19 July 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Walter Niedermayr’s turn.

Klat #03, summer 2010.

In 2001 Eikon – the El Croquis of photography – did a special issue on Walter Niedermayr. The title was Raumfolgen, literally “sequences of spaces or consequences of space.” Surprisingly enough there were no Alps. Just corridors, underground tunnels, clinics. Series of pictures taken in health care facilities. The same continuum gaze found in the next study: prison cells, Berlin-Tegel penitentiary, spring 2003; Krems-Stein, fall 2003; Gerasdorf youth detention center, Vienna, 2004. One of these images, in a large print, hangs in his studio in Bolzano. A modern building, in the first industrial belt, which in Alto Adige means the blink of an eye from the green-gold roof of the cathedral. An aseptic open space: tables, plotters, a dozen books or so. Shift your gaze by sixty degrees and the mountains, which you had imagined distant, are back: in a work, behind the glazing, in his latest project on Iran, where sand-tone landscapes yield to the optical white of a ski resort. You tie up the threads of the discussion: the Alps, the cells, the intense dialogue with the Japanese studio SANAA. But, above all, there is research that pursues a single obsession: space, according to Walter Niedermayr.

This is the first time I’ve seen such an orderly studio: how long have you been working in here?

Four or five years.

How does the work happen in this studio?

I don’t spend much time here, I come for a few hours every day. It’s run by Patrick, my assistant who works on the images.

And when you’re not in the studio?

I work on my projects.

Francesco Jodice, in an interview, said that the condition of the photographer is like that of a Caspar David Friedrich figure: a lone person on the edge of the mountain…

Maybe one hundred years ago (smile, ed.). Today, wherever you go there are people. I am never alone, it is rare even when I make solitary excursions in the mountains.

What brought you to photography?

I am self-taught, I did not have any specialized training. When I was young I worked in Germany, for Siemens, in the technical division: electronics, computers, hardware. In those years I had already started to take pictures. I was very interested in experimental film, too. Unfortunately, for economic reasons I did not pursue that interest, in that period.

What period was that?

1975-77. The next year I returned to Bolzano. I worked for a software company and continued to work on photography, but without haste.

Your first photography project?

The first of any importance was a research project in Alto Adige on a silver mine, a place of historical significance during the time of the Fuggers of Augsburg, who from Germany held European power over mining. I documented the site, analyzing the social background. The images were still in black and white.

What kind of camera did you use in the beginning?

A 6×7, manual.

Did you develop the film in a darkroom?

Yes, at the time. I still have a darkroom at home, but I no longer use it.

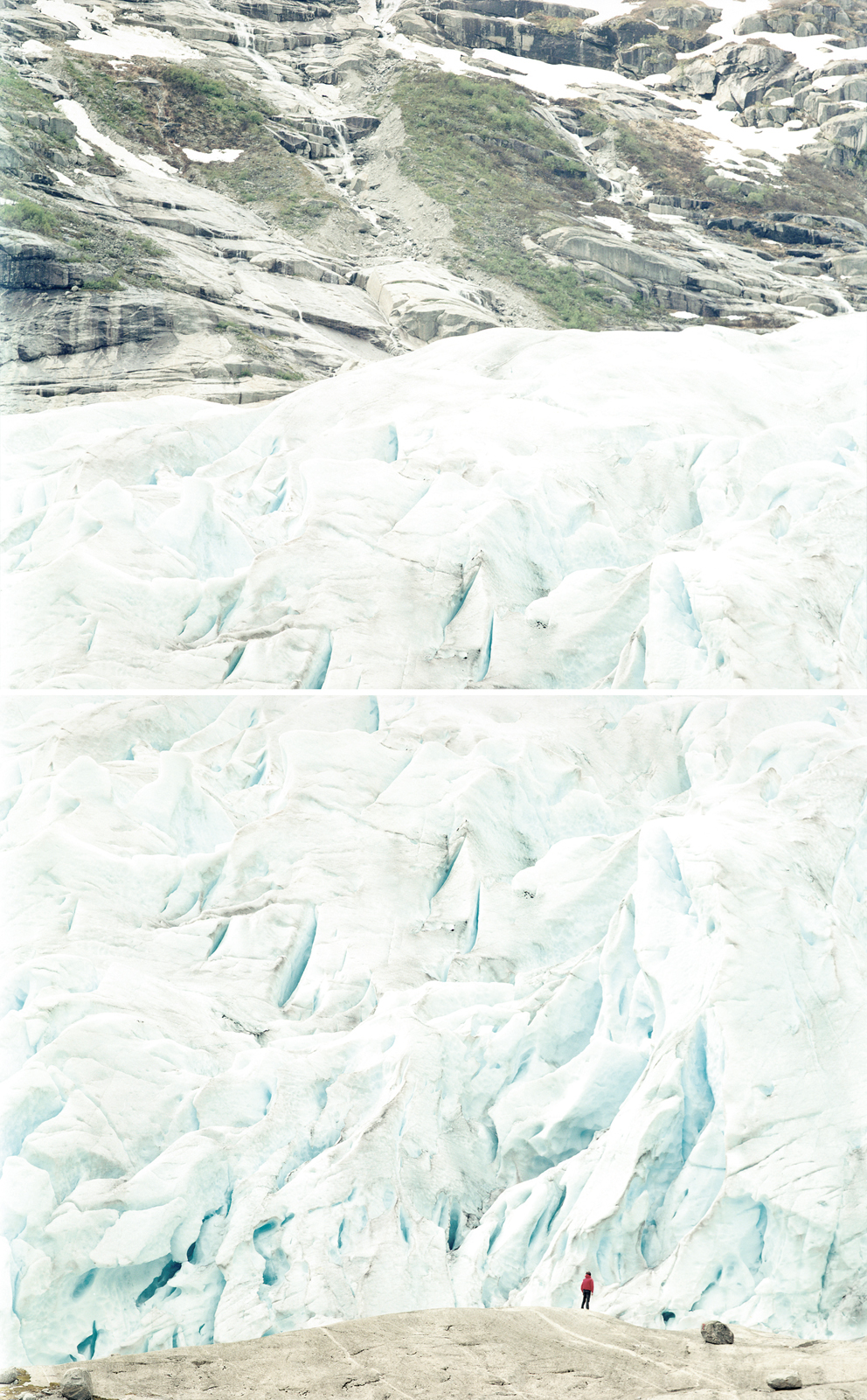

Walter Niedermayr, Nigardsbreen, 1/2002. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm

Do you miss it?

I liked it, but it was complicated. I would spend entire nights in there, developing, printing, enlarging. I did it on my own: I was fascinated, I wanted to understand how the process worked. Today I still work analog, I use film, but then we do scanning, digital processing, and then prints. Everything has changed in just a few years.

Ansel Adams, a grand old man of photography, said: “I have often thought that if photography were ‘difficult’ in the true sense of the term – meaning that the creation of a simple photograph would entail as much time and effort as the production of a good watercolor or etching – there would be a vast improvement in total output. The sheer ease with which we can produce a superficial image often leads to creative disaster.” Do you agree?

It depends on what you want to do with the photographic medium, on how you use it. Technique has never been a problem for me. I managed to learn by myself. Of course I also got to know a number of photographers. For example, one fundamental acquaintance was Lewis Baltz, one of the protagonists of the New Topographic period. His research on landscape had an influence on my work. In particular, the Park City project, done in the early eighties, near Salt Lake City, the second home of Americans: debris, buildings under construction, devastation of the territory. Years ago I went to visit that part of America, I was very curious to see what had changed. I am also fascinated by Baltz’s more recent works, his language is still very contemporary. Another photographer that interested me was Stephen Shore.

Both Baltz and Shore have worked on landscape. In much earlier times, even Vermeer used the camera obscura for many of his paintings, certainly for the Little Street in Delft, reproducing on the canvas what really appeared before his eyes. What relationship do you have with the reality you photograph?

I think the image is a thing in itself: the photograph, in the end, is a two-dimensional surface. There is a relationship between what we photograph and reality, but what the image narrates for us is another reality itself. It is a transformation of the visible. I’ve always been fascinated by the relationship between the reality of space and the reality of the image.

Germany, Italy. Technology and computers: an abstract, mathematical universe. What urged you to come to terms with the physical landscape?

To start by working on the Alpine landscape was rather obvious, given the fact that the mountains are a topography that is very close to me, and has always piqued my curiosity. As a child I often went walking on the mountains with my father, it is the landscape that surrounds me. My interest in the Alps came from the change of mission of these places. Over the years much has changed. Tourism has grown by leaps and bounds.

Framing is the simplest way to eliminate something from our retinal field of perception. With framing, one makes a window on reality. At times it is a portion motivated by a whole. What gets excluded?

I think that every image is just a fragment of something much more complex. From a scene, I try to frame what interests me: the landscape that is used by man, that is structured. The pure landscape, without human impact, doesn’t fascinate me particularly. Maybe it doesn’t even exist any longer, man has already been everywhere.

For Italian photography, the event that contributed more than others to launch a radical change was the project Viaggio in Italia (Italian Journey, ed) by Luigi Ghirri. That was in 1984. The project, an exhibition and a book, involved a group of young photographers: Gabriele Basilico, Mimmo Jodice, Guido Guidi, Mario Cresci, Roberto Salbiati, Olivo Barbieri, Vincenzo Castella and Giovanni Chiaramonte. What type of link do you have with that period?

It was undoubtedly a very important time, which may somehow have influenced me. Today, though, the way of thinking about photography has changed a bit. I think that photographing the landscape with the aim of producing a pure record no longer has the sense it once did.

If we look for the origin of this interest in landscape, important figures of reference include the Alinari brothers, Giuseppe Pagano and Paolo Monti, Mario Sironi. But also the great Americans, from Walker Evans to Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank, William Eggleston. Looking at Europe, we should mention Bernd and Hilla Becher, with their cataloguing of industrial architecture. With such a dense past, is there still a way to go beyond the “tradition”?

When I did my first series, in 1987, I wondered if it made sense to give up the work on single images, because the single image then becomes an icon. The truth is that what we see on a retinal level is never a single image, but multiple points of view. Thus the series. With this method, I have tried to go in another direction. I also believe that we include, in every shot, what we carry around inside us: culture, primal perception, everything that goes into our own story. It is only with this heavy equipment that we make our images. If we see photography in this light, every author has his own specific gaze that goes beyond schools, beyond tradition.

Walter Niedermayr, Raumfolgen, 159/2005. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Getting beyond tradition also means considering the presence of a human landscape. Much landscape photography continues to exclude that.

A certain type of photography cultivates the obsession with clean spaces, without people. Landscape and architecture, or just space, exist with people: if there are no people, there is no space. In my works on the mountain environment, the presence of people is essential: people give an idea of the scale, they tell us where things are, the size of a surface. They are a parameter of reference.

Baudelaire said that photography is the “refuge of failed painters.” Even today, the relationship between art and photography is controversial. War reporting is often shown in exhibitions in places usually devoted to art.

I see photography as one medium that is available to art, a medium that can be art or not: it depends on what the artist or the photographer does with this medium, on the research conducted with it. The matter of who defines what is art is a different question. Personally, I don’t know if I make art, I have never said that. Of course, then there’s the market…

Photography and the contemporary…

Contemporary photography is defined on the basis of the relationship I have with the contemporary world. It is related to the way I move, the things I do. Today the relationship with the landscape, perhaps, has become more direct, immediate. There is no longer that attitude of contemplation, like Caspar David Friedrich. My interest in the photographic medium is to render visible what, in part, can go beyond normal representation. Photography cannot replace the aura of the original, so it asks itself about its role as a means of expression: it asks itself what it can point out and reveal, without claiming to represent the truth.

Among your recent works, there is also the one in which you go head-to-head with the Japanese studio SANAA, namely Kazuyo Sejima, director of the next Venice Architectural Biennial, and Ryue Nishizawa. How did you begin working together?

I met them in the eighties. They already seemed like very interesting architects back then. At the end of 1990 I received an email from their studio. They had found a book of mine in Spain and asked if we could meet in Tokyo, to show me their works of architecture. In that period I was preparing an exhibition in Japan. We met, and found that we had some common interests that were not so far apart.

What attracts you about the architecture of SANAA?

It is a very essential, apparently simple architecture, I’d say it has a complex simplicity, with a tendency to relativize the relationship between form and content, while always remaining very functional. It is never spectacular, though they work on the cutting edge of feasibility. In our case, it is a sort of ambivalence of architecture, underlined by the use of glass and transparency. In photography, I too try to defy the limit, that of the visible, of representation. This is a central aspect of my work.

Walter Benjamin said it is easier to grasp a work of architecture through the camera than in reality. What happens when architecture is seen by an artist?

SANAA have never thought of me as a documentary photographer. I am interested in conveying a subjective perception, that belongs to the image. My way of working in series is opposed to the traditional conception of static space, and perhaps it conveys the dynamic idea of the perceptive itinerary. Already, at the start, it was clear that my pictures were not documentation, but research on their architecture. The projects by SANAA that have certainly fascinated me most are the 21st Century Museum at Kanazawa, the Glass Pavilion of the Art Museum of Toledo, Ohio, and the latest project, the Rolex Center in Lausanne, Switzerland, maybe the most interesting of all. What strikes me is the experimentation with a new way of considering movement inside a space: the direct experience of the place is different from one’s perception of it. It is a bit like walking in a hilly landscape…

Ruff has investigated Mies van der Rohe for years: are there iconic works of architecture with which you would like to establish a dialogue?

I wouldn’t know. Ruff has another approach. Mies van der Rohe is part of the history of architecture, a classic. The work of SANAA is very contemporary. Sejima and Nishizawa live now and design now, in a way that is very democratic, in some aspects.

I imagine you have visited their studio in Tokyo: how did you survive the creative chaos there?

That’s Japan. For us Europeans it may seem chaotic, but you get the sensation, in any case, of a very systematic order. There are many people, working in very limited spaces. All this requires a lot of discipline and respect for others. Recently they changed their studio, but the atmosphere is the same: twenty, thirty people all working together, day and night. A flow of energies that becomes calmer in certain moments, thanks to the mitigating presence of a certain number of European assistants, who by nature have other rhythms. It is another way of thinking about the profession, Kazuyo works very hard too. For us Europeans it is a very different, almost dazing experience.

SANAA Tokyo, Niedermayr Bolzano: why have you chosen to live far away from the places that are usually indicated as the cultural centers?

I believe we all make and choose our own centers. Today, if we are interested in things, in experiences, we can easily reach them, and get information. Clearly there are places where there is more movement: Berlin, London, New York. In the end the quality of life here in Bolzano is not bad. At times, if I feel isolated, I go somewhere. I travel often. I like to stop for a while in another place, and then come back here.

Walter Niedermayr, Kitzsteinhorn, 32/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

For years now, art photography has always expressed itself in extralarge format, almost as if the format itself could provide the aura. What is the importance of size in contemporary photography, and specifically in your work?

Format is definitely something to decide on in a precise way, without necessarily considering the dictates of the market. At the start, I think the large format was partially motivated by the desire to escape from the photographic rectangle, a sort of shortcut to meet the art world halfway. In my research the size depends on the content of the image. I also consider the relationship with the space where the work will be shown. From this viewpoint, I may also decide to print things very small. You have to see how you want to construct your own show. Behind you there is a diptych that is part of the project on prisons: I have used that same image in a very small format, in New York, and in extralarge size in other contexts. It depends on the situation.

From format to number of prints. According to Thomas Ruff, the limited edition is handy. It is a way of considering a work complete, closed. And it helps to boost prices. What do you think?

I do editions of six. Clearly the price changes once you have made this decision. When the six copies of a work are printed, the edition is finished. Of course photography offers you the possibility of making infinite images, but a choice of that kind requires other contexts.

Market, prices, galleries. What’s the atmosphere right now?

I believe artists should be more independent, they should also do projects outside the circuits of art and art galleries. The gallery has an important role if it considers itself responsible not just for its own affairs, but also with respect to the artist, to facilitate his growth. In periods of economic difficulty like this one, the qualities of a gallerist become more evident. Maybe I’ve been lucky, because I entered the circuit years ago. Today I hear about other artists who have problems with galleries, which are tending to vanish, in this period, or to invest less.

You have galleries in New York, Milan, Stockholm and Berlin.

As I said, I’m not complaining.

How do you work on an exhibition?

I always start with the space, a floor plan, and then I start to think about what can be done there. In the past I experimented with the use of renderings. I tried it, but I discovered it doesn’t work very well, so in the end I changed everything. All I need is paper, I can imagine things that way. For now I have always shown new works, for the most part. I haven’t done any retrospectives yet. Every thematic exhibition requires about six months of work. Though in the end, I must admit that to finish a work I need to feel a certain amount of pressure…

Let’s talk about books.

With respect to an exhibition, a book is something else. Another perception. Books interest me very much. I try to work with graphic designers who understand my way of working. Often it is very hard to comprehend each other: at times I have the impression that lettering does not establish a harmonious dialogue with the images. For Walter Niedermayr/SANAA I worked with a Dutch graphic designer: at the start we argued often, there were misunderstandings. It was a rather demanding process: but in the end a very beautiful book emerged.

How do you do your editing?

First I try to organize a nucleus of images, then I try to put them in a sequence. I take them home, I put them on the floor, I move them around until I see that the thing might work. Then the graphic designer arrives and wants to change things. It is a continuing process of changes, a give and take of ideas.

How do you defend yourself against the hyperproduction of images that surrounds us?

I concentrate on my images, on my way of seeing them. To defend yourself you also have to be very rigorous about the choice of images, and not produce them endlessly. Also by making fewer books. The multiplication of images through books leads to a sort of inflation. Another possibility might be that of being very radical. Perhaps it is enough to constantly question the meaning of your work.

How many books have you published?

In twenty years I have done nine monographs.

Walter Niedermayr, Raumfolgen, 236/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

One of the recent books is Station Z: Memorial Sachsenhausen, Walter Niedermayr/HG Merz.

Station Z is the name of the cremation oven of the concentration camp of Sachsenhausen, one of the first Nazi camps. From 1936 to 1945 more than two hundred thousand people of about forty different nationalities were imprisoned at Sachsenhausen. Years ago, the German architect HG Merz designed a memorial: an abstract structure, almost a sheet that protects the traces of the place. When I was asked to work on this, for me it was important to understand what would be the right time of year. I was there in January, it was quite cold, and there was a certain light, a certain atmosphere that made it possible to do the work. Before beginning to take pictures, I visited the place twice, for a better understanding of its history, the context, why this zone was selected, just thirty five kilometers north of Berlin.

Don’t you think that to represent a place like this – so laden with weighty emotional and historical character – through an aesthetically complex and refined image, might generate a short circuit?

The same question is raised by research projects like the one on the prisons. There are places where it is very difficult to stay, for me. After three days at Sachsenhausen I had the sensation that the place was expressing what had happened there. Though you can no longer see the traces, it is impossible not to feel them, they are in the air. Every step you take, you cannot avoid them.

What is your relationship with color? Over the years your works have become more and more desaturated.

The discussion on color is infinite. When I started taking photographs, and was using black and white, I already had the impression that the world of photography might be too full of contrasts. After having discovered the work of Timothy O’Sullivan, which struck me because of its soft black and white, the desaturation of color seemed more natural, closer to what we perceive. Now I realize that I often go beyond that, pushing the limit. It is as if I were seeking an increasingly big distance from the rather dated concept of saturation, which if you think about it is dictated by what the industry tells us: this would be right, it will sell better. I love neutral colors, I like a white that is more cool than warm. Working on mountain landscapes I often have white: precise, clean, it balances all the other colors.

With today’s digital technology, Photoshop and plotters, the eye is accustomed to imagining/seeing results that take concrete form in images after at least three passages. This also happens in publishing: first there is the computer monitor that shows us the image in one way, then there are the proofs, then the printing on paper. With all these passages the eye has become used to dealing with three “deceptions.” What does Niedermayr see and imagine when he looks at the world through a lens?

I believe that already back in the darkroom there were many possibilities for manipulation. Today, with digital photography, these possibilities have simply been multiplied. You can do anything. Then you have to decide what you want to do. For me it doesn’t change that much. It changes, in the sense that I no longer have to use the chemicals that were needed for developing. The same is true of color: yesterday you could filter it by analog means, today there is Photoshop, which has very great potential.

What are you working on now?

I am preparing a publication with the works I did in Iran. I’ve been there three times: 2005, 2006, 2008. I photographed the landscape of the historical and the modern city. Not just in Tehran, but also in other centers: Isfahan, Shiraz, Yazd and other places.

Is this the first time you have worked on such a faraway landscape?

Not really, I also worked in America, Japan, New Zealand. The project in Iran was organized by an institute in Vienna that focuses on cultural exchanges with Iran. Artists, architects and writers are involved, who present their research, conduct workshops and can work for up to four weeks in that country, which is a very beautiful, very interesting place. What we hear about Iran is very distorted by politics. Politics in Iran is one thing, the population is another. Most of the generation of people in their thirties would like to leave or change the system. It is a difficult, complex reality.

What kind of book will we see?

The research had to do with the new that inserts itself into tradition. I was very interested in this ambivalence: on the one hand, a very long history, three thousand years and more, spanning different periods, eras and cultures, also in architectural terms. A very lofty tradition, extremely fascinating. Think, for example, about the Iranian wind towers, simple structures but also very sophisticated in bioclimatic terms. After the Islamic revolution, the recent past has introduced an idea of architecture that has produced landscapes with no connection to history. This contrast struck me. It is as if the excluding effort of the regime had imposed an abandoning of tradition, unintentionally forcing people to look to the West for other models.

Would you show us something?

Niedermayr opens a book with Arabic characters. He turns the pages and shows us the research by about ten different authors. We see Tehran, earth constructions, monumental Iran, crumbling neighborhoods, faded suburbs. Then the surprise: the optical white of a ski resort. And, once again, everything makes sense.

Walter Niedermayr, Sachsenhausen, 3/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm

Walter Niedermayr, Sachsenhausen, 23/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Walter Niedermayr, Raumfolgen, 132/2004. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Walter Niedermayr, Bildraum S, 164/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Walter Niedermayr, Iran, 155/2008. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.