26 November 2013

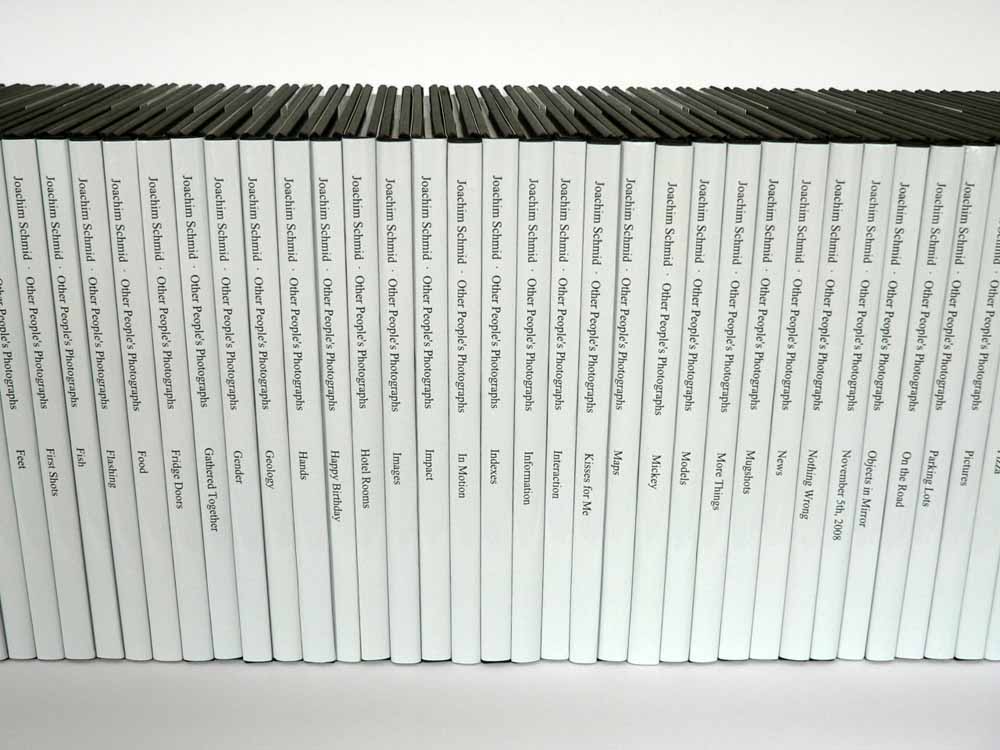

Photographer, artist, archivist: it’s hard to come up with an unambiguous definition of the German Joachim Schmid, pioneer of found photography, who for thirty years has been offering an authorial view of the flow of images produced by our daily existence. Schmid is above all a predator of the lives and gazes of others, someone who seeks them out and finds them in flea markets, antique bookstores or that immense deposit of snapshots to be found on photo sharing sites. He himself recognizes that the internet has represented the only decisive watershed in his work: everything can be found online, and at once. And it is no accident that the 96 volumes of the project Other People’s Photographs are devoted to Flickr. But Schmid’s years of attention to everyday photography has also brought another phenomenon to light, a less evident and probably more disquieting one: the extinction of film and the advent of the digital in recent decades have fundamentally changed the meaning and importance that we assign to these freeze-frames of our life. In the course of the self-publishing that has become his trademark, Schmid has documented a genuine shift in the collective imagination: where there used to be one photo there are a hundred, where there used to be one souvenir we find hundreds of snaps that we forget a minute after we have taken them.

Joachim Schmid, Other People’s Photographs, 2008–2011.

You started working on found photography in the ’80s, and since then found photography-related work has been growing exponentially. How do you compare today with back then when you started?

I think it has changed dramatically. In the early ’80s it was more of an outsider’s practice: there were a few established artists who were allowed to work with found photography, like John Baldessari or Christian Boltanski. And for reasons I don’t completely understand it has become really mainstream now. It’s not a question anymore whether it’s a legitimate practice. If you go to any art school in the UK, Holland or Germany all the students work with found material.

What are the biggest consequences of this expansion?

People often want to show me their work, and then instead of talking about photography they talk about their grandmothers, and that’s one of the problems with snapshot photography. There’s the danger of getting involved personally and that’s the reason why I don’t touch my family’s photo albums or anything like that. I’m not interested in a therapeutic work about my origins or my problems with my family. Some people have these three little photographs of a procession, and then they say “This is my grandmother.” No it’s not your grandmother, it’s just a fucking photograph! There are lots of people who do interesting work, but there are also lots of people who think that grabbing something here and grabbing something there and mixing it up makes something, but often that’s not the case.

Can you recall a moment when there was a switch?

I think it was a slow transition, but the internet definitely helped. It has been more influential than anything else. It’s a different approach, like opening the faucet in your apartment and pictures start coming out. It makes a lot of difference. It’s about searching. You just type in a few words and the search engine throws out hundreds of thousands of pictures and you can just grab them. So it’s not about getting out and looking for something physically, it’s not about the chance encounter, it’s the convenience of working on the keyboard and having everything at your fingertips.

Was it difficult to have your work considered in the early years?

Definitely. It was better accepted in the general art world, but there you had people saying “Hans-Peter Feldmann already did that!” or something like that. In the world of photography it was more like “What does that man want? He doesn’t use a camera? That’s what photographers do, they have cameras, don’t they?” So there was a lot of confusion, but it was also due to the fact that at the time photography was still struggling to be acknowledged as an art form. There were still specialized photography galleries, and it was like “We are artists too, we are artists too!” The price that was paid for getting photography acknowledged as an art form, was that everything else was excluded: we have good photography, that is what artists do, and then we have a lot of bad photography – actually it’s not even photography, it’s just garbage. And they have nothing to do with each other. I see it differently: it can be everything, the very same picture can be used for advertising, it can show up in a newspaper, can play a role in a private context and it can be turned into an art form, and it’s only small manipulations which make that happen, and then shifts of context.

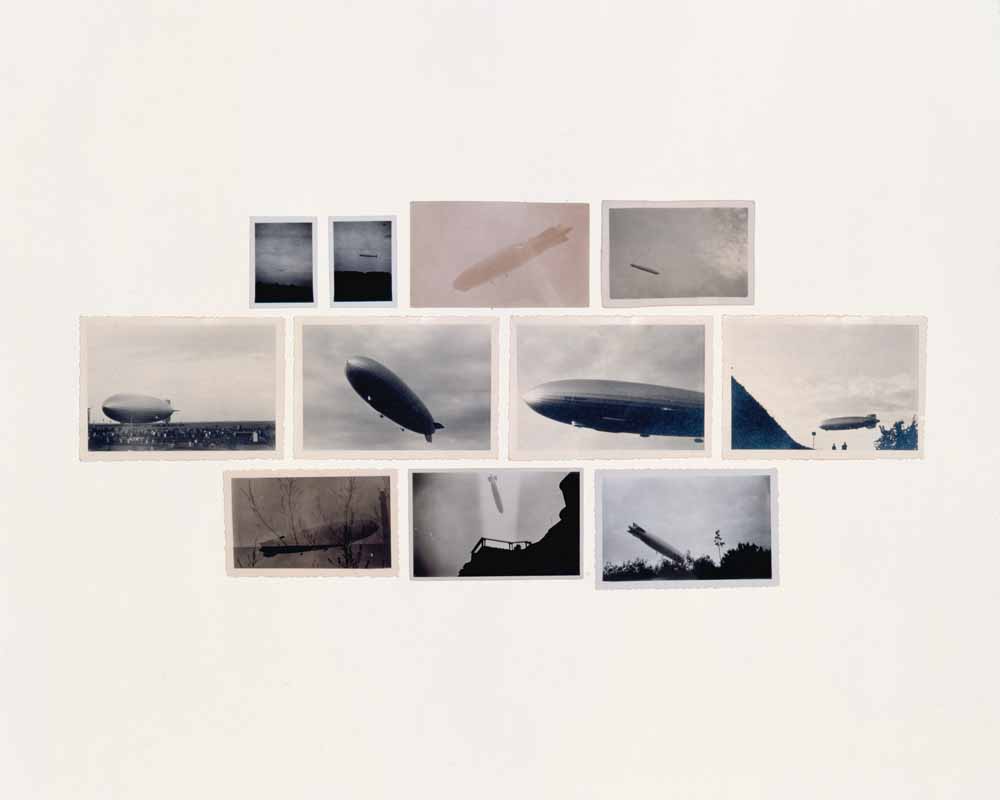

Looking at your work over the years there seems to be a division between two different periods: the physical photographs and the internet. Having done the Other People’s Photographs books, 96 volumes thoroughly exploring Flickr, do you think you might go back to working with physical photographs again?

I’m going back and forth. When I had my first operating internet connection I was fascinated by what was available there, but after a while I got tired of it. I don’t want to spend the rest of my life sitting like a monkey in front of a screen. I’m still going out and looking for stuff in the physical world. Sometimes I’m successful, sometimes I’m not, but it’s not a closed door. One reason why I spent so much time with Flickr is that I made a similar work with Archiv and I was quite happy with the general approach, but I only had access to snapshot photography that was like half a century behind my time.

Joachim Schmid, Other People’s Photographs, Buddies, 2008–2011.

Why this gap in time?

Photographs end up in a flea market only after somebody dies, which means you have a lot of pictures from the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s and ’60s and then it kind of stops, and I wanted to do something with contemporary photographs. Another reason is that you need a lot of pictures to be able to create patterns and to make a display that works visually: even if there are only four or five snapshots on one panel, I need 40 or 50 to put together a series that works visually. Now in the age of online photographs you have an unlimited supply and I get pictures which are still fresh out of the camera: they were maybe uploaded five minutes ago and I have access to them. And that’s the reason I spent so much time on it. Basically Other People’s Photographs is a remake of Archiv in a different situation.

What strategies do you use to find the right images?

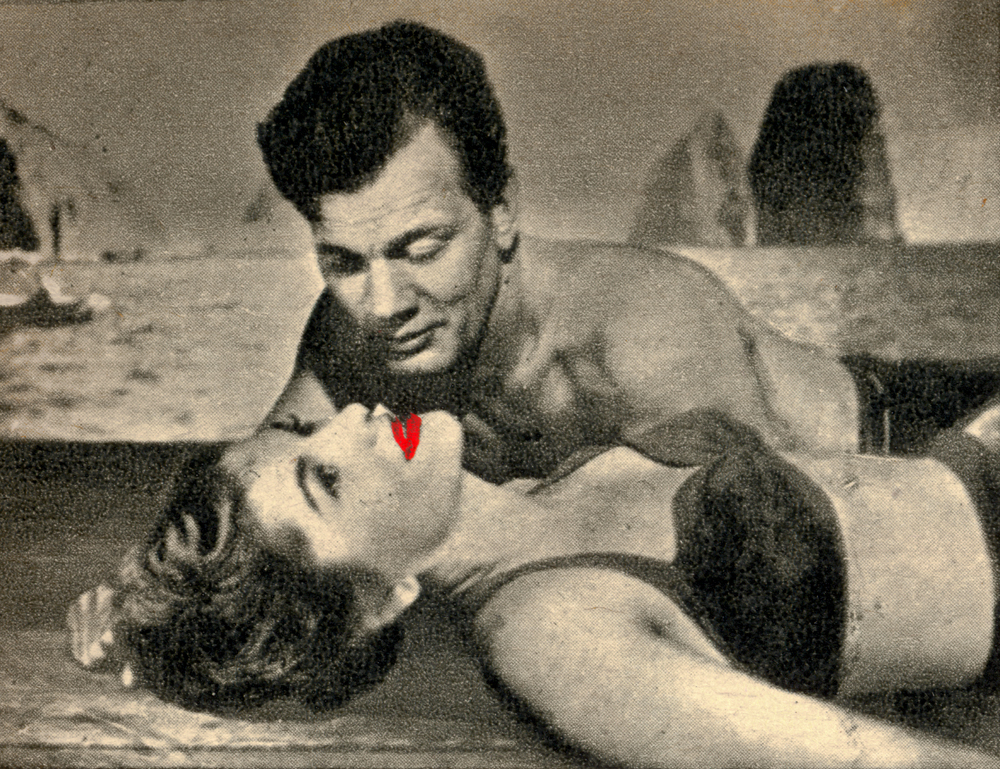

There’s no real strategy, I’m exposing myself to the world and I’m curious to see what’s happening. For a while I was focusing on what was happening on the internet, but I have a life outside the computer. The latest work I did, I was in Portugal for two to three days and I had some two to three hours off and went to a second-hand bookstore in Lisbon. There I found these magazines, and they were magazines about movie stars. It was clear that they had belonged to a young woman who had amused herself coloring the lips of all the actresses in the pictures. I haven’t seen anything like this ever before, but it’s one of those chance findings. You can’t look for that, you can’t think that up. Imagine Lisbon in the ‘50s, a poor society under a dictatorship and no way out, and a young woman starts dreaming, and going to the cinema is her only channel to another world. So when I find something like this, I know immediately it is something I want to work with.

Joachim Schmid, Estrelas Amadas, 2013.

How do you compare Flickr with Instagram, a platform which has also become a sort of photographic style?

I’m not interested in Instagram because, once the project on Flickr was finished, I decided not to touch online photos for a while. It’s not good for your mind if you look at other people’s photographs for ten hours a day. I have seen so many snapshots and I have got so many insights into various people’s lives, people I don’t know at all, including their very intimate life, and after a while it’s like “Ok, let’s breathe for a while.” It can get really compelling, it’s almost like stalking somebody. I had a number of Flickr photostreams that I was following every day, coming from people who use it regularly and upload a lot of pictures every day, and after a while I got addicted to looking at that person’s picture. But it was similar even when working with physical snapshots. Sometimes in a flea market you find a box that is basically one person’s life, and then when you start going into it there are also some letters, some other documents, and after a while you almost start living somebody else’s life. It’s quite fascinating, but then I had to press the emergency button, like “wait, this is not what I want. I want to work on the photographs, I don’t want to reconstruct biographies.” There’s nothing wrong with doing that, but it’s not my work and I didn’t want to go that way.

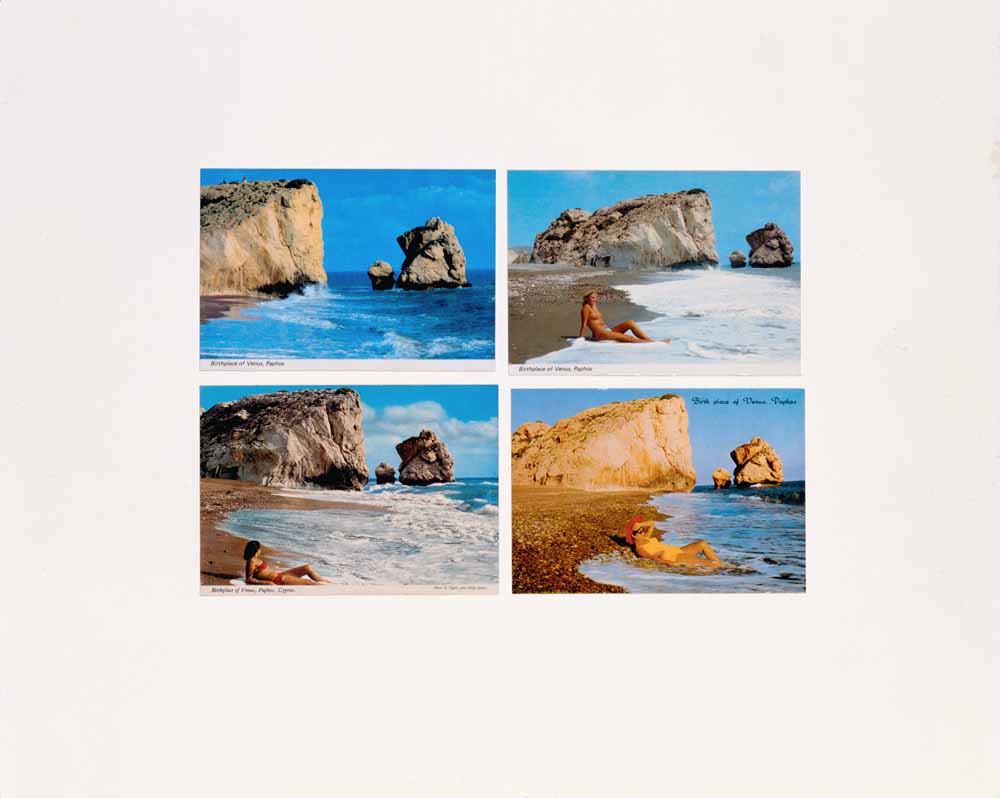

In 1965 Pierre Bourdieu wrote Photography: A Middle-Brow Art in which he talked about how people make photographs. One of the things he analyzed is how people tend to reproduce certain images of themselves, how their images correspond to a certain idea of society. Perhaps today people take pictures in a more private way: there are more and more images, but there’s a less clear dynamic of self-representation.

I think the practice has loosened up tremendously as much as it has widened. People take photographs for no reason at all, it’s just a part of everyday life that nobody thinks about anymore, and the individual picture has become almost completely meaningless. It’s more about a momentary sensation, like “I’m here, good bye.” By contrast, let’s say 50 years ago a family would spend one roll of film on a vacation, or maybe two rolls. They would select the event to photograph much more carefully, they would prepare for it. With a little bit of luck there would have even been a good sense of composition. Now everyone takes hundreds of photographs every day and so the individual picture is devalued completely. And I think many of those photographs will never be seen. People just take them as a whim, in a moment, and then forget about them five minutes later.

Are there one or more photographic subjects that have disappeared over time, certain kinds of photographs people used to take and then stopped taking?

I’m not aware of anything disappearing, but it’s pretty obvious that the proportions are shifting dramatically, and the staged family snapshot is becoming a minority issue, whereas it was predominant until maybe half a century ago. It’s probably due to a different understanding of society. The family hierarchy is not as dominant as it used to be, there’s hardly any traditional family left with one mother, one father and a set of children—people lead all kinds of lives, and that of course is reflected in photography. And then with the arrival of digital photography and the incredible proliferation of production things have become much more casual. You just take a photograph like this or like that. I don’t think that things are disappearing, but the spectrum has become much, much wider. Every cup of coffee has been photographed, every pizza has been photographed. Nobody did that before, and I hope that the pizza photographs may be disappearing at some point.

One of your latest projects, X Marks the Spot is about Dealey Plaza in Dallas, where Kennedy was shot. It’s one of the few times, if not the only one, when you have started from a historical event, a collective memory.

I found these photographs of people standing in the middle of the street there and I was wondering what it was. Then I discovered the webcam sending the live feed of the road, and it was a perfect match. On one side I discovered the snapshots people take and upload, and on the other hand I can watch people taking those snapshots, and the combination of the two I think makes a very nice mix. You see people walking on the spot marked with the X where Kennedy was shot to take the photograph, then you see them walking away to the footpath after the shot. The screenshots of the live feed of the webcam will be combined with the snapshots made by people on the spot.

Joachim Schmid, X Marks the Spot, 2013.

I remember somebody asking you in an interview about 9/11, and you said that you did not make something about it because there’s just too much about it already, and people would jump on you if you made something based on that.

It’s so loaded. The pictures of course are so powerful, they’re extremely present but there’s also today’s madness, today’s fear of terrorism and the paranoia connected with that. I did not find a way to make anything out of it, maybe somebody else did. And I also did not look for it, because it was not my main desire to do something about 9/11. If the Americans want to do something, they should go ahead and do it, but I don’t.

Have you ever thought about doing a comparative work based on professional photography, comparing the clichés and obsessions of the various genres?

I was playing with the idea but eventually I did not do it. Maybe the desire was not that strong. Sometimes I think it would be interesting to do it, but you don’t make many friends if you do something like that. I don’t go to art fairs or galleries anymore, but sometimes when I go to an art fair I think “Really? I saw that at the other gallery round the corner, they all look the same!” There are just a few models and people repeat them. Who do you want to trick?

Many artists pay tribute to whoever helps them, galleries, publishers, etc. But in your case, the way you make your books, the self-publishing thing…

I’m pretty much finished with the publishing world, because I don’t have any respect for those people. It’s really sad how the publishing world changed during the past 20-30 years. Most publishers are not publishers anymore, they are money-collecting agents. They make books which are financed by museums or galleries or sometimes even by the artists themselves. Their curatorial or editorial authority is extremely questionable. It’s a completely corrupt world. When I was young I tried to make a couple of books, but I was not very successful. And I can understand that. If I try to think with the brain of a publisher and look at my proposals, would I publish that book? No, because it’s pretty obvious that only a small number of people would ask for something like that. So I’m not really angry about it, I understand why they don’t publish my stuff. Now I’m really happy that I found access to a technology that allows me to do that. And now the risk is minimal, you can print 100 books of decent quality at little cost and in the age of the internet it’s much easier to find your audience, and for people to find you.

You seem to place value on keeping your publications affordable for your audience.

I think it’s important. A book is the perfect means of conveying an idea or a concept, and in purely pragmatic terms it’s a very democratic way to make art. I’ve never been interested in art books printed on fine paper and things of that kind. I’m interested in the democratic aspect of the book, a book should be affordable for somebody who is a student. It’s fine if there are expensive books too but it’s not my world. I’d rather have 50 small books than one big book.

How do you deal with the copyright issues involved with using other people’s pictures?

I am aware I am working in a grey area. I tend to ignore issues and if there’s a problem I’ll find a way to solve it. It happened two or three times that people complained, not because I had used their photographs but out of fear that I might do so. There have been two occasions when Flickr users were really upset, and one of them managed to find a couple of photographers whose pictures I had used and sent them an email, saying “Are you aware that Joachim Schmid is using your work?” And they actually contacted me, but nothing happened. Indeed one of them said “I’m so glad that one of my photographs is in your book! Can I get a copy of it?”

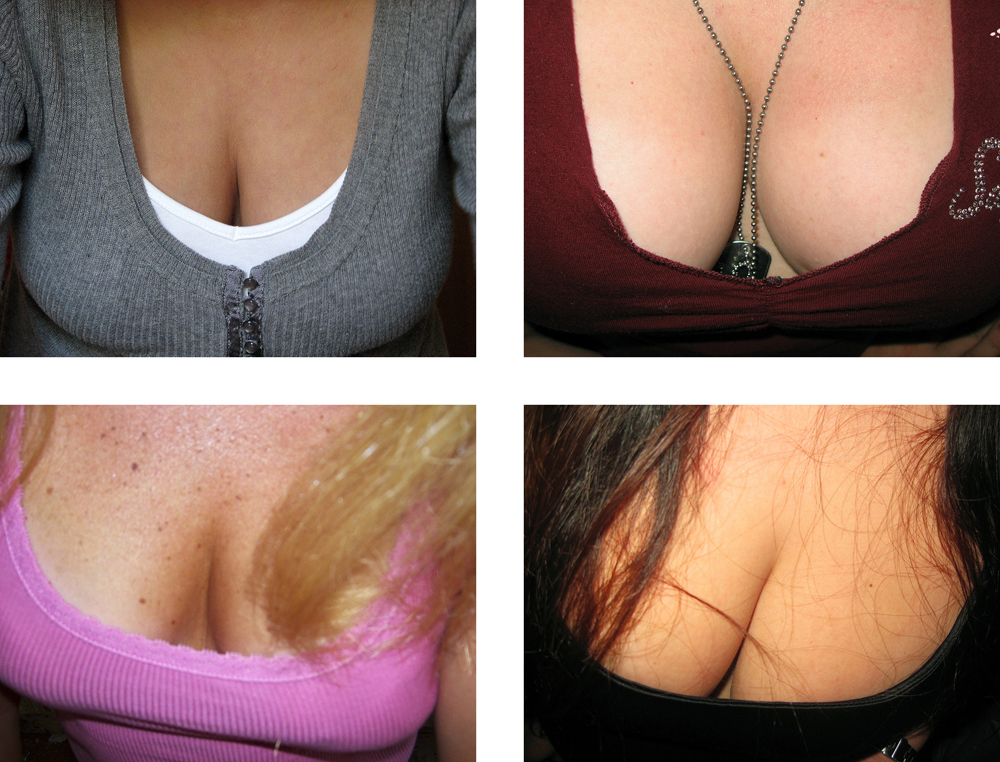

Joachim Schmid, Other People’s Photographs, Cleavage, 2008–2011.

On many occasions you have mentioned the fact that in your work there are actually photographs you took yourself, that sometimes you shoot some pictures to fill in the gaps in your projects.

In the Other People’s Photographs series quite a number of photographs are by myself, and there’s a reason: with a series of sunsets it’s easy, there’s an unlimited supply, so I wouldn’t need to shoot a sunset photograph. But let’s say I have decided to make a book about a certain subject because it’s interesting, but I don’t have thousands of pictures about that. Each book contains 32 photographs, but in order to balance that as a group and to have a series of spreads that look good you need at least 100-150 to pick from. And sometimes I want to include something but I don’t have a matching counterpart, so then I just take it myself. I could spend another two or three days in front of the computer and find the matching thing, but it’s just too much time, and in the end it looks the same.

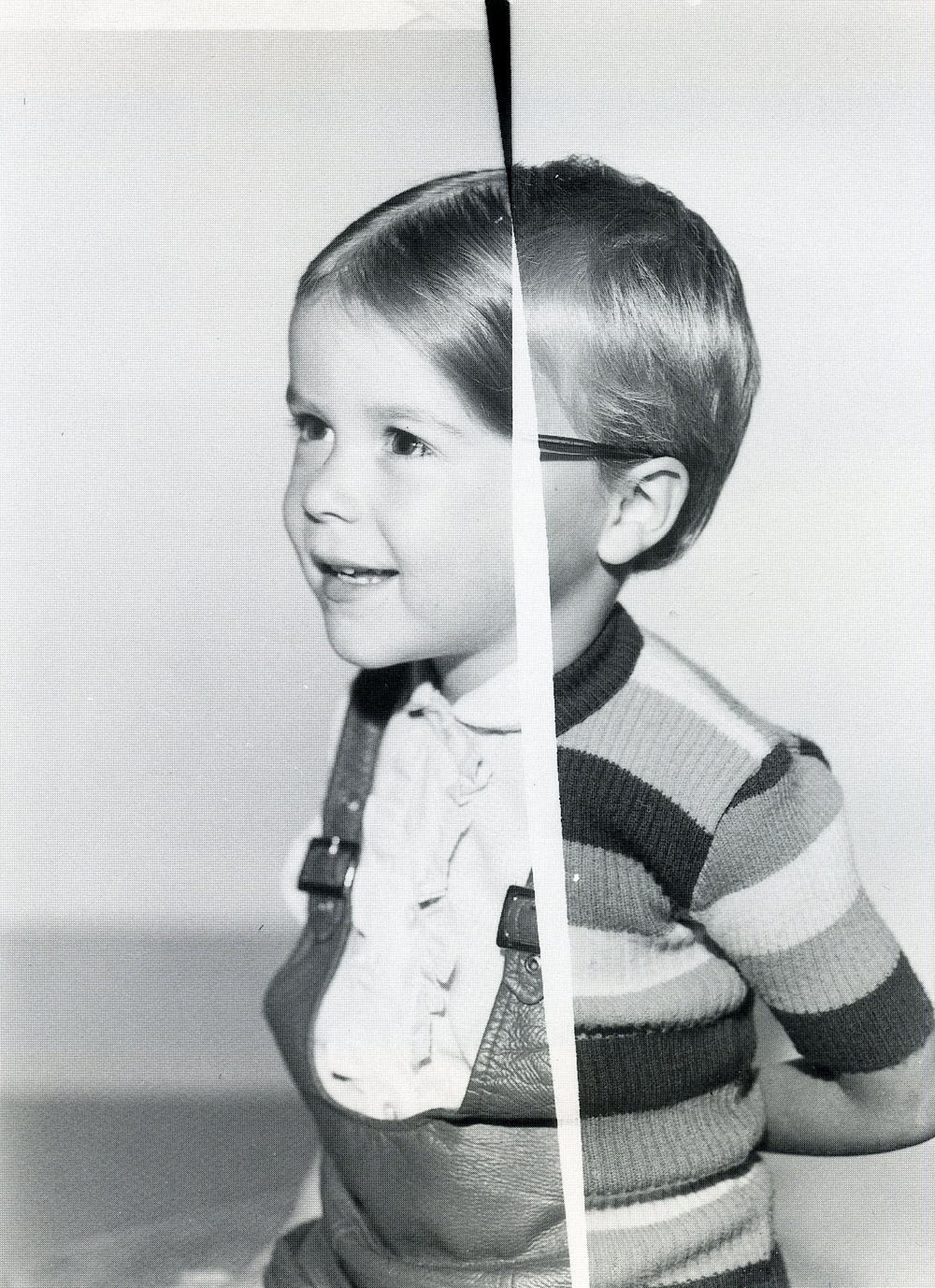

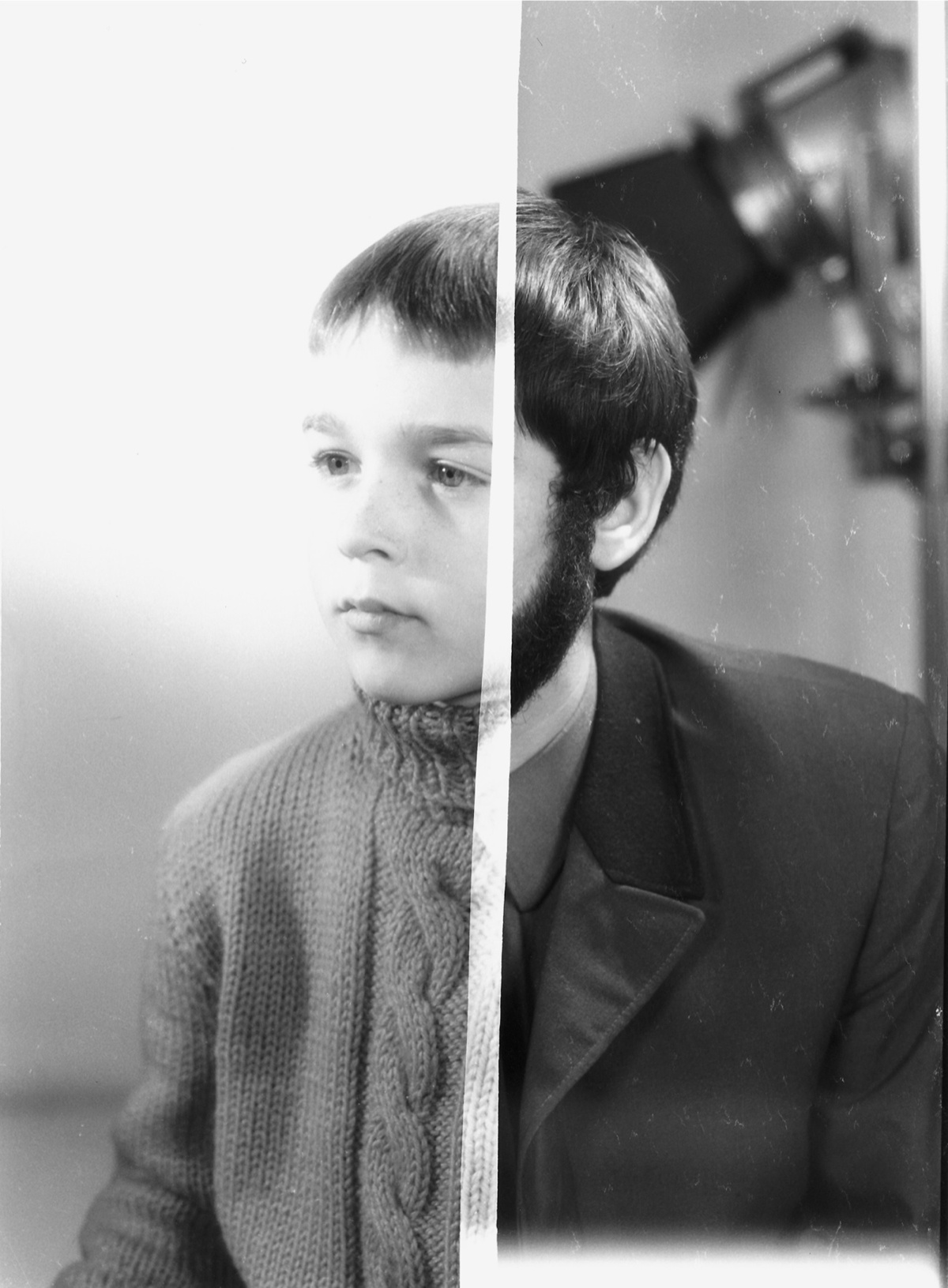

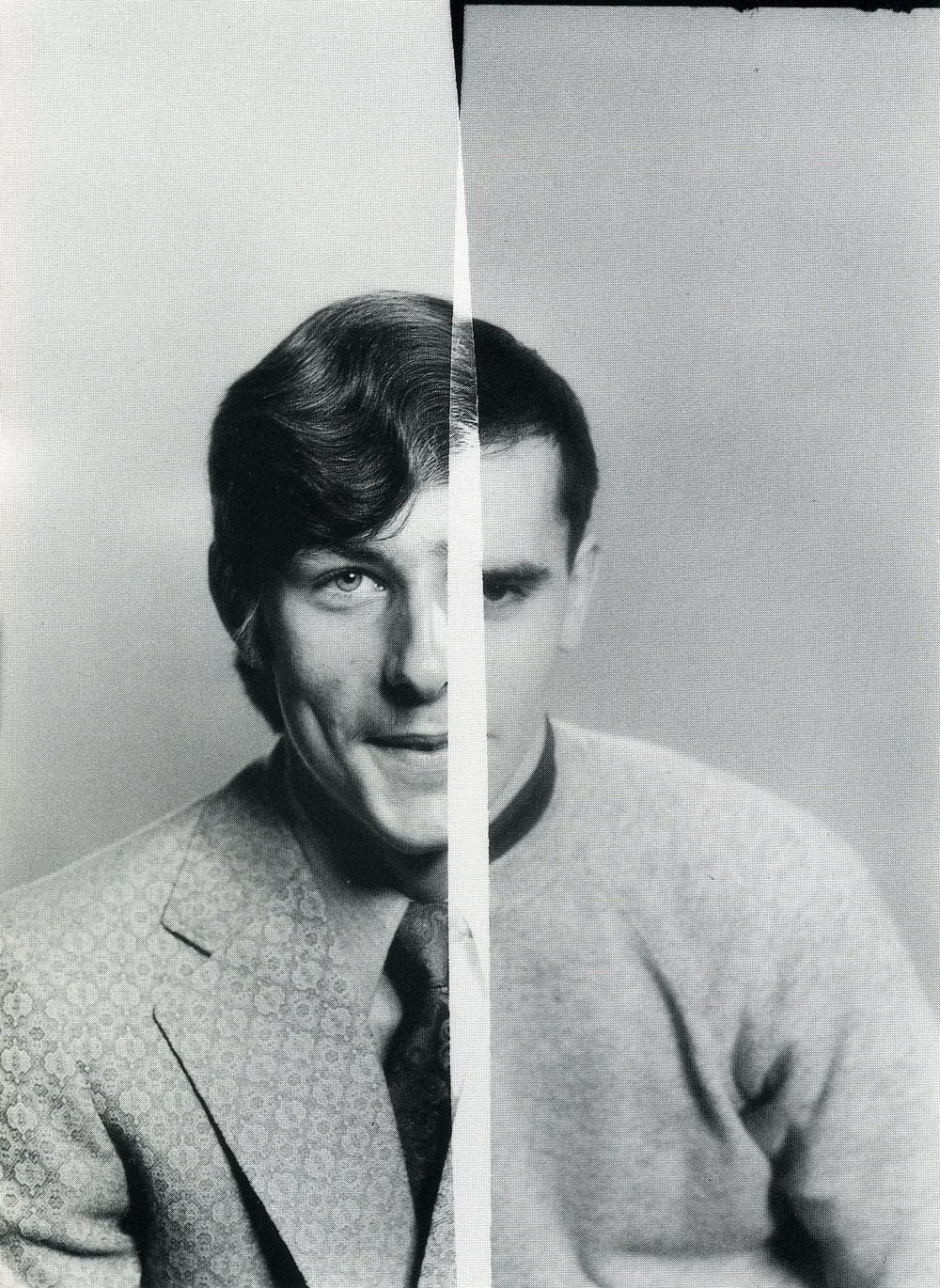

Joachim Schmid, Archiv #1, 1986.

Joachim Schmid, Archiv #122, 1988.

Joachim Schmid, Estrelas Amadas, 2013

Joachim Schmid, Other People’s Photographs, Flashing, 2008–2011.

Joachim Schmid, Archiv #606, 1994.

Joachim Schmid, Photogenetic Drafts, 1991.

Joachim Schmid, Photogenetic Drafts, 1991.

Joachim Schmid, Photogenetic Drafts, 1991.

Joachim Schmid, Photogenetic Drafts, 1991.

Joachim Schmid