20 June 2014

In the panorama of Italian design, the companies specializing in lighting have always distinguished themselves by the quality of their products and a commercial success that extends far beyond the borders of the country. Among these, Foscarini has only been in existence for a relatively short time, but has quickly earned itself a reputation both for the variety of its catalogue and for its relationship with its designers (who are always first class) and the philosophy it applies to the product (highly original and contemporary). We went to see Alessandro Vecchiato, who along with Carlo Urbinati has held the reins of the company since 1988, to find out what lies behind such a distinctive story.

Producing light means illuminating in a very concrete sense, but also in broader and more emotional one. It is no coincidence that one of the recurrent messages of your publicity is: “The first material we work on is emotion.” How do you see light?

For us light is emotion. We sell light, which means illuminating in the right way, and conveying emotions to someone in a particular setting. Our objects look well-constructed even when they are turned off, but they have to be even more interesting, beautiful and emotive when they are lit, enhancing the room they are illuminating. You can have a beautiful kitchen, but the wrong lamp is capable of ruining it for you completely. For this reason we work on the exterior, on the “dress” that is visible even when the lamp is turned off, but aim to amplify the effect through light. By making sure that the bulb (whether it’s LED or some other source) doesn’t dazzle, that the shadows cast are beautiful and not disturbing: this is our objective. We have achieved it when someone sees one of our lamps and says: what a fine lamp! And then turns it on and exclaims: what a fine effect!

The Milan Furniture Show ended two months ago. What does it represent for you?

Euroluce remains the most important event in the sector and takes place every two years. Despite this year not being held a Euroluce year, we presented the definitive version of the designs we had previewed last year: a lamp by Ferruccio Laviani (Tuareg), one by Jean Marie Massaud (Lightwing) and one by Ludovica and Roberto Palomba (Rituals), which is getting excellent feedback. And then we have launched something completely new: a highly distinctive LED hanging lamp by Vicente Garcia Jimenez and Cinzia Cumini (Spokes) in which the light source is very well-concealed and the design is inspired by the spokes of a bicycle, with a wire that is at once luminous and transparent and replicated around eighty times.

Tuareg, design by Ferruccio Laviani for Foscarini, 2014.

What do you think about the search for novelty at all costs that characterizes these events? The multiplication in the number of fairs is requiring a quantity of presentations that is not always compatible with the time needed to prepare a design.

It’s undeniable that there is pressure to present new things that may then never go into production. But at Foscarini we take another approach: when Euroluce is on we try to address an international public, and we do it by proposing a range of new products that will cover the next two years. But when there’s no Euroluce, we generally limit ourselves to presenting products that confirm what was announced the previous year.

How long does it take on average for a design to go from concept to product?

No less than a year, but it can take two, it depends on the design. This is because we’re not doing fashion, we’re not working on a seasonal cycle. The design product is not a dress or a sweater that may be changed every six months. The lamp is an object that on average is purchased two or three times over the course of a lifetime, whereas people buy a new sweater every year. So it is inevitable that we take this perspective in our work: the success of one of our products is measured in part by how long it lasts.

Foscarini’s public is an international one. In your proposals do you take geographical differences in tastes and markets into account or do you rely entirely on versatility, even at the cost of modifying a typically Italian mode of production?

The globalization of markets is tending to do away with geographical peculiarities. But what we want and have to sell is Italian design. This means coming up with a product that is a concentrate of all our capacities and skills: from workmanship to beauty of line. In this we Italians are still the best, even though we are losing ground.

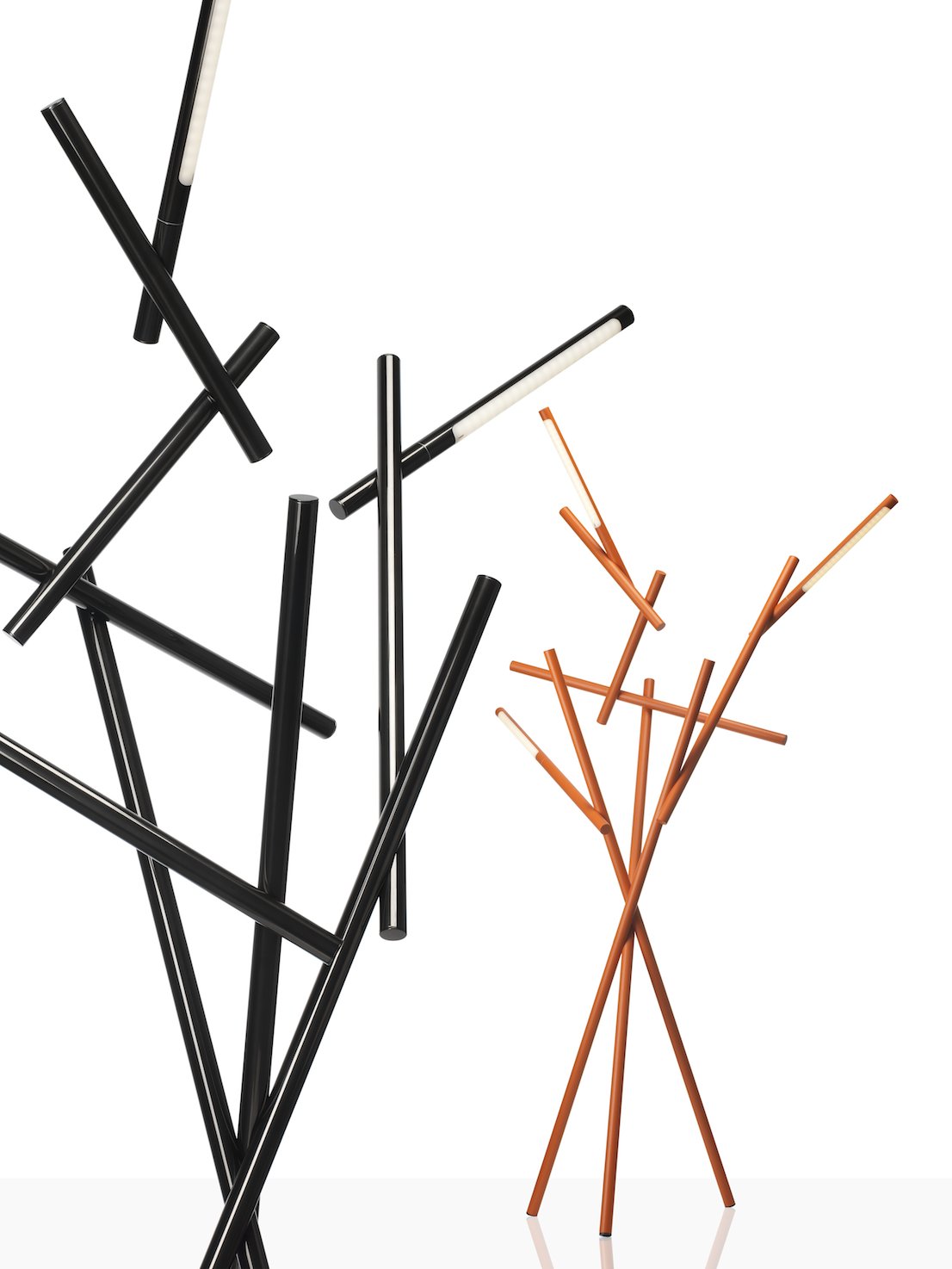

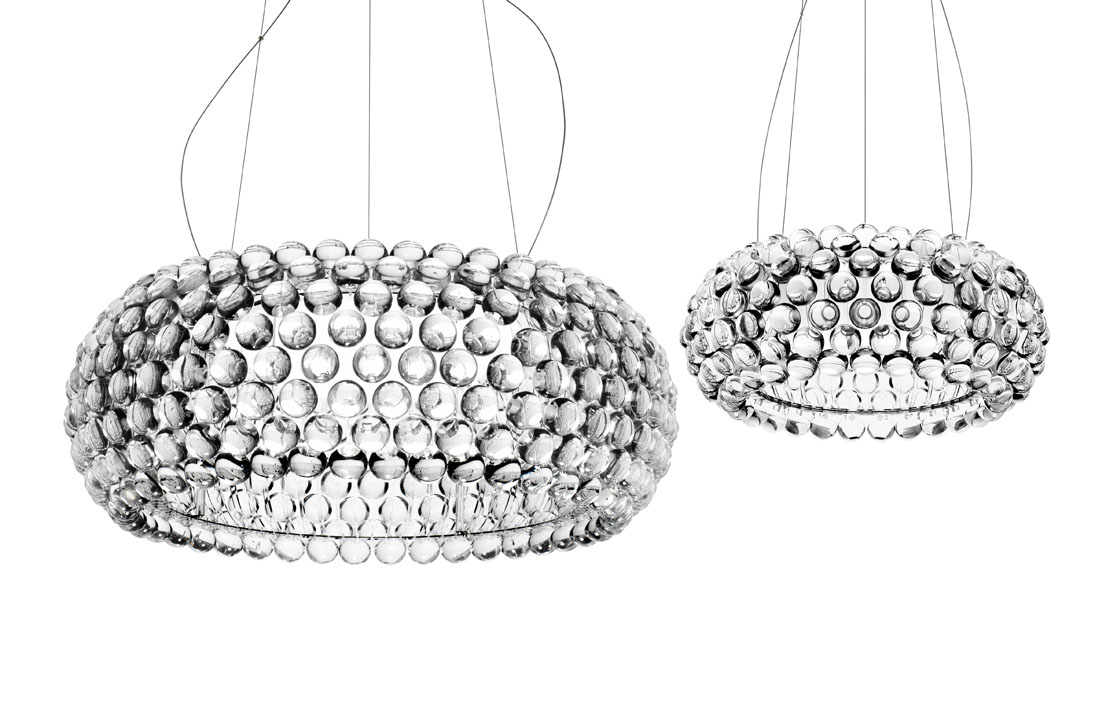

I’ve noticed that the designers who work with you often say they have drawn inspiration from a single object for their lamps: a fishing rod for Marc Sadler’s Twiggy, a bracelet for Patricia Urquiola’s Caboche—to take just two examples. Is it a coincidence?

Our catalogues are the fruit of collaboration with thirty, forty designers, and obviously each has his or her own way of working. Someone is inspired by an object, someone else by a material, there are those who concentrate on the luminous effect they want to obtain. Often, however, we realize that the inspiration comes from a preexisting element, and this is in part because, very simply, it is increasingly difficult to invent anything really new. The more the market grows and the range on offer increases, the more complicated it becomes to find completely new things. This is no longer the sixties, when design opened up to people’s needs for the first time. Today we work in a situation in which the market is absolutely saturated. This is why many designers draw their inspiration from common objects which their imagination and skill are able to turn into successful lamps.

Caboche, design by Patricia Urquiola and Eliana Gerotto for Foscarini, 2005.

How do you establish a relationship with the designers: do you come to them with a brief or do you accept from them an idea that you then develop together?

Usually the first collaborations stem from concepts proposed by designers. Then when we get to know one another and the characteristics of the individual designer become clear, it can happen that we come up with a precise brief to develop.

As you were saying, you have a very large pool of designers: is their selection and that of the designs to be worked on made on the basis of a specific criterion?

We are constantly analyzing our catalogues to see what elements need further development. In concrete terms, this means that we know which lamp we don’t have or which is coming to the end of its life cycle and needs to be replaced with new technology and new materials. We are inclined to identify the product first and then the designer, not the other way round. Between a product designed by a big name and one conceived by an up-and-coming one, our criterion is to go for the good design, not the designer. We choose it if it has characteristics that are valid for Foscarini and covers a particular gap in our range.

In fact you have a very diverse catalogue, which not coincidentally you describe as kaleidoscopic. Could this propensity for variety stem from the fact that originally Foscarini did not have a furnace of its own, and thus shared facilities right from the start, forging multiple ties?

In reality we cherish the freedom to utilize different materials, the ones best suited to the realization of a particular lamp. This flexibility allows us to range widely and to have products that may be very different from one another, but are united by the common aim of producing an emotional reaction without impairing function and innovation.

You are in a region that lives from its crafts, which form the basis of much Italian design: does this aspect make itself felt even in a company like yours that relies on mass production?

Certainly, in part because no Italian manufacturer produces millions of pieces. I’d say that ours is a world of advanced craftsmen. Blowing glass, or treating metal as in the case of Twiggy, requires artisans of this kind. Behind our lamps there are manual skills, men who know how to work with their hands, not machinery. This is a very important factor for Italian design, and one which we must stick to, especially at a time like this when manual knowhow seems to be an endangered species.

Twiggy, design by Marc Sadler for Foscarini, 2006.

You joined Foscarini as a designer and then took charge of the company. Are making a lamp and running a business two versions of the same project?

The whole of life is a project. It’s not enough to create the product, you need to understand how much to invest in a catalogue, in a presentation, in the design of a stand. This means having an idea, doing research on how to put it into effect and then turning it into a concrete venture.

Sponsorship is another way of doing business. You are demonstrating this with the magazine Inventario, recently awarded the Compasso d’Oro, and with the sponsorship of the Architecture Biennale. In this you seem to be taking an “Olivettian” approach that counts on the culture of design rather than on parading the brand.

That’s the way we’re made. But it’s a choice too, as we are convinced that culture is the natural milieu for designers, who are our reference both for the design itself and for the market. We think that culture helps people to understand our products. For we are a manufacturer of products: Urbinati and I started out as designers within the company, we are not commercial partners who invented a brand for themselves. Attention to the design and the product is our way of working, it’s in our DNA.

To conclude: are there any products that would you like to make, that you wish you had never made or that you would never make.

The product I’d like to make is the next one. Each new line of research is a challenge to take on with enthusiasm. The product that I wish I’d never made doesn’t exist, because ours are always the result of precise choices. When we present a product, or rather a prototype, we know that it will go in the catalogue and we have chosen it with conviction for this reason. Many companies present what they call new things, look at the reaction from the public and then decide whether to put them into production. This is not what we do: if we choose to make an object it’s because we are 100% sure of it, long before we get any feedback.

Spokes, design di/by Vicente Garcia Jimenez e/and Cinzia Cumini per/for Foscarini, 2014.

Carlo Urbinati and Alessandro Vecchiato

Lightwing, design by Jean Marie Massaud for Foscarini, 2014.

Rituals, design by Ludovica and Roberto Palomba for Foscarini, 2013.