25 October 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Michael Fliri’s turn.

Klat #02, spring 2010.

Subtle and nuanced, the work of Michael Fliri functions on the dual track of formal and conceptual research, going beyond mere appearances and reflections on video and performance, reasoning about both and comparing the two experiences. Fliri presents himself to the viewer and leaves him on his own, faced by changes and transformations whose playfulness or slight melancholy permit reflection on the flow of life. We took stock of the progress of his research, a path that has already developed through ten years of experience, in spite of the artist’s young age.

Last year, at the Museion of Bolzano, in the context of the exhibition New Entries!, you did a performance entitled From the forbidden zone. I recently saw some photographs of it, and I was struck by the fact that in this work, more than your previous ones, I could see an aspect of your activity that had been concealed, namely the desire to look at others. As if the presence of your face, in spite of the fact that it was a mask, had been forcefully imposed on the viewer, raising the question of the identity of the person on the other side. So who is this being that observes us?

Everything starts with the mask, but in the case of From the forbidden zone it is not just a mask, it almost becomes a second skin. Last year, during my stay in Paris at the Centre International d’Accueil et d’Echanges des Récollets, at the Dena Foundation for Contemporary Art, I sent a casting of my face to Hungary, to two guys who specialize in making products for cinema, especially horror and fantasy films. Starting with that cast and a series of drawings, together we created the face of this person. The point is that this mask can be worn only by me, if fits my face perfectly. You couldn’t tell where the mask ended and the real skin began. In the preparation for the performance it took five hours to put the mask on: a long job, and very important for the performance, because after all that time I had truly entered the character. I felt almost like another person, another creature, not just someone wearing a mask. This helped me a lot, above all with respect to what you were saying about looking at others. I could watch the others and the others could watch me, without leaving too many traces of my being, of my being Michael Fliri…

This is an aspect we’ve talked about before: the lack of interest in your body as the body of Michael Fliri, the body of the artist. In your videos and performances, you act with your body only because it gives you full control of the actions, not to be at center stage. In the case of From the forbidden zone, through the cast of your face you stage a mutation of yourself. Transformation is a key concept in your work. Thanks to the cast you obtain a new identity, a new character we know nothing about. And once again Michael Fliri vanishes, and someone else appears…

In From the forbidden zone I felt at ease for the first time in front of an audience during a performance. The action was truly minimal, almost mechanical. I sat there, on the ground, on the floor, I watched the people and they watched me. The only performative aspect was a hood I was wearing. Some people came too close and stared at me too insistently, to the point of making me feel uncomfortable, in spite of the protection of this second skin. So I felt a strong urge to close myself inside a hood. The spectators understood that gesture, and they backed off, giving me back my private space.

Michael Fliri, The polar bear, 2005. Courtesy: Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano, and Galleria Civica di Arte Contemporanea, Trento. Photo: Hugo Munoz.

You hadn’t expected to have to cover yourself more, to protect yourself from the gaze of the others?

No, strangely enough. I was convinced that the costume was enough protection on its own. I didn’t imagine that the hood would become a fundamental part of the performance.

We mentioned the concept of transformation. What is transformation, for you? What interests you about this principle?

For me transformation means new possibilities, new opportunities. Everything is in motion, not definite. The idea of the not-defined is what interests me most. I like situations in which the brain has to deal with new information, things that haven’t yet been stored, catalogued, classified.

With respect to your previous works, in From the forbidden zone you operated in the exhibition space (the Museion) without putting the filter of a video camera or a still camera between yourself and the viewer…

…yes, I generally prefer the more intimate, sheltered dimension of video, to have everything under control. Although for the International Prize for Performance…

…you worked in direct contact with the audience. I was thinking precisely about that precedent. In that case, when you served the ice desserts your mask and the movement you were forced to make, lowering your head toward the block of ice you were scraping, seemed to repel the audience that was faced by the gaping jaws of a white bear…

In the performance The polar bear, 2005, there were two different moments of exchange and watching with the audience. During the very physical part in which I scraped and shaped the block of ice, it was the bear that observed and stared at the audience. Only later, when I offered the ice, could I glimpse the people from a black hole. Thinking back, it was almost as if the bear had everything under control, with the force of its presence, while I had my mini-outing only in the most pleasant moment, that of offering, of giving presents.

Do you think the time in Paris, an opportunity for reflection, contributed to challenge you to move toward new works, stimulating your interest in audience reaction, for example?

I wouldn’t know. In general, in any case, I think it is important to alternate trips, reflections, study and work, different experiences. I always tell myself, with pleasure, that I don’t believe in the idea of progress. I believe in the transformation of things, of interests, of age. With time things change their rhythm, in a very natural way. If you can accept that, it silently enters your work, maybe without even knocking. In certain cases, perhaps, it is no longer pertinent to talk about artistic research.

Michael Fliri, Early one morning with time to waste, 2007. Courtesy: Michael Fliri. Photo: Ela Bialkowska.

Yet it is true that the interest in the spectator and the sensation generated by greater contact with him are interdependent. The relationship gets more intense when there is an effective physical contact, unlike the cases in which you operate in front of a video camera, thinking about those who will watch you later. In a live situation the relationship is more dynamic, including actions and reactions, which is what happened in From the forbidden zone…

In the case of the performances on video I usually have an idea of the results I want to obtain, in a sort of collaboration between me and the camera. The work is under control, but the final result is only probable. I say probable because in some cases I have approached real challenges, things that were hard to govern or predetermine. I’m thinking about the boat out on the sea in Early one morning with time to waste, del 2007, or the stilts on the mountain in Let love be eternal, while it lasts, in 2006. Those are two works that generated very new sensations for me, because it was not possible to rehearse and it would have been too boring and useless to try. In From the forbidden zone the sensation was similar. I was not so interested in the reaction of the audience as in my reaction to that given moment, very strong, very different from usual. I like to shift the boundaries, to put myself in new situations.

How does Shady Oak Amusement, the carnivalesque parade you did in 2008 on the streets of Trent for The Rocky Mountain People Show, organized by the Galleria Civica di Arte Contemporanea of Trent, fit into this approach of shifting the boundaries?

That was a bit different. The boundary consisted in not doing the performance alone: in not being Michael Fliri or a single person, but a group, a single organic form. There were twelve of us and I truly saw it as the action of a single body.

Was that the first time you’ve worked with a group?

Yes. Though in the case of Gravity, 2007, at the EURAC tower – the Project Room of the Museion – there were two of us. It was a video installation on five floors, showing the fall of these two people: in some scenes they help each other, in others they don’t… It is a bitter video, with a rather dramatic ending. This is the only work in which I react with another person, because I really needed two of us to be there: I wanted to show how two individuals react. On other occasions, for example in I’m in hell and I’m alone, also in 2007, the interaction happens between me and objects. In Trent, in the case of Shady Oak Amusement, a sort of Halloween parade, darker than the traditional carnival parade, it was the group that acted…

Michael Fliri, Shady Oak Amusement, 2008. Courtesy: Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano, and Galleria Civica di Arte Contemporanea, Trento. Photo: Hugo Munoz.

…a single body…

…yes, and looking back on that dynamic today we might underline the condition of the individual inside the group. The collective dimension implies that the individual no longer chooses independently, is no longer completely free. Obviously in the case of the parade of Shady Oak Amusement my only aim was to create a more organic, natural and unique action.

Earlier, you used the term challenge to define some of your works or the actions that generate them. A challenge also as a shifting of boundaries, of limits. What challenges you? What does the term mean to you?

I wouldn’t say they are real challenges. Personally, I don’t really have this idea of having to achieve something. If I think about the word challenge I think about something I have to obtain, otherwise “I lose”. We have to get beyond the concept of challenge… I don’t believe in the idea of winning or losing. In my works the challenge is much more natural, almost an everyday action, like getting up in the morning. My works are things one does: they can contain that idea of losing or winning, of course, but actually they are just things and actions that have been done, that are done or will be done.

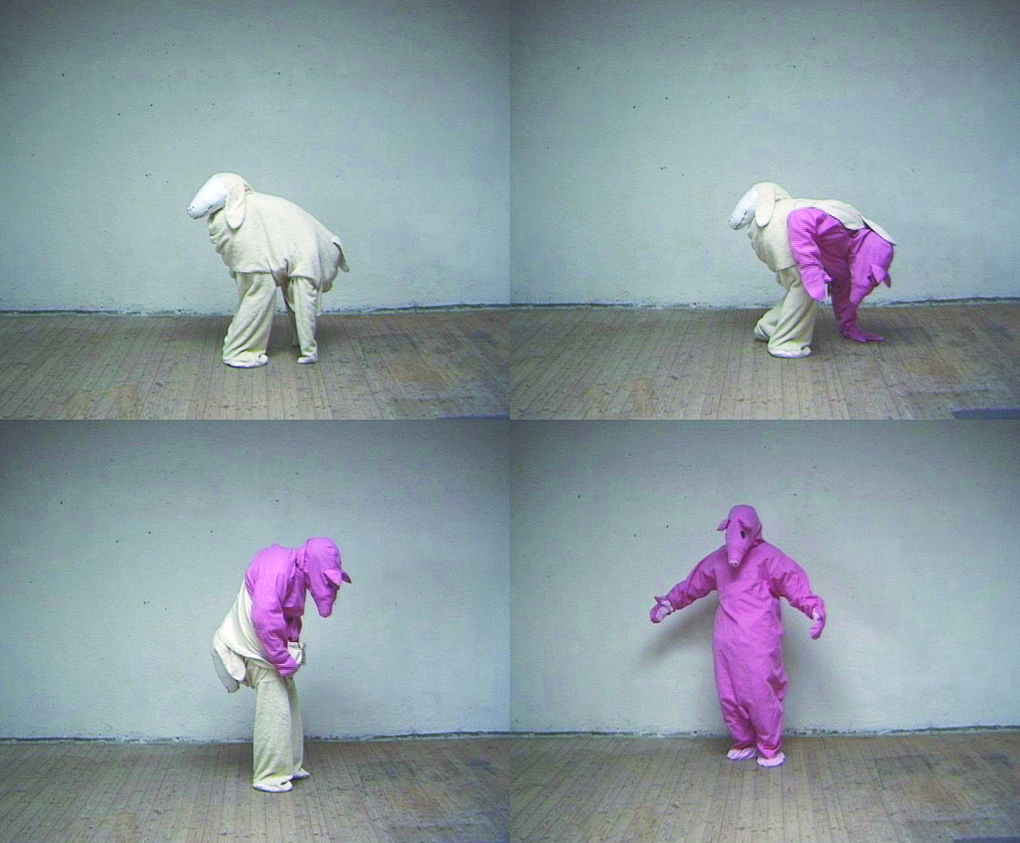

Then I’m reminded of a comment we made when we worked together in 2007 on Looking for the border, an Italian-Belgian exhibition project. From my viewpoint, as I said, your work is focused on the theme of transformation, seen as the possibility of something happening: as development, as occurrence. Let’s look, for example, at one of your first works, Come out and play with me, 2004, in which through an elaborate system of stitching of your costume you were transformed, in front of the video camera, from a pig into a sheep. And the transformation is also happening when you climb a snowy mountain on stilts, or when you float on a boat made from plastic bottles. Challenges without positive or negative outcomes, but trials that produce changes, transformations. The transformation is not something in which you win or lose: it is just change. That’s what is important.

That’s really beautiful, because change only means that things are altered, for better or worse. This means coming to terms with a new possibility.

And that is exciting.

Yes.

Your work has often been associated with the theme of irony, the balance between comedy and tragedy, humor and drama, joy and bitterness. What’s your reaction to this frequent interpretation?

I like the way you define irony, as the balance between two extremes. I think it is interesting that a work can have multiple levels of interpretation: some see it in a darker way, others pick up more optimism.

Michael Fliri, Come out and play with me, 2004. Courtesy: Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano. Photo: Othmar Prenner

To change the subject, for a moment, I’d like to ask you about your path from the mountains of Alto Adige, near Switzerland, to Bologna, then Munich, then Vienna… When did you start to think that the things you had inside you could be communicated to others?

Well, I can only start with my first work: the snowman, Der Schneemann, in 2001. In that case what I had in mind was a rather wintry, mountainy work, connected with snow and childhood. But I wanted to translate it into something else. At the time, when I was 22, I was very concerned with coming to grips with themes connected with the mountains, I wasn’t capable of directly approaching the natural element, Nature. So I decided to use styrofoam, a super-artificial plastic material, clearly anti-natural, and to install the work in an indoor space. I brought out its content. Years later, in Let love be eternal, while it lasts, I felt comfortable enough to directly address the landscape and the reality in which I was born and raised. At the start, though, I would never have been able to do that, maybe because when you’re young you want to get away from your roots, moving toward other borders, including mental ones.

Perhaps because at the start it seemed too simple, too obvious to refer to direct experiences. Or maybe because the relationship with the place of origin was so important that you might be afraid of using its most characteristic features: snow, ice, mountains…

Those fears all had very different reasons behind them, but they were real fears, that coexisted with the desire to invent a situation.

The other day, thinking about your works, my reasoning focused on two recurring elements: the mask and the performance in front of a video camera. Both the mask and the lens of the camera mark borderlines, are surfaces that indicate the border between you and the spectator, you and the physical and temporary space of the performance. In particular, the theme of the mask inevitably touches on that of identity. Do you think being born in a border zone, a region like Trentino-Alto Adige, which already has two borders inside it – the linguistic border and the border of communities – influenced you? And to what extent? Do you think there is a reworking of this boundary in your constant research on limits and identity?

I really like this idea about the lens and the mask. It’s brilliant and interesting. The lens and the mask, in my view, are like two accomplices: the first, the lens, is very objective by nature, while the mask almost always fakes something. But the lens, in its objectivity, accepts the mask, without judgment.

Yeah, I was interested in thinking about them as a pair of elements that work together. I was also thinking about that before, when you told me about the strong sensation you had during the performance at the Museion. In that case the lens of the camera wasn’t there, but there were our eyes, our lenses, that are not as objective, as serene and detached as the lens of a camera. Our eyes, as they watch, immediately express a judgment. Or a comment… Changing the subject again, in Paris you bought a gorgeous old industrial sewing machine. Do you sew your own costumes? Where did this passion for disguise come from?

I’d say it started in my youth. Up in the mountains traditional rituals still exist connected with costumes. There is the carnival, which is very important. Then there’s the Krampus, devils that run rampant in the streets of San Nicolò in December: they wear animal skins and terrifying wooden masks. The feast of San Nicolò stages the eternal struggle between good and evil, and good triumphs. In the past it was very vivid. We were talking about my very first work, the snowman, Der Schneemann. I knew I wanted to work with snow (in that case with styrofoam), so I transformed myself into a snowman. The costume called for a transparent belly filled with styrofoam, and with every movement I lost a bit of the material, which was thus added to the environment. Creating the costumes, the sculptures, everything I need to implement my ideas, I have always tried to find inexpensive creative solutions, to invent something. I’m also lucky to have friends who support me, who do favors for me. The first costumes were made by my mom, who learned to be a dressmaker, though she has never done it as a job.

Michael Fliri, From the forbidden zone (make-up), 2009. Courtesy: Museion, Bolzano, and Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano. Photo: Ivo Corrà.

I’ve always imagined Tubre as a very beautiful place, wedged and settled amidst the mountains. Would you tell me something about it?

I think it is interesting that every one of us is born in a given place: a place we did not choose. At Tubre I had my first experiences, made my first friendships, felt pleasure and sadness. Everything was natural, taken for granted, there was no other version, no other place, and at first there wasn’t even the desire to change something. Tubre is a small place, shut between the mountains. Trying to look into the distance doesn’t work, there is always a mountain to block your view. Some people feel claustrophobia there. I also see the landscape of Tubre as such a strong landmark that you cannot get lost: you always know where you are. The settlement is in a small valley, with four villages: only Tubre is in Italy, the other three are in Switzerland. We’re right on the border. The geographical border is also the linguistic border: German in Tubre, Rhaeto-Romanic in Switzerland. The religious border is different: the first town in Switzerland is still Catholic, the others are Protestant.

Lately, on the other hand, you’ve been living in Vienna: why did you choose the Austrian capital?

It all began when the city of Vienna gave me a residency for a whole year. And I think they did a good job, since I have stayed beyond that period… Before that I had never remained for such a long time in one place, I was always on the go. For this reason, in spite of the stability, my apartment in Vienna is quite empty, with nothing on the walls. Though I often think I would like to put something up. I find Vienna interesting, it holds a particular charm for me. The museums do excellent work and in general I think the Viennese love culture. Vienna prepares me for art like the five hours of make-up prepared me for the performance of From the forbidden zone… it’s an excellent place for concentrating and transforming yourself.

Michael Fliri, The polar bear, 2005. Courtesy: Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano, and Galleria Civica di Arte Contemporanea, Trento. Photo: Hugo Munoz.

Michael Fliri, Early one morning with time to waste, 2007. Courtesy: Michael Fliri. Photo: Ela Bialkowska.

Michael Fliri, Der Schneemann, 2001. Courtesy: Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano. Photo: Othmar Prenner.