8 June 2018

Chiara Alessi is a critic who likes to reflect on the cultural aspects of design, and with this book, Le caffettiere dei miei bisnonni. La fine delle icone nel design italiano [My Great Grandparents’ Coffee Maker: The End of Icons in Italian Design], seems to be telling us that it can be a very subtle tool of social analysis: sometimes it is enough to take a look at how we are utilizing or how we perceive objects of everyday use in order to understand who we are. In this case, the starting point is a news report: that of the meeting which took place in Rome, in January 2016, between the prime minister of Italy at the time, Matteo Renzi, and the CEO of Apple, Tim Cook. On that occasion Renzi gave Cook a contemporary version of the Bialetti moka pot, as an example of an icon of Italian design. The moka pot was devised by Alfonso Bialetti in 1933 and perfected over time until it became in the fifties, thanks to the intuitions of his son Renato, the extraordinarily successful product we are all familiar with (NB: a contribution to this success was made by the little man with the mustache, invented by the cartoonist Paul Campani and portraying Renato Bialetti, which became an icon in its own right in the years of the TV advertising show called Carosello).

Valentine typewriter designed by Ettore Sottsass for Olivetti, 1969.

The author stresses one fact above all: the Bialetti moka pot has managed to retain all of its iconic character even in its contemporary guise, that of the one Renzi gave to Tim Cook, despite its differences from the original version: the handle has been given a more rounded form and raised; the valve, initially made of brass, is now made of steel; the grooves in the knob were not there originally; and the logo that was once on the base is set higher up today. Modifications that reflect changes in taste, technology and manufacturing processes. The second, and more crucial, piece of evidence regards the fact that the object chosen as a symbol of Italian creativity has a history going back over eighty years, to another age. Thus the anecdote provides the opportunity to ask a fundamental question: why is Italian design, today, unable to come up with new icons? How is it that we no longer see the emergence in our country of everyday and timeless products like the moka pot, so radical in their uniqueness and recognizability that they are capable of bringing about anthropological changes in people’s actions and rituals?

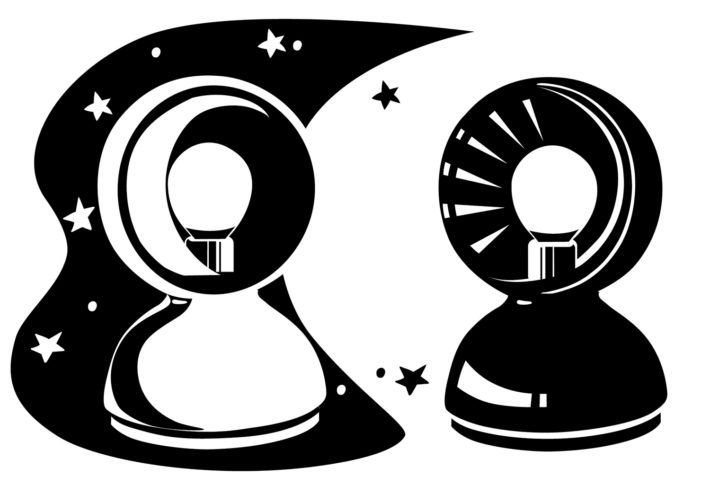

Eclisse lamp designed by Vico Magistretti for Artemide, 1967.

“The most immediate answer,” writes Alessi, “and yet the incorrect one, is to put it down to the factor of distance in time: the idea that we are too close historically to the material production that surrounds us to be able to perceive its iconic character.” It is true, time “helps to confirm the iconicity of some objects and to strengthen it,” but “a specific historical distance” is not needed “to identify icons.” The fact “that the iPhone is an iconic object of design is something that can be said without much doubt and without much time having passed since its appearance on the market.” The correct answer to the question, suggests Alessi, is that “not all times are favorable for the birth of icons.” Her general thesis—and the argument does not hold for Italy alone—is that we are so deeply embedded in our own time that we are unable to distance ourselves from it, incapable of achieving the detachment needed to create a perspective from which to unite present, past and future. And in particular, in the passage from a culture of commodities to the digital one, Italian design has not been able to replace the great icons linked to traditional types of object (lamps, chairs, radios) “with new pocket icons, for the drawer or the desktop.”

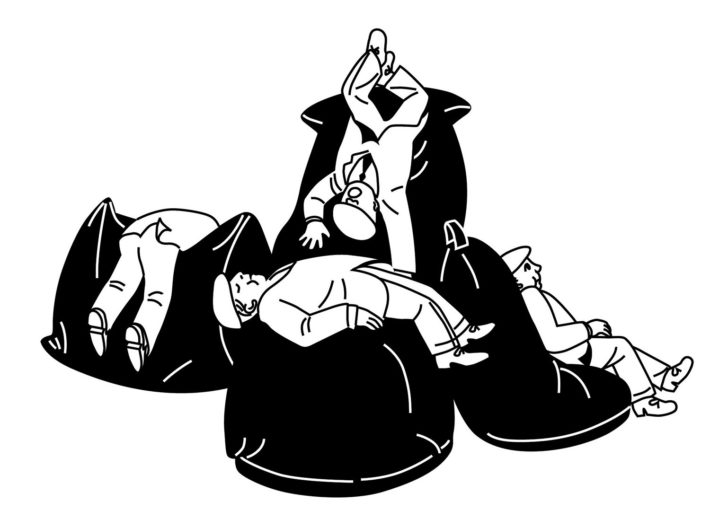

Sacco armchair designed by Gatti, Paolini and Teodoro for Zanotta, 1969.

Today it is the global iconic brands, from Apple to Netflix, that meet the desires and needs of millions of consumers, but with a limitation: their products seem anchored to an eternal present, reflecting, pursuing and anticipating it, without fixing a form that can stand the test of time. So that, while the “design of the past is still alive in our present, our present seems to have difficulty in creating a credible and lasting image to hand down to the future.” The society that has emerged since the beginning of the new century, already examined in another of the author’s books Dopo gli anni zero, is profoundly different from that of the last one. There is something kitsch about the age in which we live, and not in the sense of bad taste. It’s a question of emotivity: we look for strongly aestheticizing experiences, products that are able to provide immediate gratification (“In the realm of kitsch, the dictatorship of the heart reigns supreme,” wrote Milan Kundera). According to Chiara Alessi, “it’s not that objects no longer catch our imagination. Far from it. The present without a future is a time of perennial desires and satisfaction of desires, but without the absorption required to turn those instant desires or needs into a more complex and mature feeling. More than ever, what works today are those “things” that do not necessarily have to function for a long time, but are able to stir strong, and immediate, emotions.”

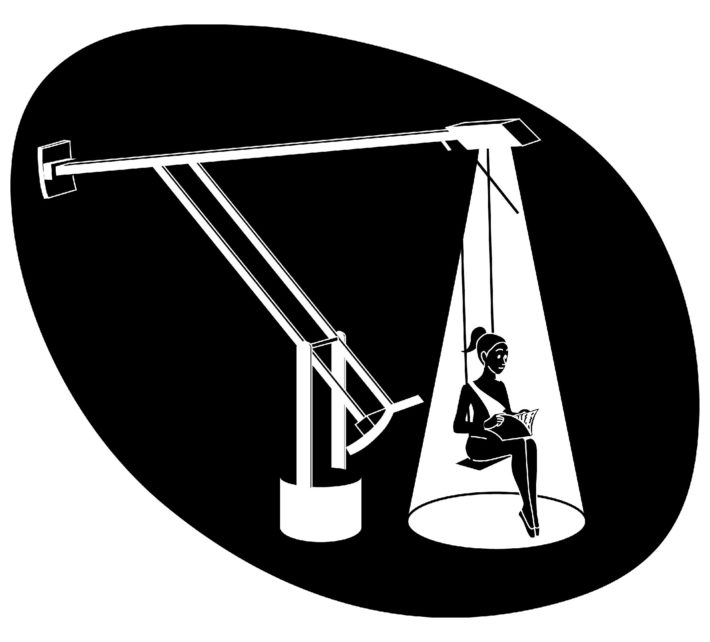

Arco lamp designed by the Castiglioni brothers for Flos, 1962.

This new conception of objects cannot help but bring about significant changes in both the world of production and the way that design is described and communicated. It is very likely that new museums of design or new books on its history will have to deal with objects that have had short lifetimes and with specific periods. Perhaps the very idea of the “museum” as we have always conceived it, as a container of representative products, will have to be questioned. Chiara’s great grandparents have names to conjure with: they were Alfonso Bialetti and Giovanni Alessi, industrialists who came up with enduring archetypes. The new iconic objects, like the iPhone, are conceived with a view to their periodical redesign and replacement by new models, ever more irresistible, powerful and innovative. Maybe the time has come to reconsider the meaning of the iconicity on which much of the history of design is founded.

Egg chair designed by Arne Jacobsen for Fritz Hansen, 1958.

The iPod, first marketed by Apple in 2001.

Tolomeo lamp designed by Michele De Lucchi for Artemide, 1987.

Tizio lamp designed by Richard Sapper for Artemide, 1972.

9090 coffee maker designed by Richard Sapper for Alessi, 1979.

The moka pot, conceived by Alfonso Bialetti in 1933.

Moscardino spork designed by Giulio Iacchetti and Matteo Ragni for Pandora Design, 2000.

Proust armchair designed by Alessandro Mendini, 1978.

Anna G. corkscrew designed by Alessandro Mendini for Alessi, 1994.

The Fiat 500 designed by Dante Giacosa in 1957.

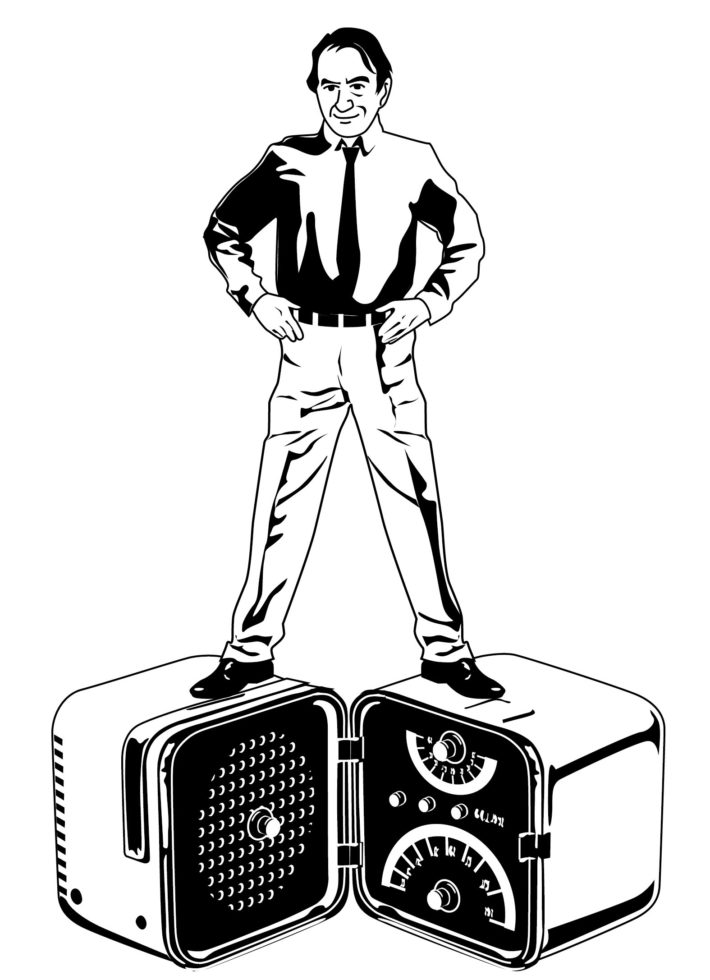

Brionvega TS502 radio, commonly known as the Cube, designed by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper in 1963.

Carlton Bookcase designed by Ettore Sottsass for Memphis, 1981.

Rompitratta light switch designed by Pier Giacomo and Achille Castiglioni for VLM, 1968.

Grillo telephone designed by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper for Siemens, 1965.

Falkland lamp designed by Bruno Munari for Danese, 1964.

Braun electric razor, designed by Dieter Rams in 1958.

Juicy Salif citrus squeezer designed by Philippe Stark for Alessi, 1990.