31 May 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Martí Guixé’s turn.

Klat #05, spring 2011.

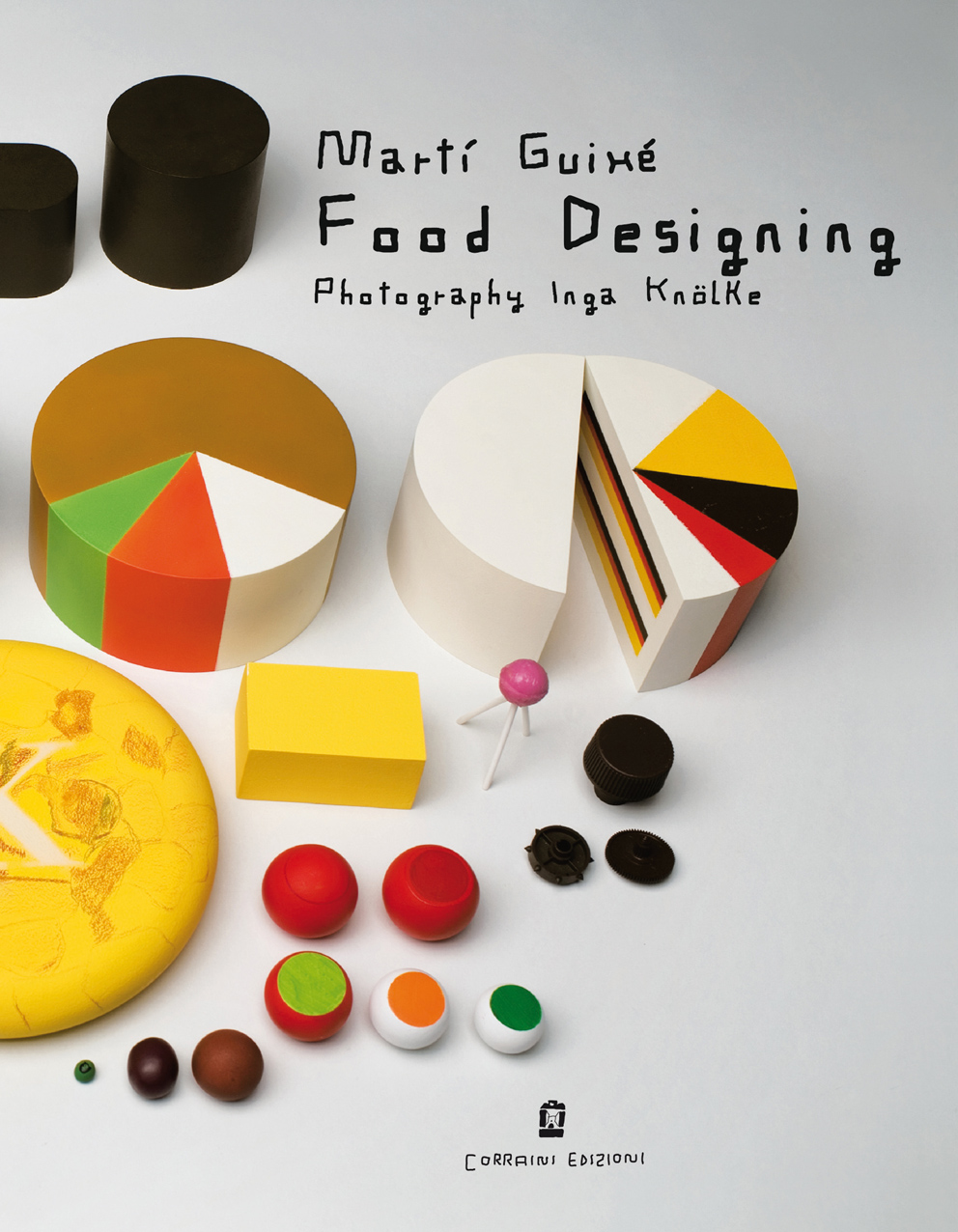

His Food Designing was placed third at the Gourmand World Cookbooks Awards in 2010. Which means that a publication which has nothing to do with traditional books on cooking, constructed as it is around the theme of “designed food,” was given a prize despite not belonging to the same genre as all the other publications in the running. Thinks like this keep happening in Martí Guixé’s career, which is littered with unexpected successes and super-amusing episodes (as he would put it). His delightfully visionary ideas continue to be picked up by small and large companies that are willing to bet on the least classifiable of designers. Conscious that he can be destabilizing, but not at all worried about it and at peace with all his contradictions, Guixé goes on coming up with thoughts (rather than forms), between Barcelona and Berlin, without a real studio and living an insistently and indispensably nomadic existence. Our meeting took place during an interlude in Milan, over two meals, seeking to investigate his work, from the origins to the latest projects.

Something often happens to the little men you draw to narrate many of your projects (that, in the end, become an integral part of those projects. You sum it up by writing: “Aura comes!” What sort of feeling hits your characters at that moment?

In English there is a word, “insight” (its German counterpart is “einsicht”), that pretty well describes what I mean by “Aura comes”: I’m referring to a sort of enlightenment, what the marketing people might call the “ah-ha effect,” or something like that. It often takes a minute or two to grasp the sense of my operations (though they seem very simple to me!), so “Aura comes” means, first of all: “Wow, I got it!”. But then “comer,” in Spanish, means “to eat,” so the word game goes a bit further: the satisfaction of understanding something can be described with the expression “eat the aura,” which works even better, given the fact that I often design food! In the end, in the association of these two words, aura and comes, there is already an idea of how many layers every little gesture can have in my work, and of how much passion I have for linguistic matters.

Sticking with the expressions and words you use most often, one of them is “contemporary.” An adjective you always apply in a positive sense, also associating it with your work.

True. If I think about my work, especially at the start it was very hard to make myself understood: while I was trying to make truly contemporary projects, everybody thought I was working on future scenarios, designing things projected way ahead in time. My goal, on the other hand, has always been to interpret the present and to try to interpret it in the best possible way, producing things for which there is an urgent, timely need, though perhaps not everyone has realized it. Having said this, the idea of the contemporary is very relative, probably my take on it is more extreme (but I would say more realistic) than that of others. So-called contemporary design, in most cases today, seems like the reworking of things of the past, or even a tribute to works from many years ago.

What do you think about traditions and the rhetoric of traditions?

I believe traditions are an important point of reference, but it is also necessary to be selective and critical: some of them no longer have anything to do with our time. In these cases we need to rethink them completely, to update them or ignore them, otherwise they become an obstacle to healthy evolution.

What prompted you many years ago to choose Milan as a city in which to go to school? Today Italy is certainly not the place of the contemporary, but back then maybe it was different…

In 1982 Milan was a reference point. I had studied Interior Design in Barcelona, but I was too young to start working, so I began to look around for a masters program: in the end, the choice came down to a school in India and the Polytechnic School of Design in Milan, where all the post-Bauhaus greats were teaching. Furthermore, Milan was the home of all the great design companies, and the embryonic scene of post-Franco Spain could not be compared to the ferment in Lombardy. Apart from the fact that India was rather far away, I believe Milan was the right choice for me: those were fun years, full of things, of encounters. While in Barcelona the Product Design course was closing (there were more professors than students!), the school in Milan was growing: it was special, perhaps a bit traditionalist, given the fact that my year was the first one without uniforms. But it was also very serious, with a focus on social themes, truly interesting. In the nineties things changed a lot, I don’t know if I would still have chosen Milan at that point.

Martí Guixé, Food Designing, 2010. Corraini Edizioni.

What makes you choose Barcelona and Berlin today? Which of those two cities is the best expression of the contemporary?

The more contemporary is undoubtedly Berlin. After the Olympics Barcelona became a different, unrecognizable city: many people left, I left too. Then I went back, but if you ask me why I live there, today, the only thing I can say is… I’m there by chance! In general, in any case, I prefer staying in motion: when I move it seems like time is passing more quickly, and I like that sensation. Now I would like to add a third home-base city (besides Barcelona and Berlin), so together with my partner we are picking it: it won’t be New York, that’s a city that might have been good back in the thirties, but today I don’t understand the point. It cannot be London, there’s too much focus on money there for my taste. It can’t be in France, because I don’t speak the language. It might be Istanbul, a place with great energy and potential.

Your design is often made to respond to the modes and rhythms of a nomadic life. Could you talk about a particularly good example of this?

Pharma Food, in 1999, a system that nourishes by inhaling, without the need for any utensils, without swallowing anything solid, simply absorbing molecules of vaporized food by breathing, microscopic particles like the dust that is all around us. I developed this experiment with the help of my dietician and a microbiologist. In the air of a room there were vitamins, proteins, carbohydrates, invisible essences that could be breathed by the contemporary nomad who is nourished without the need of any objects, just by crossing the space. The basic idea is to design functions, not forms, to eliminate the weight and the bulk of objects.

But if someone really began to gain nourishment in that way wouldn’t his body change?

Yes, but the evolution has nothing to do with me, at least not when I do design: as I said, I focus on the present, not the future. Though others may think it sounds strange, I consider my projects to be closely connected to today. Though many people see sci-fi and surreal aspects in my work, I also meet a lot of “parklifeists.” This is a term I have invented, based on my project called Park Life, a true Kitchen-City where large works of architecture transform the activity of cooking into a hobby, a sport. My kitchen-city represents a condition that already exists, but people go on overlooking it. If the traditionalists continue to design and live the same old obsolete kitchens, the “parklifeists” are the only ones who are really in tune with the contemporary scene, who would enjoy getting their nutrition by fishing in the vats and cooking on the solar dishes of my park.

You’ve thought about humans who gain nourishment in a big kitchen-city, but you have also imagined them engaged in an activity of reforestation, where they ingest seeds and defecate. Are these just messages, or do you really believe you have found a way of redensifying vegetation?

In general, I imagine things I think will be made, things I think are convenient and feasible. In some cases, as in that of Reforestation Seeds, instead I create a clear, unusual representation that can convey a message. I am aware of the fact that to put Reforestation Seeds into practice you need a particular situation, maybe a vacation in the country, or on an island… I also have fun playing with the need people have today for prepackaged programs, user’s manuals. You know, those throngs of people who do as they’re told and flood cities on “white nights,” or those ladies who wander through art galleries sipping wine and get drunk on the third glass? So, are you hungry for pre-set situations to live by following precise instructions? Well, just buy Reforestation Seeds (they are also on sale at the MoMA!) and follow the instructions! This work is above all a message, there’s some irony, but also a sincere fascination with seeds: the fact that they contain so much information, in spite of being so small, has always impressed me. I believe it is absurd to throw away a seed, so I keep on inventing ways to avoid wasting its natural transmission capacity.

What is your relationship with ecology?

I’m certainly not a fanatic, I try to be ecological in my projects, also for the economic and commercial advantages it brings. An ecological approach leads to savings and guarantees better quality. Today being sustainable makes economic sense, though not everyone has understood that, unfortunately. Having said that, it is also true that I can’t stand moralists, the ones who want to change the world, the true believers, the obsessed. I need to feel free: everything I have done thus far is ecological, it’s true, but who knows, maybe one day I will design weapons… To define myself, sometimes I like to use a German word: frech. I don’t know how to translate it, exactly: maybe cheeky, brash. I mean that I don’t feel ethical in the hyper-coherent, rigid way some other people are, or pretend to be.

You operate by producing ideas and functions instead of forms. But what happens when the time comes to develop a form? Is that really something that doesn’t interest you?

I started doing design with a theory: in a global world, the idea has to be global, the form has to be local. A good example is one of my projects from 1998: a chair made of stacked books, which from country to country was supposed to take on different forms. That was what I thought, but in the end I had to admit that there was a dominant, uniform, undifferentiated global taste at work. The form and its process of realization are not very important to me. I might even regret it, but that’s the way it is. In an ex- and post-industrial society it seems stupid to get involved in solving technical problems: constructing, making things, no longer has value. The value is not in the object, but in what it represents, what its maker wants to say.

OK, but at a certain point the moment comes in which you have to come to terms with form…

Let’s say that more than anything else I find myself interpreting forms, associating them. I am a designer and I could not do otherwise. But literally working on forms bores me, it seems like correcting spelling. I would never go to a factory to follow the production of one of my objects. I really can’t understand how people, in the two-thousands, can still get excited about form and material.

You seem like an excellent analyst of this historical moment, of our society. I have always thought that your design was the result of interdisciplinary reflection, with a number of connections to anthropology. Are you interested in that subject?

I have read anthropology, but I couldn’t tell you the name of a book or a theorist that influenced me, a part from Octavi Rofes, an anthropologist who is also a dear friend of mine. He is one of the most acute interpreters of my work that, he tells me, he finds it interesting for his studies. He says, for example, that Spamt Factory, the performance in which I and a group of friends prepared “contemporary tapas” during an opening at the H2O gallery in Barcelona, was a good representation of the transformations that were impacting the world of design. In his interpretation, considering the decline of the industrial society and the spread of globalization, we designers will have to invent a new job for ourselves. Exactly like the characters in the film The Full Monty! Instead of designing chairs, we will have to become the players in an improbable, captivating spectacle…

Who are the clients and fans of Martí Guixé?

They are bourgeois people full of contradictions, bourgeois people who don’t accept the fact that that is what they are. They have money but they don’t like environments for the rich. They could afford expensive restaurants but they look for original, casual places that have character. They’re like me: I too could afford to eat in very expensive restaurants, but I prefer to eat in a well-conceived fast food place, with quality food prepared and served in a contemporary, functional way. I have a good example to explain who buys my stuff: some years ago, for Danese, I made the Xarxa seat, composed of five excellent cushions that could be assembled in different ways. The seat cost one thousand five hundred euros. I remember someone said: with one thousand five hundred euros at Ikea I can buy a nice four-seater divan! Those who buy Xarxa, on the other hand, are buying a new seating concept: they are not looking for a big divan, they choose an original and rather radical idea instead of a conventional object. Of course you have to have money to spend one thousand five hundred euros on five cushions.

What do you think about democratic design?

At the start, but just at the start, I believed in it. Then I understood that it is not my thing: it forces you to become more commercial, simpler, and instead I like design that is a bit more complicated, full of layers and interpretations. I like projects that are usually understood and appreciated only in certain social contexts, it would be hypocritical to claim otherwise. My super-sophisticated and contemporary snacks would not be successful anywhere. I believe that the experiences of the big discount chains (Ikea, but also Muji), in the end, are really negative: they produce billions of cheap objects, all exactly the same, things that don’t last, substitutes.

Once, however, you wrote on a plastic chair: Stop discrimination of cheap furniture. Is there a contradiction here?

No, anything but. Once again, the project has layers of interpretation that is not immediate or universal. The chair was shown in Holland, and “cheap” in Dutch corresponds to gut gekauft that literally means “well purchased.” So the meaning was: don’t discriminate against a chair that has been well bought. This work, then, is a statement to defend a plastic monoblock, which I consider a brilliant object, above all if you think of it as a sort of disposable thing, something that can break or easily get lost. If someone steals a monoblock from your garden, or if the winter climate destroys it, you can replace it very easily. The basic idea is very different from the furniture that is worth nothing and is sold to furnish entire homes.

Martí Guixé, Spamt, 1997. Photo: Imagekontainer/Knölke.

Your design often has a playful character, but it is a subtle game, aimed mostly at adults. Have you thought about doing projects for children?

Yes, there is one in particular that I really like; I’m working on it for Magis, in the Me Too children’s collection. It will be called My Zoo, a series of gigantic animals made of cardboard, all white. Five of them are already in production, but I’ve designed twelve. The thing that convinces me about them is that the children will be able to sit on them and color them, but also go inside them. The whale will be eight meters long, enormous! It’s the one I like best, the one with the most meanings, connected to fables, the tradition, psychology. Just think how much fun it would be to enter the belly of a whale!

We said that your work is multi-layered, dense with overlapping, conscious meanings, in a dialogue with different disciplines. What, on the other hand, is the role of chance? In your design, but also in your life.

I love chance. Some of my projects, like the interiors of the Desigual shops, were made by seeking the complicity of chance: I organized parties inside empty spaces, and during the parties anyone could color or draw on the walls, whatever they wanted, in a rather wild way, helped by the atmosphere of the party. The resulting environments were truly authentic, nothing like the fake-spontaneous graphics that are all the rage in clothing stores. In my life, too, chance plays a central role: it was purely by chance that I staged one of the first performances in the field of design, the one we mentioned earlier. It was 1997 and I had an exhibition at the H2O Gallery in Barcelona to present my Spamt, substantially techno-tapas, a contemporary reinterpretation of traditional Spanish snacks. Specifically, Spamt transforms the classic bread-tomato-oil-salt combination into a snack that is entirely contained by a small tomato, making it very easy to eat. Well, to present that I had decided to just show photographs. The gallerist did not agree, and the local TV station was disappointed about the fact that there were no objects in a design exhibition. So the gallerist convinced me: since I didn’t want to exhibit things, at least I would have to act out the preparation of the Spamt snacks at the opening. Because I don’t like to work with my hands, I got four friends involved: a Japanese guy to cut the tomatoes (precise!), a Swede who emptied them, a Frenchman to fill them with bread, and an Italian to season them with oil and salt. I was the quality control guy, to make sure everything went smoothly… it was fun, a success that happened by chance, that indicated the path to a new way of doing design, as we were saying before.

Today “performed” design is very much the vogue, an unstoppable trend: I’m thinking about Design Miami, Craft Punk and many other such events. What do you think?

These things don’t interest me at all, they have little to do with the preparation of my Spamt snacks, and they even make me a little depressed. It’s like going to the zoo, lots of cages, with these designers who show you how they make their chair. I repeat, in an era in which only ideas count, in which objects take form in Chinese factories without any attention being paid to the process, staging the work of a craftsman on a piece of contemporary design seems completely out of place, and somewhat pathetic.

What about the artists who do performances with food? Rirkrit Tiravanija, for example?

Once in Berlin I went to an event: there was Thomas Demand who showed some of his films, while Rirkrit Tiravanija cooked up a storm, for thirty or forty people… I hate working with my hands, and I don’t understand the appeal, I don’t see the fun in cooking for all those people, doing all that work. It is easier for me to understand the work of someone like Antoni Miralda, for example. I’ve always been intrigued by his artistic experimentation with foods: he worked in an era when there was the boom of colorings, and the way he used them in his works demonstrated an avant-garde focus. Of course, his work has nothing to do with my design: he makes art, I design saleable concepts.

And your relationship with the marketing side, the sale of your projects? I tried to interact with the site buyguixe.com, though now it seems to be closed. What was it?

Just an experiment, which says a lot about my great passion for computer languages and new technologies. I developed it myself, many years ago. At the time I often said: I speak six languages: Spanish, Catalan, Italian, English, German and HTML! I was truly obsessed by the novelty of the Web, at the beginning I went crazy because I knew it was there but no one could explain to you how to get access, how to use it. I remember that for three months I chased a friend of mine who was a programmer, to get some explanations about it. Buyguixe.com was a custom site to show my projects, which could be purchased online, or at least that was part of the intent! But the companies were against a formula that combined different brands, and then people said there were lots of problems involving payments. In short, it never really worked, commercially.

Martí Guixé, Xarxa, 2008. Design for Danese Milano. Photo: Miro Zagnoli.

You seem to have very good relationships with companies that are very strong commercially, like Camper and Alessi, that have had faith in you and even go along with your more poetic, visionary projects.

I often propose very extreme things, that I am able to complete only partially, though in general I must say that certain relationships function very well. I am very pleased, for example, about the project for the new Alessi space in Milan, on Via Manzoni. They were enthusiastic about my idea, even though it was absolutely unconventional, and to tell the truth a bit disorienting. While the French store I made for them mixes red, white and blue neon, to garb it in a strange pink light, in Milan we went even further with the lighting. Usually in shops only a few lighting mixes are permitted, but with Alessi we could be daring.

Before you said you were obsessed with computer languages. I might add: you love instructions…

As a kid I loved comics. Mariscal, as a comic artist, was my idol. But instead of drawing comics, I found myself designing instructions, the users’ manuals for a company that produced optical lenses. It was one of my first jobs, in 1988. My task was to invent storyboards for these manuals, and that is where my passion began. At first I drew clear, precise figures, but then I started to make sketches, removing more and more. Now I like to doodle: essential figures, but eloquent. The more succinct and quick the drawings, the more meaningful and effective they are as instructions.

How did instructions get to be so essential in your design?

It still has to do with my conviction that forms are no longer important today. I really believe that you can produce locally, following general, global instructions. Once I got very angry because during an urban event in Valencia I wanted my design object for Droog to simply be a set of instructions. For example: paint that wall white, make a flyer that indicates the most interesting bars in the center of town, etc. Droog did not accept the project, they said it was too abstract… My idea was replaced by some containers, in which Valencians could do some sort of creative activities, melting in the heat. Outside it was forty degrees in the shade, so inside it was unbelievably hot. The creator of this piece was a Nordic designer. I am also reminded of another similar episode, I think it was during a conference of Doctors Without Borders. Some doctors working in South America pointed out the uselessness and waste of some very expensive masks – by a Spanish designer, produced in Finland – to protect communities struck by earthquakes against the dust and fumes caused by the quake. According to the doctors, all you needed was a piece of wet cloth, placed over the mouth and nose. In certain circumstances it is fundamental to make the best possible use of the available resources, by following instructions.

You have very clear ideas about what doesn’t make sense in design. What do you teach to people who turn to you to learn about it?

First, I try to transmit the need to be critical: nothing should ever be taken for granted, we should never rely on previous ideas or knowledge, never offer superficial responses. I’ll give you an example. Some time ago I conducted a workshop at the Polytechnic School of Design: we had to develop some design projects starting with three typical products from the Lombardy tradition: panettone and two types of cheese. I introduced the workshop by saying that panettone could become a sandwich with the two cheeses inside it, between its layers. The Italians immediately turned up their noses: bleah, disgusting, impossible. Well, I advise against this type of attitude: if you say it is impossible, you have to tell me why! Or, before saying that it is not a good idea, consult a taste expert: he might find a way to combine even very different flavors, correcting the acidity with one ingredient or another. First experiment, go as far as you can, there will always be plenty of time to say bleah… and what if you find out you were wrong?

Martí Guixé, Park Life #003 Burn-Me Piece, 2008. Photo: Imagekontainer/Knölke.

Martí Guixé, Camper Shop, Miami, 2010. Photo: Imagekontainer/Knölke.

Martí Guixé, Xarxa, 2008. Design for Danese Milano. Photo: Miro Zagnoli.