6 March 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Peter Zumthor’s turn.

Klat #05, spring 2011.

Here I am back in Haldenstein after a gap of almost two years. The studio is bursting with maquettes and models. There hardly seems to be any space left to walk and find your way among the things; a few empty spaces on the walls in which to put up drawings, sheets of paper and pictures. There is no letup in the work in Peter Zumthor’s house and studio. Outside the Swiss Alps are cloaked in silence, while the Rhine flows under the bridge that connects the village to the small city of Chur. Zumthor, who was born in Basel, decided to come here to live and work many years ago. Since then dozens of collaborators have been working at his side forming a team of designers. Young architects from all over the world come to him to take part in his work, to learn how to do just one thing: architecture. Perhaps there’s no need to add anything else. “Very high quality and precision, obtained through endurance and perseverance,” is how he puts it. Peter Zumthor checks every detail, adjusts proportions with extreme care, takes the project the closest as possible to reality: to test it, to imagine the space as a place that one day will be lived in, a place that will soon be crossed by air and light. In this brief conversation recorded in his studio, we talk about his work and his youth. Peter hangs up the phone after a long call to the United States. I don’t know when I’ll be coming back here to talk to him or interview him again.

I’d like to start by asking you to tell me about this place, Haldenstein, where we are now and where you live and work.

At the beginning I lived in that old red building (he points out of the large window that faces onto the patio of the house, ed). My son lives there now. It was in 1971 that we bought a house here, with the engineer Jürg Buchli. Fully in keeping with the ideals of sixty-eight, we renovated that building ourselves. Many years have gone by and I’ve constructed two more buildings here to live and work in. All in a very natural way, without planning.

The first wooden studio-house was built in 1985.

The idea of that building was to have a room on the upper floor for designing and working and to keep the room underneath, at the level of the garden, for the family, but in fact I’ve never used it like that, as a gartensaal, I mean. In the red house we had no space for a garden and I thought of designing the architecture in that way. Then seven or eight years ago my studio had grown and I had the chance to buy the piece of land nearby. I waited for the bank to let me have the funds, and when they came this other building was born. With the passing of time I started to feel at home here. Perhaps not so much in the first ten years, but afterward yes. Now I think that this place has a really great quality. Because in this small and pleasant corner among the Alps, all the houses belong to us or to friends. And this gives us the possibility of maintaining the quality of the place. It’s a little bit of paradise here. But perhaps the crucial thing to be said about this place is that living and working coincide here, there’s no difference. The image in a way is that of the farmer with a large working family, children, grandchildren and so on. This has always been the way I work.

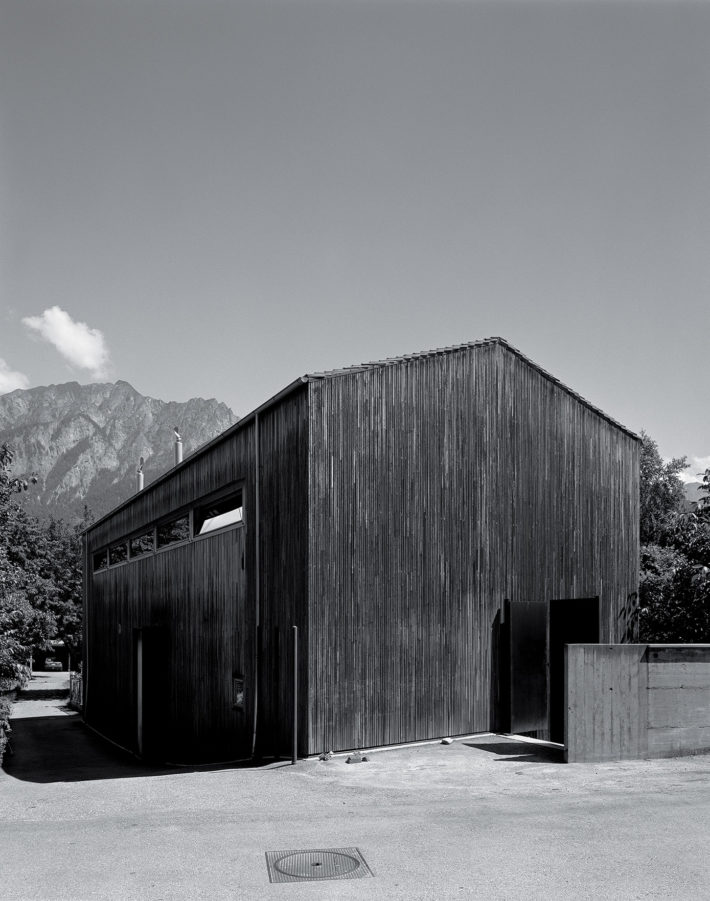

Zumthor Studio, Haldenstein, 1986. Photo: Hélène Binet.

Here there is a strange sense of the passing of time. Everyone who spends even just a day at your studio notices it. The atmosphere here seems suspended, but very dense. And this kind of relationship with time is at bottom part of your practice.

I believe I am capable of creating an atmosphere. Yes, the time here is dense, characterized by concentration and intensity in the work. At the moment there’s a very fine group of twenty, twenty-five people who are working with me and it’s fantastic. It’s not a family, but a genuine community for doing something with passion. And it’s as if by being together we grow stronger, as if everyone sprouted wings. Thomas Durisch who was one of my collaborators twenty years ago, once told me that for every architect in the studio doing things with me in a way gave strength to everyone. It was as if each of them thought while working together in the studio: “Yes, I could certainly do this too, indeed I could do it better.” Then when they went home some of them tried to do it by themselves, but realized that something didn’t work. It wasn’t the same thing. He said there’s a specific kind of atmosphere here, he called it fluidum. It’s like I’m curating this fluidum and the people somehow work in it. And now this atmosphere is very strong. It’s also nice that Annalisa (Zumthor’s wife, ed) is now working here. We are investing a little bit more in organizing things like table tennis and parties, between the studio and the house. People like to stay here and so do we. And this is very good for working. But you know, I want to say there’s a kind of mutual respect. It’s not about becoming friends, it’s about being good colleagues and working together.

I had the chance in the office to see you and your wife reviewing the projects together. It was interesting to see how you perfectly understood each other and how important it was for you to have feedback from a person close to you, but not an architect.

Now that Annalisa is here, I often go around in the office reviewing the projects with her. It’s very important to look at things with people who are not trained as architects, but who have good intuition and feeling. I mean Annalisa has been living with an architect for thirty five years, so she can read and judge a project. This is very important. As we know, in the end architecture is for normal people, not for specialists. Sometimes you become blind during the process. Days ago we were talking about the project of this house I’m designing for Tobey Maguire in Los Angeles. We were discussing the construction of a floor. I was totally convinced that the floor was not to be done in wood, because everything else was already wood. I thought of something mineral, a kind of stone, but she said “wood.” We put wood in the model and it worked incredibly. That was the most interesting proposition for the project, just to conceive that everything would be done in wood. Sometimes a view from the outside can sort a problem out.

Yes, I understand what you mean. Going back to the issue of time for a moment, in your house-studio you keep all the models, even those in one to one scale, of structural details, samples and materials. You said you like to live amongst them. How do you reconcile the idea of time you have with the idea of time your client might have?

Now this is not so difficult any more. It used to be difficult. Now clients like to get involved in a design process that can take years. People seem to understand… now that they know what I do. They understand that the time is needed. But you have to explain to them that this is not just technical work: arriving at good architectural concepts is artistic work in the end. If you have to write a symphony or a string quartet or… it’s like writing a book. It takes the time it needs, and that’s it. The architecture I do is not something you can order at the store. For me architecture is an authorial work. It’s not just rendering a service, it’s developing an idea with the client and becoming more intelligent together as the design process goes on.

You very often use samples on a one to one scale to check details, space and proportions. It’s something not so common in architectural practices in the world, because it takes a lot of time.

Le Corbusier worked in this way. People told me his studio in Paris was full of one to one things, handles, doors and so on. It’s the same kind of curiosity and passion for things to be just right in scale, material and proportions to the touch.

Zumthor House, Haldenstein, 2005. Photo: Pietro Savorelli.

You sometimes speak about memories and records as a part of the process of your inspiration. Can you tell me something more about it?

This is not a big mystery. We are all part of life and we absorb life. If we never had consciousness of what we experience and what we see, what we feel, we would not be human beings. This is the basic thing that we have. We have an experience. From there I decide. I don’t take a decision through abstract concepts. If there’s an abstract concept, I try to translate it immediately in my mind into a physical form so that I can somehow feel it with my body, soul and emotions somehow. The architecture I’m looking for doesn’t stay on paper as a concept. Therefore in my mind I always imagine my projects being part of the physical world.

You know, I thought immediately of you when I read The Museum of Innocence by Orhan Pamuk. The Turkish novelist collected thousand of objects and records in a room in Istanbul before starting to work on a novel set in the seventies, the time of his youth. He used all these objects as tools to write a story. He needed the real objects as an inspiration for him to start writing. Now if you go to Istanbul you can visit that room.

I like it. I’ll do a lecture now in Helsinki and afterward at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich with the title: Love at First Sight, and the subtitle will be About Spaces and Things. I’ll talk about specific objects and the space created for them. For instance my private collection of things that I keep on my shelves. Let’s say half the people have this passion for objects. Nice. Of course you can develop a passion for things and also for places. I have the feeling that this place here is full of passion. People may think this is a remote place, but actually it’s the center of my work. And geographically speaking I can reach the airport at Zurich in no time.

Working here I’ve never felt I was in a remote place. The architectural experience is unique of course, but it’s not just that. As you said it’s a mix of things: the place, but mostly the community of people. This makes the experience here stronger. It makes this place a sort of “right” place. And there’s another point. It was here that I met Richard Serra, the kind of person you maybe meet once in your life. Or Maurizio Cattelan. And the director Wim Wenders was here. This place, now that you’re here, has a catalyzing power. It can make us think about the notion of “center” in our contemporary society, or the new idea of geography you were referring to before. What is your relationship with other world-famous architects?

Respect from a distance. The opinion of architects who don’t belong to the team working here would somehow disturb the work. Their opinion would bring a wrong kind of energy. The construction of a specific concept and emotion for a project developed here together over hundreds, maybe thousands of hours cannot be shared easily. Even good or intelligent critics would seem like an intrusion.

Here you’re not disturbed by anything and are completely into the work, only focused on that.

Yes, all the time. And if there’s something that can disturb this I have to eliminate it. You know I can be pretty hard and say: “Ok that’s it, out please.” Because I need fire here and it has to be my fire.

In this connection, can I ask you something about the relations you have with the media? What do you think of the image of your work presented to the world?

It’s difficult. I’m still reluctant, but I’m trying to put it in a more polite form compared to twenty years ago. I could say that I’m more polite now! But it’s more like I’m trying to protect my work here. I’m happy that people can appreciate my work, that people can see it and so on. I’m trying to show and explain my practice and myself to the outside world, and make myself understood. For this reason I have started to go out again, giving a lecture every once in a while. I go to the ETH in Zurich every three years or so to give a lecture and to talk so that the students can see how I work, my interests and passions, and my joy. This is all I want to convey to the outside. In the last years we have started working on making a homepage for this office on the web. Probably it’s going to be a one-page website, with no images, and with only a text explaining the office philosophy: what we do and what we don’t want to do. Information about shows and books and publications, of course. It’s the same thing again: I don’t want to be snobbish by not having a page. We’ll do something simple, not advertising ourselves.

Peter Zumthor, Sogn Benedetg Chapel, Sumvitg, 1988. Photo: Hélène Binet.

Talking about distributing and disseminating thoughts about architecture, you’ve been a teacher. What kind of suggestion would you give to a student, to a young architect?

If you start to become an architect you should somehow start to build up your personality. You should ask yourself questions like: Who am I? What do I have inside me? What do I like? Why do I like this? When teaching you should encourage people to come up with this attitude. You really have to be careful not to suffocate them with many big theories. I think it could be very dangerous to start your education in architecture in an abstract way. You have to create a good atmosphere so that people can express themselves. Not impress anybody. And there are other important things to learn which really could be taught and in my opinion are not taught enough. This is a discipline too. It’s a mestiere, the craft of making. You should take it seriously. Light is light, shadow is shadow and there’s construction. Architects should learn everything about construction!

How did you learn things?

It’s a good question. One could say I’m an autodidact, but I think I’m the opposite! I grew up in a family where everything was made by hand. “The craft of making” again. So in my house this was a sort of tradition. We were doing everything by ourselves. I learned in a really technical way, my father was a cabinetmaker. I had to work in my father’s shop, I didn’t want to do that, but he forced me to do it so that I could walk in his footsteps. That was a very powerful experience. I had to stay there eight hours a day, sometimes doing very repetitive and boring work. In this way I learnt how to aim at quality and precision in my work with endurance and persistence. Then I went to the Kunstgewerbeschule in Basel, the Academy of Applied Arts, and there the school was organized on the lines of the Bauhaus: a one-year course, Vorkurs, of preparation teaching the basics of design, and the Fachklasse, teaching knowledge of a specific field. In my case this was furniture and interior design. I didn’t know it at the time, but looking back I saw that everything I learned there I learned in the first year, during the basic course. Not during the Fachklasse. In the Vorkurs I learnt about the principles of composition with lines, areas and volumes, the principles of writing and typography, the techniques for recognizing and mixing colors. Then drawing objects, animals, plants, human beings by hand, and this practice was mainly about looking precisely. All drawing is about looking… You start to draw cubes there for instance. Yes, drawing cubes. If I remember well it was twelve hours a week of drawing cubes. For the first half year, only drawing cubes.

Really?

Yes. You have the cube on the stand in front of you, you have to draw it and then the teacher sits down and places his eyes where your eyes were and looks at your work, maybe saying: “Are you looking at this cube from a helicopter or what? I don’t see this cube like this. Start again.” Then the same thing with writing. We had to learn handwriting, with a big pen, Carolingian script. My teacher studied it at the Bauhaus itself. Here everything was about negative and positive space. Everything done by hand. The first day of the Vorkurs I remember the professor came in saying: “Hey guys, this school is called Kunstgewerbeschule, but what you are doing from now for a year has nothing to do with Kunst (art, ed). Just so that you know.” And he was right in a way, it was mestiere. These were my two basic trainings, and then in 1967 came a sort of ethnological education in art history for me: ten years at the Department for the Preservation of Monuments in the Canton of Graubünden. Looking at farmhouses, looking at settlements. I wrote a couple of books on this topic. I was doing inventories, studying the structures of historical settlements and checking historical art forms inside buildings: for instance the decoration on the façade of farmhouses, like graffiti in the Engadine. It was a way to learn art history from the bottom up. I was studying vernacular architecture. It was a fantastic and formative experience. Before that I had also studied at the Pratt Institute in New York, and there I really learned nothing. I went to the industrial design class and the teacher looked at the material I had done before and told me: “I cannot teach you anything, none of my students can do what you have already done.” But one good thing was that I met there Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, László’s wife. She was teaching the History of Architecture at the Pratt and I wrote two papers for her course. She was an eyewitness to European architecture, I remember she often talked about all these people like Mies van der Rohe, who had been her friend.

Peter Zumthor, Memorial to the Burning of Witches, Vardø, 2007-ongoing (model). Photo: Jiri Havran.

How do you view your early projects now, looking back? How has the way you design changed over the years?

The method has become much better. I teach the people working with me, and I think that now it’s functioning very well. We do things and then we talk about them. We do and we talk all the time. The process is very model-related, its core is image-related and I’m the director of it all. As you know, I gather everybody in the office in front of the project and I make up the questions. I put the questions in the right order and I wait for a reaction. When somebody wants to explain his answer I always say: “Please, no. Just say if you like this solution or that solution.” If you start to rationalize you cover up the immediate reaction, your immediate feeling. It’s more like keeping this fluidum of immediate reaction to things. I really don’t want to kill off this first reaction by talking about it too early. And most of all I think that every emotional reaction is true for the person feeling it. It cannot be argued by another person.. I think this procedure is pretty perfect for me. The most difficult thing for me is that I’m impatient. My wife is helping me to be patient with my architects, I think I’m getting a bit better now. In the last few years I’ve been trying to improve my understanding of individual people, of what a person is able to do and what not. Before I was probably a bit too schematic in thinking that everybody should be able to do everything, which is completely stupid. Somehow a while ago I was taking myself as a measure, a reference for my collaborators, expecting them to become like me. Referring to your questions about my old projects now, I can say that two days ago there was a concert in the Protective Housing for Roman Archaeological Excavations in Chur, a project I completed in 1986, and there I could see that certain details of the architecture were disturbing me. Small things, but I was really smiling when I looked at them. “These elements are too small,” I thought, or “these others should not be flush, they should stick out.” So in a way I could see that I have developed. Thirty years of always looking, checking, looking and looking again at details and proportions. Maybe I’ve become a little better than thirty years ago.

I remember one day we were talking in the office about a sample of zinc for a roof of the Almannajuvet Mine Museum project, in Norway. We were discussing the material and the roof structure, and suddenly you said something like: “It’s perfect for the floor!.” We looked each other in the office, surprised and not understanding what kind of floor you were referring to. You realized that instead of the poured lead, zinc would have been a perfect material for the floor of the Bruder Klaus Chapel, a project completed a couple of years before.

I’d forgotten this!

In a way it’s interesting to think of the possibility of making amendments to designs during the life of a building. Can I ask you now to talk a bit about some of your current projects? I’m referring for instance to the Memorial to the Witches Burned in the Finnmark, at Vardø in Norway. It’s a project you carried out with the artist Louise Bourgeois during the last period of her life. How was it working together?

We were invited to do a memorial building, she as an artist and me as an architect. I asked her to start, but she wanted me to start. So I designed my building, my interpretation of the task, and she took my design and reacted to it with her installation. So the memorial now consists of two buildings, a glass pavilion with a fire burning in it reflected by huge mirrors and my corridor building almost a hundred and twenty meters long. It’s a textile space with windows and bulbs lighting a biographical text on each of the ninety-one victims. The long textile space hangs in a wooden scaffolding. It’s a dark narrow passage. Two ramps as accesses on each side. Both buildings, the corridor and the pavilion, are situated exactly on the spots on the seashore where the women were burnt.

Can you tell me about some of your projects that you couldn’t build?

Projects are never in vain. Sometimes ideas never built come up again. It happens many times. I worked for three or four years to make something for a project called Poetic Landscape in the North of Germany. But it didn’t work and only later did I find out that the Bruder Klaus Chapel was the product of all the work I had done on the Poetic Landscape. Thomas Durisch is preparing a new monograph on my work and I’m sure it will be possible to see how ideas and projects that may have never been built or published reappear in other proposals.

It will be possible to find analogies between projects really distant in time. Looking back at the whole opus of an artist or an architect it’s nice to have the chance to see how all the ideas and themes explored can go together and can be summed up in a few strong and crucial concepts. But maybe it’s something that happens only with great artists and architects.

In my experience some things and concepts are basic. They always reoccur.

Zumthor House, Haldenstein, 2005. Photo: Pietro Savorelli.

Peter Zumthor, Zink-Mine-Museum Almannajuvet, Sauda, 2003-ongoing (model).

Peter Zumthor, Memorial to the Burning of Witches, Vardø, 2007-ongoing (model). Installation by Louise Bourgeois. Photo: Jiri Havran.