12 June 2013

Despina can be reached in two ways: by ship or by camel. The city displays one face to the traveler arriving overland and a different one to him who arrives by sea.

When the camel driver sees, at the horizon of the tableland, the pinnacles of the skyscrapers come into view, the radar antennae, the white and red windsocks flapping, the chimneys belching smoke, he thinks of a ship; he knows it is a city, but he thinks of it as a vessel that will take him away from the desert, a windjammer about to cast off, with the breeze already swelling the sails, not yet unfurled […].

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (Chapter I: “Cities and desire. 3”)

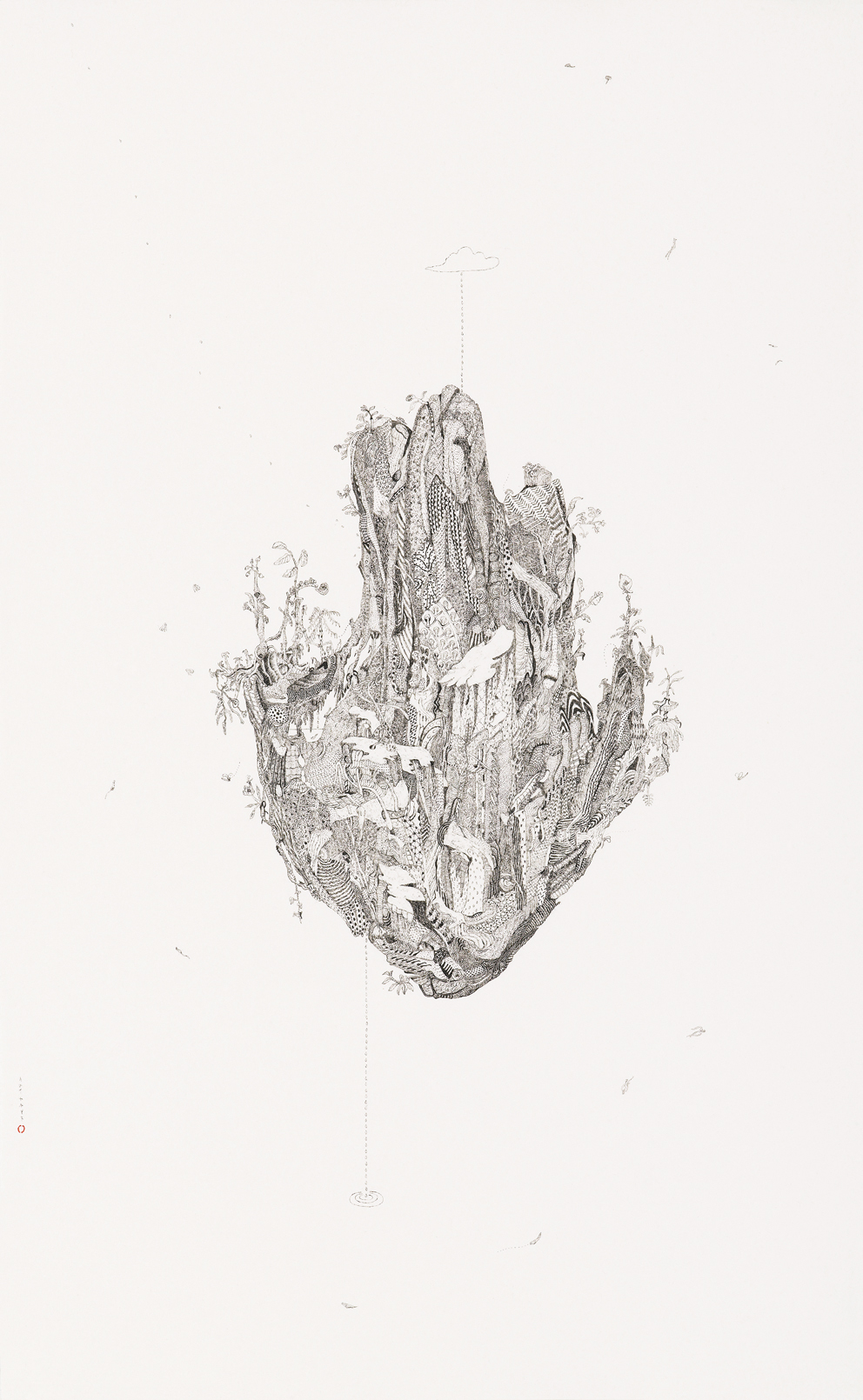

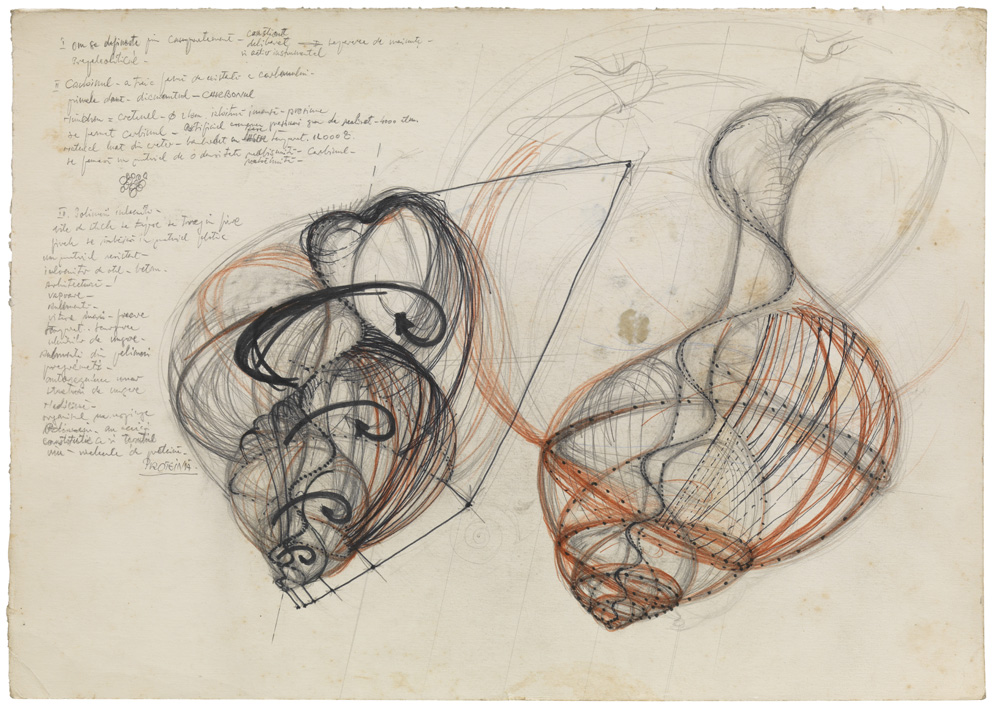

I am in the Arsenale, the ancient Republic of Venice’s complex of shipyards. A passage from Dante’s Inferno echoes in my: I imagine the spaces of the building boiling with black pitch, the substance that was used by the Venetians, right here, to tar ships damaged in battle. I turn into the Corderie—the place where ropes were once made for the boats—and look for a first safe landfall. And it’s at this point that I find Marino Auriti’s Encyclopedic Palace, ideal introduction to the first section of the exhibition. I’m struck by the central tower, halfway between a Mayan stepped pyramid and an ornate art deco skyscraper, container for the world’s knowledge and symbol of this Biennale—a jumble of disparate forms, images and objects, united in a single cabinet of curiosities. I continue along my encyclopedic route, a sort of progression (to use Gioni’s words) “from natural to artificial forms”—a Wunderkammer of eccentric and incomplete character. And so I come to a series of samples and taxonomies of nature: Eliot Porter’s photographs of birds, the heart-shaped forests of Lin Xue, the spiral snails of Ştefan Bertalan. They are highly subjective inventories, pervaded by a romantic impulse and remote from any precise operation of positivistic mapping of reality.

Pawel Althamer, Venetians, 2013. 55th International Art Exhibition, Il Palazzo Enciclopedico, la Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: Biennale di Venezia.

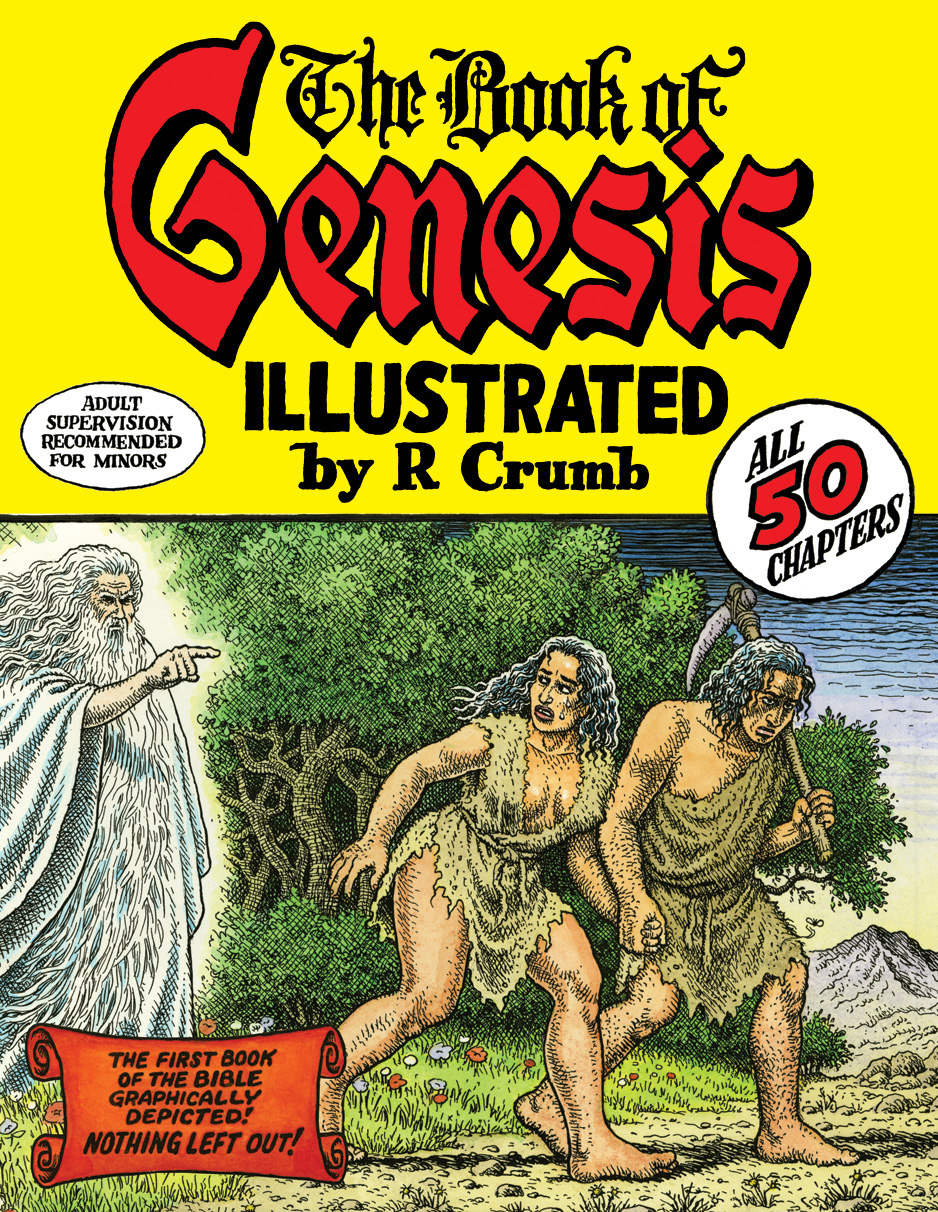

I wander around the objects on display in the rooms of the Corderie, an erratic compendium of works of art, idol-fetishes and ethnographic exhibits. Roberto Cuoghi’s mighty meteorite-menhir towers in the middle of one room: it seems to be alluding to a primordial Olympus—making me think of the material consistency of a remote universe. I get a brush-up on the history of this universe from watching Camille Henrot’s video, a kind of contemporary Genesis in a pop version—proposed again, a few rooms later, in the guise of an epic graphic novel by Robert Crumb. The chronicling of the beginning of the world portends the image of its end: and so I run into the spindly souls of Pawel Althamer’s Venetians, boneless portraits of the city’s inhabitants, roaming as if in limbo before reuniting with the material from which they have been molded. Immediately a collection of puppet-bodies, dolls and ritual masks is laid out before my eyes: this is the little cabinet of curiosities prepared by Cindy Sherman, an experiment in meta-curation intended to generate unease and wonder in the curious viewer.

Eliot Porter, Chipping Sparrow, Great Spruce Head Island, Maine Dye transfer print from Birds in Flight portfolio, 1979. © 1990, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Bequest of Eliot Porter. Courtesy of Daniel Greenberg and Scheinbaum & Russek Ltd., Santa Fe, New Mexico.

R. Crumb, The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R. Crumb, 2009. © Robert Crumb, 2009. Courtesy the artist, Paul Morris, and David Zwirner, New York/London.

I walk past the hysterical microcosm of Ryan Trecartin’s videos, peopled by a parade of histrionic and unlikely characters—compendium of an exaggerated humanity, that of the society of the spectacle. For a moment I pause in front of Yuri Ancarani’s video, a mechanical choreography staged by the limbs of a surgical robot. And it is precisely the precision, the accuracy of these robotic movements that puts me in the right frame of mind for the sculpture that concludes the route through the Arsenale: Apollo’s Ecstasy by Walter De Maria. The diagonal sequence of cylindrical gilded bronze rods sketches out a catalogue of harmonic forms—creating for a moment the illusion of the possibility of a rigorous classification of reality. An “Apollinian” ideal, this last, or an Enlightenment dream, whose insubstantiality appears to be heralded by the tired sound of wind instruments in the distance: they are the horns of Ragnar Kjartansson’s “Dionysian” boat, the S.S. Hangover, stranded in the basin of the Gaggiandre. What comes out of the mouths of the brass instruments is a modern hymn to Bacchus—expression of an ecstatic, highly imaginative energy that induces in people a feverish (and never fully realizable) desire to sum up the whole world in an image. Slowly, the vessel leaves its moorings and its sails slip behind the pillars of Sansovino’s arches. It is time to change course and head for the Giardini.

Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue, 2013. Courtesy Camille Henrot e/and Kamel Mennour, Paris.

![Vlassis Caniaris Paratirit・ [Observer], 1980/2005](http://www.klatmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Klat_V_Caniaris_1.jpg)

Vlassis Caniaris, Paratirit・ [Observer], 1980/2005. 55th International Art Exhibition, Il Palazzo Enciclopedico, la Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Francesco Galli. Courtesy: Biennale di Venezia.

Lin Xue, Untitled (2012-13), 2012. Photo: Eddie C.Y. Lam. Courtesy: LIN Xue e/and Gallery EXIT

Walter De Maria, Apollo’s Ecstasy, 1990. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Stefan Bertalan, Snails. Courtesy Johnen Galerie.

Follow Federico Florian on Google+, Facebook, Twitter.

Dello stesso autore / By the same author: ArtSlant Special Edition – Venice Biennale

Notes on ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’. A Venetian tour through the Biennale

The national pavilions. An artistic dérive from the material to the immaterial

The National Pavilions, Part II: Politics vs. Imagination

The Biennale collateral events: a few remarks around the stones of Venice