10 October 2013

Don’t call him a photographer: Thomas Demand (Munich, 1964) is a complete artist of the old style. Taking the picture is just the last step in his work, almost a formality, the endpoint of a process that is first mental then manual, a matter of craft. Demand is a constructor of worlds: his models are built in the studio, entirely by hand, on a 1:1 scale, until each detail is exactly how he had imagined it. Then they are photographed with a high-resolution view camera and finally destroyed. His models meticulously reproduce real places, the settings of events in the news like the kitchen of the hiding place where Saddam Hussein was captured, or the hotel room in which Whitney Houston died, or again the embassy of Niger from which documents were stolen and used to fabricate false evidence to justify the Iraq War. Silent images, devoid of any human presence, that leave us confused: is what we’re looking at real or just realistic? A question that contains another: do the visual messages with which we are bombarded every day convey reliable information? In his studio in Los Angeles, where he has been living for two years (after sixteen in Berlin and eight between Paris and New York), Thomas operates alone and produces very few works a year, since he has chosen to allow himself the luxury of not turning, like many of his successful contemporaries, into “a small corporation.” It may have been for these qualities, and for his crystal-clear intellectual lucidity, that Miuccia Prada chose him as co-curator, alongside Germano Celant and Rem Koolhaas, of the most controversial, most highly praised and perhaps most visited exhibition in Venice over the course of the Biennale. When Attitudes Become Form. Bern 1969/Venice 2013 is the restaging, as obsessive as it is impossible, of the mother of all exhibitions of contemporary art, the show of the same name curated in 1969 by Harald Szeemann. The operation conducted by the Fondazione Prada is on the borderline between accurate reconstruction and almost theatrical pretense: from the spaces of the Kunsthalle in Bern, reconstructed inside the 18th-century Palazzo Ca’ Corner della Regina, to the exhibition itself, re-created on the basis of dozens of images and documents. We have talked to Thomas Demand about it.

Thomas Demand, Pacific Sun (detail), 2012, Video. © Thomas Demand, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / SIAE, Rome.

What role did you have in this exhibition?

I think that Miuccia brought me in because my work turns on reconstruction. I read photographs and here all we had was photographs: we had to bring back to life something that only existed in pictures. In addition, I’m the only one of the three curators who can’t remember the original exhibition because in 1969 I was still a child: so my vision is a more detached and objective one. Lastly, during the preparation of the exhibition I realized that I could also lend credibility to the project as an artist, and thus someone able to interpret the intentions of the artists. The problem with Szeemann is that each of his exhibitions was an exhibition on Szeemann. So as well as an exhibition on Szeemann, it was important to succeed in creating an exhibition on the art that had been put on display.

What obstacles did you run into in the definition of the project?

We discussed what it was possible to do and what not, and my position was that we ought to be as faithful as we could to the original. Today we would never stage an exhibition of this kind: there are works placed on the ground without a support, something that would be simply inconceivable nowadays. The other surprising thing is that half the works in the exhibition are by people we’d never heard of, while the other half are by artists who have had an extraordinary career, like Bruce Nauman or Richard Serra. So we wanted to preserve the density of the context that generated this exhibition. But it is impossible today to re-create the sensation of disorientation it aroused at the time: we know too much about this art. Hence we decided to wedge a museum space of the sixties into an 18th-century palazzo, producing a different sensation of disorientation: you never know where you are.

Did that generation of artists influence your development?

Yes, a lot. I grew up in a town near Munich: my best friend, and in a small town your best friend is someone you spend eighteen hours with a day, was Pepper Herbig, the son of one of the greatest collectors of that kind of art. His father collected works by Beuys, Dieter Roth, Daniel Buren, and we used to play ball in the midst of them. In the garage there was a VW bus used by Beuys in one of his works, while in the house they had pictures by Edward Ruscha that looked to me like book illustrations. I can say that I literally grew up surrounded by those works, before I even knew they were art and long before seeing them in museums. In their kitchen I met an elderly gentleman: he was Marcel Broodthaers. But all this was just a backdrop: it wasn’t Art with a capital A, but a strange hobby of my friend’s father.

From left to right: works by Eva Hesse, Bill Bollinger, Gary B. Kuehn and Keith Sonnier.

When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

Almost a precocious call for the mingling of art and everyday life.

Just yesterday I met Kaspar König, who thinks that this exhibition has been made such a legend—all the courses for curators start out from When Attitudes Become Form—that people have forgotten how banal these objects were. Not in the sense of their significance, but of their reality: they were simply objects, and today as a result of the almost religious approach that we take to art it is impossible to see them for what they are.

And what art influenced you once you started to study?

If you were to take a survey among all the students who enroll in academies of fine arts, you’d find that 85 per cent of them do it for the wrong reasons. Well, I’m part of that 85 per cent. It’s very hard to understand what you have assimilated in your youth, what influenced you, but one thing I am sure about is that art offers you a very strange way of thinking about the world. The practical way of acting in the world—of the sort: “I’ll take a vaporetto at half-past five, then I’ll go and eat”—doesn’t apply to art. If you want to buy a pretzel art is of no use, but if you want to connect with someone who lived 500 years ago without any need for words, then art can help. If I look at one of Holbein’s pictures it’s perfectly clear to me what he has painted and why he has painted it like that: he perceived the same things I perceive. Art makes you feel that there is a very profound and very beautiful connection between all human beings.

Is that why you decided to become an artist?

In the end I was attracted by this strange realm of knowledge with which it’s so difficult to impress your friends. What fascinated me about art was its brusqueness and impenetrability, the fact that you never immediately understand what it means. And that you love it even more because of the effort that you had to make to understand it. I think that the fascination of this exhibition stems precisely from the fact that here people sense that the power of art does not lie in money, and does not reside in museums, and that they ask themselves whether that stuff over there in a corner is simply margarine or is art.

From left to right: works by Gary B. Kuehn, Reiner Ruthenbeck, Richard Tuttle, Bill Bollinger, Alan Saret and Keith Sonnier. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

One reads everywhere that your works are derived from photographs. But which comes first, the photo or the idea?

Either of them can, but it’s mainly the idea: there is a path that joins one work to the next, so it can’t be repeated. For a long time, for example, I was looking for a photo reproducing a model of the kind you find in a scientific laboratory, like those mazes for rats that are used in behavioral experiments. I was interested in representing the idea that the models are not necessarily models of works of architecture, but can also be models for the understanding of reality. I looked for that photograph for years and never found it, and while I was looking I happened to open the newspaper and come across a picture of the room in which the ballots were recounted in Florida, during the contested election of George W. Bush. It was an image that we had seen over and over again for weeks, but looking at it I realized something: elections are like a behavioral experiment in which you artificially reduce the choice to two candidates. And then I did a work on that room, which suddenly seemed to me like a laboratory for rats.

Your images preserve the traces of emotionally highly charged situations, often based on violent news reports. How come?

The reason is that the majority of stories that catch our imagination are of this kind: the photos in newspapers are almost always connected with violent events. What interests me is getting to the root of what happened, imagining being the person who was there at that moment and trying to reconstruct the facts in an objective way. Take Saddam Hussein’s kitchen for example: at the time Saddam was painted as the most evil person in the world (and maybe he was, I don’t know). The photo of Saddam Hussein’s kitchen was taken by the soldiers who found him, and if you look at it all you see is a kitchen, with the same Tupperware as I have at home. So you say to yourself: this is the devil? The most wicked person in the world cooks eggs in the same frying pan that I use? All this has an extraordinary power: you say to yourself, is it possible for this long story to end simply with this image?

Which also makes one reflect on the power of the image in the times of the internet.

This is a development of the last ten years. In all the photos we see online the person who has taken the picture counts more than the quality of the image. The images that strike us most are the ones in which the event is completely connected with the photo, or is even taking place just to be photographed. Let’s take the case of the torture at Abu Ghraib, in Iraq again: what happened there was dependent on the photo, not the other way round. What I try to do is this: convey the crudity of the scene without having to tell the whole story.

Robert Barry, Uranyl Nitrate (UO-2 (NO-3)2), 1966; Daniel Buren, Affichages sauvages, 1969. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

How did you start working with this process of reconstruction and reproduction?

It has been a gradual progress. In the beginning I used to make very small sculptures and then throw them away, because I lived in a very small apartment and didn’t know where to put them. So I would look at them and think that if I needed to I’d always be able to make them again. Then a teacher told me I should record them, to see if I was getting anywhere. And so I started to photograph them. But the pictures were terrible, because I didn’t know how to take photographs. That was my first problem. One day I saw a pair of photographs and thought that they worked really well together. And I asked myself: what should I do now? I learned how to take photographs.

And so one day you started to make sculptures in order to be able to photograph them.

More than anything else I realized one day that photography was not mere documentation. At that point the process was more important than the object I was photographing, and I thought: what happens if I take a photo of a photo, if I use as a source something that is not an object, if instead of using my own experience I use somebody else’s? So I photographed a place that I remembered very well because I’d seen it many times in books. Many of my photos are pieces of paper that show another piece of paper, which in fact it is not.

How big are your models?

They’re all actual size. It’s the heart of my work: I create models on a 1:1 scale.

How many people work with you?

Not many, usually there are two of us, at the most three. Everything you see in the photo is constructed by me personally. If you’re a fairly successful artist you have two possibilities: you can create more and more works, and make more money, or you can say to yourself: “I enjoy what I do, I can allow myself to make just a few works and sell them at a price that permits me to realize them at the speed I want.” I have chosen the second possibility. I’ve seen many of my friends turn into real corporations. It works fine for them, but then you end up spending your time telling others what they have to do, while you would like to be the one doing things, as telling others what to do is fairly boring. In my case instead the work always passes through me: in this sense, I’m a very traditional artist.

From left to right: Michael Buthe, Untitled, 1968 and Weisses Bild, 1969; Rafael Ferrer, Chain Link Fence Piece, 1968–69. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

I’m curious to know why you moved to Los Angeles, a city where everything seems fake.

The strange thing is that Los Angeles is almost as old as Berlin, which saw extraordinary growth in the 1920s. Europeans think that there’s no history in Los Angeles, but in fact there is and you can see it: if you walk along Sunset Boulevard, for example, you see the store where Marlene Dietrich used to go shopping. It’s a city filled with stories, filled with scenery. And then it’s an incredibly productive place, and for this reason it has practically no night life. In Berlin you go out at ten, you come home at three in the morning, and you’ve talked for five minutes with a lot of people. A bit like Milan, I think. But in Los Angeles there are no bars: you go to bed at ten, but at least the next day you’re able to work.

You don’t miss Europe?

What I liked about Berlin, in the beginning, was the openness: there were so many empty spaces, empty houses, empty plots of land. It’s not that you wanted to build something, but walking around the city you had this sensation of infinite possibilities, as well as dreams and failed projects. The past was there without saying “I’m the past,” like a monument. But today Berlin has become very institutional, with the same hierarchies and the same rituals as many other places. It could be Paris or Cologne, while in Los Angeles I’ve found a healthy feeling of openness. And then the art scene here is fantastic, there are eight art schools churning out artists who once they’ve made a name for themselves go back to school to teach. As for me, I’ve understood that this idea of reinventing myself each time is extremely productive: when you arrive in a new place nobody knows you, you don’t have a whole room filled with books. You start again from scratch and it’s very liberating. This may not be directly perceptible in the things I do, but I sense it clearly.

In Los Angeles you’ve started making little videos.

They’re big videos, not little videos! My latest work is a big animated film that I showed at Art Basel, entitled Pacific Sun. It’s the most complicated thing I’ve ever done: it represents the dining hall of a ship sailing between Tasmania and Sidney that runs into a very powerful storm. The film is shot entirely in stop motion, frame by frame, and everything has been done by hand: nothing is real, not even the movement. I had to hire a big studio and work with twelve animators of the old Disney school. We saw each other every day for six months. The whole thing lasts two minutes, but it cost as much as a good apartment in Milan! My producer told me I was crazy and said that with the same money I could have made a feature film. But what can you do? It’s a work of art.

Thomas Demand, Hole, 2012. © Thomas Demand, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / SIAE, Rome.

From left to right: William T. Wiley, Slab’s Axe in Change, 1968 and Paul Cotton (Adam II), Table of Contents, 1966. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

Ger van Elk, Tres Qualitates Lucis, in Modo Rustico Californiae, 1968–69. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013. Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

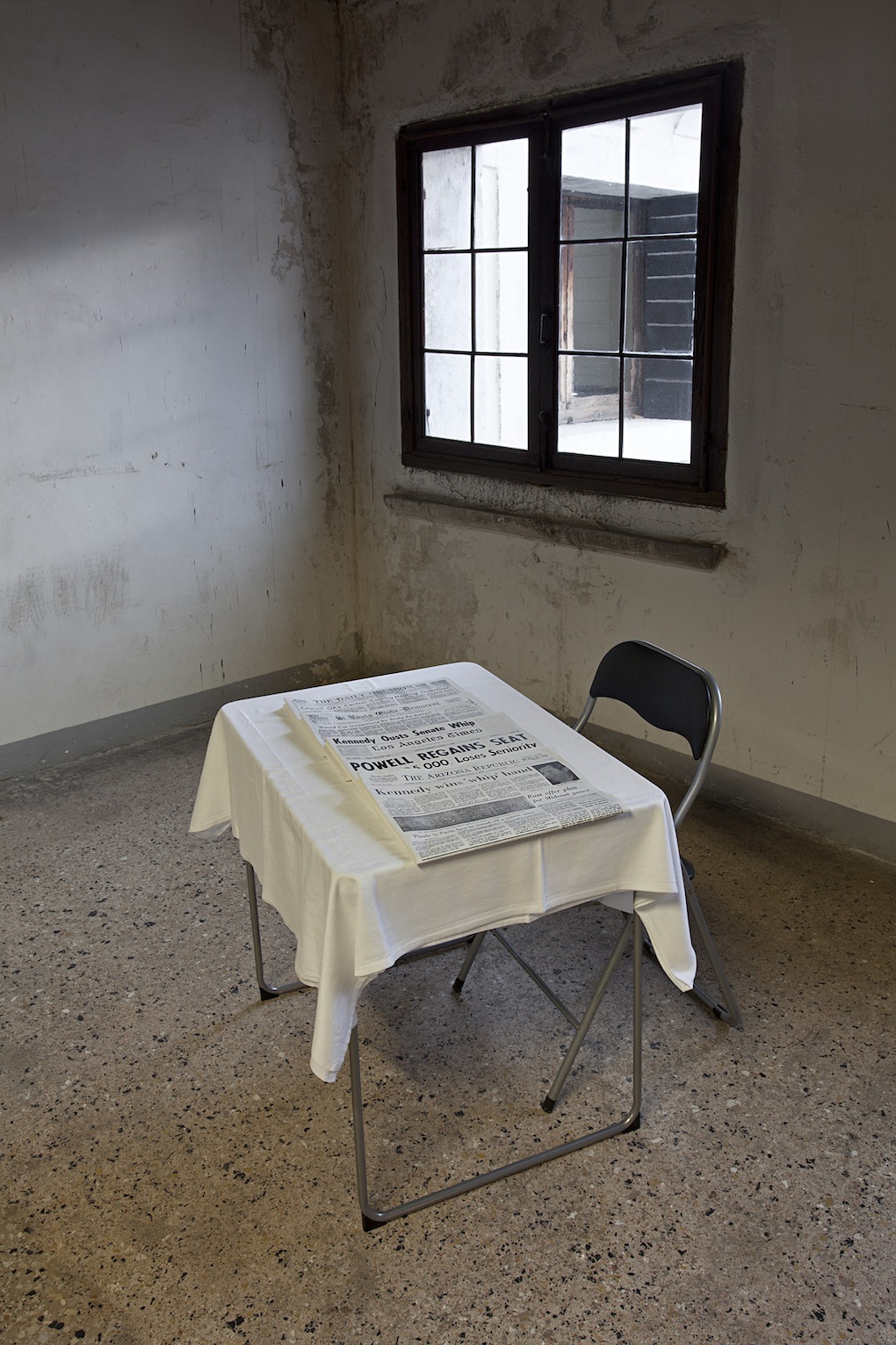

Allen Ruppersberg, Untitled Travel Piece, Part 1, 1969. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

From left to right: works by Keith Sonnier, Richard Artschwager, Richard Tuttle, Alan Saret, Gary B. Kuehn and Walter De Maria. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

Giovanni Anselmo, Torsione, 1968. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

Neil Jenney, The Siegmund Biederman Piece, 1968. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

![Frank Lincoln Viner Never, Ending Surface, 1969. Pier Paolo Calzolari Scalea, (mi r fea pra) [Monumental Staircase (mi r fea pra)], 1968. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.](https://www.klatmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Klat_Thomas_Demand_When_Attitudes_Become_Form_Venice_2013_14.jpg)

Frank Lincoln Viner Never, Ending Surface, 1969. Pier Paolo Calzolari Scalea, (mi r fea pra) [Monumental Staircase (mi r fea pra)], 1968. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

Gilberto Zorio, The Fire Has Passed, 1969. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

From left to right: works by Mario Merz, Barry Flanagan, Richard Artschwager, Robert Morris, Bruce Nauman. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

Thomas Demand, Junior Suite, 2012. © Thomas Demand, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / SIAE, Rome.

Thomas Demand, Kontrollraum / Control Room, 2011. © Thomas Demand, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / SIAE, Rome.

Thomas Demand, Landscape, 2013. © Thomas Demand, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / SIAE, Rome.