2 May 2017

Thirty years have gone by since he began his career as an architect at the Renzo Piano Building Workshop. Over these three decades Mario Cucinella, born in Palermo fifty-six years ago but raised in Piacenza and Genoa, has won many competitions and constructed many buildings, in Europe, North Africa, China and the Middle East. In Bologna, where he moved his studio from Paris in 1999, he now heads a staff of 60 architects, engineers and experts on sustainability. Social and environmental aspects occupy a central place in his designs, his university lectures and the work he does for the nonprofit organization Building Green Futures and for SOS | School of Sustainability—both of which he set up a few years ago. Cucinella is definitely on the ascendant. He has recently opened a branch of his practice in New York and his engagement book is full, but he has kept a low profile and doesn’t give himself the airs of a starchitect. With just a few days’ notice he made himself available for a meeting at the headquarters of Mario Cucinella Architects (MCA), which is located in an out-of-the-way alley not far from Bologna railroad station, in a large industrial space so nondescript that it almost passes unnoticed. He has an imposing build and a low and measured voice that he modulates with intensity, freely interweaving memories with stories of projects.

Let’s start by talking about the cities and the works of architecture that have left a mark on your life and your profession.

I was born in Palermo, but spent very little time there. We soon moved to Piacenza, where I went to a nursery school designed by Giuseppe Vaccaro, a Bolognese architect who was a leading figure in Italian modernism. Buildings don’t move, but they are able to travel in your memory: the structure of those spaces, the memory of those desks ranged behind a large expanse of glass through which a lot of sunlight always came in and of the garden surrounded by a low white wall was a source of inspiration for the kindergarten I built at Guastalla in 2015, a project which I’m very fond of. In buildings devoted to education, which are themselves a form of education, the responsibilities of the architect are greater.

Kindergarten at Guastalla, 2015. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects. Photo: Moreno Maggi.

When did you first think about becoming an architect?

At high school in Genoa, where I’d been living since I finished primary school. A cousin of my mother’s lived there who had a studio of architecture in the historic center: I was more fascinated by that place filled with drawings than by the workshop which belonged to my father, who was a craftsman. I enrolled in art school and then university where, in those days, there were two courses: figure painting and architecture.

What kind of training did you get from the University of Genoa?

It took a very pragmatic approach. There were good professors in the technical subjects and the scientific-mathematical grounding was very strong—the dean came from the world of engineering—but in composition my teachers were poor. Though I do remember with pleasure the lectures of Guido Campodonico. Then, in the final year, a teacher arrived who had the stature of a Mies van der Rohe: Giancarlo De Carlo. I studied with him up until my thesis.

What did De Carlo give you?

We didn’t have an easy relationship. His intellectual qualities were beyond dispute, but I struggled to understand and accept his particular way of practicing architecture. In him reason prevailed over instinct, and for me, given that I had a great desire to do things, and was driven by great passions, that characteristic of his was almost a limitation. It was not until later that I fully grasped the force of his visionary and poetic reflections, the value of his political and social engagement. The most important legacy that De Carlo has left us consists in having stressed the need to place ethical values alongside technical ones in the practice of architecture.

Expo Village, Cascina Merlata housing project, Milan, 2015. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects. Photo: Guido Maria Isolabella.

From De Carlo you passed to Piano. Another fine school.

In his studio there was a lively atmosphere and a great desire to do things. A lot of room was given to creativity and there were many stimulating projects to follow. I started with a summer job. I was highly motivated and it didn’t bother me if I spent my time molding polycarbonate or polystyrene: it was enough to be in that exciting environment. Then I began to work full time, intensely. After four years I was ready for a change, I wanted to go my own way. Genoa was a very fine city, but not an open one. I thought about moving to Paris and Renzo suggested I apply to Jean Nouvel, but I ended up in Piano’s studio on Rue Sainte-Croix-de-la-Bretonnerie.

Did you find what you were looking for in Paris?

It was a beautiful and stimulating city, a breath of fresh air after Genoa. It was there that I saw all the films of Pasolini and Fellini for the first time. But the experience at the Renzo Piano Building Workshop didn’t last long. The problem, with people who are great at what they do is that they get in your way. At a certain point you have to break away from them.

What was the trigger that made you take flight?

A series of lucky coincidences. I had won a competition held by the United Nations for the International Union of Architecture. I had prepared it in the evenings, after finishing my work in the studio. This was in the month of April in 1992. In Italy the Tangentopoli scandal had broken out, but in Paris the atmosphere was completely different: a lot of competitions had been announced for the area of the Grande Arche de la Défense. I had found out that one of the studios in Le Corbusier’s Maison Planeix in the 13th arrondissement was free, having been rented just for the time needed to work on one of those competitions. I had the keys after chatting for an hour with the owner, between cigarettes and drinks. At just that moment, Renzo decided to move his offices to Rue des Archives and to buy new furniture. He gave me his old stuff and offered me a consultancy contract for six months, to help me tackle the break from the economic viewpoint. I spent the first three years working on competitions on the first level of that studio and living on the second. Over time the office grew. We won two or three competitions and worked on projects in Italy too.

Then, in 1999, you moved the practice to Bologna. Why did you decide to come back to Italy?

I was tired of the demanding pace of a metropolis like Paris, of living in a beautiful condominium where I knew nobody. I landed up in Bologna on my way from Paris to the Marche, where I was overseeing the project for the new headquarters of iGuzzini. I liked its “medium” scale, finding it to be a city with great potential.

One Airport Square, Accra, Ghana, 2010-15. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects + Deweger Gruter Brown & Partners. Photo: Fernando Guerra.

In the years you’ve been working in Italy you’ve honed the aspects of design linked to sustainability, adopting specific practices applied to housing and city planning. Today many people are using the word “green,” perhaps in a superficial way. What are the requisites of a sustainable design?

If used improperly, the word quickly loses its meaning. Its real significance concerns the transition from the age of fossil fuels to the so-called post-carbon era. A necessary passage that stems from an awareness of the fact that the world in which we live needs to be taken care of. Imagining sustainable buildings means entering into a profound dialogue with the climate and with the location, utilizing little technology and working a great deal on form and on materials—materials that are playing an ever more active part in the attainment of the result, in that they are capable of doing an invisible job within a new circular economy. The way ahead is not an easy one, but there are no alternatives: there is no future without sustainability.

One of your most important projects from this perspective was the 100K House, but it was never built.

It guaranteed zero emissions of CO2 thanks to the integration of photovoltaic cells into the architecture and the adoption of a whole range of structural devices that made the apartment house a perfect bioclimatic machine. We tried to carry out this project first at Settimo Torinese, then in Lodi and finally in Calabria, hoping for the backing of municipal councils—it was a social housing project—but we have not got off the starting blocks, even though the 100K House is still germane and ready to go. I’m not giving up.

100K House, 2007-09. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects.

Social housing, a major theme of the 1970s, is still of great relevance. Do you think it could help us to overcome the crisis in the building industry?

When we launched the idea of the 100K House, in 2007, builders greeted it with great skepticism, afraid of the negative repercussions on their profits. The foundations of our work were technical and sociological: they were based on research carried out by the sociologist Mario Abis into the evolution of housing, conducted through an analysis of different social structures. The study identified eight typologies for the same number of lifestyles and dwellings. Social analysis of the market, which is not done either by building contractors or politicians, is an indispensable prerequisite for meeting real needs, and is undoubtedly a useful means of combating the crisis in the building industry.

How much does research count in your work?

It’s fundamental. I have a special team that focuses on environmental and climatic analysis. Research also helps me in my architectural and aesthetic choices, and reinforces my philosophy, which can be summed up by the concept of “creative empathy,” that is trying to understand a place in all its complexity and using creativity to shape the design. We also carry out investigations of specific themes that the studio wants to develop: the most recent was of a garbage dump in Tuscany and its impact on the surrounding area. An architectural practice is a cultural enterprise, it is not concerned solely with making a profit. Through research we anticipate the responses to possible demands.

COIMA Headquarters, Porta Nuova, Milan, 2013 – under construction. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects. Photo: Moreno Maggi.

The year 2017 sees you very busy in Italy, with construction underway at a series of sites and others about to get off the ground.

Yes. In Ferrara, ten years after winning the competition, we will be completing the new headquarters of the Regional Environmental Protection Agency in the city. Major projects are underway in Milan like the new offices of COIMA, which will be finished by the end of the summer, or the new IRCCS surgery and emergency center of San Raffaele Hospital and the 23-story UnipolSai Tower at Porta Nuova, where construction is about to start. We are also working for a private foundation on a building in Corso Venezia that will house the collection of Etruscan art of a Milanese family. And work has finally begun on the reclamation of the Falck area in Sesto San Giovanni, in part due to pressure from public opinion: it will be the site of the health and research center called the Città della Salute e della Ricerca. Work continues on the church of Santa Maria Goretti at Mormanno in Calabria, while it will be starting on the Arts and Sciences Center of the Fondazione Golinelli in Bologna. And I feel particularly strongly about the five interventions in Emilia that have come out of the Emilia Reconstruction Workshop, in which I was personally involved: they will bring back to life the same number of villages struck by the earthquake in 2012.

Milan is at the center of your activities. Do you think it is a city ready to accept your design philosophy?

The economic and political structure of Milan is creating the right conditions to embark on quality projects. There are people who are investing in the city, and for this reason a lot of interesting things, very different from one another, have happened and are happening. And the political world is an important agent in these changes. It is showing courage.

Speaking of investments and courage brings to mind the case of the much debated Stavros Niarchos Foundation in Athens designed by Renzo Piano, funded by the Greek shipowner and “gifted” to the city. Will it be good for the city and the country?

In Greece there is only one way out of the recession: to invest in culture. The country has no competitive infrastructure or industry, and lives on tourism: this is why enriching the range of culture on offer is a good choice. Think of Sydney and Jørn Utzon’s Opera House: it took 30 years to build it, but every year it generates two billion dollars’ worth of allied activities. Works of these dimensions are difficult to get going, but have an enormous potential.

On a small scale there are initiatives like Renzo Piano’s G124 project on the outskirts of our cities.

It is not very glamorous but highly effective work that has gradually begun to bear fruit. A good idea that has put the theme of the outskirts at the center of a forgotten debate and has triggered other actions, like the earmarking of 500 million euros by the government and the launch of programs of renewal by municipalities. I was very happy to have been able to work on the project for Catania. At the moment, my studio is collaborating on the Piano Casa Italia.

3M Italia Headquarters, Pioltello, Milan, 2010. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects. Photo: Daniele Domenicali.

The theme of reconstruction is a tragically topical one. What is the most correct way to intervene?

There are two ways: reconstructing after the earthquake and through prevention. It will require at least two generations to work on the existing heritage, developing a system of diagnostics that is able to deal with the structural problems of buildings. Restoring damaged buildings is also a way of getting new economies going. I believe that a serious policy of prevention ought to studying ways of providing incentives from this perspective, similar to the ecobonus [a system of tax credits designed to encourage energy efficiency]. We have everything we need to find out how to tackle the problem seriously. It will be our own fault if we do nothing.

Training is an important factor in looking to the future with intelligence. How does your SOS (School of Sustainability) work?

It is located on the upper floor of this building and is supervised by two young members of the studio’s staff. Going to conferences on the subject of sustainable architecture around the world, I sensed that there was a gap to be filled, a space neglected by the academic world and the professional one. So I came up with the idea of a place halfway between these two worlds, to be attended after graduation, for a year, where skills that have already been learned can be integrated with new work tools. We organize meetings with climatologists, journalists, librarians and sociologists, and we teach people how to use digital instruments and means of simulation. We organize occasions for the exchange of ideas with people who have different visions. All this work is geared toward a research project.

Mario Cucinella Architects, studio, Bologna. Photo: Giovanni De Sandre.

What projects have come out of the SOS?

Among other things, we have worked on a masterplan for the renewal of an area owned by the state to the west of the city of Bologna. Then on an initiative intended for India that we will present to the FAO: we have developed a “cold chain” to help small-scale family farms with less than two hectares of land to transport fruit and vegetables from the places of production to those of sale. We are transferring our knowledge to the school in order to shape an educational approach and provide the means needed for the training of a new professional figure.

All this in Bologna. But the MCA has now landed in New York too.

We are at the beginning of a wonderful story, I’m certain of it, even though at the moment we do not yet have any projects underway in that country. For that matter, I didn’t have any when I opened the studio in Paris either. It’s an investment that we will be making over the next ten years. I will spend part of my time in America. It’s important to live in places where the energy is high. In the United States there is a complicated market and a lot of conflict, because it’s a country made up of many different people, but there is a lot of faith too. It always takes a hint of recklessness to tackle new and unexpected things, but the unexpected is a fundamental component of creativity. If it doesn’t work, we will come home with a fine American experience and a bit more energy.

You’re arriving in the United States with Trump in charge, an emblem of the denial of global warming and other threats to the environment. This is certainly not a minor detail for an architect with your approach to design.

The position taken by Trump with respect to climate change may produce a strong reaction in defense of the environment. For this reason, it makes even more sense today to be playing an active part on the American scene.

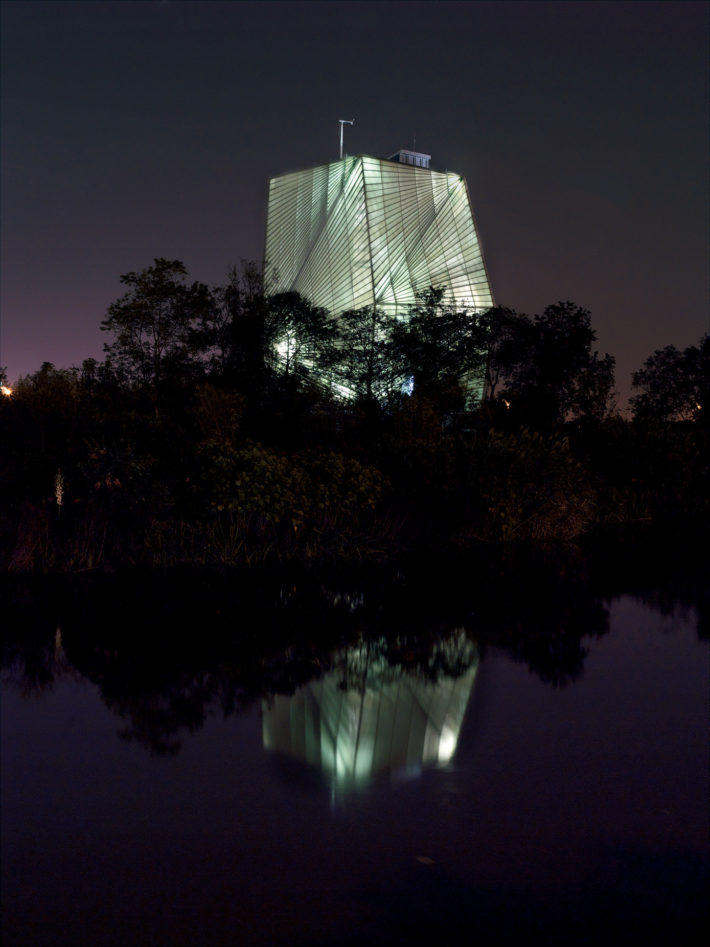

Kwame Nkrumah Presidential Library, Lake Volta, Ghana, 2013 – underway. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects.

New Rectorate of Rome University TRE, Rome, 2016 – underway. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects.

SIEEB, Sino-Italian Ecological and Energy Efficient Building, Beijing, China, 2006. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects. Photo: Daniele Domenicali.

Unipol Group Headquarters, Milan, 2015 – underway. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects.

CSET, Centre for Sustainable Energy Technologies, Ningbo, China, 2008. Design: Mario Cucinella Architects. Photo: Daniele Domenicali.