10 October 2017

Gio Ponti’s paradoxes. He wanted to create a “chair-chair, devoid of adjectives” and ended up inventing the Superleggera, famous precisely for that epithet which sums up its exceptional character in five syllables (or just three in English: “Superlight”). The contradiction is in reality only apparent—the adjectives shunned by Ponti were stylistic ones: he didn’t want a modern or rational or organic chair, he just wanted a chair that would be a chair—but it is useful for describing the two souls of this celebrated product of Italian design. On the one hand, in fact, the Superleggera reveals its anonymous origin, as a reworking of the typical Chiavari chair (known as the Chiavarina), fruit of the simplicity of Ligurian craftsmanship, which Ponti adapted to suit modern tastes. A bit like Vico Magistretti did with the Carimate (1960), inspired by the classic chair used in the trattorie of Brianza. On the other, it had already been catapulted into the era of contemporary design, thanks to a creator who was anything but anonymous, capable of exalting its essentiality to the point of turning into a slogan as pointed as its legs. A verbal slogan, by way of that prefix which in Italy anticipated by a decade the Superarchitettura of the much younger Superstudio, a theory that did not emerge until 1966. And then a graphic one: the Superleggera is the epitome of a chair, made up of a seat, a back and four thin legs that look like they came out of one of Saul Steinberg’s cartoons.

In the fifties the unfinished structures of the chairs were transported to Liguria on the roof of a Fiat 1100 to be fitted with rattan seats. Archivio Storico Cassina.

In 1949, when he started to work on it with the craftsmen at Cassina, Ponti was thinking of furniture for everyone, and thus of a chair that would be “at once light and strong, the right shape and low in cost.” A “Cinderella chair […] virginal and innocent” that at the outset, in 1952, was simply called Leggera. Just as Cinderella went to the king’s castle in the well-known fairy tale, the chair went to the palace—the Palazzo del Triennale in Milan—and met with success there thanks to its simplicity. Ponti explained: “In the inventive frenzy of our time, in the creative restlessness, in the eagerness to express ourselves through the form of a nail, we have moved so far away from spontaneity, from truth, from the naturalness and simplicity of things, that the appearance of something that is just right, spontaneous, true, natural and simple is seen as astonishing and proves a complete and unexpected success.” After entering the Palazzo, the Cinderella chair would no longer be the same. It wouldn’t change its character, but it did become more beautiful and sophisticated. So that its sections, originally circular, turned unmistakably triangular, and just 18 millimeters thick.

699 Superleggera, design by Gio Ponti for Cassina, 1957.

In 1957 the Leggera became Super, just in time for the economic boom. Ponti, a great communicator, knew that design—by this time a reality in Italy too—needed to be presented in an effective way. Here the magic spell was cast by Giorgio Casali, photographer of Domus magazine, who made the chair’s lightness tangible in his famous picture of a boy holding it aloft with just one finger. But lightness could be equated with fragility, in contrast to the solidity (and heaviness, we would say) of the furniture of the past. Don’t worry: “If you go to Cassina,” wrote Ponti in 1952 “you will be treated to the stirring sight of these chairs being tossed in the air and falling back to the ground from dizzy heights, bouncing and never breaking […]. Entering their factory is dangerous because the chairs are continually flying around in these incredible tests.” And so even the manufacturing process was turned into performance, storytelling, publicity. Ponti was a genius. Those 1700 grams of ash wood and rattan became an icon.

699 Superleggera, design by Gio Ponti for Cassina, 1957.

And then a familiarity with the work of the Milanese architect opens up different levels of interpretation that make its design resonate with all the rest. If it was ergonomics that induced him to put a bend in the back, and if it was statics that made him incline the legs inward, we cannot fail to notice the perfect correspondence between these deformations and Ponti’s theory of the crystal, in which straight profiles grew angular and turned into closed, diamantine forms. From a formal point of view there is a similarity between the broken lines of the Superleggera and the plans of the Pirelli Tower, the Villa Planchart in Caracas and the Italian Institute of Culture in Stockholm, all works of the fifties and all sharp-edged like the chair. But this is not a matter of formalism (or perhaps it is, but well explained): “In creating the Superleggera,” wrote Ponti, “I followed the age-old technical process of moving from heavy to light: removing material and dead weight, marrying form with structure as far as possible, but sensibly and without displays of virtuosity.”

699 Superleggera, design by Gio Ponti for Cassina, 1957.

The Superleggera has been a stimulus for many designers. It was the inspiration, for instance, of Riccardo Blumer’s Laleggera (Alias, 1996), which weighs a little more (2.3 kg) but is stackable, and the Superlight designed by Frank Gehry (Emeco, 2004), in aluminum. But an echo of the original can be heard in many other places. Such as Jasper Morrison and Naoto Fukasawa’s exhibition-manifesto of 2006, entitled Super Normal: a paean to the capacity to combine a reassuring normality and something unexpected, the archetype (the Chiavarina) and its surpassing, tradition and modernity. As it happens, a few years ago Morrison designed the Trattoria Chair (Magis, 2009), a revamping of the popular seat. This year the ex-Cinderella has seen 60 winters—there would be even more counting the first experiments, but you mustn’t ask a lady her exact age—and has donned a special dress in celebration. Cassina has come out with a model in a limited edition (60 pieces): a red structure and a fabric embroidered by the Dutch artist Bertjan Pot that plays, it goes without saying, on the theme of the triangle.

699 Superleggera, designed by Gio Ponti for Cassina, 1957. Stacked. Courtesy: Archivio Cassina.

699 Superleggera, design by Gio Ponti for Cassina, 1957. Courtesy: Gio Ponti Archives. Photo: Giorgio Casali.

699 Superleggera, design by Gio Ponti for Cassina, 1957. Courtesy: Gio Ponti Archives.

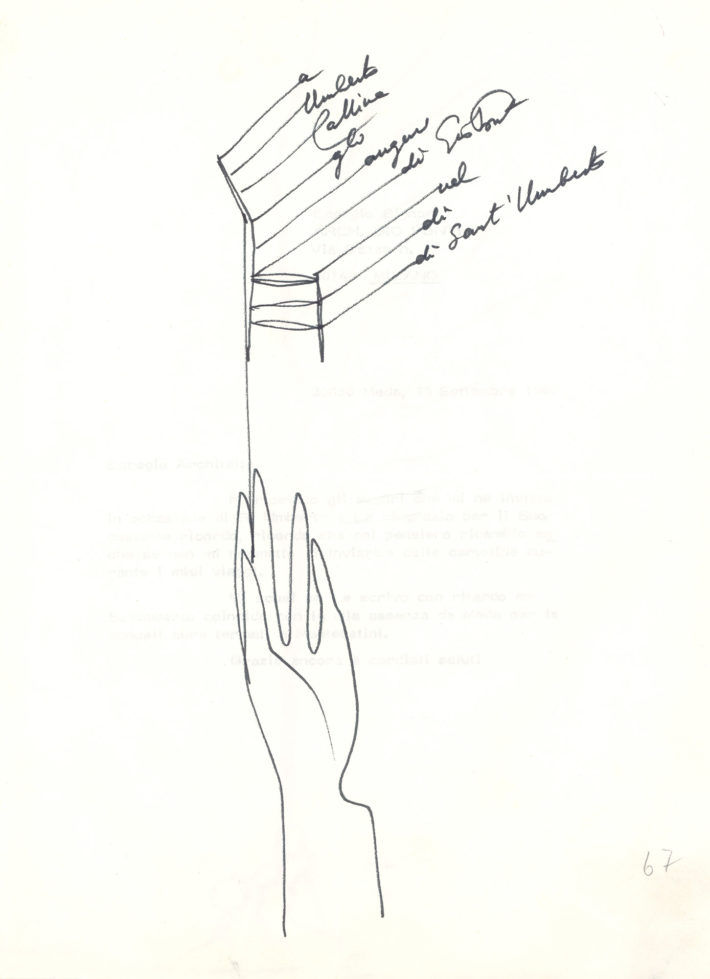

This letter with a drawing sent by Gio Ponti to Umberto Cassina on his name day bears witness to the close friendship between the two men. Courtesy: Archivio Storico Cassina.

Limited edition of Gio Ponti and Cassina’s 699 Superleggera upholstered with Bertjan Pot’s Boxblocks fabric, 2017.

Limited edition of Gio Ponti and Cassina’s 699 Superleggera upholstered with Bertjan Pot’s Boxblocks fabric, 2017.

699 Superleggera, design by Gio Ponti for Cassina, 1957

699 Superleggera, design by Gio Ponti for Cassina, 1957.