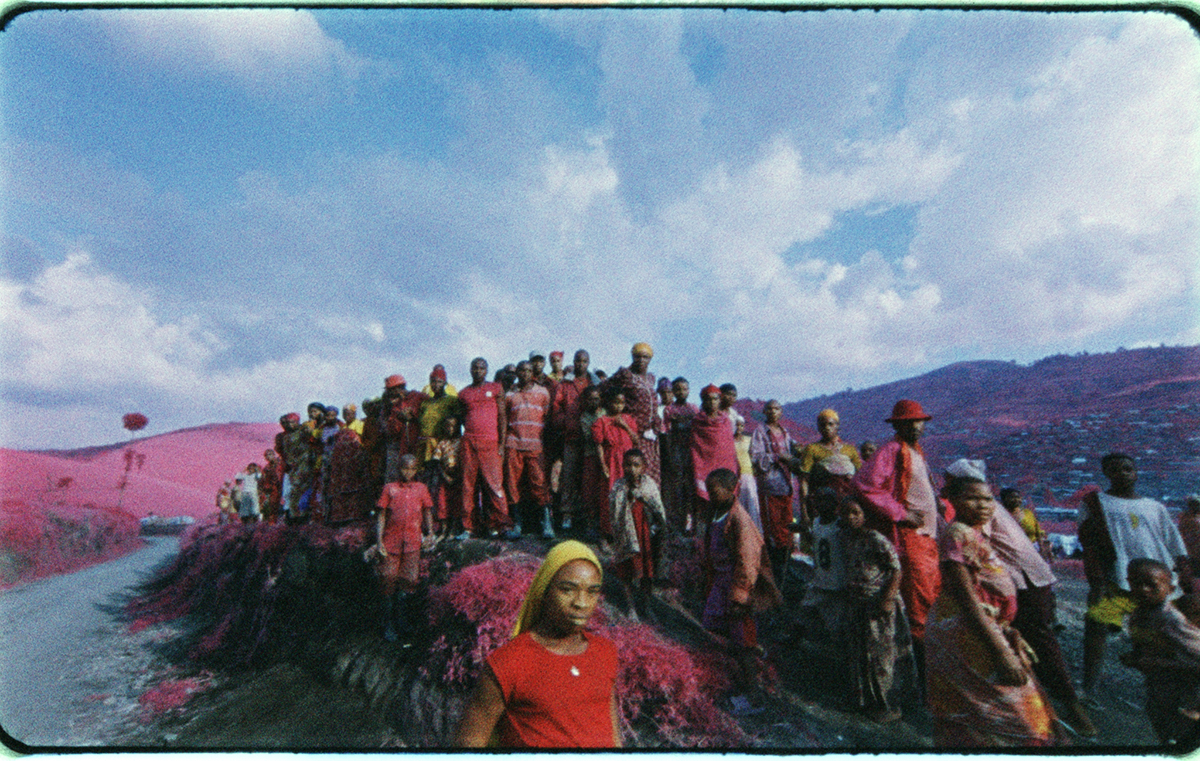

Richard Mosse, Beaucoups Of Blues, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2012.

The Enclave, the video installation created by Richard Mosse for the Irish Pavilion appears to represent this mythical and primordial state of nature. We are in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, an ungovernable territory afflicted by a civil war of which little is known and little is said—an “enclave” of rebel power, a portion of land outside the sphere of government control. Here corruption, violence and death prevail—the landscape is tinged with red, the color of blood, and cobalt blue, the color of resignation.

Richard Mosse, The Enclave, 2013.

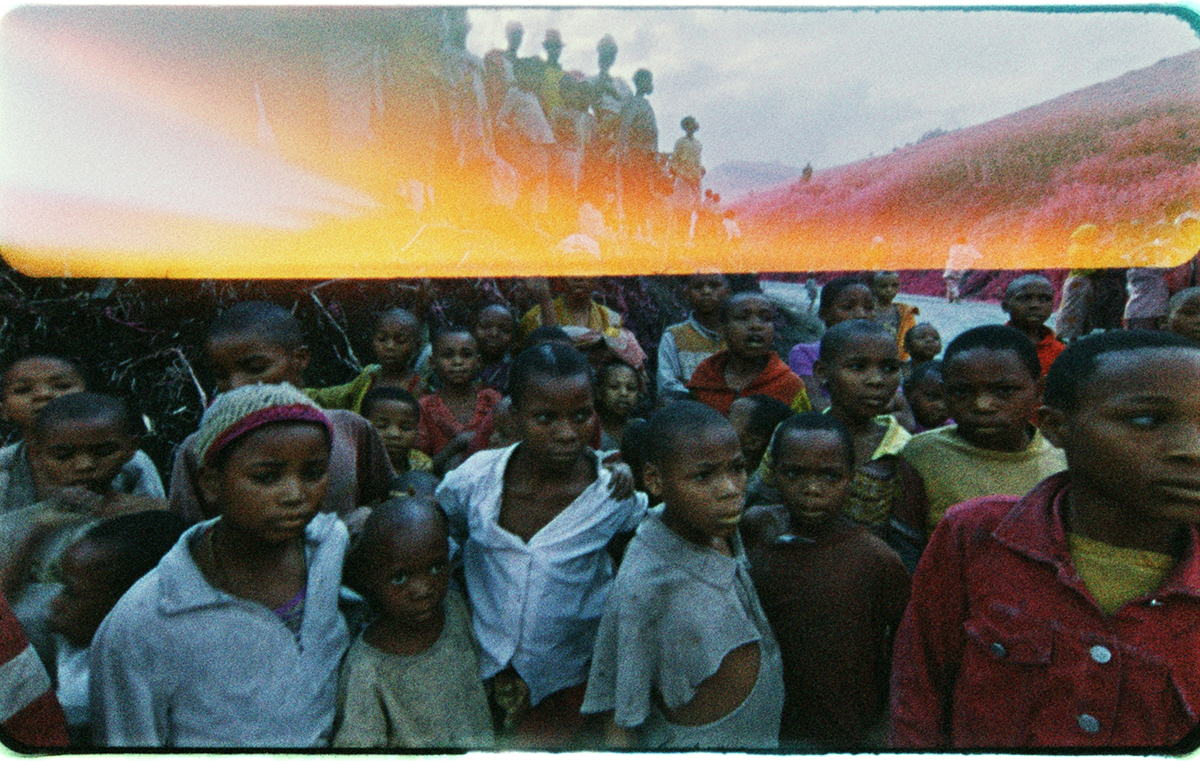

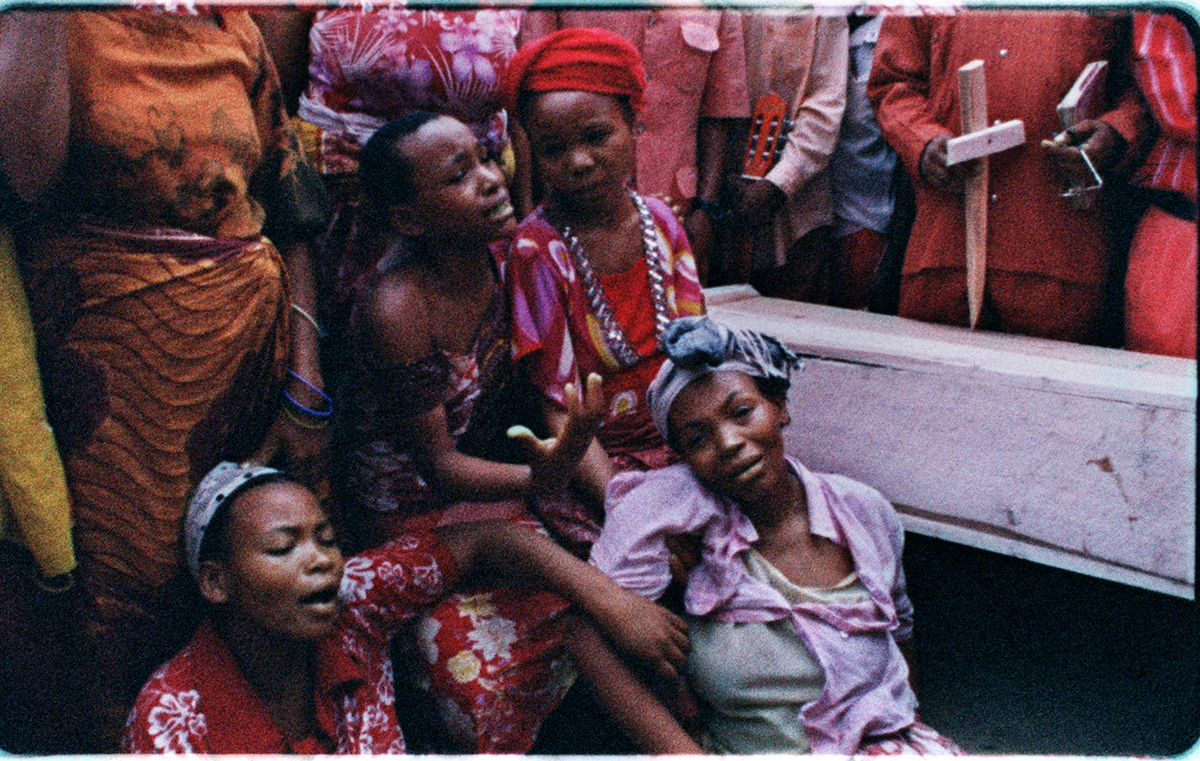

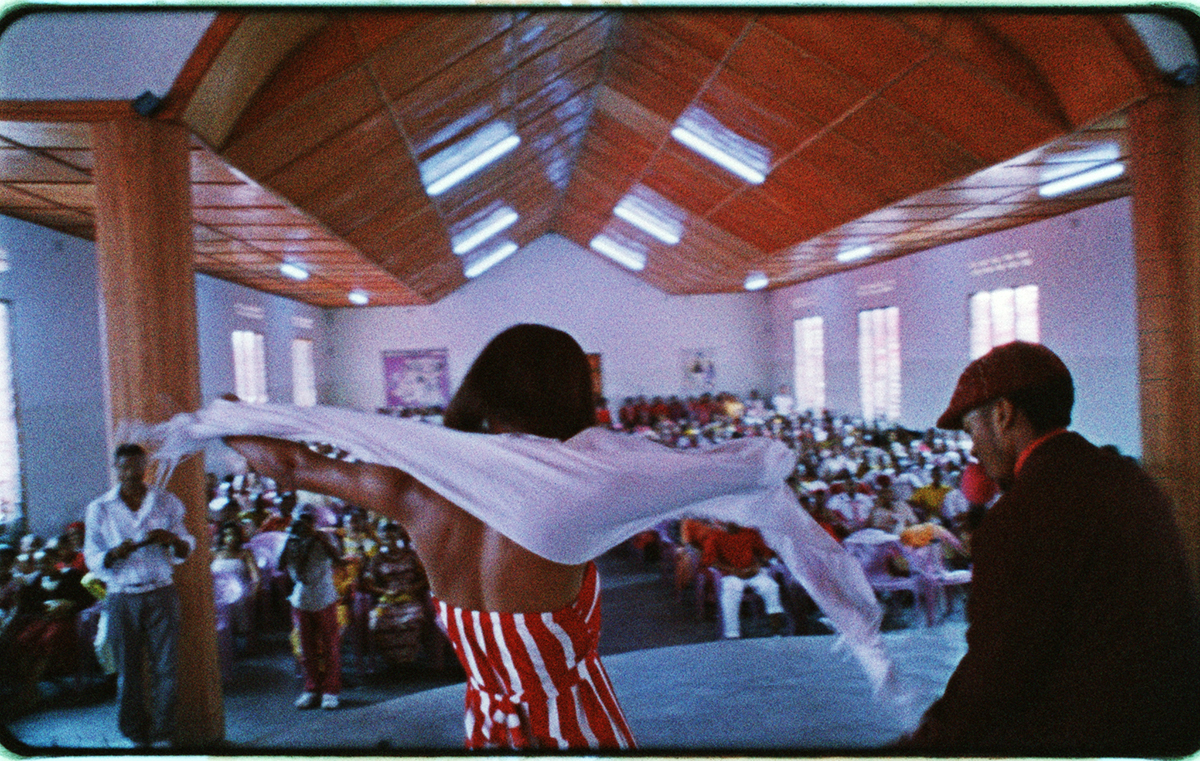

The first images I encounter are photographs of a vivid African landscape— still, majestic, like a sublime romantic panorama. The tints are those of magenta, purple and blue: the artist has used a type of 16-mm film able to record a part of the spectrum of infrared light that is invisible to the naked eye, developed for military purposes and concealed surveillance. I move on to the next room, a dark space with a video installation displayed on six screens. The sounds in the background—pulsating, menacing tones (the audio has been created by Ben Frost from recordings made in the field)—accompany shots of soldiers at their guard posts, corpses lying in the road, women and children coping with the daily tragedy of war. The images pass from one monitor to another—slowing down, speeding up, stopping only to start rolling again, creeping between the folds of the screens like a soldier in hostile territory.

Richard Mosse, The Enclave, 2013.

The videos are in the same colors as the photographs—a palette of reds, pinks and blues—giving the moving images an incredible formal quality (the artist wants to put the viewer on the spot, placing him in front of an insoluble conflict, the one between ethics and aesthetics, between moral conscience and visual enjoyment: is it possible to take pleasure from watching such harrowing and dramatic images?). Beauty is the ultimate aim of Richard Mosse’s art: his work (an artistic operation through and through, lacking the objective character of the journalistic reportage) is a personal evocation of the civil war in the Congo, a narration as realistic as it is imaginative, that veers toward nightmare and hallucination—in certain moments, you feel as if you’re inside a dream, with lightning-fast changes of scene and abrupt visual breaks, while the camera twists and turns rapidly amidst the vegetation and pursues grim-looking extras. The power of art—and, in particular, the effectiveness of Mosse’s work—lies in just this: in its ability to represent what is too terrible to be portrayed or too distressing to be described.

Richard Mosse, Protection, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2012.

Richard Mosse, The Enclave, 2013.

Richard Mosse, The Enclave, 2013.

Richard Mosse, The Enclave, 2013.

Richard Mosse, The Enclave, 2013.

Richard Mosse, The Enclave, 2013.

Richard Mosse, Of Lillies and Remain, 2012.

Richard Mosse, Platon, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2012.

Richard Mosse, Safe From Harm, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2012.

Richard Mosse, Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2012.

Richard Mosse, Suspicious Minds, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2012.

Follow Federico Florian on Google+, Facebook, Twitter.

By the same author:

ArtSlant Special Edition – Venice Biennale

Notes on ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’. A Venetian tour through the Biennale

The national pavilions. An artistic dérive from the material to the immaterial

The National Pavilions, Part II: Politics vs. Imagination

The Biennale collateral events: a few remarks around the stones of Venice