19 June 2013

From there, after six days and seven nights, you arrive at Zobeide, the white city, well exposed to the moon, with streets wound about themselves as in a skein. They tell this tale of its foundation: men of various nations had an identical dream. They saw a woman running at night through an unknown city; she was seen from behind, with long hair, and she was naked. They dreamed of pursuing her. As they twisted and turned, each of them lost her. After the dream they set out in search of that city; they never found it, but they found one another; they decided to build a city like the one in the dream.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (chapter III: Cities and desire, 5)

I walk along the tree-lined avenue of the Giardini, in the direction of the Central Pavilion. I can make out its white geometric façade, with the unmistakable pronaos of columns: this is the beating heart of the Biennale and it is here that the second section of The Encyclopedic Palace has been mounted. I cross the threshold of the building and find myself in a circular room, an almost mystical setting. My gaze loses itself in a riot of superhuman forms and apocalyptic images: I look at the illustrations of Carl Gustav Jung’s Red Book, the work to which the famous Swiss psychoanalyst devoted over sixteen years of his life. The manuscript contains transcriptions of his self-induced hallucinations, accompanied by a delirious set of drawings – a diary of the obsessions and flights of imagination of a prophetic and visionary mind. I come across the plaster face of Breton sculpted by René Iché—death mask or representation of a surrealist ecstasy—and watch the ritual dirge staged by Tino Sehgal’s performers; a little further on, the colored drawings of Rudolf Steiner’s blackboards call to mind the esoteric transports of Anthroposophy, a utopian attempt to apply the modern scientific method to the spiritual world.

![Carl Gustav Jung The Red Book [page 655], 1915-1959](http://www.klatmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Klat_Carl_Gustav_Jung.jpg)

Carl Gustav Jung , The Red Book [page 655], 1915-1959. © 2009 Foundation of the Works of C.G. Jung, Zürich. First published by W.W. Norton & Co., New York 2009.

The rooms of the Central Pavilion follow one another without order: what holds sway here is the unraveled reality of dreams. I run into the monstrous drawings of Christiana Soulou, inspired by Borges’s Book of Imaginary Beings—a fantastic bestiary contiguous with that of Levi Fischer Ames, composed of small and finely worked sculptures of fabulous beasts. As in a Jungian session of active imagination, dream leads to trauma, and trauma leads back to childhood: I wander around the spectral doll’s houses of Andra Ursuta, reproductions in miniature of the rooms in which the artist lived as a child. They are relics of a troubled past, haunted by invisible nightmare presences.

Levi Fisher Ames, The Gillytu Bird and Ring Tailed Doodle Sockdologer Captured in Minnesota Weight 700 lbs (shadowbox), c. 1896-1910. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

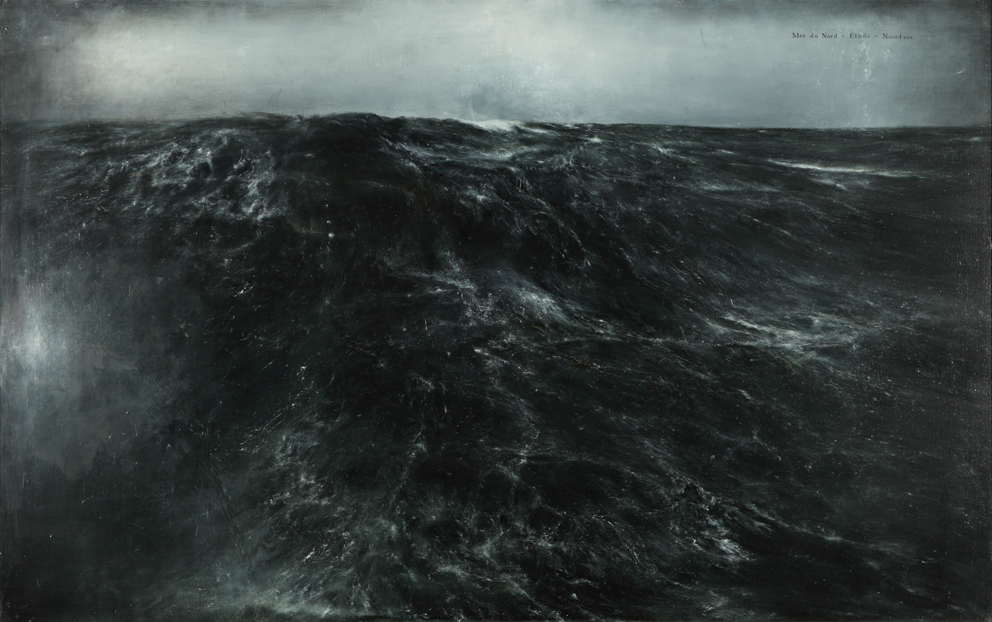

By now I’m almost at the end of my visit, my brief journey through the encyclopedia of the imaginary. Shortly before reaching the entrance of the building again, I find the splendid seascapes painted by Thierry De Cordier. I peer at the murky material of which they are composed, as if they were remains of an ancient geological era. They make me think of surreal dream settings, inhabited by menacing waves on the point of turning into solid strata of rock. The images come to the surface like repressed memories, forming an archive of inner landscapes—the ultimate encyclopedic attempt to map the hazy territory of the spirit.

Thierry De Cordier, Mer Montée, 2011. Private Collection, Belgium. Courtesy the Artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Photo: © 2013 Dirk Pauwels, Gent.

Hilma af Klint, The Dove, no. 12, Series UW, 1915. Courtesy The Hilma Af Klint Foundation.

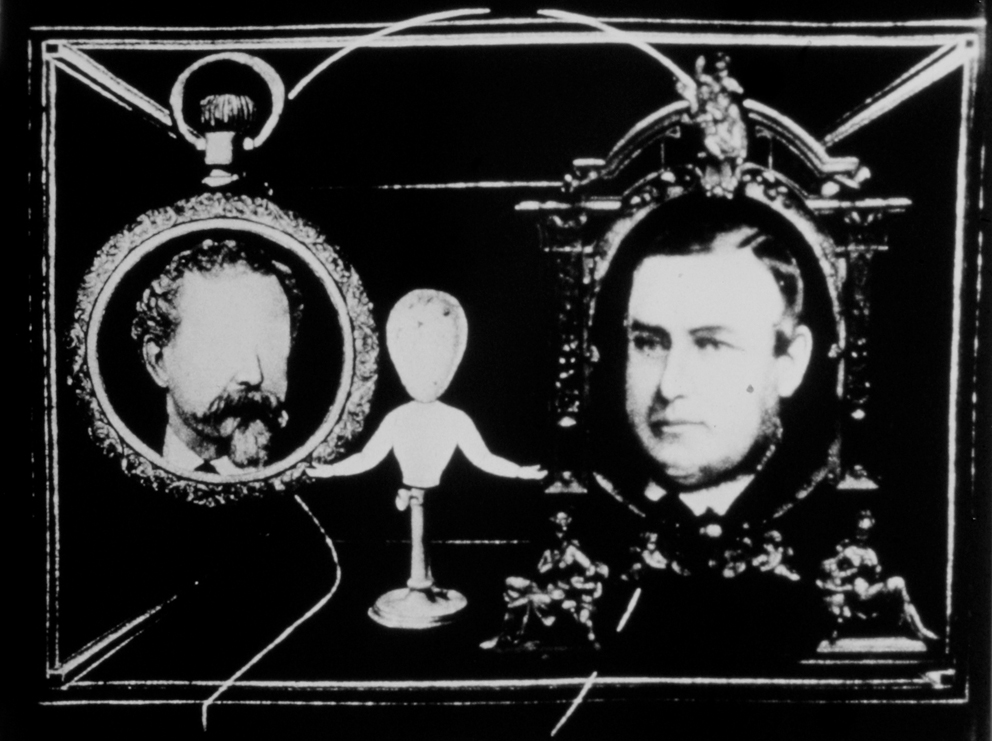

Harry Smith, Film No. 12 (Heaven and Earth Magic), 1959-61. Copyright Anthology Film Archives.

Melvin Moti, Eigenlicht, 2012. Courtesy the artist and Meyer Riegger.

Roger Hiorns, Untitled, 2013. Courtesy: The artist; Corvi-Mora, London and Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam. Photo: Marcus Leith Photography. © Roger Hiorns.

Follow Federico Florian on Google+, Facebook, Twitter.

Dello stesso autore / By the same author: ArtSlant Special Edition – Venice Biennale

Notes on ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’. A Venetian tour through the Biennale

The national pavilions. An artistic dérive from the material to the immaterial

The National Pavilions, Part II: Politics vs. Imagination

The Biennale collateral events: a few remarks around the stones of Venice