17 April 2018

Giulio Iacchetti is someone who designs reflections in the shape of objects. His work is that of a committed designer, one who takes a stand. He follows the tradition of the great Italian masters of the discipline. His mode of design, however, is much more worldly wise: the messages he sends are often political, but without the ideological imprint of an Enzo Mari; his forms are always the result of a line of reasoning, just as they were for Castiglioni, but with a freedom of expression that the latter did not allow himself. He is one of the designers who best represent the passage from the old to the new generation, having won two Compassi d’Oro and collaborated with the most important companies working in the field of contemporary design: Foscarini, Alessi, Artemide, Guzzini, Sambonet, Danese Milan, Globo, Fontana Arte and Moleskine. I met up with Giulio, who had already granted Klat an interview back in 2010, at the Triennale for a coffee and a chat.

How did you come to design, what route did you take to get there?

I came to it later on, not straightaway, taking my time. I think that at the end of the eighties I didn’t even know what “design” meant. For me it was a meaningless word. Afterward, I simply became aware of one thing: something I knew how to do could become a job. I made things by hand, and often had to find solutions dictated by my precarious economic situation, building myself an amplifier, an electric bass or instruments that I would then sell so I could buy other things. My father had an incredible ability to make objects that solved problems. He was very good at it, he could make almost anything. But his attitude was that of an engineer. He assigned no aesthetic value to things. For him beauty seemed almost to be something superfluous, almost an obstacle to finding a solution. I’ve always tried to emulate his skill as a constructor and problem-solver but, unlike him, I’ve never regarded aesthetics as something negative.

So it was your father who, unwittingly, made you a designer, rather than a school.

When I finished high school, since I was good at technical drawing, I enrolled to study architecture. I hated that course from the outset, it was an awful experience. What saved me was being called up for military service, which have me the chance to think about my “no” and to leave university. Later I enrolled in a school of design promoted by the Region of Lombardy. It was quite an unlikely thing, but turned out to be important because it was there that I realized I could make a living out of what I did. So I started to propose my designs to companies.

Olmo Lamp, Artemide, 2015. Example of a project that stemmed from an intuition for a lamp, and that then went in various directions before turning into a highly complex lighting system (“The project is never a straight road,” Giulio Iacchetti).

At the time you were in Cremona, how did you arrive in Milan?

[Smiles] In the end all roads of design lead to Milan.

You are one of the few designers who describe their projects as processes full of mistakes, corrections, second thoughts and changes of mind. This is unusual, because generally we are presented with a romantic idea of the design process: the designer makes a sketch of his idea and everything follows in a straightforward manner until it has been realized. It seems that you wish to stress the technical difficulties of a craft rather than the expressive intuition of an artist.

I’ll ask you a rhetorical question: would you ever ask an engineer to talk about the romantic attitude that inspired his design of a bridge or a beam? Someone might respond: “but he’s a technician.” Well, I say that designers are technicians. By this I do not mean to deny the existence of poetry understood in the sense of an immaterial value able to bring something special into our lives. Poetry exists, but you don’t make poetry with a poetic attitude. A question I’m often asked is: “where do you get your inspiration?” Faced with this question, I used to invent answers, partly because I found it hard not to humor my questioner or my public. But the truth is that the designer is a professional in just the same way an engineer is. Unfortunately, our work is often associated with something romantic, intuitive, artistic, but it is essentially a technical activity. Sometimes they call me a creative, and I don’t like it. Creative is a terrible word.

Magneto lamp, Foscarini, 2012. The core of the design is a magnetic sphere that makes it possible to direct the light wherever you wish.

It’s technical work that has changed a great deal over time. A studio of design today has many more roles than in the past.

Today we have to take responsibility for passages in design that companies are often unable to handle with their technical offices. For example, it has become fundamental to have professionals in the studio with the skills needed to make effective use of CAD and 3D programs. Communication is another area of expertise has now passed in part to the studios. This is not because the studios have any desire to exercise control over everything, but because they have realized that communication is part of design, and so you can’t delegate it. When the social media began to make an impact, companies showed a great deal of suspicion about what designers were doing, how they communicated, and in some cases the designer was not authorized to say certain things as everything had to be kept under the strict control of the companies. Now, though, they are actually encouraging designers to publicize their projects, as they have understood that in this way the act of communication becomes more effective and synergic, reaching different sections of the public. As far as I’m concerned, and in more general terms, I want to be able to keep control of what we are doing. For example, I’ve never considered the possibility of hiring a lot of people to design for me. I enjoy the process of design and want to go on supervising it directly at every stage with a few trusted assistants.

With Internoitaliano you’ve created a brand, you’ve organized a network of artisans for production and you’ve put together a collection of objects. With Eureka Coop you’ve assembled a team of twenty designers, you’ve given them a brief and you’ve had them work on projects for the large-scale retail trade. From a designer of products you have turned into a designer of processes.

That’s a good definition you’ve given it, “designer of processes.” Let’s put it like this, I could have designed all the objects for the Coop by myself. They certainly wouldn’t have turned out so well, but I could have done it, perhaps even with less effort: bringing together twenty designers with their own times, their different briefs, keeping an eye on developments, following their progress, the difficulty of communicating with everyone, none of this has been easy. It would have been less trouble to do everything myself, but would the same energy of design have gone into the operation? Absolutely not. I think it was the group that gave value and meaning to the initiative. As you put it, it was the “design of a process.” The beauty of design is that it has many different nuances and is never based on a single vision. And then this idea of “designing processes” is a specifically Italian phenomenon. Only in our country do designers join forces, band together in order to have more than one view of a single theme. I could list at least thirty of these experiences in Italy over the last twenty years. In other countries they practically don’t exist.

Erba, Mira and Pila flowerpots, Internoitaliano, 2012.

Admit it, you really like the Italian way of doing design.

Yes absolutely, you won’t find the attitude that Italian designers have to their profession anywhere else in the world. I find that my colleagues are really aware of what is happening in the field of design and art, and very well-informed about what is going on around them. Italy truly is the cradle of design culture. Because at its base there is a strong measure of humanism, of careful thinking, that comes before the capacity to come up with good designs.

What do you think of the phenomenon of self-production?

Personally, I belong to the school of thought that sees self-production as an exercise in combatting frustration: “since my company doesn’t understand me, I’ll go somewhere else to produce my idea, at my own expense.” In my view, though, the question is often a quite different one and I’d put it like this: since you’re not a good designer, the company rightly tells you no, but you don’t accept this and so you go and produce your own pieces, saying: “you see that I was right?” I’d put it bluntly: it’s a failure, it’s like fixing the match. You can’t score a goal? Then pay off the ref. It’s something else to try making shots on goal; maybe they don’t count toward your standing in the league, but they do help you learn. In that case, I think self-production makes sense. In my career, I’ve had a go at self-production several times, not just with Internoitaliano. I remember founding a brand with Matteo Ragni. It was called Sinequanon and we made articles out of photoengraved sheet metal. We wanted to carry out an experiment in which we could have total control over the product: from the conception of the brand to the design and the marketing. The result was that the brand and design worked, while from the viewpoint of the market it was a complete failure: we got the positioning, costs and distribution wrong. We lost money. The operation didn’t hold up economically. Self-production makes no sense when the designer produces his own pieces in order to sell them, but it does when it’s an opportunity to experiment. If it then turns out to suit the tastes of people and the market all the better, but that is not the aim, or at least it ought not to be.

Gisa chair, Bross, 2016.

Your design is decidedly anti-elitist. You try to make yourself understood—and perhaps bought as well—by large numbers of people. Yet there is a design whose principal referents are insiders.

I don’t like that kind of design, I have a different mission. I think that all objects have to pass the scrutiny of my mother’s eyes [he picks up a large pen]. Sometimes I show her this and I say: “mom, what does this look like?” And she answers: “to me it looks like a machine gun.” And she’s right, because it doesn’t look like a pen. Making a chair that has the appearance of a chair doesn’t mean catering to my mother’s taste; rather it serves to help people to understand design, to appreciate it, and thus to foster a process of functional and aesthetic improvement. I don’t believe that design should indulge people’s taste, I think its job is to improve their taste. This can only happen through a design that tries to make itself understood, that does not exclude the general public. Look at the pictures in the magazines: where do you find furniture like that in real life? And the other way round, where can we see “design” in people’s homes? Like everyone I go to the homes of ordinary people and I never see those things there, that style. It’s not the designer’s job to create dreams or illusions, but to build bridges with everyday life. People need bridges, otherwise they would fall in the water and might drown.

Design in the service of people.

Exactly. People don’t buy many designer pieces not only because they cost a lot of money, but above all because they don’t understand them. When people are saying “that thing there is completely incomprehensible” we have failed. Many of the things that are shown at the Salone and the Fuorisalone are only really understood by insiders. But the world of design doesn’t end there. Just think of mass phenomena like IKEA or Flying Tiger—on a completely different scale. I, as a designer, want to look in that direction too. Working for the Coop was also an attempt to hold a dialogue with the immense universe of the large-scale retail trade. Even today, the creations of designers can only be found in a very few homes, those of a few highly cultivated people: lawyers, doctors, architects, professionals. I’m not happy about this, because it means that designers have not been able to communicate effectively with a broader swathe of the public.

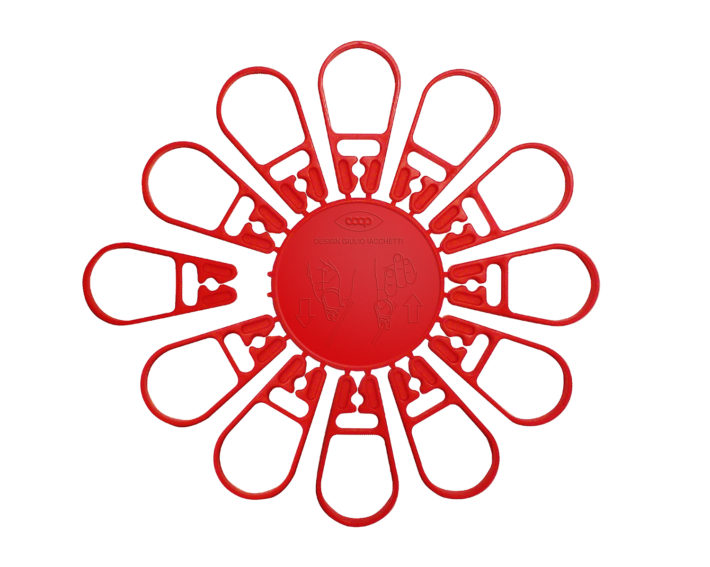

Clothespin, Coop, 2008.

Your work is heavily influenced by the masters of design: Castiglioni, Sottsass, Mari, Mangiarotti, Aldo Rossi. Have you ever had any contact with them?

I have to say, sincerely, that I’ve never been interested in establishing a relationship with the designers themselves. What does interest me is their designs. My studio is full of their designs. By now almost all of them are dead, but their works go on telling me many things, you just have to know how to listen to them. I have a plethora of masters right next to me, in the form of their objects.

As well as designing industrial products, you carry out experiments—or perhaps they are reflections—on design. I find your collection of coltelli inutili, “unnecessary knives,” interesting, for example.

The purpose of that work was to reflect critically and ironically on the fact that there is a special knife for every kind of food. There are all sorts of knives: for cheese, fish, fruit, meat, truffles, etc. Whereas when it comes down to it you can cut practically anything with the same knife. I’ve always found this sophistication a bit of a joke. I don’t like all the trappings that keep us away from that very beautiful and atavistic thing we call “hunger.” I can’t bear the artificial world of food design, I find such a cult of the superfluous intolerable. So I worked on unnecessariness, a fundamental concept that anyone in our profession needs to look at.

![Coltelli Inutili [Unnecessary Knives], Coltellerie Berti, 2008.](https://www.klatmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/07A_Coltelli_Inutili-710x473.jpg)

Coltelli Inutili [Unnecessary Knives], Coltellerie Berti, 2008.

Keeping to the subject of unnecessariness, you’ve been working for some time on the Ossi. How far have you got?

The Ossi/Ossimori [“Bones/Oxymora”] project will be presented this very week in Milan, for the Fuorisalone, at the Galleria Luisa Delle Piane. It will be a collection of 11 bones carved out of wood mostly by Emmanuel Zonta and to a small extent by me. They are all bones of impossible animals.

Why bones?

I’m interested in the formal quality of bones. Anything can be designed, except a bone. The bone is a product of nature and evolution: it is light, sculptural, strong. I’d like to reaffirm the plastic value of things. Bruno Munari said that paleontologists are extraordinary fantasists, because they are able to reconstruct the entire skeleton of an ancient dinosaur from a single bone and this is something I have always found fascinating.

![Ossi/Ossimori [Bones/Oxymora], Giulio Iacchetti and Emmanuel Zonta, 2018.](https://www.klatmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/07B_Collezione_Ossi_2018-710x533.jpg)

Ossi/Ossimori [Bones/Oxymora], Giulio Iacchetti and Emmanuel Zonta, 2018.

You mentioned the Salone of the Mobile. Let’s talk about it.

There are many different opinions and analyses of the Salone, some of them right and some wrong. Before it all starts, there’s always a great fuss about what are going to be the most interesting new things to see, the coolest events, the designs not to be missed and so on. Then you summon all your patience, try to see as many things as possible, but it’s not enough, because there will always be an influencer, “a Bertoncelli or a priest to shoot the crap”—to quote from Francesco Guccini’s L’avvelenata—on the exhibitions that only he has seen. In spite of everything, I’m always moved by Milan Design Week. I see the immense efforts of so many people who are driven here by the idea of being able to speak their mind, perhaps not in the most authentic way, and certainly with room for improvement, but displaying great enthusiasm and energy. These untidy and open-handed impulses are the things I like most. I’m less fond of the big installations of the super brands in which starchitects are often involved.

Fabbrica del Vapore humidifier, Il Coccio, 2010.

Who do you think are the most interesting designers at the moment? The ones you follow most closely.

In my view there are two kinds of designer who approach design in two different ways: there are the ones with a more aestheticizing vision of the work, with an attention to detail that verges on affectedness. And I’m not very interested in these designers.

Instead there are those who choose to go down more difficult roads, where the idea is central and innovation and technology are integrated into projects that are never easy. It is a wholly Italian current of design that in my view started out from our great practitioners of the profession. I look to them with the maximum of interest. I am talking about Denis Santachiara, Marco Ferreri, Alberto Meda, Paolo Ulian and Riccardo Blumer. But I’m also very interested in Odo Fioravanti, some of the designs of Sovrappensiero, the Martinelli Venezia studio, Alessandro Gnocchi and Lanzavecchia + Wai, to mention just a few.

But you are critical with regard to the promotion of “young designers.”

I don’t like the idea that professionals can be divided up on the basis of their age, and this is particularly true for designers. Tommaso Labranca wrote: “I advise anyone who has been defined a new author to take legal action.” Someone who is presented as a promising youngster is in fact doomed to rapid obsolescence, hurriedly scrapped to make room for a new wave of cooler youngsters to be thrown into the meat grinder of advertising. Let’s at least try to get rid of this absurd way of doing things and instead place value only on the efficacy of the ideas and the projects. If the design is good, the age of the person who has produced it matters little. For me it’s only the design that counts.

Well, with that I think we’ve finished. Thank you Giulio.

Thank you, although I don’t think I’ve told you everything yet. Are you sure you have to go already?

Ginkgo handle, Dnd, 2017.

Roller pen, Moleskine, 2011.

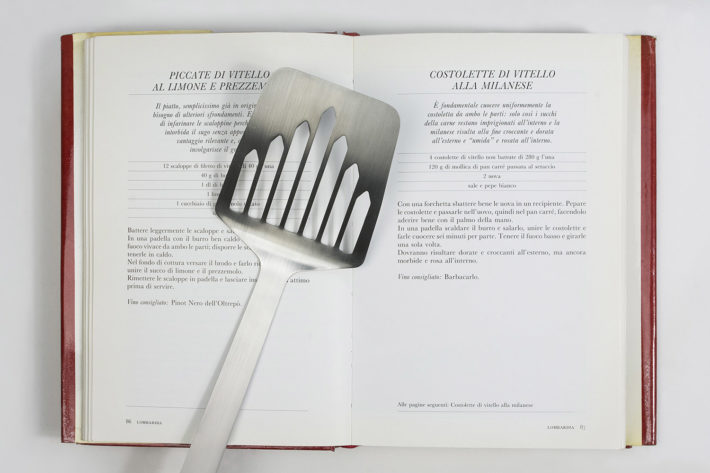

Spatula for Radetzky cutlet, Souvenir d’Italia collection, Il Coccio, 2017.

Radica Chic pipe, Savinelli, 2015.

Tartineur spreader spoon, Alessi, 2017. Solves the problem of finding a support.

Affi stool, Internoitaliano, 2012.

Moscardino spork, Pandora Design, Giulio Iacchetti and Matteo Ragni, 2000. Winner of the 19th Compasso d’Oro in 2001.