20 February 2018

“We’d had an argument, Ettore and I. I was in Milan, he was in Naples. He called me from a restaurant on Piazza Dante and serenaded me over the phone. At a certain point the song, Reginella it was, says: “Now we don’t love each other anymore.” I put the phone down. He had to choose that one? It was just because he didn’t know the words.”

Barbara Radice tells us who was, who is Ettore Sottsass, the companion of a lifetime. A hundred years after his birth, on September 14, 1917, and ten after his death, on December 31, 2007, exhibitions, books, interviews and companies have been paying tribute to the architect, the designer, the photographer, the writer, the intellectual. From Phaidon, which has come out with a new edition of its monograph, to Adelphi, which has brought out a collection of his largely unpublished writings, Per qualcuno può essere lo spazio, edited by Matteo Codignola. From the Triennale di Milano, which has celebrated him with the exhibition There is a Planet (until March 11, 2018), conceived by Barbara Radice and staged with the collaboration of Michele De Lucchi and Christoph Radl, to the Centro Studi e Archivio della Comunicazione of the University of Parma, which has put on Ettore Sottsass. Oltre il design, curated by Francesca Zanella, with over 700 pieces, including models, drawings and sketches.

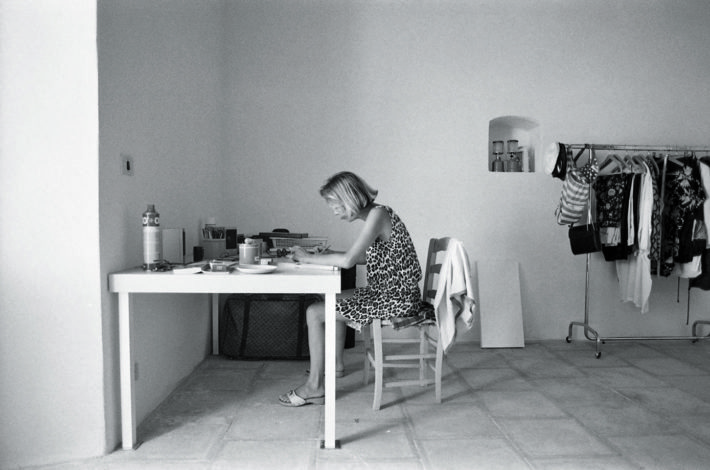

Barbara Radice, Filicudi, 1983. Photo: Ettore Sottsass.

What is left of that love?

Love doesn’t disappear, the body goes away and I greatly miss the flesh, but not the flesh in the sexual sense. I miss seeing him, touching him with my hands. His laugh, his eyes, everything that is physical, that we take in with our senses. His presence remains, mysteriously. There’s what you sense and still feel. And then his energy has left traces everywhere. It has been, is, very tough without him.

Thirty years of life together. You a young critic, with a degree in art history, daughter of the painter Mario Radice, grown up with an artist father. He an architect and designer of international repute, 30 years older than you. How did you meet, when did it all start?

In Vittorio Gregotti’s studio. Vittorio was a commissioner at the Venice Biennale and was interviewing me for a job. Sottsass happened to drop in. Then I saw him again on a vaporetto in Venice.

And when you met him at Gregotti’s what did you think of him?

Nothing: hello, how do you do? Zilch. When we saw each other again on the vaporetto, he sat down next to me and said: “I’d like to take you out for dinner.” This is a fine one, I thought. I didn’t even know whether I would go.

And how come you did decide to go?

I don’t know. I got off at the Giglio. He said: “I’m at the Monaco, I’ll be waiting for you.” And I went.

Barbara Radice and Ettore Sottsass, 1977. Selfie.

You recently published a book dedicated to Ettore entitled Perché morte non ci separi (“Why Death Doesn’t Separate Us,” Mondadori Electa). I’d like to quote to you from a poem by Franco Erminio: “The first time wasn’t when we took our clothes off, but a few days before, while you were talking under a tree. I felt far-off zones of my body coming home.” What did you feel when you fell in love?

It’s a beautiful poem. I don’t know when I fell in love. Ettore was in Venice for work and he was always inviting me to dinner. Afterward we used to go to Danieli’s to drink vodka and I thought he was just a lonely man. I was thirty years younger and he talked all the time about his wife and his lover. The last thing I imagined was that he was coming on to me. I thought he was attractive, likeable, charming and that he wanted company.

It didn’t even occur to you?

To me no. But one day my sister came to see me in Venice and I showed her a drawing by Ettore. It was of a person wearing a T-shirt with the name Barbara written on it who was diving into the lagoon from the window of Ca’ Giustinian, where I was working. I thought I was the person who was jumping into the sea. And my sister said: “Are you dumb or something? Can’t you see that it’s him, not you, and that he’s courting you? “The hell he’s courting me when he’s thirty years older than me, and has a wife and lover too,” I answered. One day he invited me to have dinner on Mont Blanc, another crazy idea. Then, at the end of the summer, I wrote something about a work of his entitled Metafore. Immediately afterward he called me and asked me to dinner. And there, in the end, I told myself that perhaps my sister was right.

Did you realize he was in love?

No, but I felt that he liked me. We went out for dinner in Milan and got drunk at Charlie Max, a club. He’d taken his shoes off to dance and the waiters brought him them back on a tray. Perhaps that was the moment we understood there was something between us: both of us were innocent or foolish, I don’t know which.

Barbara Radice and Ettore Sottsass, Milan, 1978. Selfie.

Or filled with wonder.

Or filled with wonder, and that’s how it went. There was a sense of belonging. The feeling of always being on the same side, looking in the same direction.

Had there been other love affairs before Sottsass?

Yes, but I’m not going to talk about them.

There’s something very striking that Ettore wrote about you in Scritto di notte. “Barbara’s body is beautiful, slim, a real animal body, firm, not at all athletic, but natural, perfect, feminine, with her sex set between her thighs like a precious stone. Her arms move in the air, it’s not clear why, perhaps to embrace the sky for the whole space of the horizon.”

He was kind.

In the last two years you have been working on curating the monographic exhibition at the Triennale called There is a Planet. There are nine rooms in all, in the spaces of the Galleria di Architettura. Do you have a favorite room?

I think I can say that they’re all favorites. Each has its own mood, its own character. For instance, I really like the room called “I’d Like to Know Why.” It has pieces of furniture made by the Gallery Mourmans in Lanaken, designed between 1997 and 2007, the last ten years of Ettore’s life. Very few people have seen them before.

Ettore Sottsass and Barbara Radice, Hammamat, 1977. Selfie.

Who worked with you on this exhibition?

Some dear friends. Christoph Radl wasn’t just responsible for the graphics, he did a lot more besides. And Michele De Lucchi took care of the whole structure, the completely dark ceiling, the recesses, the supports. Christoph had a brilliant grasp of the fundamental problem of the texts. He created the typeface, did the justification, a work of great complexity. This exhibition has been read a lot, not just viewed.

In what sense?

Literally. For example, the younger people were posting the writings on social networks the evening of the opening. I was moved. I was happy. At the root of the exhibition lay the decision that I ought to let him speak, because what he wrote is almost more important or as important as what he designed.

Do you go back and visit it from time to time?

Yes, I do. I myself continue to be amazed by this exhibition. Ettore wrote: “I’m interested in regaining an almost childlike sense of wonder. Recently I read some ancient Vedic texts in which you get a ‘pre-religious’ sense of the world and where the divine is an important part. We are in this divine space. Day and night we are astonished by what happens because we have no explanations. We open our eyes and pass through phenomena like children. I believe that if we could bring into play an attitude of this sort, a special patience, instead of always wanting to understand, possess and control, we might even be able to have another kind of industry.” This is the wonder I’m talking about.

Ettore Sottsass, Gatto rosa antico perplesso (Puzzled Dusky Pink Cat), 2006.

Sottsass was born in 1917, the year of the Russian Revolution. To mark the centenary Per qualcuno può essere lo spazio has been published too, in Adelphi’s Piccola Biblioteca series.

The publication comprises writings from the thirties, forties and fifties, and is the first in a series of volumes. In it there are some ideas so powerful that I included them in the exhibition. As in “Disegno magico” [Magic Design] or “Per un Bauhaus immaginista contro un Bauhaus immaginario” [For an Imaginist Bauhaus as Opposed to an Imaginary Bauhaus], an incredible text. It begins like this: “There is a magic ritual through which rain is invoked and propitiated by sprinkling the dry dust of the earth. In the same way the universe is invoked and propitiated by building a house. Architecture has always been a magic ritual, and is even more so today.”

A catalogue of the exhibition has been published too.

In the beginning we didn’t want to do it. Then, at the suggestion of Silvana Annicchiarico, director of the project, the idea was born of a simpler sort of notebook, printed on uncoated paper. The font was designed by Christoph on the basis of Ettore’s handwriting. We worked with Christoph for weeks on the sequence of the photographs and images. What emerges from the catalogue too is Ettore the writer, and very strongly.

The catalogue came out on the day the exhibition opened, September 14 last, his birthday. How did you use to celebrate it?

We drank a lot of wine. In his last years there was a friend who organized a wonderful party for him at his house in Antibes. Or, if we were away, we went out for dinner.

What could you give someone like Ettore?

Lots of things: books, cameras, sweaters, keyrings, records. He was really interested in music too.

What kind of music did he listen to?

All kinds. He loved classical music, world music, jazz, pop, rock, everything. Music was one of his great passions. When we were traveling around the world he used to buy records on stalls, in markets.

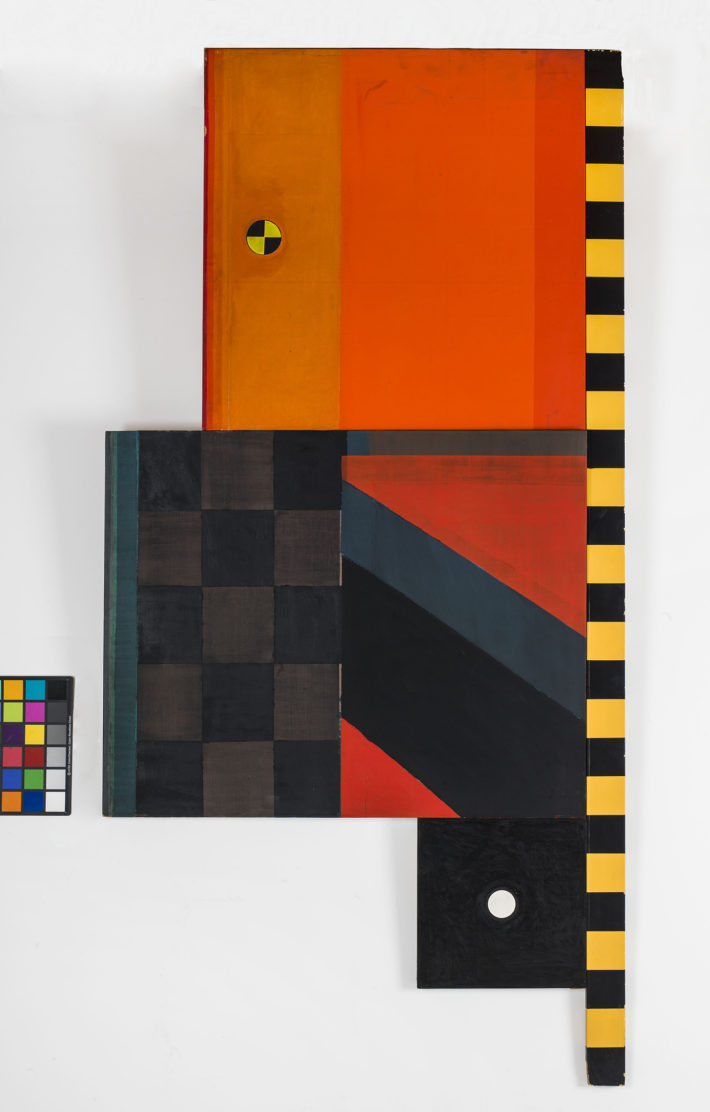

Ettore Sottsass, architectural design, 1988.

Was there anything you really couldn’t stand about him?

Ettore kept the volume very high. Well, if somebody plays Bach very loud in the morning when I’ve just woken up I become hysterical. We made an agreement: in the morning and after lunch, silence. Or we would talk. We talked about everything, food, philosophy, art, the soul, the hereafter.

Do you miss those talks today?

Ettore was no ordinary person to talk to. He was a very special companion.

When were the times you talked most?

After dinner or after we’d had a drink. Almost always the evening, because in the daytime he worked. Everywhere. We spent a lot of time together. One thing we always did was eat together, at midday and in the evening. I liked cooking for him. And without fail he thanked me for it.

It’s the feeling of taking care of someone.

I wasn’t just taking care, I enjoyed doing it. We passed our time like that.

What did you like cooking for Ettore? What were his favorite dishes?

I learned to cook from my Piedmontese mother, a very good cook, painstaking and precise. But what we liked above all, at that time, was spaghetti. I remember spaghetti Bandiera, a recipe taught to me by Amedeo of L’Aragosta, a restaurant on Ponza where I used to spend the summer: garlic, oil, chili pepper, cherry tomatoes and parsley. Perfect.

Ettore never cooked?

Once he made soup because I had a fever. It was revolting, a vegetable soup that resembled the swill you get in army canteens.

Did he smoke?

Well, he smoked a few joints of course. He liked to experiment with drugs. Once we were eating at the Torre di Pisa restaurant, in Milan. Elio Fiorucci came in and asked him if he wanted to try a pill. And what did that idiot do? He put it in his mouth and swallowed it. It was acid. He was out of it for a day and a half. I stayed by his side the whole time.

Ettore Sottsass, Wolf House, Colorado, 1986-89, with Johanna Grawunder, Sottsass Associati.

Did you talk about politics? What were his political ideas?

Ettore wasn’t a member of any party, he didn’t identify with an ideology. I too had been taught by my father to stay away from parties: “Use your own head, don’t listen to what others say,” he told me. Ettore was basically an anarchist.

He was thirty years older than you. Were they too many for you?

No, it was never a problem, he was a man of very great charm.

Did it make a stir in those days?

Those days? It’s not as if ten centuries have gone past. And then in the history of humanity, and we see it is still so today, the most powerful people are often accompanied by younger men and women.

Was he a teacher for you?

Yes, but I’ve always lived with artists and my attitude was not that of a devotee. Ettore didn’t put himself on a pedestal.

His photographs, also in the exhibition, show us Ettore the traveler.

We traveled mostly in Asia, in North Africa, in the Middle East. In the United States too, and Italy. We never went to sub-Saharan Africa. It was partly a question of money. For some journeys you needed a guide, and a driver. And then we liked to set off on our own.

Was he a good traveling companion?

When we first met, we went on a trip to Tunisia, down into the desert. The place where we stopped was very primitive. The first night we slept in a sort of cave. The dining table was dirty, so Ettore went to the bathroom and brought back a roll of mauve-colored toilet paper with which he covered the table. He used to do things like that.

Ettore Sottsass, Mobili Grigi, Poltronova, 1970.

What was never lacking at home?

Ettore often left drawings, notes, sheets of paper, lying around. So there were always pens and paints. He would even draw on paper napkins.

In those thirty years together did you ever leave one another?

We did separate for a certain period. But I don’t want to talk about it. It was a difficult moment, but it didn’t last.

Sottsass means “under the stone,” your surname is Radice, “root.” Did it ever bother you that everyone regarded you simply as Ettore Sottsass’s partner?

It didn’t bother me at all. I was his partner. I was and am very proud of him. And of being his partner.

Were you jealous?

Not much, but I should have been. He liked women a lot and admitted it too.

And of Fernanda Pivano?

No, she came before me. She was very sad about their breakup, she was Ettore’s age. It’s hard to compete with a woman who’s thirty years younger, you can’t do it. I was more jealous of the Catalan girl who he fell in love with after Fernanda and before me, because that had been a great passion.

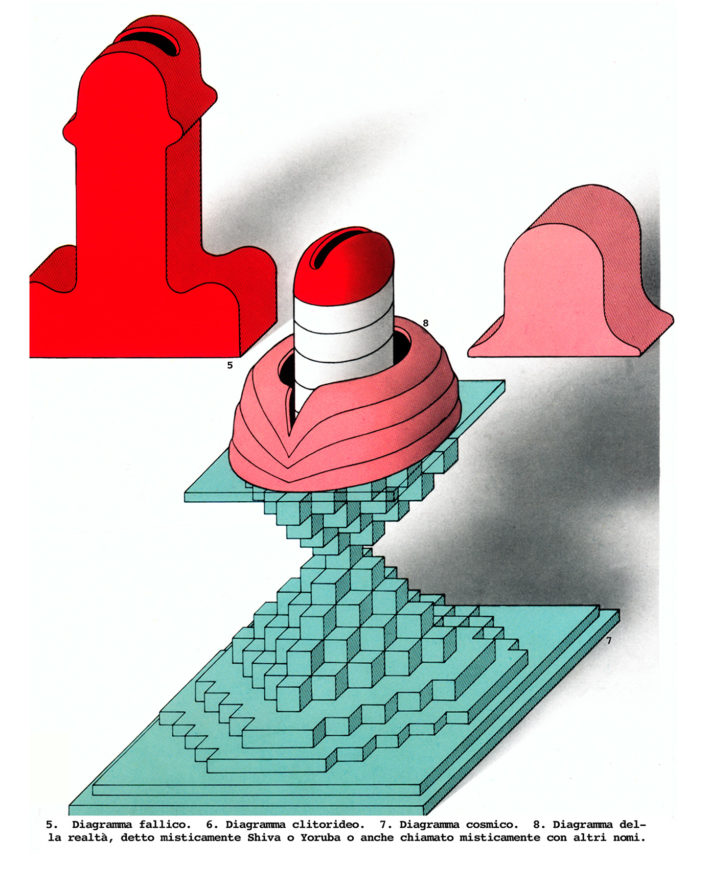

Ettore Sottsass, from In Magazine, 1971.

One of the various projects you worked on together was the presentation of Memphis.

The first exhibition was in 1981, with—more or less, they say—three thousand people at the opening. The whole of Corso Europa was blocked: a totally unexpected success. We couldn’t even get in and had to stand outside for at least an hour.

Why so many people?

You could feel that there was something in the air. Something was happening that would change design. There was a Tyrannosaurus rex on the invitation.

What was the idea at the root of Memphis?

Memphis had no philosophy, there were the objects. The point was that functionality could also be an emotional functionality and not just an ergonomic one.

How long did it take you to put the exhibition at the Triennale together?

Two years. It took me a year just to read all Ettore’s writings. After that, by dint of reading, looking and thinking I got the idea of the titles and of putting the writings on show as well. We were all very happy and excited about what was coming out. Silvana Annicchiarico and the whole staff were always in agreement too, they always gave us their support.

You can sense a lot of energy in There is a Planet. Do you think there are architects and designers today who have some of that cultural and intellectual vivacity?

In my life I’ve met cultured and fascinating men like Aldo Rossi, Arata Isozaki, Shiro Kuramata. But men like them or like Ettore are rare.

No one of the next generation? Fabio Novembre?

No, please. And I’m irritated with him over an interview he did with Ettore: aggressive and ill-mannered.

And how do you find rare men?

The other day there was a young woman at the exhibition, she must have been nineteen. She was studying in Venice. She asked me “Are you Barbara Radice? Can I have your autograph?” We started to chat and she ended: “Let’s hope one day I’ll meet someone on the vaporetto too, like you met Sottsass.” Of course, let’s hope. It’s a question of luck. Sometimes, you need to pray to the Unknown.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass. There is a Planet, La Triennale di Milano, curated by Barbara Radice, September 15, 2017 – March 11, 2018. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Ettore Sottsass, Barbaric Furniture, 1985.

Ettore Sottsass, Architetture Nere, 1991.

Ettore Sottsass, aluminum lamp, 1954.

Ettore Sottsass, Rocchetti, Manifattura Cav. G. Bitossi & Figli for the Galleria Il Sestante, 1957-1959.

Ettore Sottsass, Bandiera di morte 1 (Flag of Death 1), 1964.